A sense of having been wronged, together with a warped idea of political duty, brought Charles Julius Guiteau to the Baltimore and Potomac Station in Washington on July 2, 1881. On that same Saturday morning, President James Abram Garfield strode into the station to catch the 9:30 A.M. limited express, which was to take him to the commencement ceremonies of his alma mater, Williams College--and from there, Garfield planned to head off on a much-awaited vacation. He never made the 9:30. Within seconds of entering the station, Garfield was felled by two of Guiteau's bullets, the opening act in what would be a drama that included rising and then falling hopes for the President's recovery, the most celebrated insanity trial of the century and, finally, civil service reform that backers hoped might discourage future disappointed patronage seekers from taking revengeful actions.

Charles Guiteau's unhappy childhood began in Freeport, Illinois in September 1841. His mother, who suffered from psychosis, died shortly after Charles's seventh birthday. He was raised, for the most part, by his older sister, "Franky"--with some help from his stepmother following the remarriage of his father when Charles was twelve. He had speech difficulties and probably also suffered from what today would be called "attention deficit disorder." His brother recalled his father offering Charles a dime if he could keep his hands and feet still for five minutes; Charles was unable to collect on the offer.

Despite the personal obstacles Guiteau faced, he is described by Charles Rosenberg, author of The Trial of the Assassin Guiteau, as becoming "a moral and enterprising young man." At age 18, he would tell his sister in a letter that his goal was to work hard and educate himself "physically, intellectually, and morally." During a lonely year in college in Ann Arbor, Guiteau took comfort in the theological writings of John Noyes, founder of the utopian Oneida Community in upstate New York which practiced what Noyes called "Bible Communism." Charles left Ann Arbor in 1860 and headed east to Oneida.

After five years, Guiteau left the Community briefly to make a failed attempt at establishing the nation's first theocratic newspaper, the Daily Theocrat. He returned to Oneida for a year, spent twelve months back with family in Illinois, and then moved to New York City where a growing resentment of the Oneida Community would overtake him. Guiteau brought what can fairly be described as "a frivolous lawsuit" against the Community, demanding $9000 for his six years worth of work at Oneida. Noyes responded in affidavit by describing Guiteau in Oneida as "moody, self-conceited, unmanageable" and addicted to masturbation. Guiteau's attorney, soon realizing the case was a loser, dropped the cause, but Guiteau persisted in writing angry and threatening letters to the Community, blaming it for all of his personal problems, which included no family and no gainful employment. He sent letters to newspapers, the Attorney General in Washington, ministers, state officials, and everyone else he thought might aid in his professed goal of "wiping out" Oneida. In a letter to Charles's father, Luther Guiteau, John Noyes described Charles as "insane" and wrote that "I prayed for him last night as sincerely as I ever prayed for my own son, that is now in a Lunatic Asylum."

Charles withdrew again to Illinois, where for a few years he eked out an existence as a debt collection attorney and managed to find a wife, Annie Bunn, a local librarian. He proved soon to be an abusive husband, locking Annie in a closet for hours, hitting and kicking her, and dragging her around the house by her hair. "I am your master," Guiteau would yell, "submit yourself to me." The marriage ended after five years.

In the 1870s, Guiteau moved from place to place, from passion to passion. In 1872, while in New York collecting a bills from a few deadbeats to pay his own, he began to take an active interest in politics. His shady collection practices--including pocketing his commission without paying his client--landed him a short stay in a New York City jail. In 1875, he followed--until it died--a far-fetched dream of buying a small Chicago newspaper and turning it into an influential one by reprinting news from the New York Tribune, transmitted telegraphically to Chicago each day. When Charles's grand scheme collapsed, his father wrote of his son: "To my mind he is a fit subject for a lunatic asylum."

By the late 1870s, Guiteau's obsession had become theology and he became an itinerant lecturer, billing himself as "a lawyer and theologian" (and, on one handbill, as "The Little Giant of the West"). His lectures--composed naked, according to his own account--were incoherent ramblings on the imminent end of the world and Christ's reappearance in Jerusalem in 70 A.D.

