In 1875, a writer of the time observed, there came from coal-mining district of Pennsylvania "an appalling series of tales of murder, of arson, and of every description of violent crime." Mine company superintendents and bosses "could all rest assured that their days would not be long in the land." As John Morse reports in his account of the Molly Maguire Trials, mining officials "everywhere and at all times were attacked, beaten, and shot down, by day and by night,...on the public highways and in their own homes, in solitary places and in the neighborhood of crowds." Largely through the efforts of one man, James McParlan, working undercover and gaining the trust of the secretive organization's leaders, the fearful grip over the anthracite region was broken, and one Molly after another led to his date with the gallows.

Background

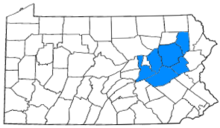

After Frederick Geisenheimer devised a means for smelting iron with anthracite coal in 1833, coal production in the ravines and hills of a five-county district of eastern Pennsylvania began to boom. The Irish potato famine unleashed a wave of immigrants in the 1840s to American shores, and many thousands found jobs in Pennsylvania's anthracite region. Among the Irish immigrants were members of a secret society, with a history of agrarian agitation and violence, called the Molly Maguires (or Ribbonmen). In his undercover report on the Mollys, Pinkerton detective James McParlan described the aim of the Irish Mollys "to take from those who had in abundance and give it to the poor." Mollies sometimes adopted the practice of dressing in women's clothing and visiting shopkeepers. Though the disguise was not intended to fool anyone, it was meant to represent--to the storekeeper from whom handouts or price reductions were demanded--the poor Irish mother begging for food to put on her children's table. Quite possibly, the female disguises used by the Irish Mollys in their intimidations and acts of violence gave rise to their name.

The Ancient Order of Hibernians (AOH) was, throughout most of the northeast in the mid-nineteenth century, a peaceful fraternal organization. In the mineral district, however, the AOH evolved into the organization through which the Molly Maguires sought to achieve their conspiratorial aims. In Pennsylvania's "red axis of violence," the Mollys and AOH--the only organization in the area open to immigrants--were one and the same society. From a period during the 1850s when AOH was associated primarily with political corruption it transformed into an organization willing to use violence to achieve the economic aims of mine-employee members.

By the early 1870s, a reign of terror existed in Shuylkill, Carbon, Luzerne, Columbia, and Northumberland Counties. Any personal slight, reduction in wages, adverse change in working conditions, or imagined grievance against a Molly could inspire a revengeful house burning or cold-blooded murder. In a Molly murder trial, Franklin Gowen, president of the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad whose lines ran through the five-county region, described the terror: "Men retired to their homes at eight or nine o'clock in the evening, and no one ventured beyond the precincts of his own door. Every man engaged in any enterprise of magnitude, or connected with industrial pursuits, left his home in the morning with his hand upon his pistol, unknowing whether he would again return alive. The very foundations of society were being overturned."

No one stood in graver danger than mine superintendents and bosses. If one were to seriously cross a Molly "body-master" (or secretary), his life--according to historian Cleveland Moffett, "was as good as forfeited." Often, the soon-to-be victim would receive a "coffin notice," a written warning depicting a coffin. The Mollys developed a system of reciprocity for their violence. Typically, the body-master of one "district" would ask the body-master of a nearby district to send a team of men over to carry out the murder. (The reciprocal system was designed to make identification of the perpetrators less likely.) After successful completion of a violent mission, assassins usually received a small monetary reward and were treated to a drunken revel.

Unending violence in the anthracite region convinced Franklin Gowen to approach Allan Pinkerton about the possibility of hiring a detective to infiltrate the secret ranks of the Mollys. "I have the very man for you," Pinkerton told Gowen. Pinkerton had in mind thirty-year-old James McParlan, a young man who had advanced rapidly up the Pinkerton ranks. A few weeks later, McParlan accepted the dangerous job. He would earn $12 per week plus expenses and would be required to file daily reports. His orders from Allan Pinkerton were clear: "You are to remain in the field until every cut-throat has paid with his life for the lives so cruelly taken." On October 27, 1873, McParlan, calling himself "James McKenna," arrived in Port Clinton to begin his undercover operation.

