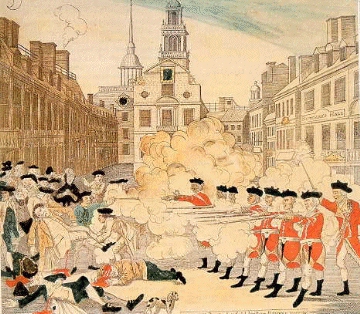

Although it has been over two centuries since the moonlit March night in 1770 when British soldiers killed five Bostonians on King Street, people still debate responsibility for the Boston Massacre. Does the blame rest with the crowd of Bostonians who hurled insults, snowballs, oyster shells, and other objects at the soldiers, or does the blame rest with an overreacting military that violated laws of the colony that prohibited firing at civilians? Whatever side one takes in the debate, all can agree that the Boston Massacre stands as a significant landmark on the road to the American Revolution.

The Massacre

In the snowy winter of 1770, many residents of Boston harbored deep resentment against the presence of British military in their city. Two regiments of regulars had been quartered in Boston since September of 1768, when they had landed in response to a call by the Governor to restore order and respect for British law. Trouble had arisen earlier that summer when Boston importers refused to pay required custom duties. Some Bostonians disliked soldiers because they competed for jobs, often willing to take part-time work during their off-duty hours for lower wages. Seamen saw the soldiers as enforcers of the detested impressment laws, which authorized persons to be seized and forced to serve in the British Navy.

Clashes between soldiers and civilians were on the rise in early March. On March 2, a fist fight broke out between soldiers and employees of John Gray's Ropewalk after one of the employees insulted a soldier. A cable-making employee reportedly asked a passing soldier, "Do you want work?" When the soldier replied that he did, the employee told the soldier, "Wee then, go and clean my shithouse." The angry soldier returned later with about a dozen fellow soldiers, and the fight ensued.

The tragedy of March 5 began with a simple dispute over whether a British officer had paid a bill to a local wig-maker. The officer was walking down King Street when Edward Garrick, the wigmaker's apprentice, called out, "There goes the fellow who hath not paid my master for dressing his hair." The officer with the new hair, Captain John Goldfinch, passed on without acknowledging Garrick. But Garrick persisted, telling three passers-by that Goldfinch owed him money. A lone sentry named Hugh White overheard Garrick's remarks. White told the apprentice, "He is a gentleman, and if he owes you anything he will pay for it." Garrick's answer--that there were no gentlemen left in the regiment--caused White to leave his post and confront Garrick. After a brief, heated exchange of words, the sentry struck Garrick with his musket, knocking him down.

Soon a small crowd, attracted by the ruckus between White and Garrick, gathered around the lone guard and began taunting him: "Bloody lobster back! Lousy rascal! Lobster son of a bitch!" The crowd grew to about fifty. Some in the mob of mostly young men threw pieces of ice at White, and he grew fearful. As the crowd continued to increase in size and hostility, White retreated from his sentry box to the Custom House steps, loaded his gun, and began to wave it about. White knocked on the door and banged the butt of his gun against the steps. Desperate, White yelled, "Turn out, Main Guard!"

Meanwhile, a few blocks north, another confrontation between civilians and Redcoats broke out. Under a barrage of snowballs, a group of soldiers was hustled into its barracks. A third mob, this one about two hundred strong and carrying clubs, gathered in Dock Square. A tall man with a white wig and a red coat did his best to rile up the crowd. Trouble seemed to be erupting all over the city. "Let's away to the Main Guard!" someone shouted, and the crowd began streaming down an alley toward King Street. Someone pulled the fire bell rope at the Brick Meeting House, bringing dozens of more residents out into the restless streets.