In 1880, Guiteau adopted his final passion: politics. His cause became promoting the Stalwart faction of the Republican Party. In 1880, Republicans were split between the Stalwarts, who preferred to nominate Ulysses Grant for a third presidential term, and the Half-Breeds, reformers who favored the nomination of Maine Senator James G. Blaine. After delegates to the Republican convention in Chicago had cast 33 ballots, Grant led, but continued to fall just short of the majority needed for the nomination. On the 34th ballot, a move began for a darkhorse compromise candidate: James Garfield. By the 36th ballot, Garfield was the nominee. Having gotten most of his support from Half-Breeds, Garfield chose a Stalwart, Chester A. Arthur, as his running mate. Although Guiteau had written speeches in support of Grant, when Garfield became the nominee, Guiteau simply scratched Grant's name from his speech and substituted Garfield's.

Guiteau became a frequent visitor to the Republican Party's campaign headquarters in New York City. He sought speaking roles, but was rebuffed by campaign officials--except for one engagement in New York where he was authorized to speak to a small number of black voters. He reprinted his speech entitled "Garfield vs. Hancock" (Hancock was the Democratic nominee for president), a cliche-filled stream of over-the-top arguments, including his suggestion that the election of Hancock was likely to produce a second civil war. In November, Garfield narrowly defeated Hancock, and Guiteau concluded that the ideas presented in his speech secured the Republican victory. On New Year's Eve 1880, Guiteau wrote Garfield asking for a diplomatic appointment and wishing the President-Elect a happy new year.

After Garfield's inauguration in March 1881, Guiteau stepped up his campaign for a diplomatic post. He applied for posts as minister in Austria and consul general to Paris, and made the rounds between the White House and the State Department promoting his case. He bombarded Secretary of State James Blaine with letters, arguing it was his "rebel war claim idea" that "elected President Garfield" and that he deserved appointment as "a personal tribute" to his critical role in the recent campaign. He also wrote to Garfield, indicating in a May 10 letter: "I will see you about the Paris consulship tomorrow unless you happen to send in my name today." The Administration, unsurprising, grew tired of Guiteau's persistence. Secretary Blaine bluntly told Guiteau at the State Department on May 14: "Never bother me again about the Paris consulship so long as you live."

Guiteau, without family and nearly penniless, grew increasing isolated and depressed. Shortly after his confrontation with Blaine, Guiteau decided that Garfield needed to be "removed." In June, Guiteau concluded the mission to remove Garfield fell to him and was in fact a "divine pressure." On June 15, using fifteen borrowed dollars, he purchased a snub-nosed, forty-five caliber revolver. The next day he wrote an "Address to the American People," making the case for Garfield's assassination. In his address, Guiteau accused Garfield of "the basest ingratitude to the Stalwarts" and said the president was on a course to "wreck the once grand old Republican party." Assassination, Guiteau wrote, was "not murder; it is a political necessity." He concluded, "I leave my justification to God and the American people."

The Assassination

Guiteau learned from newspaper reports on June 30 that President Garfield would be catching a 9:30 A.M. train at the Baltimore and Potomac Station the following morning. He wrote a second justification for his planned assassination or, as he called it, "the President's tragic death." Guiteau, claiming himself to be "a Stalwart of the Stalwarts," wrote that "the President...will be happier in Paradise than here." He ended his note with the words "I am going to jail."

Guiteau arrived at the station about 8:30. He felt ready for the job, having practiced his marksmanship on a river bank on the way to his destination. Garfield entered the nearly empty station at 8:25 with Secretary Blaine and a bag-carrying servant. They had walked several steps into the carpeted "ladies' waiting room" when Guiteau fired his first shot. It grazed Garfield's arm. Guiteau moved two steps and fired a second shot. The bullet entered Garfield's back just above the waist. The president fell as the back of his gray summer suit filled with blood. As confusion erupted in the station, Guiteau tried to reassure onlookers: "It is all right, it is all right." The police officer on duty grabbed Guiteau.

