Stamped With Glory: Lewis Tappan and the Africans of the Amistad

by Douglas O. Linder

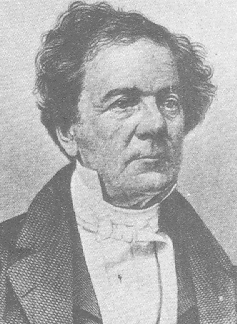

Tappan

|

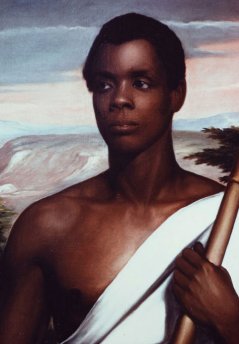

Cinque

|

1

The officers and crew of the Tecora waited at sea for darkness to come to Cuba. Closer to shore, British cruisers patrolled the waters looking for slave ships. The British had been trying for nineteen years, since 1820, to enforce the provisions of a treaty between England and Spain that prohibited the importation of slaves to Cuba and other Spanish dominions. The captain of the Portuguese slave ship knew, however, that the odds were with him. Two thousand miles of Cuban coastline made capture at sea difficult, and once on land the slavers were outside British authority and under the protection of complicit Cuban officials.

The weak glow of lights on shore guided the Tecora to a secluded inlet along the Cuban shoreline. Quickly the crew loaded the ship’s cargo of over three hundred African men, women, and children—none over the age of twenty-five—into small boats and carried them to land. After everyone was on the beach, the crew hustled the Africans on a three-mile trek through the jungle. Arriving at their destination, the crew locked the Africans in crude human warehouses.

About ten days after their arrival in Cuba, the captives marched again, this time to a barracoon, or slave stockade, within sight of the city of Havana. The Misericordia barracoon stood just off a busy road that connected the city and the white palace of the Governor General. The surrounding structures of the barracoon formed a large courtyard, where the Africans exercised and where they could be observed by Cuban spectators.

Thin or depressed blacks did not command high prices, so slave importers treated their human merchandise relatively well. Employees of the Martinez Company fed and clothed the Africans, gave them tobacco, and rubbed their skin with palm oil to make it shine.

Two Spanish dons came to the barracoon in late June to select new slaves for their plantations in Puerto Principe, on the northwest coast of the island. Jose Ruiz, twenty-four, made his selections carefully. He ordered blacks to stand in a row, then inspected their bodies and teeth one-by-one. Ruiz bought the forty-nine adult males that passed his inspection for $450 each. Fifty-eight-year-old Pedro Montes, meanwhile, selected four children, three of them girls.

The two Cuban plantation owners obtained fraudulent passports for their human property from the captain general--passports that would allow them to transport their “black Ladinos” to Puerto Principe by sea. The passports contained descriptions of each black along with the false Spanish names that they had been given by their purchasers.

On June 28, 1839, the Spanish dons loaded the Africans on a chartered two-masted black schooner called the Amistad. Although they had papers, Montes and Ruiz knew their vessel was subject to search by British slave patrol boats. The papers showing the captives to be ladinos, or legal slaves born in Spanish territory, would not fool a conscientious enforcer of the anti-importation treaty. None of the slaves spoke Spanish and the children were far too young to have been born in Cuba before 1820. At midnight, the Amistad, captained by Ramon Ferrer, sailed out of Havana harbor with its cargo of fifty-three slaves and about $40,000 in provisions.

For the Africans, the voyage was to be endured, not enjoyed. Crew members placed iron collars around the neck of each slave. They connected each collar by a chain to another slave, and whole string of collars they chained to the wall. The Africans were kept in the suffocating heat of the hold most of the voyage. Time on deck was limited to meals and to brief relief breaks, taken a few at a time. Discipline was strict. Ruiz ordered crew members to flog a captive who took more than his alloted share of water.

A sadistic joke turned the Africans to thoughts of mutiny. One of the captives, a physically impressive twenty-five-year-old named Cinque, used sign language to ask the ship’s cook, Celestino, what would happen to them when they reached their destination. Celestino smiled and pointed to a nearby pile of beef. Indicating with his hands, Celestino told Cinque that the slaves would have their throats slit, be chopped to pieces, salted, and eaten as dried meat. Cinque, who had seen the barbarism of the Middle Passage, believed him.

The startling news led Cinque to call a conference among the slaves on their third day at sea. One of the slaves, a boy named Kinna, later recounted what happened:

We feel bad, and we ask Cinque what to do. Cinque say, “Me think and by and by I tell you.” Cinque then said, “If we do nothing, we be killed. We may as well die in trying to be free as to be killed and eaten.”

A nail hidden by Cinque under his arm became the captives’ means to freedom. Using the nail, Cinque freed himself and the others from their iron chains. He and another captive, Grabeau, located a box of sugar cane knives with two-foot-long blades. About 4:00 A.M. on a stormy July 2, most of the adult Africans climbed up the hatchway. Cinque found the cook and killed him with a single blow. A crew member who witnessed the attack screamed “Murder!” awakening Ruiz and Montes. Cinque and other slaves began closing in on Captain Ferrer and his cabin boy, Antonio. Waving his dagger to fend off an attack, the captain yelled to Antonio, “Throw some bread at them.” The captain fought ferociously, killing one African and wounding two others, but in the end he was struck by Cinque, then strangled by other captives. Attention turned to Montes, who flailed away with a knife in one hand and a pump handle in the other. Struck by oars and cane knifes, the seriously injured Montes managed to stagger down to the hold and hide behind a food barrel. Two sailors jumped over board. Antonio was tied to an anchor. Ruiz surrendered. Cinque discovered Montes the next morning. He stood over him, ready to inflict a fatal blow, when another African, Burnah, grabbed him and persuaded him to spare the slave owner’s life.

The mutiny had succeeded. The Africans controlled the Amistad. They ordered Montes to head east across the Atlantic--to Africa.

2

Lewis Tappan, as an abolitionist and a devout Christian, found the spectacle of Emancipation Day disheartening and scandalous. Celebrated on the Fourth of July, the holiday commemorated the freeing of New York’s last slaves on that date in 1827. Most of New York City’s 14,000 Negroes saw Emancipation Day as an occasion for raucous celebration. Dressed in “outrageous costumes,” they paraded through the streets blowing trumpets, banging drums, and drinking cider and rum.

Tappan decided to offer an alternative to the carousing he found so distasteful. On Emancipation Day in 1834, he opened the doors of his Chatham Street Chapel for a special service. Along with the blacks he hoped would come, came some that he hoped would not: a mob of mostly lower-income, pro-slavery whites filled the upper galleries. As Tappan finished a “forcible and impressive” reading of the Declaration of Sentiments--the statement of principles adopted by abolitionists at their first national convention in Philadelphia seven months earlier--the unruly crowd began to hoot and stamp. Minutes later, as choirs of Negro and whites attempted to sing a new hymn by John Greenleaf Whittier, prayer books and insults began flying from the balconies. It took a squad of watchmen dispatched by the mayor to head off more serious violence--at least for the day.

Three days after the Emancipation Day disturbance at Chatham Street Chapel, things went from bad to worse. A group of Negro parishioners gathered in the Chapel refused the demand of members of a white group, the Sacred Music Society, that they leave the premises. Word of the Negroes’ stand spread. Soon rioters were beating blacks and tossing benches—not just books--from balconies. The church caretaker ran to Lewis Tappan’s home at 40 Rose Street, where he interrupted the Monthly Concert for the Enslaved. Tappan rushed to the Chapel, only to discover that police had already dispersed the mob.

