Not even the wealthiest of Salem's residents were immune from accusations of witchcraft. Yet, as it turned out for Philip and Mary English, money had its advantages.

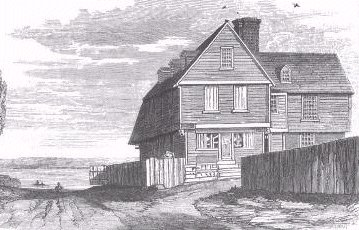

Philip English (born Philippe L'Anglois) emigrated to Salem in 1670 from the Isle of Jersey at age 19. Five years later, he married Mary Hollingsworth, the daughter of wealthy merchant William Hollingsworth and his wife, Eleanor. The couple established residence in a grand home with a view of the harbor. They raised two daughters in this beautifully proportioned home on Essex Street. Over the course of the next two decades, Philip English developed a highly profitable trading company and came to own a fleet of twenty-one ships, as well as fourteen lots and a wharf in Salem. English earned his money by trading fish for produce from the tropics and manufactured goods from Europe. Fishermen on ships owned by English sailed the North Atlantic coast from Maine to the Newfoundland Banks. English also took an active role in local affairs. In April 1692, he was elected a Salem Town selectman.

Troubles began just before midnight on Saturday, April 18, Sheriff George Corwin and his deputies, acting on an unknown accusation, arrived at the English home on Essex Street. Opening the curtains around Mary's bed, Corwin ordered her to accompany him. Not easily intimidated, Mary told Corwin to go away and arrest her in the morning. Corwin agreed to wait, ordering his deputies to guard the house during the night to prevent an escape. On Sunday morning, after Mary had eaten breakfast, she consented to be taken to a second-floor room at the Cat and Wheel tavern near the meetinghouse.

Mary English appeared before a large crowd at the Salem meeting house on April 22, 1692 to answer a complaint of witchcraft. The examination records for that day are lost, and so the precise reasons for the charge against her remain unknown. She most likely became a target because her husband attracted attention because he was a native French speaker (and the French, because of their association with warring Indians were anything but popular), because he was an Episcopalian in an overwhelmingly Puritan community, and because had unsuccessfully pursued contentious lawsuits over disputed property. It is also possible that general knowledge that Mary's dead mother had once been accused of witchcraft contributed to the accusation. Susannah Sheldon, who later accused Philip of witchcraft, claimed to have seen Mary's apparition, accompanied by a black man wearing a tall hat. Abigail Williams added to Mary's problems when she told authorities that George Jacob's specter told her that he had recruited Mary as a witch. Mary remained housed in Salem for three weeks following her examination. On May 12, she was transfered to a jail in Boston to await trial.

Philip's vocal criticism of his wife's arrest made himself an obvious target for a similar accusation. It came when Susannah Sheldon reported that English, at church service on Sunday, April 24, "stepped over his pew and pinched her," thus afflicting her "in a very sad manner." Later, Sheldon would tell authorities that English "brought his [the Devil's] book" and told her that if she didn't sign it "he would cut my throat." She added that a specter, telling her not to rest until she had told his tale, accused English of having "murdered him and drounded him in the sea." English warned her not to report the murder, Sheldon said. If she did so, he would "cut my legs off"and--for good measure--"kill the governor" and "ten folk in Boston" before six days passed. Sheldon accusations probably encouraged another witness, William Beale, to step forward with his own charges against English. Beale's dislike of English stemmed from being on the opposite side of a 1690 lawsuit over a claim to two tracts of land. Beale claimed that English had offered him a bribe in return for his favorable testimony in the case. Later, Beale said, when was discussing English's lawsuit with a friend, "my nose gushed out bleeding in a most extraordinary manner"--a nosebleed he attributed to English's witchcraft. Beale also speculated that the sudden deaths of two of his sons soon afterward might have been the evil work of English, in retaliation for his testimony against him.

On April 30, 1692, a warrant issued for English's arrest. Philip, however, knew in advance of the charge against him and, after first hiding in a secret room, fled to Boston, where he hoped his influence could be used to free Mary. When it became apparent that his absence was hurting--rather than helping--his wife he returned to Salem to face charges of witchcraft. Magistrates examined Philip on May 31, then ordered him sent to join his wife in a jail in Boston (a privilege granted through the help of English's friends). The Boston jailer freed the couple each morning, on the promise that they would return at night to sleep in the jail.

According to stories handed down in the English family, a Boston minister named Joshua Mooley convinced Philip and Mary to flee Boston just before the scheduled start of their witchcraft trials. Mooley based his Sunday sermon on Matthew 10:23, "If they persecute you in one city, flee to another." Just to make sure they got the message, Mooley later visited the couple in jail that evening, telling them that he had made arrangement for "their conveyance out of the Colony." Somewhat reluctantly, Mary and Philip took the advice, leaving behind their two teenage daughters to stay with friends in Boston while they made way by carriage for New York, where they intended to wait out the madness in Salem.

In New York, the Many and Philip English received periodic reports of the continuing hysteria in Salem. A combination of lost time in the fields and drought caused a food scarcity in Salem, and Philip arranged for a shipload of corn to be sent there to ease the suffering.

In 1693, with the hysteria finally ended, Philip and Mary returned to Salem to find that Sheriff Corwin had confiscated much of their property. The next year, shortly after giving birth to a son, Mary died. Philip returned to his shipping business. He also pursued claims for reimbursement of his property, finally getting 532 pound sterlings in 1711. He also is said (in some histories, although of doubtful veracity) to have found a more personal type of revenge: stealing Corwin's body from the home cellar in which it was buried following the sheriff's death. Philip English died in 1736.

A Break With Charity, a work of historical fiction by Ann Rinaldi, was inspired by the story of Mary and Philip English. Rinaldi told her story from the perspective of the one of the couple's daughters.