In front of the Main Guard, officer for the day, Captain Thomas Preston, paced back and forth for nearly thirty minutes, worrying about what to do. If he did nothing, he thought, White might be killed by the mob. But trying to rescue White carried its own risks, as the soldiers would be vastly outnumbered by the frightening mob. Moreover, Preston knew well that Province law forbid the military from firing on civilians without the order of a magistrate. Finally, Preston made his decision. "Turn out, damn your bloods, turn out!" he barked at his men.

The Boston Massacre (engraving by Paul Revere)(the engraving is not an accurate depiction of the event)

Preston and seven other men, lined up in columns of twos, began moving briskly across King Street with empty muskets and fixed bayonets. They pushed on through the thick crowd near the Custom House. Managing to make it to the beleaguered Private White, Preston ordered the sentry to fall in. Preston tried to march the men back to the Main Guard, but the mob began pressing in. Hemmed in, the soldiers lined up--about a body length apart--in a sort of semi-circle facing the crowd that had grown to between fifty and a hundred people. Many in the crowd threw missiles of various sorts--chunks of coal, snowballs, oyster shells, sticks--at the soldiers.

Captain Preston shouted for the crowd to disperse. A large club-wielding man named Crispus Attucks--a forty-seven-year-old man of mixed race--moved forward, grabbed one of the soldier's (Hugh Montgomery's) bayonets, and knocked him to the ground. Montgomery rose, shouting "Damn you, fire!" and unloading his musket in the direction of the crowd. Soon after--estimates varied from six seconds to over a minute--Montgomery shouted "Fire!" The other soldiers also began firing. A blast from the gun of Matthew Killroy hit Samuel Gray as he stood with his hands in his pockets, blowing a hole in his head "as big as a hand." From another gun, two balls hit Crispus Attucks in the chest. As the mob moved toward the soldiers, more guns fired. A seventeen-year-old apprentice to an ivory turner, as well as a sailor, were hit by balls fired into their chests. In all, five civilians lay dying in the streets; another half dozen lay injured. The soldiers loaded their weapons and prepared to fire again when Captain Preston (according to his own statement) yelled, "Stop firing! Do not fire!" The Boston Massacre was over.

Arrests and Imprisonment

Word of the shootings reached Acting Governor Thomas Hutchinson in this North Square home. Hutchinson rushed to King Street where he found an angry crowd and a shaken Captain Preston. Hutchinson confronted Preston: "Do you know, Sir, you have no power to fire on any body of the public collected together except you have a civil magistrate with you give orders?" After talking with Preston, Hutchinson proceeded upstairs in the Town House, where several members of the Council had already gathered. He assured Council members that he would do his best to see justice done, then he stepped out onto a balcony overlooking the scene of the massacre and asked the crowd for calm: "Let the law have its course. I will live and die by the law."

Governor Hutchinson

After midnight, Justices Richard Dania and John Tudor gave the sheriff a warrant for the arrest of Captain Preston. Preston was arrested and brought to the Town House, where he was interrogated for an hour by the two justices about the shooting. At three o'clock in the morning, the justices concluding they had "evidence sufficient to commit him," sent Preston to the jail where he would remain for the next seven months.

Later that morning a thirty-four-year-old Boston attorney, John Adams, was visited in his office near the stairs of the Town Office by a Boston merchant. "With tears streaming from his eyes" (according to the recollection of Adams), the merchant, James Forest, asked Adams to defend the soldiers and their captain, Thomas Preston. Adams understood that taking the case would not only subject him to criticism, but might jeopardize his legal practice or even risk the safety of himself and his family. But Adams believed deeply that every person deserved a defense, and he took on the case without hesitation. For his efforts, he would receive the modest sum of eighteen guineas.