At the Sheridan House, a rough drinking establishment in Pottsville, McParlan's drink buying, dancing, card playing, and tough talking won him the admiration of local Mollies. On April 14, 1874, "McKenna" became a member of the Ancient Order of Hibernians, sworn into the organization by Alexander Campbell, who would hang three years later on the basis of McParlan's testimony. It would be more than a year after his initiation, however, before McParlan--under heavy pressure from the mines and the Pinkerton Agency during the Long Strike of 1874-75--would uncover any "murderous plots." By then, McParlan had been chosen as the body-master for the Shenandoah division of the Mollys and, as such, was expected to supply men for sabotage, arson, and murder when called upon by body-masters of other divisions. Through a mix of warnings and diplomacy, McParlan managed to carry out his expected duties without loss of life.

Four prominent murders, and one near murder, in the summer of 1875 provoked widespread outrage and eventually would lead to a series of trials that effectively ended the Mollies' reign of terror. On June 28, 1875, in a revenge attack ordered by Jack Kehoe, four Mollys shot "Bully Bill" Thomas as he stood in a stable and left him for dead, though he survived. McParlan had advance knowledge of the attack (he even had issued the summons for a gathering to plan the murder), but was unable to warn the victim for fear of blowing his cover. (McParlan's failure to warn Thomas of the imminent danger he faced would be a major defense theme in the subsequent trial for the attack.) A week after the attempt on Thomas's life, a police officer named Benjamin Yost was shot and killed as he climbed a ladder to extinguish a street light in the town of Tamaqua. The next month, three Mollys murdered mine superintendent John P. Jones in revenge for his decision to fire and blacklist striking miners. Then, just two days later on September 1, mine superintendent Thomas Sanger and Welsh non-union miner William Uren were gunned down near Wiggan's Patch as they walked to work. (The double murder at Wiggan's Patch prompted a vigilante mob to attack the home of Charles O'Donnell, a suspect in the killings, and kill him and his daughter and son.)

McParlan, in his undercover role, became intimately familiar with the Molly role in the string of summer attacks. He learned from fellow body-master "Powder Keg" Kerrigan that he had issued the order that resulted in officer Yost's killing. Kerrigan told McParlan that Yost was a victim of mistaken identity, as the actual target of the revenge killing was another police officer, Bernard McCarron, who had on several occasions years earlier arrested him on disorderly conduct charges and, more recently, had beaten miner James Duffy. (Yost and McCarron had exchanged their usual beats on the night in question.) Yost's assassins were two members of the Carbon County division of the Mollys, Hugh McGehan and James Doyle. Kerrigan showed McParlan the gun used to kill Yost, a .32 caliber revolver owned by James Roarity. Kerrigan also revealed to McParlan the names of two other men, Duffy and James Carl, involved in the plot. Responsibility for the murder of superintendent John Jones initially fell to McParlan, under orders from county delegate Jack Kehoe to do a "clean job." Claiming to be seriously ill, McParlan dithered and dathered until the assassination was reassigned. McParlan's men did not kill Jones--that job fell to Mollys Doyle and Edward Kelly. The pain McParlan felt over Jones's death was soon aggravated when he learned of the two killing in Wiggan's Patch by five armed killers.

By the end of 1875, the job was clearly taking its toll on McParlan, who was anxious to put an end to the killing: "I am sick and tired of this work," McParlan wrote to Pinkerton. "I hear of murder and bloodshed in all directions. The very sun to me looks crimson; the air is polluted, and the rivers seem running red with human blood. Something must be done to stop it." With the help of McParlan, authorities had been gathering substantial evidence of Molly guilt in the string of murders in the anthracite region. It was time to begin to put the perpetrators on trial. For McParlan's sake, the trials would come just in time--doubts about McParlan were fast growing among the Mollys.