At the Tappan home, Susan Tappan listened worriedly as a mob yelled for her husband to come out. Returning home, Tappan pushed his way to his front door “amidst a tremendous noise, mingled groans, hisses, and execrations.” Hired guards finally persuaded the mob to leave.

The next afternoon, Tappan, with threats against him swirling all around New York, moved his family to Harlem Village. As darkness fell that hot, muggy night, a man on a white horse led a mob back to Rose Street. Rowdies broke open the door of Tappan’s home, smashed windows and hurled the family’s furniture out into the street of the usually quiet neighborhood. Blue-collar whites inflicted most of the damage, but merchants and even a church deacon looked on in approval. In the center of Rose Street, men set afire a large pile of bedding, pictures, furniture, and window frames, and other Tappan family belongings.

The Tappans returned the next day to inspect the damage. They faced their travails bravely. Lewis Tappan later commented, “When my wife saw the large chimney glass--which we purchased eighteen years ago and which I often said looked too extravagant-- was demolished, she laughed and said, ‘you got rid of that piece of furniture that troubled you so much.’” Characteristically, Tappan saw his personal misfortune as an opportunity. He chose not to repair his home that summer. Let it stand as it is, he said, to serve as a “silent Anti-Slavery preacher to the crowds who will flock to see it.”

New York City boiled with trouble in the summer of 1834. Newspapers ran virulent attacks on abolitionist leaders. Rumors circulated that pro-slavery merchants had ordered their employees to ambush Tappan “expressly to tar and feather” him. With one of eight people unemployed, whites feared that black competition in the labor market would make things worse. Then there was the issue of interracial marriage: opponents of abolition used the bugaboo to raise levels of hostility to anti-slavery movement leaders to a fever pitch.

Undaunted by violence, insults, and threats, Lewis Tappan outlined to fellow abolitionists a bold propaganda effort to win the hearts and minds of Americans. Apathy, he believed, was the only great enemy of abolition. Tappan proposed a massive mailing of anti-slavery publications to clergy, educators, and local officials on both sides of the Mason-Dixon Line. Tappan doubted that abolition could come through timid, halfway measures: “If you wish to draw off the people from a bad or wicked custom, you must beat up for a march; you must make an excitement, do something that everybody will notice.”

In July 1835, Tappan unleashed a flood of anti-slavery writings: the lively journal, Human Rights, the newsy Emancipator, the Anti-Slavery Record embellished with woodcuts, and a children’s magazine, Slave’s Friend. “Moral suasion,” Tappan optimistically believed, would separate slaveholders from Christian fellowship, convince legislators to gradually tighten state and federal controls on slavery, and cause slave states to give up the immoral institution of slavery—all without much bloodshed. In a ten-month period, the Society mailed over one million anti-slavery pieces.

Tappan’s propaganda effort outraged pro-slavery southerners. On July 29, 1835, angry citizens of Charleston broke into the U. S. Post Office and hauled off mailbags that had recently arrived from New York City. The next evening, 3,000 Charlestonians assembled on the parade grounds to watch slavery supporters burn a pile of abolitionist mailings under the hanging effigies of despised abolitionists. One rabid southerner offered a $50,000 reward was offered for Tappan’s head, delivered to New Orleans. Calls for the extradition of abolitionist leaders came from southern newspaper editors, governors, and attorney generals. A grand jury in Virginia indicted Lewis Tappan and other members of the American Anti-slavery Society’s Executive Committee.

The South’s reaction to Tappans’ mail campaign caused many northern editorialists--not previously sympathetic to the abolitionist cause--to rally to their defense. Editors denounced threats of violence and defended the right to free speech. Public opinion, especially among northern churchgoers, began to turn against slavery.

But growing abolitionist sentiments only fueled southern anger. In 1836, Lewis Tappan opened a package and discovered in a box a slave’s ear and an accompanying note recommending the body part for his “collection of natural curiosities.” In another package, he found a piece of rope suggesting a gallows.

Tappan responded to these attempts at intimidation by placing in his breast pocket his only weapon, a copy of the New Testament. He seemed invigorated by danger. In a response to a threatening letter from a member of a South Carolina vigilance committee, Tappan wrote: “We will persevere, come life or death. If any fall by the hand of violence, others will continue the blessed work.”

Persevere Tappan did. But the optimism of the mid-1830s gave way to doubts. An economic depression and internal fighting among factions of abolitionists slowed anti-slavery momentum. Tappan began devoting more and more of his attention to trying to heal fundamental schisms within the abolitionist movement. He served as a bridge between the evangelical, “respectable” New York faction and the more pacifist and utopian faction based in Boston and led by William Lloyd Garrison. By 1839, keeping the warring groups together was proving increasingly difficult. The movement needed a cause that abolitionists of all stripes could rally around—it needed intervention, divine or otherwise.

Then the Amistad turned up.

3

“They made fools of us,” said Cinque, “and did not go to Sierra Leone.” The leader of the Africans of the Amistad related the story of his six weeks at sea from his jail cell. In the daytime, he explained through an interpreter, he could tell by the sun that the Spaniards were heading east, toward Africa. But at night the Spaniards deceived them, and turned the vessel the other way. We got here, Cinque said, and we did not know where we were.

Captain Henry Green, a sea captain, and several companions were shooting birds among the dunes at the eastern tip of Long Island on the morning of August 26, 1839, when they encountered several black men wearing only blankets. One of the blacks--who spoke a little broken English--asked, “What country is this?” Green replied, “This is America.” “Is it a slave country?” the African inquired. No, Green answered, “it is free here, and safe, and there are no Spanish laws here.” Cinque whistled. The other Africans gathered on the beach sprang to their feet and shouted. Fearing attack, Captain Green and his associates dashed toward their wagon for their guns. Cinque, however, demonstrated the Africans’peaceable intentions by handing his cutlass and gun to the Americans. The rest of the blacks did the same.

The Africans led Green and the others to a point in the dunes where they could see a black schooner, flagless with its sails in tatters, sitting at anchor a mile or so from the beach. Another smaller boat rested on the beach, guarded by more blacks.

The Africans made Green an offer. The ship and all of its cargo, they proposed, in return for provisions and help in sailing back to their African homeland. Green expressed interest—especially in the gold doubloons that the Africans said were in the Amistad’s trunks.

A brig of the U. S. Coast Guard, the Washington interrupted Captain Green’s dreams of riches. The Washington came alongside the Amistad. The commander of the brig, Lieutenant Thomas Gedney, sent a contingent of seven armed men led by Lieutenant Richard Meade to investigate the schooner. The men boarded the schooner and ordered, at gunpoint, all hands below the deck. Two Spaniards emerged from below exclaiming, “Bless our Holy Virgin; you are our preservers.” Jose Ruiz, the younger of the two men, spoke English. Eagerly, he began to tell the tale of mutiny, blood, deceit, and desperation aboard the Amistad.

After listening to the Spaniard’s story, Meade dispatched four of his men to round up the Africans on shore. It took a warning shot and drawn cutlasses, but soon the sailors were heading back to the Amistad with their black captives, including Cinque. Cinque was back on board the schooner for only a moment when he suddenly jumped overboard. A detachment of sailors chased after him in a boat, but each time they approached, he dove under the water only to resurface some distance away. The sailors finally pulled the exhausted African from the sea twenty minutes later with a boat hook.