John Adams

A week after the massacre, at the request of Attorney General Jonathan Sewall, a grand jury handed down indictments against Captain Preston and eight soldiers. About the same time, Preston offered his version of the events of March 5 in a deposition:

About 9 some of the guard came to and informed me the town inhabitants were assembling to attack the troops, and that the bells were ringing as the signal for that purpose and not for fire, and the beacon intended to be fired to bring in the distant people of the country. This, as I was captain of the day, occasioned my repairing immediately to the main guard. In my way there I saw the people in great commotion, and heard them use the most cruel and horrid threats against the troops. In a few minutes after I reached the guard, about 100 people passed it and went towards the custom house where the king's money is lodged. They immediately surrounded the sentry posted there, and with clubs and other weapons threatened to execute their vengeance on him. I was soon informed by a townsman their intention was to carry off the soldier from his post and probably murder him. On which I desired him to return for further intelligence, and he soon came back and assured me he heard the mob declare they would murder him. This I feared might be a prelude to their plundering the king's chest. I immediately sent a non-commissioned officer and 12 (sic) men to protect both the sentry and the king's money, and very soon followed myself to prevent, if possible, all disorder, fearing lest the officer and soldiers, by the insults and provocations of the rioters, should be thrown off their guard and commit some rash act.

Jail-cell writings of Preston appeared in the Boston Gazette. In an early letter to the paper, Preston extended his "thanks...to the inhabitants of this town--who throwing aside all party and prejudice, have with the utmost humanity and freedom stept forth advocates for truth, in defense of my injured innocence." On June 25, however, a letter Preston sent to London found its way into Boston papers and undermined whatever goodwill he might have built up earlier. In his London letter, Preston complained about Bostonians who "have ever used all means in their power to weaken the regiments and to bring them into contempt, by promoting and aiding desertions, and by grossly and falsely promulgating untruths concerning them." He wrote that bitter "malcontents" were maliciously "using every method to fish out evidence to prove [the March 5 shooting] was a concerted scheme to murder the inhabitants."

As Preston and the eight indicted soldiers languished in jail, Boston residents (including such notable figures as Samuel Adams and John Hancock) pressed demands on Hutchinson and Colonel Dalrymple for the "instant removal" of all troops from the city of Boston. The two men initially balked at the demand, but finally gave into overwhelming public pressure. The two regiments evacuated the city and moved to Castle William.

Samuel Adams also busied himself--in today's jargon--with "spin control." He participated in writing A Short Narrative of the Horrid Massacre in Boston, a decidedly slanted, anti-British account of the events of March 5. The goal of the publication was to refute charges that Bostonians were the aggressors in the incident and to build up public pressure against the British military. In letters to the Boston Gazette, Samuel Adams became the principal defender of Crispus Attucks, denying accounts that Attucks had attacked a soldier with a club. Wrote Adams, Attucks "had as good a right to carry a stick, even a bludgeon, as the soldier who shot him had to be armed with musket and ball."

The period after the massacre was tough for Acting Governor Hutchinson. Two weeks after the Massacre, Hutchinson wrote: "In matters of dispute between the King and the colonies government is at an end and in the hands of the people. Still, Hutchinson resisted demands for quick trials--"so that," he said, "people may have time to cool."

The Trials

Queen Street Courthouse, scene of the trial

Authorities determined that Captain Preston should be tried separately from the eight soldiers. On October 21, the soldiers objected in a letter to the Court: "We poor distressed prisoners beg that ye would be so good as to let us have our trial at the same time with our Captain, for we did our Captain's orders, and if we do not obey his command should have been confined and shot for not doing it." The soldiers feared--not without reason--that Preston's best defense lay in denying that he gave any orders to fire, and that their own best defense lay in claiming that they only followed their Captain's orders. If Preston were to proceed to trial first, their defense might well be compromised. The conflict between the interests of Preston and the soldiers must have presented a dilemma for John Adams, who had agreed to defend them both. Under the ethical standards of today, Adams should have made a choice between representing either Preston or the soldiers, but such conflicts were viewed differently in the 1700s. The soldiers' request for a joint trial was denied without explanation.

