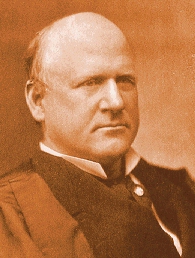

Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes called his colleague John Marshall Harlan the last "tobacco chomping justice." Born in 1833 in Boyle County, Kentucky, Harlan not only chewed tobacco, but drank bourbon, played golf, loved baseball, and wore colorful clothing not often associated with Supreme Court justices. Although sometimes a terror to attorneys while on the bench, Harlan was approachable in person. A man of middle-class values, Harlan alone among the justices of his era was comfortable socializing with Hispanics, Negroes, and Chinese.

Harlan is best known for his eloquent dissent in the 1896 case, Plessy vs Ferguson, which upheld a Louisiana law requiring blacks and whites to ride in separate railroad cars. Harlan criticized the Court's adoption of the "separate but equal" doctrine in these memorable words: "Our Constitution is color blind and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens."

Appointed to the Supreme Court in 1877 by President Rutherford B. Hayes, Harlan was at the time of the Shipp case both the Court's oldest and longest-serving memeber.

Harlan was the justice designated to hear emergency appeals from the Sixth Circuit, which included Tennessee. Harlan thus became the justice who listened on March 17, 1906--just two days before Johnson's scheduled execution--to Noah Parden's plea for Supreme Court intervention in the Johnson case. Alone among justices of his time, Harlan believed that guarantees of the Bill of Rights applied to the states as well as the federal government. It is not surprising then, in a case with as many irregularities as the Johnson case had, that Harlan suspected that the constitutional rights of Ed Johnson had likely been violated in his state trial. After hearing Parden's plea and reading a transcript of the federal district court hearing, Harlan persuaded a majority of Supreme Court justices to gather the next day at the home of Chief Justice Fuller. Harlan's impassioned plea and his expressed belief that Tennessee was about to execute an innocent man convinced his colleagues to stay Johnson's execution and schedule arguments in the case. It was a rare victory in a day in which "state's rights" usually prevailed.

Harlan, of course, was outraged by the lynching of Ed Johnson. He told the press, "Whether guilty or innocent, he had a right to a fair trial." Harlan, along with Oliver Wendell Holmes, took the lead in pressing for a federal response to the lynching in Tennessee. After testimony was completed in the Shipp trial, Harlan supported convictions. According to Mark Curriden and Leroy Phillips, in their recent book Contempt of Court, Harlan told his fellow justices: "The Sheriff is guilty. Any opinion to the contrary is preposterous." Harlan joined the Court's majority opinion convicting Shipp and five other defendants of criminal contempt.