Gedney ordered the Amistad towed to New London, Connecticut, where the arrival of the mysterious schooner dominated the local news. On August 26, a sensational story ran in the New London Gazette:

[Pedro Montes] is the most striking instance of complacency and unalloyed delight we have ever witnessed, and it is not strange since only yesterday his sentence was pronounced by the chief of the bucanniers, and his death song chanted by the grim crew, who gathered with uplifted sabres around his devoted head, which, as well as his arms, bear the scars of several wounds inflicted at the time of the murder of the ill-fated captain and crew. He sat smoking his Havana on the deck, and to judge from the martyr-like serenity of his countenance, his emotions are such as rarely stir the heart of man….

On board the brig we also saw Cinques, the master spirit and hero of this bloody tragedy, in irons. He is about five feet eight inches in height, 25 or 26 years of age, of erect figure, well built, and very active. He is said to be a match for any two men aboard the schooner. His countenance, for a native African, is unusually intelligent, evincing uncommon decision and coolness, with a composure characteristic of true courage, and nothing to mark him a malicious man. He is a negro, who could command in New Orleans, under the hammer, at least $1500….

[W]e visited the schooner, which is anchored within musket shot of the Washington and there we saw a sight as we never saw before and never wish to see again. The bottom and sides of this vessel are covered with barnacles and sea-grass, while her rigging and sails presented an appearance worthy of the Flying Dutchman, after her fabled cruise….On her deck were grouped amid various goods and arms, the remnant of her Ethiop crew, some decked in the most fantastic manner, in silks and finery, pilfered from the cargo, white others, in a state of nudity, emaciated to mere skeletons, lay coiled upon the decks…. Around the windlass were gathered the three little girls, from eight to thirteen years of age, the very images of health and gladness.

Over the deck were scattered in the most wanton and disorderly profusion, raisins, vermicelli, bread, rice, silk, and cotton goods. In the cabin and hold were the marks of the same wasteful destruction. Her cargo appears to consist of silks, crepes, calicoes, cotton, and fancy goods of various descriptions, glass and hard ware, bridles, saddles, holsters, pictures looking-glasses, books, fruit, olives and olive oil, and other things too numerous to mention--which are now all mixed up in a strange and fantastic medley. On the forward hatch we unconsciously rested our hand on a cold object, which we soon discovered to be a naked corpse, enveloped in a pall of black bombazine. On removing its folds, we beheld the rigid countenance and glazed eye of a poor negro who died last night. His mouth was unclosed and still wore the ghastly expression of his last struggle. Near him like some watching fiend sat the most horrible creature we ever saw in human shape, an object of terror to the very blacks, who said that he was a cannibal. His teeth projected at almost right angles from his mouth, while his eyes had a most range and demoniac expression. We were glad to leave this vessel, as the exhalations from her hold and deck, were like any thing but ‘gales washed over the gardens of Gul.’

4

Abolitionism came relatively late to Lewis Tappan. “Devotional,” “benevolent” and “hardworking” are all words that describe Tappan in his twenties and thirties. Social reformer he was not.

In 1818, Tappan abandoned the Calvinism of his mother for Unitarianism, then a fashionable creed for a socially ambitious merchant. For the next eight years, Tappan enjoyed the typical life of an upper-middle-class New England merchant: he attended theater, danced, drank wine moderately, and read novels. He took his new faith seriously, however, editing the Christian Register, a Unitarian journal, and becoming the first treasurer of the American Unitarian Association.

In the mid-1820’s, America experienced “The Great Second Awakening,” a widespread revival of religion and religious debate. The new Calvanist critique of “infidelism” proclaimed that religion was about things to do, not just things to think about. Tappan took a great interest in the debate. He saw in the Unitarians’ lack of interest in foreign missions and revivals confirmation of the criticism that they lacked the spirit and energy that should reside in true Christians. Tappan made the decision to recommit himself to the Calvanist orthodoxy of his mother. So firm did his conversion to Trinitarianism become that he wrote a tract describing reasons for his switch that sold over 3,000 copies. Growing in Tappan’s bosom was a dynamic, optimistic faith, one that looked forward to the happiness of mankind, the spread of the Christian message from sea to sea, the extinction of heresy, and the birth of a new moral order that reflected the strict ethics of Calvanism.

Tappan became a zealous Christian. He was no theologian; he was a believer. “There is too much theology in the Church now, and too little of the Gospel,” Tappan wrote. He walked the sidewalks and wharves, handing out Bibles and religious tracts. He campaigned for legislation consistent with Calvanist teachings, such as Sunday closing laws. Soon the aggressive campaigns of Tappan and like-minded men and women inspired opposition. But the opposition only seemed to strengthened Tappan’s resolve: “their enmity and clamor are evidence of the righteousness of the cause.” Tappan left the mainstream. He opened up to ideas that most people dismissed as fanatical.

Around 1830, at the age of forty-one, Tappan began to take an interest in the slavery question. A book describing the dramatic efforts of William Wilberforce in England to end the slave trade made a deep impression on him. The fervent abolitionism of men he admired—men like his older brother, Arthur, and the “monitor general” of his sons at Oneida Academy, Theodore Weld—completed his conversion. In the summer of 1833, Tappan resolved to do whatever he could for the abolitionist cause. It turned out to be a lot.

5

The United States Attorney for Connecticut, William S. Holabird, ordered a judicial hearing on the Washington. It was unclear to Holabird whether a crime had been committed, who had committed it, or whether U. S. courts even had jurisdiction. There was also the matter of salvage rights, which were claimed by Captain Green as well as by Gedney and the crew of the Washington. Some estimates placed the value of the Amistad's cargo of wine, saddles, gold, and silk at $40,000 in 1839 dollars, and the slaves had a market value of at least half that much.

On August 29, 1839, three days after the schooner's discovery, District Judge Andrew T. Judson opened a hearing on complaints of murder and piracy filed by Montes and Ruiz. Thirty-nine Africans (of the forty-three who had survived the weeks at sea) attended, including Cinque, who appeared wearing a red flannel shirt, white duck pants, and manacles. He appeared calm and mute, occasionally making a motion with his hand to his throat to suggest a hanging. The three principal witnesses at the hearing--the first mate of the Washington, Montes, and Ruiz--each presented his account of events.

After listening to the testimony, Judge Judson issued his order:

To the Marshal of the District of Connecticut--greeting.

Whereas upon the complaint and information of the United States by William S. Holabird, District Attorney of the United States for said District, against [the Amistads] for the murder of Ramon Ferrer, on the 20th day of June 1839, on the high seas, within the admiralty and maritime jurisdiction of the United States, it was ordered and adjudged by the undersigned that they against whom said information and complaint was made, stand committed to appear before the Circuit Court of the United States for the District of Connecticut, to be holden at Hartford, in said District on the 17th day of September, 1839, to answer to the said crime of murder, as set forth in said information and complaint.

You are therefore commanded to take the said persons, named as above, and charged with said crime, and them safely keep in the jail in New Haven in said District, and then have before the Circuit Court of the United States to be holden at Hartford, in said District, on the 17th day of September A. D. 1839. Hereof fail not, &c. Dated at New

London. August 29, 1839.

ANDREW T. JUDSON,

Judge of the United States for the District of Connecticut.

The grateful Spaniards published a letter expressing gratitude to the American people for their rescue:

NEW LONDON, AUGUST 29, 1839.