A city health officer was the first doctor on the scene. Although he tried to reassure the president, Garfield said, "Doctor, I am a dead man." Garfield had been moved to the station's second floor when Dr. D. W. Bliss, who would be Garfield's head physician for the next eighty days, arrived. As Bliss and ten other doctors debated what to do next, a police ambulance arrived and--following Garfield's orders--transported the gravely wounded president to the White House and up to his bedroom.

In the hours after his arrest, Guiteau acted strangely. On the way to city jail with a police detective, Guiteau asked the officer if he was a Stalwart. When the detective replied that he was, Guiteau promised to make him chief of police. In jail, he balked at removing his shoes, complaining that if he walked barefoot over the jail's stone floors "I'll catch my death of cold." When a photographer snapped his photo he demanded a royalty payment of $25.

Although doctors initially assessed Garfield's chances as bleak--they expected him to die the evening of the shooting--after he survived the first forty-eight hours, they became more optimistic. By July 16, one of Garfield's doctors was quoted as saying the president's "ultimate recovery is beyond all reasonable doubt." A week later, however, Garfield's condition worsened. His conditioned then steadied, but he suffered from a severe cough, a low-grade fever, and was losing weight through much of August. On September 6, Garfield was taken by a special train almost to the door of his summer seaside cottage in New Jersey where, it was hoped, the ocean breezes might help his deteriorating condition. They didn't. On September 19, at 10:35 P.M., the president died. An autopsy identified the cause of death as a rupturing of an aneurysm in the splenic artery.

Events Leading to the Trial

In the weeks following Garfield's shooting, Guiteau seemed to enjoy his new found notoriety. He sent a letter to "the Chicago Press" announcing his intention to write and publish and autobiography entitled "The Life and Theology of Charles Guiteau." He expected to make bail and head out on the lecture circuit to speak on matters ranging from religion and politics--and he expected the fees for his lectures to pay for the first-rate lawyers that would surely win his acquittal.

As the summer progressed, Guiteau became more agitated. He was upset with prison officials for denying him access to newspapers and keeping him in near isolation. When word came in September that the president had died, Guiteau fell to his knees.

Guiteau rebounded quickly, however. The day after Garfield died, he penned a letter to the new president, Chester Arthur. "I presume you appreciate [my act]," Guiteau wrote, noting that "It raises you from $8,000 to $50,000 a year" and from "a political cypher to President of the United States with all its powers and honors." He described his victim as "a good man but a weak politician." Guiteau's spirits seem to rise further with the publication of the autobiography he had written in prison. The autobiography, published in the New York Herald, included his personal note that he was "looking for a wife" and his hope that applicants for the job might include "an elegant Christian lady of wealth, under thirty, belonging to a first-class family."

Needless to say, the public included far more Guiteau haters that Guiteau fans. Concern about lynching led officials to move Guiteau to a brick cell with only a small opening at the top of a bulletproof oaken door. His biggest threat, it turned out, was not from the public, but from prison guards. On September 11, 1881, a guard named William Mason fired at Guiteau, but missed. (The public responded with donations to Mason and his family, but the trigger-happy guard still was court-martialed and received an eight-year term.)

George Corkhill, the district attorney for Washington, understood that Guiteau was likely to raise an insanity defense. Guiteau's speeches, statements, and letters were more than passing strange--and assassination almost seems by its very nature to be the product of a diseased mind. Corkhill's early statements on the issue were dismissive of Guiteau's potential insanity claim. "He's no more insane than I am," Corkhill told a reporter on July 9. In Corkhill's view, Guiteau was a "deadbeat" who "wanted excitement" and now "he's got it."

Formal proceedings against Guiteau began in October. On October 8, Corkhill filed the presentment and indictment against the prisoner for the murder of James Garfield. Six days later, Guiteau was arraigned. George Scoville, Guiteau's brother-in-law, appeared and asked the court for a continuance to gather witnesses for the defense. He told Judge Walter Cox that the defense intended to make two primary arguments: that Guiteau was legally insane and that the president's death resulted from medical malpractice, not Guiteau's shooting. Judge Cox granted the defense motion and set the trial for November.

