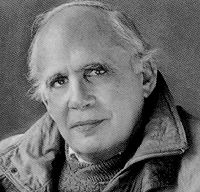

J. Anthony Lukas, two-time winner of Pulitzers, spent the last seven years of his life researching and writing his 754-page opus "Big Trouble," which will remain without question the seminal study of one of America's most facinating trials.

On the morning of June 5, 1997, Lukas met with his editor to discuss final revisions to Big Trouble. He returned in the afternoon to his Upper West Side apartment and hanged himself with a bathrobe sash. He was 64 when he died, ten years after being diagnosed with depression.

Lukas was known for the "excrutiating, almost obsessive precision of his research." After graduating from Harvard he worked as a reporter for the Baltimore Sun, then the New York Times. He won his first Pulitzer in 1967 for an account of a wealthy teenager found beaten to death in Greenwich Village by her counter-culture boyfriend. His second Pulitzer was for "Common Ground," a 1985 book about race relations in Boston. Lukas also wrote in 1971 a book about another famous trial, "The Barnyard Epithet and Other Obscenities: Notes on the Chicago Conspiracy Trial."

Many adjectives have been used to describe one of America's most brilliant writers: decent, erudite, insightful, dedicated, intense, energetic, inventive, sensitive, tender, self-righteous, brooding, restless. A friend described Lukas as "the happiest and the saddest man I know." Apart from his love of writing, Lukas found happiness in gardening, baseball, and pinball (Lukas bought his own machine: "The ball flies into the ellipse, into the playing field-- full of opportunities.")

"Big Trouble" was Lukas's first attempt at pure history, and the project left him full of self-doubt. He worried that his book was too ambitious, that he wouldn't be able to get his point across, that it didn't show his talents as well as "Common Ground." As the Big Trouble neared completion in the spring of 1997, friends worried that he seemed mentally and physically exhausted. On the Monday before he died, Lukas called an editor at Life who had assigned him the task of writing a piece on Caldwell, Idaho's changes since the Steunenberg assassination and told him "he didn't know what to write." Friends who knew Lukas said such a thing had never happened before.