The subscribers, Don Jose Ruiz, and Don Pedro Montez, in gratitude for their most unhoped for and providential rescue from the bands of a ruthless gang of African bucaneers and an awful death, would take the means of expressing, in some slight decree, their thankfulness and obligation to Lieut. Com T. R. Gedney, and the officers and crew of the U. S surveying brig Washington, for their decision in seizing the Amistad, and their unremitting kindness and hospitality in providing for their comfort on board their vessel, as well as the means they have taken for the protection of their property.

We also must express our indebtedness to that nation whose flag they so worthily bear, with an assurance that the act will be duly appreciated by our most gracious sovereign, her Majesty the Queen of Spain.

DON JOSE RUIZ,

DON PEDRO MONTEZ.

As the Spaniards thanked America, newspaper editors throughout the East puzzled over the legal questions presented by the slaves’ mutiny and their capture. Even editors unsympathetic to the abolitionist cause, hesitated over pronouncing the Africans guilty. On September 2, 1837, the strongly anti-abolitionist New York Morning Herald told its readers:

We despise the humbug doctrines of the abolitionists and the miserable fanatics who propagate them; but if men will traffic in human flesh, steal men from their homes on the coast of Africa, and sell them like cattle at Cuba, they must not murmur if some of the men stealers get murdered by the unfortunate wretches whom they have wronged and stole. It is certain that the Spanish Government, at Havana, recognizing the right to steal, buy and sell blacks, will, instantly demand the slaves of this government; it is also possible that this government will give up the men, and sell the vessel and cargo for salvage; in that case it is also certain that every one of the male blacks,who rose on the captain will be executed.

The various questions that will arise will be most curious; and the great difficulty will be that the vessel they seized was not a slaver; that they had been sold as merchandize in Cuba, and seized a merchant vessel, and killed a merchant Captain. This alone will constitute them pirates in the fullest sense of the word. Had they merely seized the vessel, without murdering any one, and tried to take her to Africa, our government would have been justified in sending them back to their native homes. Or had they rose on the Captain of the slaver that brought them from Africa, and murdered the Captain and all the crew, by the laws of God and man, the laws of nature and of nations they would have been perfectly justified. But their having been landed at Havana from a slave ship, sold there, and reshipped…will totally alter the aspect of their position and be the main ground of all the arguments for delivering them up and treating them as pirates. It is a hard case, for had they rose on their Captain and his crew two weeks before or been driven into Halifax or Bermuda, they would now have been free was the winds of Heaven. As it is, they will probably be hung.

Let the case be decided as it may, they in all probability, will have to suffer. It is a lamentable state of things.

6

When word of the arrest of the Amistad Africans reached Lewis Tappan in New York, he immediately called a meeting of the city’s leading abolitionists. Tappan recognized that the Amistad story had drama and romance. If developed properly, it could be used to bring to the attention of the public the plight of the hundreds of thousands American slaves. At Tappan’s urging, the group formed a committee of three persons—Tappan, Joshua Levitt and Simon Jocelyn—to aid in the defense of the Africans. The Amistad Committee’s wasted no time in publishing an “Appeal to the Friends of Liberty”:

Thirty-eight fellow men from Africa, after having been piratically kidnapped from their native land, transported across the seas, and subjected to atrocious cruelties, have been thrown upon our shores, and are now incarcerated in jail to await their trial for crimes alleged by their oppressors to have been committed by them. They are ignorant of our language, of the usages of civilized society, and the obligations of Christianity. Under these circumstances, several friends of human rights have met to consult upon the case of these unfortunate men, and have appointed the undersigned a committee to employ interpreters, able counsel, and take all necessary means to secure the rights of the accused. It is intended to employ three legal gentlemen of distinguished abilities, and to incur other needful expenses. The poor prisoners being destitute of clothing, and several having scarcely rags to cover them, immediate steps will be taken to provide what may be necessary. The undersigned, therefore, makes this appeal to the friends of humanity to contribute for the above objects. Donations may be sent to either of the Committee, who will acknowledge the same, and make a public report of their disbursements.

SIMEON JOCELYN. 34 Wall St.

JOSHUA LEAVITT, 143 Nassau St.

LEWIS TAPPAN, 122 Pearl St.

New York, September 4, 1839

Not content to merely collect donations, Tappan set off for New Haven. He met the Africans for the first time on September 6 at the city jail. Tappan described his visit in a letter published in the New York Journal of Commerce:

I arrived here last Friday evening, with three men who are natives of Africa…to act as interpreters in conversing with Joseph Cinquez and his comrades. On going to the jail, the next morning, we found to our great disappointment, that only one of the men, [John Ferry], was able to converse with the prisoners. Most of the prisoners can understand him, although none of them can speak his Geshee dialect. You may imagine the joy manifested by these poor Africans, when they heard one of their own color address them in a friendly manner, and in a language they could comprehend!

The prisoners are in comfortable rooms. They are well clothed in dark-striped cotton trousers…and in striped cotton shirts. The girls are in calico frocks, and have made the little shawls that were given them into turbans. The prisoners eyed the clothes some time, and laughed a good deal among themselves before they put them on.

The four children are apparently from 10 to 12 years of age….They are robust [and] full of hilarity….The sheriff of the county took them to ride in a wagon on Friday. At first their eyes were filled with tears, and they seemed to be afraid, but soon they enjoyed themselves very well, and appeared to be greatly delighted.

Most of the prisoners told the interpreter that they are from Mandingo. The district of Mandingo, in the Senegambia country, is bounded by the Atlantic Ocean, and is directly north of Liberia. Two or three of the men, besides one of the little girls, are natives of Congo, which is on the coast just south of the equator.

Cinquez is about 5 feet 8 inches high, of fine proportions, with a noble air. Indeed, the whole company, although thin in flesh, and generally of slight forms, and limbs, especially, are as good looking and intelligent a body of men as we usually meet with. All are young, and several are quite striplings. The Mandingos are described in books as being a very gentle race, cheerful in their dispositions, inquisitive, credulous, simple hearted, and much given to trading propensities.

After conversing awhile through the interpreter with the men, who are in three different rooms, and with the four children, who are in a room by themselves, we went to the door of the room where Joseph Cinquez is confined. He is with several savage-looking fellows, black and white, who are in jail on various charges…We found Cinquez stretched upon his bedding on the floor, wholly unclothed, with a single blanket partly wrapped around him. He arose at the call of the jailer, rather reluctantly, and came towards us with a good degree of gracefulness and native dignity…[He] conversed very freely, and with much energy of expression and action….

The African prisoners are orderly and peaceable among themselves. Some of them sing well, and appear to be in good spirits and grateful for the kindness shown them. Col. Stanton Pendleton, at whose house I stop, is the jailer, and is kind and attentive to the prisoners. He provides them wholesome food in sufficient quantities, and gives every reasonable indulgence to the numerous visitors, from the neighboring towns and elsewhere, who throng the prison continually to see these interesting strangers from a distant land. Col.[Pendleton] has allowed me to take copies of the warrants of commitment….Shinquau and his comrades are bound over “for murder on the high seas.”

I have read an ingenious and well written article in the Evening Post signed Veto, in which the learned writer presents a pretty full examination of the case of the schooner Amistad… [W]here there exists no treaty stipulation, as there does not at present between the United States and Spain,…this country ought not to surrender persons situated as are Joseph Shinquau and his unfortunate countrymen, who are, by the act of God, thrown upon these shores to find, I trust, that protection and relief of which they had been, probably, forever deprived had it not been for this remarkable and providential interposition.