Guiteau, unsurprisingly, considered himself supremely qualified to head his own defense. He drew a sharp distinction between "legal insanity," which he was willing to claim, and "actual insanity," which he thought a detestable insult. He was sharply critical, for example, of Scoville's questions concerning whether any of his relatives had spent time in lunatic asylums: "If you waste time on such things, you will never clear me." Instead, in Guiteau's view, he was legally insane because the Lord had temporarily removed his free will and assigned him the task he could not refuse. In addition to insanity, Guiteau proposed to argue that the doctor's clumsy treatment attempts were the true cause of Garfield's death and, moreover, the court in Washington lacked jurisdiction to try him for murder because Garfield died at his seaside New Jersey home.

Scolville's legal conclusions differed from those of his client on both the issue of causation and jurisdiction. He decided to drop both arguments and concentrate on insanity. Both Scoville and attorneys for the government began scouring the country for medical witnesses best able to address the issue of the assassin's mental state. Corkhill landed Dr. John Gray, the superintendent of New York's Utica Asylum, as the prosecution's chief adviser on insanity issues. After interviewing Guiteau, Gray wrote in a memo to Corkhill that Guiteau acted out of "wounded vanity and disappointment," not insanity.

Gaining an acquittal by reason of insanity in 1881 was no easy task. Under the prevailing test, the so-called M'Naghten rule, the government need only show that the defendant understood the consequences and the unlawfulness of his conduct. This test, for Guiteau, posed nearly insurmountable obstacles. Guiteau knew that it was illegal to shoot the president. He knew that if he pulled out his revolver and shot and hit the president, that the president might die. Moreover, Guiteau did not act impulsively, but planned the assassination and waited for a good opportunity. Under the conventional interpretation of M'Naghten, Guiteau was a dead man.