Early Trials

The year of 1876 saw a series of Molly trials and convictions. Arrested by private policeman and prosecuted by mining and railroad company attorneys, the trials, in the words of historian Harold Aurand, "marked one of the most astounding surrenders of sovereignty in American history." Aurand notes that the state's role in the proceeding was limited to providing "the courtroom and hangman." Another troubling feature of the trials was the systematic exclusion of Irish Americans from juries. In the entire series of Molly trials, not a single Irish American was empaneled on a jury. Instead, the fate of the Mollys was decided largely by German immigrants, many of whom admitted to understanding English only poorly.

First to face trial, beginning on January 18, was Michael Doyle of the Molly Maguires' Laffee district, charged with the murder of superintendent Jones. The trial established a pattern for the several Molly trials that followed. Lead prosecutor, mining company attorney Charles Albright, added color to the proceeding by appearing in court wearing his full Civil War uniform (he served as a general in the Union Army) complete with sword. With an unsympathetic judge and a jury of German immigrants, Doyle's fate was sealed. It didn't help the defendant that the prosecution convinced Powder Keg Kerrigan, in exchange for leniency, to testify. On February 1, the jury returned a verdict of guilty on the first-degree murder charge.

Within the days that followed, acting under information provided by McParlan and in a 210-page confession by Kerrigan, arrest warrants were issued for 17 Mollys. In March, Edward Kelly went on trial for the murder of superintendent Jones. He, too, was quickly convicted and sentenced to be hanged. Alex Campbell, owner of the Storm Hill tavern where the Jones murder was allegedly planned, was also successfully prosecuted, despite remarkably flimsy evidence of guilt.

On May 6, James McParlan, guarded by fellow Pinkertons, returned to Pottsville to testify in the Benjamin Yost murder trial of five Mollys. If there remained any doubt among miners about where the true loyalty of "James McKenna" lay, it ended when he answered, in response to the usual question of a witness--"What is your full name?"--"James McParlan." In his 1876 account of the trial, John Morse wrote that the detective's answer brought forth "a deep and universal groan" from "the disheartened mass, who now recognized that the fate of the prisoners was sealed beyond doubt or hope." McParlan proceeded to tell jurors that three of the defendants had confessed to him firsthand, and that Thomas Duffy was the chief conspirator in the murder plot. With McParlan's testimony concerning the plot against Yost, plus the testimony of Kerrigan, convictions were handed down against Duffy, James Carroll, James Roarity, Hugh McGehan, and James Boyle.

On June 27, the trial of Thomas Munley for the murders of Thomas Sanger and William Uren opened. The Munley prosecution rested almost entirely on the testimony of McParlan. Except for the detective's words, the only other evidence of Munley's guilt came from a woman who testified that she saw Munley at the murder scene, gun in hand. In his fiery summation for the prosecution, Franklin Gowen suggested to the jury that Munley belonged to an organization that has claimed "hundreds of unknown victims whose bones now lie moldering over the face of this county--in hidden places, and by silent paths, in the dark ravines of the mountains, and in the secret ledges of rocks." Munley was convicted and sentenced to death.

The Trial of Jack Kehoe and Others

The most celebrated and controversial of the Molly trials opened on August 8. Body-master Jack Kehoe (called "the King of the Mollies") and eight others faced charges of attempted murder for the wounding of William Thomas.