I remain, very truly, yours,

LEWIS TAPPAN.

P. S. Sabbath evening. The Rev. H. G. Ludlow prayed for the poor Africans this forenoon, very feelingly, at the service in his church…I distributed some religious tracts, in the morning, to the convicts, and attempted to instruct the African prisoners, especially the children. They pronounce words in English very distinctly, and have already nearly the numerals. In showing them some books containing pictures of tropical animals, birds, &c., they seemed much pleased to recognize those with whose appearance they were acquainted, endeavoring to imitate their voices and actions. With suitable instruction these intelligent and docile Africans would soon learn to read and speak our language, and I cannot but hope that some of the benevolent inhabitants of this city will diligently continue to improve the opportunity to impart instruction to these pagans, brought by the providence of God to their very doors.

Towards evening we made a visit to Shinquau, and conversed with him a considerable time. He drew his hand across his throat, as his roommates said he had done frequently before, and asked whether the people here intended to kill him. He was assured that probably no harm would happen to him--that we were his friends--and that he would be sent across the ocean towards the rising sun, home to his friends. His countenance immediately lost the anxious and distressed expression it had before, and beamed with joy….He says he left in Africa both his parents, a wife and three children. Two of the children, he remarked, are a little larger than the African girls who are prisoners, and the other about as large. We endeavored to ascertain what his ideas were about a Supreme Being, if he had any. He said, “God is good.” L. T.

7

The pro-slavery New York Morning Herald answered Tappan’s account with scathing and often viciously racist “letters from Bennett.’ On September 9, the Herald ran the following letter:

The abolitionists are making immense exertions to get the negroes set free; they are raising subscriptions, collecting money, clothing and feeding them; employing the most able counsel, riding over the country, by night and day, to get interpreters who can converse alike in their language and in English; rummaging over musty records, old statutes, treaties and laws, in order to “get a peg to hang a doubt upon” in relation to delivering them up….The canting semi-abolition papers, like the “Journal of Commerce” and the “American” and “Post” are all endeavoring to mis-state, misrepresent, and throw difficulties upon the matter in order to get the black murderers set free. The Southern papers have articles proving the propriety of the surrender.--Meanwhile, the negroes are getting fat and lazy; perfectly indifferent to the disposal to be made of them. They only do two things on the coast of Africa; that is, eat and steal…. Senor Ruiz says that they are all great cowards, and had the captain killed one on the night of the mutiny they would have been subdued instantly, and all have run below. His impression is that they will be sent out to Havana, the ringleaders executed, and the rest given up to him. We shall see. It is a most singular case; we shall follow it up closely; and, unlike the “Journal of Commerce,” we shall do so accurately.

Four days later, "Bennett" predicted that the Amistad affair might figure mightily in the upcoming presidential election:

The "Journal of Commerce" and several other abolition papers, are very busy trying to create excitement out of the Amistad case and captured Africans. The Rev. David Hale, with a hypocritical cast of the eye--not an honest, downright squint like mine--is publishing the correspondence of Lewis Tappan & Co., who intend, out of this case, to revive the dying embers of abolition in the north….. This day we renew the publication of our correspondence from New Haven, and at the holding of the U. S. Court, beginning on the 17th instant, we shall also have our reporters in constant attendance. Already this strange affair bids fair to excite a stronger feeling throughout the Union, than any event that has happened in a long time. Whatever disposition be made of these Africans, the laws and treaties between nations ought to govern its course, in exclusion of those mischievous appeals to the passions of the mob of pious or profane loafers. We should not be surprised even, if the Amistad case entered deeply into the next election. Every thing about it looks black enough for a squall. Get out your great coats and umbrellas--we know not the moment the clouds will pour down, or the wind may blow.

On October 4, "Bennett" published a revealing--if highly slanted--account of New England's fascination with the Amistad Africans:

A change has passed over the entire spirit of the existence of the negroes since their confinement at Hartford. Their animal spirits are greater than ever; they eat more, drink more, chatter more, gambol more, and turn more somersets than ever. In short, they are as merry as crickets, and as satisfied as pigs in clover. The excitement that is manifested by almost every one in relation to their disposition and their present condition, communicates itself to them. They are tickled half to death at the idea of having so much to eat without any labor to obtain it; so many persons to visit them; so many presents made to them; so much time to sun themselves; to roll, and tumble, and turn somersets.

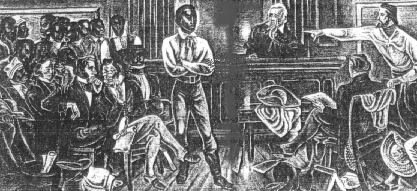

Accompanying this letter, you will receive a drawing made by a distinguished artist from New York, called Peter Quaint, which is a faithful representation of the scenes generally taking place here. On the left hand is Lewis Tappan, with his white hat, attended by another abolitionist, looking at Cinguez kissing a pretty young girl, who was handed up to him by her sympathetic mother. Near the mother is the celebrated phrenologist, Mr. Pierce, who has been forming a vocabulary of their language, hereunto annexed. In the center of the prison group is Garrah, turning a somerset before the Africans and white company --- and below, in the foreground, are two negroes scratching themselves, for it is well known that many of them have the itch. Away to the right is the fashionable, pious, learned, and gay people of Connecticut, precisely as they appeared during these amusing scenes in Hartford prison, receiving lectures and instructions in African philosophy and civilization.

These blacks have created a greater excitement in Connecticut than any event that has occurred there since the close of the last century. Every kind of engine is set in motion to create a feeling of sympathy and an excitement in their favor; the parsons preach about them, the men talk about them, the ladies give tea parties and discuss their chivalry, heroism, sufferings; thews and sinews, over their souchong; pious young women get up in prayer meetings and pray for them; scouts are sent round the country to hunt up all the negroes that can speak any kind of African dialect; interpreters by dozens arrive daily at Hartford; grammars and spelling books and primers without number, in all sorts of unknown tongues, are sought for and secured. [It has been a] few weeks since Lewis Tappan arrived in Hartford, accompanied by his black tail; consisting of a great number of negroes of all ages and sizes, and colors, and speaking all languages from the Monshee down to the Mandingo. The appearance of this patron of pious negroes was exceedingly singular, as he paraded the streets of Hartford with a dozen negroes forming a black tail; first came a dark Congo negro, then one from further north not quite as black; then a very dark mulatto nearly black, then a very brown fellow, then a copper colored negro, then one a brownish yellow, then a dark yellow, then a light yellow, then a mustee, and then one almost as white as himself and much better looking.

The black fellows in confinement are astonished at all these singular movements, and begin to think, from the number of negroes brought to talk and jabber with them, that the blacks are the principle men in this country. They laugh heartily at all the movements of the whites, and consider them poor loafers, with ungraceful movements, and very much to be pitied because they are totally unable to turn a somerset. This is the ne plus ultra of accomplishments and refinements with them. If a man cannot turn a somerset they think very little of him in the way of civilization. They listen to what Lewis Tappan and the others have to say; and although Cinguez understands scarce a word that is said, and is conversed with often by signs; he replies merely by taking Lewis Tappan and his friends into the middle of the floor, and by signs asking them to turn a somerset. When he finds they are unable to oblige him in this particular, he throws a somerset himself by way of a lesson to them, laughs heartily, tries to turn up his flat nose, and walks off to his comrades, evincing the greatest contempt for the white chiefs who can't throw a somerset. In short, to such an extent do they carry this tumbling propensity, that it forms part of their religion….