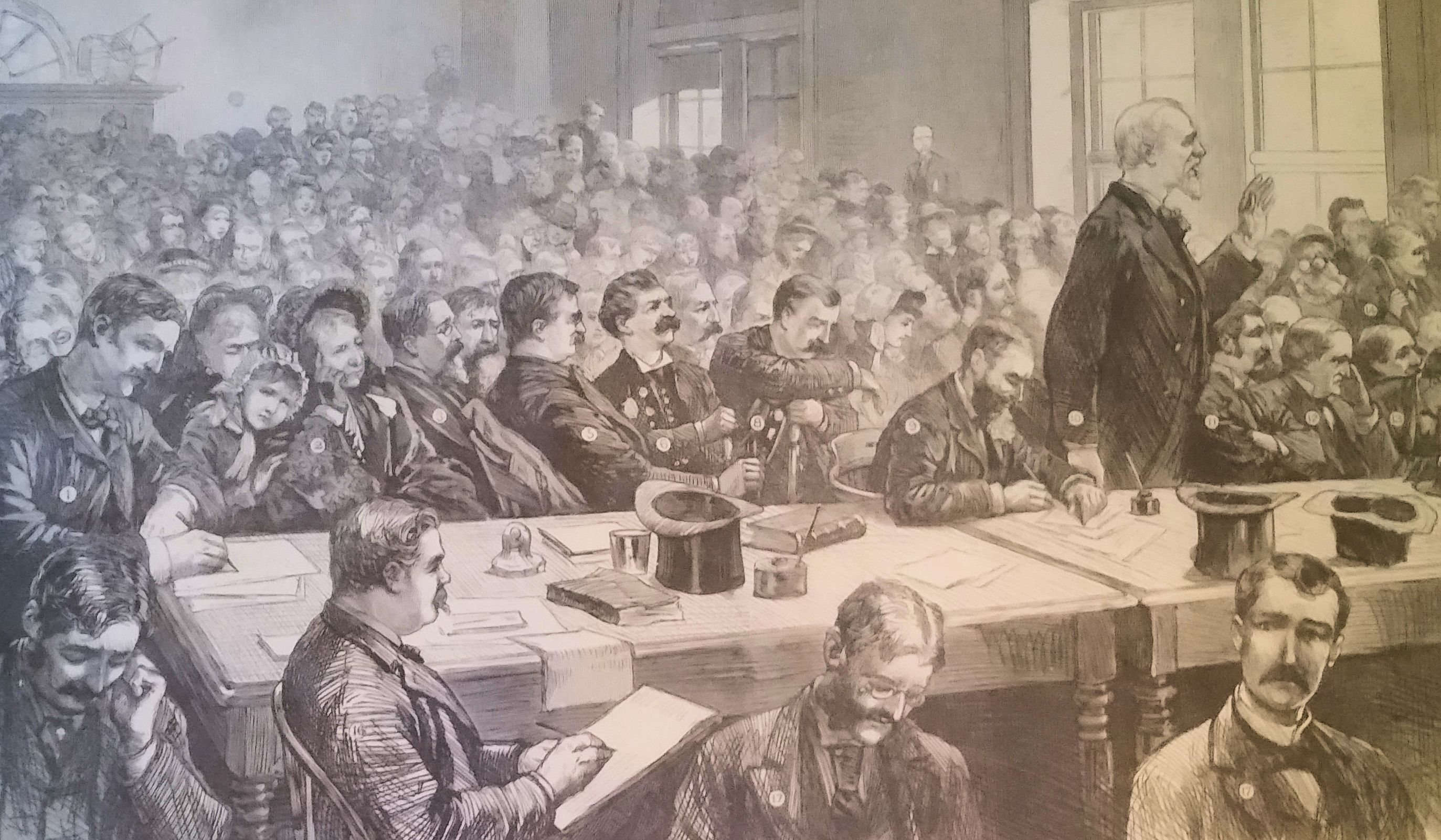

The Trial

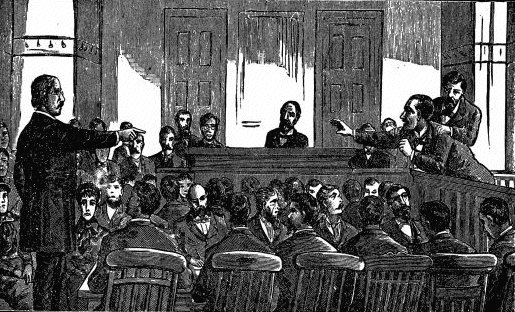

The trial of Charles Guiteau opened on November 14, 1881 in a packed courtroom in Washington's old criminal court building. Guiteau, dressed in a black suit and white shirt, asked the proceedings be deliberate so not to offend "the Deity whose servant I was when I sought to remove the late President." Jury selection proved difficult. Many potential jurors claimed that their opinions as to Guiteau's guilt were fixed. "He ought to be hung or burnt," one panel member said, adding, "I don't think there is any evidence in the United States to convince me any other way." It took three days, and the questioning of 175 potential jurors, to finally settle on a jury of twelve men--including, against the wishes of Guiteau, one African-American.

As the prosecution was set to begin its case, Guiteau jumped up to announce that he was none too happy about his team of "blunderbuss lawyers" and that he planned to handle much of the defense himself. "I came in here in the capacity as an agent of the Deity in this matter, and I am going to assert my right in this case," he said.

The prosecution focused its early efforts in the trial on detailing the events surrounding Garfield's assassination. Witnesses included Secretary of State Blaine, Patrick Kearney (the arresting officer), and Dr. D. W. Bliss, who performed the autopsy. Letters written by Garfield shortly before the assassination were introduced as exhibits, as were several of the vertebrae shattered by Guiteau's bullet.

The most important testimony came from Dr. Bliss. Spectators cried and cringed as Bliss made his point, using Garfield's actual spine, that the shot fired by Guiteau directly caused the President's death, however long it took to do so. As Guiteau was driven away from the courtroom after Bliss's testimony, a horse pulled alongside his van and the horse's drunk rider--a farmer named Bill Jones--fired a pistol through the bars of the van. The bullet struck Guiteau's coat, but left the prisoner uninjured.

In his opening statement for the defense, George Scoville told jurors that as society has gained more knowledge of insanity it has come to recognize that persons so afflicted deserve sympathy and treatment, not punishment. This trend, he said, is part of becoming a civilized people: "It is a change all the while progressing to a better state of things, to higher intelligence, to better judgment." He argued that the jury should try to determine, based on expert testimony, whether Guiteau's actions were the product of a deranged mind. Guiteau, meanwhile, offered untimely interjections. When Scoville said Guiteau's "want of mental capacity is manifest" in his business dealings, the prisoner rose to his feet and insisted, "I had brains enough but I had theology on my mind." At times, according to newspaper accounts, Guiteau was "foaming at the mouth" as he shouted his objections to Scoville's characterizations of his odd legal practice.