The prosecution presented a compelling case against the defendants. William Thomas, the intended murder victim, identified one of the defendants, John Gibbons, as the man who shot him in the neck. McParlan described the inner workings of the Molly organization and outlined the plot to kill Thomas. McParlan testified that Kehoe "advocated that the best plan was to get a couple of men well armed, and go right up to him on the street and shoot him down in daylight, or any time when they can get him." Defendant Francis McHugh, in a bid to escape the death penalty, corroborated key parts of McParlan's testimony and admitted to participating in a meeting where it was decided that Thomas "should be put out of the road." The warden of the Schuylkill County jail testified that Jack Kehoe, commenting on the result of an earlier Molly trial while in jail awaiting his own said, "I think it will go rough with us too, [but] if we don't get justice, I don't think the old man at Harrisburg will go back on us." (The "old man at Harrisburg" was Pennsylvania Governor Hartranft, elected with labor support, who Kehoe thought likely to issue a pardon.) The warden's testimony was admitted over defense objections of irrelevance, with Judge Walker apparently concluding that Kehoe's words amounted to an admission of guilt.

The defense theory of the case was that McParlan himself was the chief instigator of the crime, and now sought to escape blame by pointing fingers at those far less culpable than himself. Unfortunately for the defense, McParlan made a strong witness, withstanding their efforts to tie him to the crime. As one historian reported, he "stood the test of a severe and searching examination with a degree of straightforward readiness, really quite remarkable in view of the minuteness of the interrogation."

Beyond a vain hope of tying McParlan to the assault, the defense relied chiefly on a lengthy parade of witnesses called to prove the good character of the defendants. According to John Morse's account of the trial, "Probably a more ignorant gang never passed in ludicrous procession through a witness-box." Some witnesses seemed not to understand what was meant by the word "reputation." Others testified that while they themselves knew nothing of Kehoe's evil deeds, they had to admit his reputation was bad. One witness, for example, told jurors: "As to his conduct, that has always been good, but as far as the reputation goes, I never did hear much good." Still others made comments that strained credulity, such as the witness who called Molly Dennis Canning "a gentleman in all respects." Gibbons might have been least well served by the character witnesses, with one admitting that when Gibbons "had liquor in him he was a little wild" and another testifying that he never saw Gibbons do much but drink.

Another strategy of the defense was to suggest that Bill Thomas was a ne'er-do-well who only got what was coming to him. John Morse allows as to how the defense "had an excellent subject to deal with in Thomas" who, he wrote, "does not appear to have been an extremely valuable member of the community." Largely, however, the defense mud-throwing at Thomas missed the mark with the jury.

In closing for the prosecution, Frank Gowen paid tribute to James McParlan, whose dangerous undercover work had caused him to "tremble for his life with as much solicitude as I did for the lives of any upon this earth." Gowen suggested that if McParlan had been able to continue his work for another year, prosecutions could have reached the very top ranks of the national organization of Mollys: "You would have had the pleasure of hanging some men who are not citizens of Schuylkill County. We would have got the head of this Order in Pittsburgh, and we would have got its head in New York."

Gowen's emotional and far-ranging summation led to a motion for a mistrial by the defense. "The learned gentlemen representing the Commonwealth had travelled outside of the evidence in this case, charging men with crimes, to wit, the highest crime known to law, without a scintilla of evidence in this case; charging them with the crime of murder, unproven, untestified to." Judge Walker promptly denied the motion.

Attorney M. M. L'Velle offered the first summation for the defense. He reminded jurors that "the maxim of the law clothes [the defendants] with innocence as pure as doves--yea, as white as snow--until doubt is dispelled in your minds." L'Velle called McParlan an "emissary of death" and a "wily miscreant" who had entrapped well-intentioned young men into committing criminal acts. "Of all the devils who have been in this county plotting against peace and good order, this man, McParlan was the worst." James Ryon closed last for the defense. He asked jurors to be skeptical of McParlan's and McHugh's testimony: "I do not believe that men ought to be hung or imprisoned on the testimony of...accomplices in a crime who are swearing themselves out and swearing others in....The biggest knaves always turn state's evidence, because they want to get themselves out and get somebody else in." If McParlan really was on the side of peace and good order, Ryon argued, he would have immediately warned Thomas of his danger and exposed the plot against him. "McParlan was at the bottom of all these crimes, " Ryon concluded, "and by the aid of the money he was furnished, and the power that he wielded, he not only plotted their commission but succeeded in carrying them out."