At new Haven ladies were not allowed to visit the negroes generally;but at Hartford all who wish to enter are admitted. Before they left New Haven a very beautiful single white lady called on Captain Pendleton, the keeper of the prison there, and expressed a desire to see Cinguez, the chief and hero of this affair, as she termed him, as she wished to have a private interview with him, and converse with him alone. The keeper very politely told her that she could not be admitted to see him alone in his cell, but that he had a private room in his own house, where she could interview with him alone, as long as she liked. This she declined; but this is a faint specimen of the enthusiasm that exists among the young people of Connecticut in relation to them, particularly the women. It is a species of hallucination. They have invested in this affair, with all the romance of an eastern fairy tale, and they consider the black fellows as worthy of as much honor as the colored Moorish Knights of old; and if they get clear, it is probable some Yankees will pick them up in detail, and take them around the country to show them by way of a speculation. The poor blacks themselves are utterly astonished at the prodigious sensation they have created; it is the only topic touched upon in conversation, in the streets, the bar room, the ball room, the boudoir, the bed room, the kitchen, the parlor and the pulpit. And the negroes show their astonishment by eating an additional quantity of rice and throwing a few extra somersets to assist digestion.

The scenes that daily take place here in the prison here in consequence of this excited feeling, are ludicrous in the extreme. Parsons go to preach to them, philosophers to experiment on them, professors to pick up a knowledge of their language, phrenologists to feel their heads, and young ladies to look and laugh at them.

8

Lewis Tappan's reports, read by a very different audience, brought even more attention to Cinque. The leader of the Amistad mutiny was fast becoming a romantic figure. Tappan described an “examination” Cinque and another African named Bowle. Present with Tappan for the interview were Roger S. Baldwin (a well-respected lawyer retained by the Committee to represent the Africans), Josiah Gibbs (a Yale professor of linquistics), and an African interpreter:

We endeavored to impress upon their minds, in the first place, that we were their friends, and that they must speak the truth. Both of them appeared to have some idea of a good Spirit, and also of an evil Spirit. They said "God is good," and if they told lies, the evil Spirit would take them somewhere, they did not know where. Jingua had been asked if he did not know that God would punish him if he did not speak the truth, and he replied "yes," and added in his own language--"me tell no lie; me tell the truth." Jingua said he knew that if they do good they will go to God, and if they do bad the evil one will get them. On being asked where God was, he pointed upward.

Jingua repeated that he left his father, mother, wife and three children in Africa, and Bowle said he left his mother, three brothers and two sisters and his native place, Badebou….They stated that they had been in battles, in their own country, using muskets, but had never been kidnappers. I would never take any advantage of any one, said Jingua, but would always defend myself. Bowle said his oldest brother was in debt, and they sold him, to pay it. They have no money there, said he, and trade away to the Spaniards, for powder and guns. Bowle said there was great slavery in Gallinas. (This is the place where Don Blanco, the great slave trader, pursues his hellish business.) They stated that they were brought down the country to the seacoast, and were chained when put on board the slaver, which was a brig. It was crowded with slaves, there being 200 men, 300 women, and "plenty of children." Jingua here got down on the floor, to show us how they were stowed on board, then moved about on his knees, and as he rose put his hand of the top of his head, to indicate how low the deck was. They said their sufferings were great on the passage, and several of their number had died.

They stated that they were nearly two months going to Havana….

Jingua appeared to be highly gratified to be taken from his cell, and to have the opportunity to look at the public buildings and the beautiful park, for the first time, from the windows of the chamber. When he entered the room his bearing was like another Othello. He seemed, at first, under some apprehension, but, after a while, appeared to be well aware that he was interrogated by persons friendly to him. He told his story in an animated manner…Occasionally he would shake hands with the interpreter, and laugh very heartily. When removed from the chamber, he was allowed to visit his countrymen. They shouted for joy, on seeing him, called him 'massa,' and every one of them immediately, of their own accord, gave into his hands all the money, &c. they had received from the visitors. He took it, but before he reached his cell, he suddenly handed the money to his brother, who is one of the prisoners, thinking probably, and justly enough, too, that it would not be very safe when he should return to the convicts with whom he is incarcerated.

One of the men attached to the prison was the occasion of great amusement on the part of the prisoners, as well as the spectators, by taking a large lump of ice to show these strangers from the tropics. They all handled it in turn, but each one, after holding it a moment, screamed out as if their hands had been burned, and entreated the man to take it out of their hands. They would then look at their hands to see of the skin was off, examine very closely the novelty, then taste of the water on their hands, then touch the ice with their tongues, or take a small piece into their mouths. As the ice was passed around, they laughed immoderately at the momentary agony of their comrades.

One of the physicians of the city, who happened to be at the prison, and who expressed his surprise to find that the prisoners, as a body, were all well formed, and appeared quite as intelligent as an equal number of of colored persons in New Haven, or any other part of the country, took hold of the head of one of them, to examine it phrenologically, when the young man burst into a rough laugh saying, "it is a very poor head." Some of them are not only cheerful, but merry, and show much agility, wit and shrewdness. Jingua is generally grave and thoughtful, but his countenance is occasionally light up, when the expression is very prepossessing, indicating much natural benevolence of heart.

The curiosity to see the prisoners appears to be unabated. Most of the visitors express much sympathy with these much abused strangers, and utter sentiments of strong indignation against those who have torn them from their native land, or meditated their enslavement. But there are a few persons, even in Connecticut, who unblushingly aver that these Africans are not men; that it is right to enslave them, and that they will undoubtedly be given up by our government. It remains to be seen whether a grand jury can be found in the land of Roger Sherman to find a bill of indictment against these victims of cupidity, or a petty jury to find them guilty of crime, or whether the judge will pronounce that they have violated American Law, or the Executive attempt to surrender them to a foreign owner. The wise and good throughout Christendom will watch our proceedings; and the result, be it what it may, will materially affect the character of this nation, both with contemporaries and posterity….

Very truly yours,

LEWIS TAPPAN.

9

The usually quiet town of Hartford took on a carnival atmosphere as the time of trial approached. Lawyers, reporters, and interested visitors from Boston to New York filled hotel rooms, roamed the public streets, and picnicked on the lawn in front of the two-story brick courthouse. Vendors hawked engravings of Cinque or the schooner Amistad. People gathered excitedly along the banks of the Connecticut River to welcome the arrival of boats bearing principal players in the courtroom drama: a paddle steamboat carrying Senors Ruiz and Montes and Lieutenant Gedney, a canal boat carrying the Africans, shivering in the cool September air.

In a courtroom “filled to suffocation” Lewis Tappan sat on a bench next to the little girls Montez claimed as his slaves. The girls sobbed loudly as they sat wrapped in white blankets. Tappan took the hand of the girl next to him. Colonel Pendleton, their New Haven jailer, gave them apples in an effort to cheer them up.

The great excitement surrounding the case pleased Tappan and his fellow abolitionists. In the weeks preceding the trial, 4,000 persons a day had paid twelve cents each to catch a glimpse of the Africans. All the leading New York papers were giving the trial extensive coverage. No paper attached more significance to the case than the abolitionist weekly, the Emancipator. An editorial in the Emancipator’s trial day edition proclaimed that “God has ordered [the African to our shores] to hasten the overthrow of slavery.”