Defense witnesses painted the picture of a strange and disturbed man. A physician summoned to Guiteau's home after he threatened his wife was an ask testified that he had told Guiteau's sister at the time that his brother was insane and should be committed. He concluded Guiteau had been captured by "an intense pseudo-religious feeling." A Chicago attorney who visited Guiteau shortly after the assassination told how Guiteau, in a voice that veered from a whisper to a shout, claimed that the shooting of Garfield was the Lord's work and he merely carried it out. Other witnesses pointed to the strange behavior of Guiteau's father as evidence that the defendant's insanity might be a hereditary condition. They told of Luther Guiteau's attempts at faith healing and his belief that some men could live forever.

Charles Guiteau took the stand on November 28. Responding to his attorney's questions in a hurried and nervous style, Guiteau traced for jurors the story of his life. Much of the testimony focused on his years at the Oneida Community--the community Guiteau grew to hate and sought to destroy. He also described in great detail his political activities and inclinations during the spring of 1881, finally turning to the prayerful period of June when he awaited word from God as to whether his inspiration to kill Garfield was divine. He took some of his own narrow escapes from death (a ship collision at sea, a jump from a speeding train, three attempted shootings) as evidence that God had an important plan for him. He insisted that he had performed a valuable service in killing Garfield: "Some of these days instead of saying 'Guiteau the assassin', they will say 'Guiteau the patriot'."

On cross-examination, prosecutor John K. Porter tried to suggest to jurors that what the defense claimed was evidence of insanity was instead only evidence of sin. He forced Guiteau to concede that he thought the assassination would increase sales of his autobiography. He demanded to know whether Guiteau was familiar with the Biblical commandment, "Thou shalt not kill." Guiteau responded that in this case "the divine authority overcame the written law." He insisted, "I am a man of destiny as much as the Savior, or Paul, or Martin Luther."

The heart of the defense case was built by medical experts. Dr. James Kienarn, a Chicago neurologist, testified that a man could be insane without suffering from delusions or hallucinations. He offered his expert opinion--accepting as true a long list of assertions about Guiteau and his state of mind--that the defendant was doubtless insane. (Kiernan's credibility, however, was badly damaged in cross-examination when he guessed one out of every five adults was--or would become--insane.) Seven additional medical experts for the defense followed Kiernan to the stand, but seemed--to most observers--to add little new support for the insanity claim.

Few experts had been as adamant about Guiteau's insanity as New York neurologist Dr. Edward C. Spitzka. He had written that it was as plain as day that "Guiteau is not only now insane, but that he was never anything else." It is no wonder that Scoville depended heavily on Spitzka's testimony. On the stand, Spitzka told jurors that he had "no doubt" that Guiteau was both insane and "a moral monstrosity." The doctor drew his conclusions as much from his looks (including his lopsided smile) as his statements, concluding that the defendant had "the insane manner" he had so often observed in asylums. He added, based on his interview with the prisoner, that Guiteau was a "morbid egotist" who misinterpreted and overly personalized the real events of life. He thought the condition to be the result of "a congenital malformation of the brain." On cross-examination, prosecutor Walter Davidge forced Spitzka to admit that his training was as a veterinary surgeon, not a neurologist. Conceding the point, Spitzka said sarcastically: "In the sense that I treat asses who ask me stupid questions, I am."

The prosecution countered with its own medical experts. Dr. Fordyce Barker testified that "there was no such disease in science as hereditary insanity." Irresistible impulses, the doctor testified, were not a manifestation of insanity, but rather "a vice." Prison physician Dr. Noble Young testified that Guiteau was "perfectly sane" and "as bright and intelligent a man as you will ever see in a summer's day." Psychiatrist (called an "alienist" at the time) Allen Hamilton told jurors that the defendant was "sane, though eccentric" and "knew the difference between right and wrong."