Captain Preston's trial for murder came first. The trial ran from October 24 to 30 at the Queen Street Courthouse. The prosecution was led by Samuel Quincy, the colony's solicitor general, and prominent Boston lawyer, Robert Paine. Josiah Quincy assisted John Adams in his defense of Preston.

Trial scene

The central issue concerned whether or not Preston gave the order to fire on the civilians. Preston's steadfast denial that he gave an order to fire was supported by three defense witnesses, while four witnesses for the prosecution swore that did give the fatal order. The most convincing of the prosecution eyewitnesses was Daniel Calef:

I was present at the firing. I heard one of the Guns rattle. I turned about and lookd and heard the officer who stood on the right in a line with the Soldiers give the word fire twice. I lookd the Officer in the face when he gave the word and saw his mouth. He had on a red Coat, yellow Jacket and Silver laced hat, no trimming on his Coat. I saw his face plain, the moon shone on it.

Although the trial was transcribed in shorthand, no copy survives, and Preston's testimony must be surmised from the deposition he gave in advance of trial. In Preston's deposition, he offered the following account of the actual shooting:

Some well-behaved persons asked me if the guns were charged. I replied yes. They then asked me if I intended to order the men to fire. I answered no, by no means, observing to them that I was advanced before the muzzles of the men's pieces, and must fall a sacrifice if they fired; that the soldiers were upon the half cock and charged bayonets, and my giving the word fire under those circumstances would prove me to be no officer. While I was thus speaking, one of the soldiers having received a severe blow with a stick, stepped a little on one side and instantly fired, on which turning to and asking him why he fired without orders, I was struck with a club on my arm, which for some time deprived me of the use of it, which blow had it been placed on my head, most probably would have destroyed me. On this a general attack was made on the men by a great number of heavy clubs and snowballs being thrown at them, by which all our lives were in imminent danger, some persons at the same time from behind calling out, damn your bloods-why don't you fire. Instantly three or four of the soldiers fired, one after another, and directly after three more in the same confusion and hurry.

John Adams evidently succeeding in creating doubts in the minds of jurors as to whether Preston ever gave an order to fire. The sequestered twelve-man jury (which had survived the trial on a diet of "biscett and cheese and syder" along with "sperites licker") deliberated only a few hours before acquitting Preston on all charges.

Eight weeks later, the eight soldiers faced trial. A transcript of the trial, formally called Rex v Weems et al, survives, giving us a much more complete picture of the proceeding. Witnesses testified as to military-civilian clashes such as the one at Gray's Ropewalk three days before the massacre, as well as to the events on the night of March 5 near King Street.

Justice Peter Oliver

The prosecution's most damning testimony came from Samuel Hemmingway, who swore that Private Matthew Killroy--identified by another prosecution witness as the man who shot citizen John Gray--"would never miss an opportunity, when he had one, to fire on the inhabitants, and that he had wanted to have an opportunity ever since he landed."

The defense presented testimony to support its theory that the soldiers fired in self-defense. Defense witnesses such as James Bailey presented the picture of an out-of-control gang of hooligans. Bailey described the soldiers being pelted by large chunks of ice and other objects. Bailey also testified that he saw Crispus Attucks knock down Private Montgomery with "a large cord-wood stick." Adams asked the jury to consider whether "it have been a prudent resolution in them, or in any body in their situation, to have stood still, to see if the [the mob] would knock their brains out, or not?"

Of particular interest in the defense case was testimony concerning the dying statement of Patrick Carr, one of the victims in the massacre. It is the first recorded use of the "dying declaration" exception to the rule that excludes hearsay evidence:

Q. Was you Patrick Carr's surgeon?

A. I was...

Q. Was he [Carr] apprehensive of his danger?

A. He told me...he was a native of Ireland, that he had frequently seen mobs, and soldiers called upon to quell them...he had seen soldiers often fire on the people in Ireland, but had never seen them bear half so much before they fired in his life...