The young African girls sitting next to Tappan might have understood that the courtroom activity was about them, but they could hardly understand why. The abolitionists and their lawyers had asked the Circuit Court of Connecticut for a writ of habeas corpus that would order the release of the three girls from custody. They had chosen to limit their initial effort to the girls for two reasons. First, they wanted to keep the focus on the girls, who played no role in the mutiny and who could be expected to generate public sympathy for the abolitionist cause. If the writ were to be granted for them, it would be strong precedent for other Africans. Second, they recognized that it was almost beyond argument that the girls--given their tender age and the fact that none spoke a word of Spanish--were Africans, and therefore a judge would have a difficult time concluding that they legally had been sold as slaves.

Two federal judges and a grand jury assembled in Hartford to try to untangle what had become a legal knot of unprecedented dimensions. In addition to the habeas corpus petition of the abolitionists, the case presented issues of criminal law, property law, admiralty law, and jurisdiction. As lawyers laid out their arguments in the courtroom, a grand jury meeting in another room in the courthouse debated the testimony of Ruiz, Montes, and the cabin boy Antonio relating to the mutiny and killing of the Amistad’s captain and cook. Every so often the grand jury would shuffle into the courtroom to ask Circuit Judge Smith Thompson for guidance on their deliberations. Attorneys for the Spaniards pressed their demand that the Africans, as slaves lawfully purchased in a nation where slaveholding is legal, be returned to them as their property. The lawyer of Captain Henry Green, who first met the Africans on a Long Island beach, argued that Green was entitled to salvage—a percentage of the value of the Amistad and its cargo, including the slaves. Another attorney argued a similar claim for Lieutenant Gedney. Finally, U. S. District Attorney William Holabird, citing a 1795 Treaty, contended that the Africans should be placed under the control of President Van Buren.

Lewis Tappan published his account of the complicated legal maneuverings in the New York Commercial Advertiser . Not surprisingly, Tappan’s characterizations of the arguments reflected his abolitionist bias. He described the arguments of abolitionist attorneys Roger Baldwin and Seth Staples as “powerful,” the argument of District Attorney Holabird as “lame.” The Spaniard’s argument, however, he credited as being “ingenious.” Tappan wrote that Staple’s argument for release of the girls demonstrated the “noble and eloquent character of the writ.” Baldwin’s argument received his commendation for “bestowing a very severe castigation on the Spaniards.”

The trial story read very differently in the pro-slavery New York Herald. The Herald saw the trial as involving “principles of the greatest magnitude to the country.” It digested the case for its readers as primarily “a struggle between the government and the Abolitionists for possession of the Africans: The U. S. government wants to get them to deliver to the Spanish authorities—and Lewis Tappan and Co. want to get them, to make saints of them.” Despite its slant on the proceedings, the Herald conceded that the abolitionists had made a strong case. Roger Baldwin, the paper said, had put the African’s case in the “strongest possible light” and had “closed with an effective appeal to the sympathies of the court.”

After all the grand jurors, attorneys, deponents, and judges in Hartford had done their work, what came out was half victory, half defeat for the Africans and their abolitionist defenders. Judge Smith Thompson, accepting the grand jury’s facts concerning the mutiny, announced that the court was without jurisdiction to hear any criminal charges against the mutineers of the Amistad. The crime, if there was one, was committed against Spanish citizens on a Spanish boat in Spanish waters. Jurisdiction to hear a criminal case could only rest in Spain or her possessions. There would be no criminal prosecution in his courtroom. Smith, however, refused to issue a writ ordering the Africans’ immediate release, despite having great sympathy for the request. Smith, one of only two justices on the United States Supreme Court known to oppose slavery, explained his decision: “However abhorrent it may be to our feelings, however desirable that every human being should be set at liberty, we cannot be governed by our feelings, but only by the law.” The law, Smith announced, convinced him that the district court had the right to keep the Africans in its custody until it decided whether any of the several claimants held a property right in them as slaves. The district court would meet in November to resolve the matter of property.

The New York Herald gleefully reported that abolitionists were “half frantic” at Thompson’s refusal to release the Africans: “It would do your heart good to see the abolitionists since the decision of Judge Thompson. Poor devils! They are chagrined beyond measure. Their faces have increased so much in longitude that every barber in the place charges double price for shaving them.” With cruel sarcasm, the Herald described the abolitionists’ disappointment in being denied their hoped-for division of the Africans: William Lloyd Garrison would not get the cannibal he hoped to lease to the Zoological Institute to pay down the debts of his abolitionist paper, The Liberator. Reverend Henry Ludlow would not be able “to fit for holy orders” the murderer of Captain Ferrar. Lewis Tappan would not be allotted Kenyee, the African girl best “calculated to aid in the mixture of milk and molasses” (a reference to Tappan’s much-ridiculed hope that inter-marriage might someday turn all Americans “copper-colored.”)

10

Yesterday we had Ruiz and Montez, the two Spaniards of the Amistad arrested, and not choosing to give bail they are now in prison. They are arrested at the suits of some of the captured Africans for assault & battery, and false imprisonment. The pro-slavery press, and the Southern slaveholders now here, are greatly exasperated & I doubt not it will exasperate the tyrants & their abettors throughout the country. But we shall try the question in our courts, & see if a man, although he is black, cannot have justice done him here.

--Lewis Tappan (letter to Joseph Sturge, October 19, 1839)

Lewis Tappan believed that the only enemy of abolition was apathy. Whatever got people thinking and talking about slavery advanced the noble cause. With the start of the civil trial in Hartford a month away, Tappan considered strategies for keeping the Amistad controversy in the public spotlight. What action would be more certain to create a furor than initiating a suit against the Spanish slaveowners for assault and false imprisonment? The pro-slavery press would be practically apoplectic. He saw other benefits from a civil suit as well. The suit could be filed in New York (a free state) rather than in Connecticut (where slavery was still legal). The suit would force the court to choose between finding the Africans slaves without recourse against their masters or free persons with legal rights. Finally, it would provide an opportunity to refute the narrative of Ruiz and Montes—“a lame account” in Tappan’s estimation. Tappan knew the chances for success on the merits of the suit small, but the other advantages justified the action. He filed suit.

On the morning of October 17, Lewis Tappan carried to the office of the sheriff in New York City two writs, one for each of the Spaniards, calling on them to answer charges of assault and false imprisonment brought by Cinque and Fulah, “Africans of the Mendi tribe.” The writs demanded that Montes and Ruiz each pay $2000 for their mistreatment of the plaintiffs. Deputy Sheriff Josiah Kreene accepted the writs and set out with Tappan to make the requested arrests.

The two men found the Spaniards in their hotel. The New York Herald of October 18 offered an account of the arrests that nearly screamed with outrage:

Lewis Tappan, like his prototype, who first kissed his master and then sold him for thirty pieces of silver, went up to Mr. Ruiz and said to him, with a half-benevolent, half-malignant smile—“How do you do, Mr. Ruiz?” Then turning to the officer, he said, “This is your man—take him”….“I have no bail—I cannot get bail at present,” said Mr. Ruiz. “Then you’ll have to go to prison,” said Lewis, with a chuckle. The same process took place with Senor Montez, who is almost too sick and weak to get out of bed…If ever deeper and intense malignity could be shown to the world than Lewis Tappan has now exemplified we should like to hear of it. For the sake of human nature, it is to be hoped that his conscience will not make him hang himself on the next tree; because it he waits till he gets a little leaner, there will be less danger of his breaking the rope.