Dr. John Gray, superintendent of New York's Utica Asylum and editor of the American Journal of Insanity, took the stand as the prosecution's final--and star--witness. Gray, based on two full days of interviews with Guiteau, testified that the defendant was seriously "depraved," but not insane. Insanity, he said, is a "disease" (typically associated with cerebral lesions, in his opinion) that shows itself in more than bad acts. Guiteau displayed far too much rationality and planning to be truly insane, Gray concluded.

Closing arguments began on January 12, 1882. Prosecutor Davidge emphasized the legal test for insanity, which he claimed Guiteau failed to meet. Guiteau, Davidge argued, knew that it was wrong to shoot the President--and yet he did. He warned the jury not to reach a result that would be "tantamount to inviting every crack-brained, ill-balanced man, with or without a motive, to resort to the knife or to the pistol." Judge Porter, in the government's final argument, predicted that Guiteau will soon feel for the first time real "divine pressure, and in the form of the hangman's rope." For the defense, Charles Reed argued that common sense alone--the facts of his life, his vacant glance--should persuade jurors of Guiteau's insanity. He told jurors that if it were up to Christ, he would heal and not punish such an obviously disturbed man as his client. Scoville, in a closing argument that lasted five days, suggested that Guiteau's writings could not be the product of a sane mind and that the defendant was owed the benefit of doubt. He scoffed at the prosecution's suggestion that only a cerebral lesion could prove a man insane: "Those experts hang a man and examine his brain afterward."

Guiteau offered his own closing. At first, Judge Cox denied his request. Disappointed, Guiteau said that the judge had denied the jurors "an oration like Cicero's" that would have gone "thundering down the ages." Later, when the prosecution (fearing adding a possible point of error to the record) withdrew its objection to Guiteau's request, Judge Cox reversed his decision. Guiteau looked skyward and swayed periodically during his address, which included the singing of "John Brown's Body" and featured comparison's between his own life as "a patriot" and other patriots such as George Washington and Ulysses S. Grant. He insisted that the shooting of Garfield was divinely inspired and that "the Deity allowed the doctors to finish my work gradually, because He wanted to prepare the people for the change." He warned the jury that if they convicted him, "the nation will pay for it as sure as you are alive."

The jury deliberated for only an hour. In a candlelit courtroom, jury foreman John P. Hamlin announced the verdict: "Guilty as indicted, sir." Applause filled the room. Guiteau remained oddly silent.

The Sentence and Aftermath

Judge Cox sentenced Guiteau "to be hanged by the neck until you are dead" on June 30, 1882. Guiteau shouted at the judge, "I had rather stand where I am that where the jury does or where your Honor does."

On May 22, Guiteau's appeals were rejected. Guiteau still held out the hope that President Arthur, the benefactor--as he saw it--of his act, would grant a pardon. Arthur listened to arguments by defense experts for twenty minutes on June 22. Five days later, the President granted an interview with another defense partisan, John Wilson. Guiteau wrote a letter to Arthur asking that he at least stay the execution until the following January so that his case might "be heard by the Supreme Court in full bench." On June 24, President Arthur announced that he would not intervene. Hearing the news, an angry Guiteau shouted, "Arthur has sealed his own doom and the doom of this nation."

Guiteau approached his hanging with a sense of opportunity. He abandoned his plan to appear for the event dressed only in underwear (so as to remind spectators of Christ's execution) after being persuaded that the immodest garb might be seen as further evidence of his insanity. In the prison courtyard on June 30, 1882, Guiteau read fourteen verses of Matthew and a poem of his own that ended with the words, "Glory hallelujah! Glory hallelujah! I am with the Lord!" The trapdoor opened and Guiteau fell to his death. Outside the jail, a thousand spectators cheered the announcement of the assassin's demise.

In the years following Guiteau's execution, public opinion on the issue of his insanity shifted. More people--and almost all neurologists--came to the view that he was indeed suffering from a serious mental illness. Guiteau's case was seen in medical circles as supporting the theory that criminal tendencies were often the result of hereditary disease.