The jury took only twenty minutes to decide the case. It returned a verdict of guilty against all twelve defendants, with a recommendation of mercy in the case of Frank McHugh. All defendants except McHugh received the maximum prison term for attempted murder of seven years.

Later Trials

On August 15, seven Mollys went on trial for "aiding and assisting to reward Thomas Hurley for the murder of Gomer James." McParlan once again provided the key testimony, describing an AOH meeting in Tamaqua where a reward for Hurley was discussed. Additional drama in the trial came when Patrick Butler broke down on the stand and admitted guilt. After only fifteen minutes of deliberation, the jury returned guilty verdicts against all defendants, with a recommendation of mercy for Butler.

Not satisfied with a mere prison term for Jack Kehoe, authorities launched in late 1876 a prosecution of Kehoe for a murder committed in 1862. In June of that year, mine foreman Frank Langdon, expressed strong pro-Union sentiments at a public meeting. Jack Kehoe, along many other Irish miners, shared anti-Union sentiments (Kehoe, for example, used the occasion to spit on the American flag). Kehoe allegedly told Langdon after his speech, "You son of a bitch, I'll kill you." It was Kehoe's second threat against Langdon in a matter of weeks, the first coming after the foreman docked Kehoe's pay. Leaving the meeting, Langdon received a severe beating from a gang of men and died the following day. No witness placed Kehoe at the scene of the attack--and one witness specifically testified that he was not among the gang of men who beat Langdon. Historian Kevin Kenny, author of Making Sense of the Molly Maguires, called Kehoe's first-degree murder conviction fifteen years later "unquestionably the most dubious of all the verdicts handed down to the Molly Maguires."

The last of the major Molly trials opened on February 8, 1877 in Bloomsburg. Patrick Hester, Peter McHugh and Patrick Tully faced trial for the murder of mine superintendent Alexander Rea in 1868. A detailed confession by "Kelly the Bum" (Manus Cull) made the trial outcome a foregone conclusion and all three defendants received sentences of death.

Epilogue

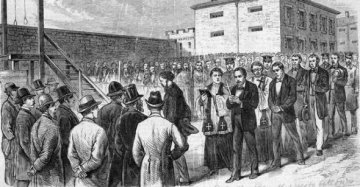

Appeals proved unsuccessful. Twenty Mollys made walks to the gallows. Thursday June 21, 1877, known as "Black Thursday" saw ten miners hang, six in Pottsville and four in Mauch Chunk. Jack Kehoe's date with the rope came on December 18, 1878, following the denial of his pardon appeal by Governor Hartranft. (Later, however, in 1970, at the request of Kehoe's great-grandson, Joe Wayne, Pennsylvania Governor Milton Shapp issued Kehoe a full posthumous pardon.)

James McParlan continued his work for the Pinkerton Detective Agency. In 1906, while head of the agency's Denver office, McParlan took the lead role in investigating the assassination of Idaho Governor Frank Steunenberg. His work led to charges being filed against "Big Bill" Haywood and two other leaders of the Western Federation of Miners, but the labor leaders were successfully defended by Clarence Darrow in a celebrated trial.

Franklin Gowen, the chief prosecutor in several of the major Molly trials, became President of the Reading Railroad. After the railroad fell into bankruptcy in 1889, Gowen committed suicide.

The Ancient Order of Hibernians cut its ties with the Mollys by the late 1870s and renewed its association with the Catholic Church. The early lodges in Pennsylvania's anthracite region were written out of AOH history.

The Molly trials fueled discrimination against Irish Americans and suspicion of the trade union movement, both of which lingered for decades. With the executions, a measure of peace returned to the Pennsylvania mining district. In the words of Kevin Kenny, "A particular Irish tradition of retributive justice...died on the scaffold with the Molly Maguires."