Q. When had you the last conversation with him?

A. About four o'clock in the afternoon, preceding the night on which he died, and he then particularly said, he forgave the man whoever he was that shot him, he was satisfied he had no malice, but fired to defend himself.

After presenting over forty witnesses, John Adams summed up for the defense. His eloquent speech blended law and politics. He finished by telling the jury that this was a case of self-defense:

I will enlarge no more on the evidence, but submit it to you.-Facts are stubborn things; and whatever may be our wishes, our inclinations, or the dictates of our passions, they cannot alter the state of facts and evidence: nor is the law less stable than the fact; if an assault was made to endanger their lives, the law is clear, they had a right to kill in their own defence; if it was not so severe as to endanger their lives, yet if they were assaulted at all, struck and abused by blows of any sort, by snow-balls, oyster-shells, cinders, clubs, or sticks of any kind; this was a provocation, for which the law reduces the offence of killing, down to manslaughter, in consideration of those passions in our nature, which cannot be eradicated. To your candour and justice I submit the prisoners and their cause.

Justices Trowbridge and Oliver instructed the jury. Justice Trowbridge told the twelve men of Boston that "malice is the grand criterion that distinguishes murder from all other homicides." Justice Oliver discussed Patrick Carr's dying statement to his physician: "This Carr was not upon oath, it is true, but you will determine whether a man just stepping into eternity is not to be believed, especially in favor of a set of men by whom he had lost his life."

After less than three hours deliberation, the jury acquitted six of the soldiers on all charges. Hugh Montgomery and Matthew Killroy--the only two soldiers clearly proven to have fired--were found guilty of manslaughter.

On December 14, Montgomery and Killroy came into court. Asked if there was any reason why the sentence of death should not be passed, the two men invoked "the benefit of clergy," a plea that shifted their punishment from imprisonment to the branding of their thumbs . As John Adams looked on, the men held out their right thumbs for Sheriff Stephen Greenleaf to brand.

Branding of the convicted soldiers

Not surprisingly, reactions to the verdicts varied. Samuel Adams expressed his displeasure in a letter signed "Vindex":

They not only fired without the order of the civil magistrate but they never called for one, which they might easily have done. They went down...armed with muskets and bayonets fixed, presuming they were clothed with as much authority by the law of the land as the posse comitatus of the country with the high sheriff at their head.

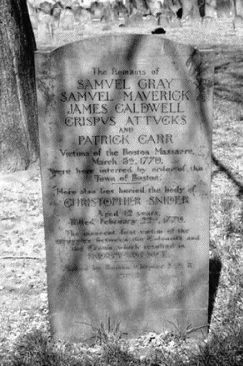

Grave of five victims of the massacre

On the other hand, Samuel's second cousin, John Adams, found the verdicts deeply satisfying. Looking back at the trials after an illustrious career that had taken him to the White House, Adams said:

The Part I took in Defence of Cptn. Preston and the Soldiers, procured me Anxiety, and Obloquy enough. It was, however, one of the most gallant, generous, manly and disinterested Actions of my whole Life, and one of the best Pieces of Service I ever rendered my Country. Judgment of Death against those Soldiers would have been as foul a Stain upon this Country as the Executions of the Quakers or Witches, anciently. As the Evidence was, the Verdict of the Jury was exactly right.

That is not to say, however, that the soldiers acted appropriately. When one reads the ninety-six depositions taken in the Preston trial, it becomes fairly obvious that before the massacre, many British soldiers acted as bullies and all but welcomed trouble. The soldiers ended up getting more than they bargained for--and then reacted as one might expect in a life-threatening situation.

Samuel Adams fanned the flames of opposition to the military occupation of Boston. He hoped the public outrage over the verdicts could lead to a speedy exit of British troops from his city. Trials decide the fate of defendants, but sometimes they also influence the fates of nations.

After the trials, a sort of surface normalcy returned to Boston. But beneath the surface, in the hearts and minds of citizens, opposition to the occupation ran deep. The Revolution was coming.