Pro-slavery editorialists fumed at what they variously called a “ruse” or “subornation of perjury.” The Charleston Courier scoffed at the notion that two Africans would choose to pursue a legal action: “The Savages, in whose names these suits are instituted, are of course ignorant of the whole matter. A lifetime would not suffice to make them comprehend it.” The New York Herald saw the suit as “a ruse to prevent [Ruiz and Montes] from proceeding to Havana to procure evidence of their right to the negroes.” The Richmond Enquirer proposed placing Tappan in a “lunatic asylum” and asked whether he planned to “make the blacks our masters.”

The new Spanish minister to the United States, Pedro Argaiz, angrily protested the arrest of the two Spanish citizens in a letter to pro-slavery Secretary of State John Forsyth. He blasted the abolitionists who shamelessly supported “notorious murderers” and “savages.” “When, in what country, at what period of history,” Argaiz asked, “has a slave been considered as enjoying civil rights?” Argaiz requested that the Van Buren Administration use “the law of habeas corpus” to “liberate” Montes and Ruiz. Such a response, Argaiz suggested, would calm “the disquiet which this news may occasion in the mind of her Majesty,” young Queen Isabella.

In an atmosphere of great excitement, Judge Inglis of the New York Court of Common Pleas opened preliminary hearings in the cases of Fulah vs. Ruiz and Cinque vs Montes. John Purroy, the young, hot-tempered attorney for the defendants read affidavits of Ruiz and Montes in which they claimed not to know that their slaves—purchased lawfully, they insisted--were Africans. The Spaniards in their affidavits asserted that they fed the slaves of the Amistad well and never whipped or manacled them. Purroy glared at Tappan, who was present at the hearing, and accused him of instituting the suits. He called him “Judas” and an “archfiend.” The plaintiffs he called “pirates” and “murderers.” Theodore Sedgewick, hired by Tappan to represent the Africans, responded with affidavits of his own, including one from Lewis Tappan describing his visit to the plaintiffs’ jail cells in New Haven and the grounds for his belief that they were Africans. Sedgewick asserted that Ruiz and Montes must have known their non-Spanish speaking slaves to be Africans. He read from the 1817 Treaty between England and Spain which, he contended, showed the Africans to be free persons, not the lawful property of the two Spaniards. A jury, Sedgewick, contended must finally decide the issue of his clients’ status as either slaves or free persons entitled to redress for their injuries. Sedgewick’s co-counsel, Seth Staples, lamented the “spirit of slavery” whose “direful influence” had “debauched” the court. Judge Inglis announced that he would take the papers prepared by the lawyers, research the law, and give a decision in a day or two.

On October 31, Judge Inglis delivered his decision. The trial could go on, he said. In the matter of the application of Ruiz and Montes to be freed without bail, Inglis announced a split decision. He granted the application of Montes who, he said, was not implicated in any assault. On the other hand, Ruiz, who was alleged to be present when the cook of the Amistad struck Cinque, would be retained on bail of $250. Spanish minister Argaiz observed the court proceedings with growing incredulity. Was there no federal power, he wondered, to “interpose its authority to put down the irregularity of these proceedings?” The Emanicipator celebrated its achievement of a “great point”: the right of blacks to bring civil suits. Southern editorialists fretted that the decision might encourage fugitive slaves to haul their former owners into northern courts where they might be forced to pay damages by a “prejudiced and fanatical jury.”

Montes, not unexpectedly, left the country for Cuba. Ruiz, however, refused for four months to post bail and remained in the New York City jail in relaxed confinement. Tappan called Ruiz’s decision to forego bail a “ruse to excite sympathy, and prejudice the community against the Africans and their defenders.” If that was indeed the goal of Ruiz, his efforts were successful. The Ruiz-Montes controversy caused sympathy for the captive Africans to evaporate. “TAPPANISM,” as it was called by the New Orleans Picayune, again came under heavy attack. At another level, Tappan’s risky strategy may have paid off. The civil suit focused such attention on the judicial process that it made executive intervention in the Amistad case by the Van Buren Administration politically risky. If there was one thing President Martin Van Buren cared about, it was getting re-elected.

11

The schooner Texas arrived in New York harbor from Havana on November 5, bearing a cargo of molasses and one passenger, Dr. Richard Robert Madden. Madden carried with him a letter bearing the address of Lewis Tappan’s office. After asking directions, he headed toward the Tappan warehouse in Hanover Square.

As the British superintendent of liberated Africans in Cuba, Madden sought to protect freed Africans from becoming slaves in all but name. It was not an easy job. Under the England-Spain Treaty, emancipated slaves were to be turned over by the British to Cuban officials, who could put them to work as free laborers for seven years before the Africans gained full freedom. Cuban officials sold the emancipated blacks to planters who worked them harder than they did their regular slaves, knowing that at the end of the seven years they would be of no further use to them. Many Africans did not last the seven years. Madden’s work made him intimately acquainted with all aspects of the Cuban slave trade, from the importation business of the notorious Martinez and Company to the issuance by Cuban officials of passports fraudulently labeling Africans as “Ladinos.” Madden, a fervent abolitionist, had decided to volunteer his testimony in support of the Amistads. No evidence in the trial would be more critical.

Tappan shared with his British guest his concerns about the upcoming proceedings that would determine the fate of the Africans. His biggest worry was Andrew T. Judson, the District Judge for Connecticut. Tappan and his brother Arthur knew Judson well. A few years earlier the Tappans and Judson had been on opposite sides of a controversy involving a young white woman named Prudence Crandall. Crandall had opened an all-black girls academy in rural Connecticut near the home of Judson, then a town selectmen. Judson led the drive to rid his state of Crandall and her school. Judson rallied townspeople to his cause claiming that the school would become “an auxiliary in the work of immediate abolition” and soon New England would become “the Liberia of North America.” Townspeople passed a resolution condemning Crandall for promulgating the “disgusting doctrines of amalgamation.” Ultimately Judson and his followers succeeded in pressuring the state assembly to enact the “Connecticut Black Law,” which provided for the expulsion from private schools of non-resident blacks. Judson prosecuted Crandall, the first defendant under the new law. The Tappans financed her defense. Judson told the jury, that Crandall’s “professed object is to educate the blacks” but that her real goal was to place the African race “on the footing of perfect equality with Americans.” The lawyers hired by the Tappans made an eloquent argument—years ahead of its time--that the law violated the constitutional rights of blacks. Judson got his conviction. When Connecticut’s supreme court overturned Crandall’s conviction on a technicality, a mob set fire to her house. Crandall gave up her school.

Before they would face Judge Judson, Tappan thought it important that Madden meet the Africans on whose behalf he would testify. The two men set out for the jail in New Haven, where Tappan introduced the Africans to Madden.

From New Haven, Madden left by coach for Hartford, arriving the day before the trial began in Judge Judson’s courtroom. Madden sat on the sidelines during the opening day as attorneys skirmished over whether the admiralty claims belonged in Judson’s court or a court in New York, the state where the Africans first landed--and where the abolitionists would now like to be. After several hours of testimony concerning the exact location of the Amistad at the point of capture—was it in New York waters or on the “high seas”?—Judson ruled that the case belonged in his court. Realizing that they were stuck with Judge Judson, the abolitionists argued their main point: that the blacks were kidnapped Africans, not slaves who could be claimed as property or salvage. On this issue the abolitionists intended to rely heavily on the testimony of Madden, but counted also on James Covey, their African-born interpreter. Unfortunately, Covey was seriously ill and did not make it to Hartford.

Could the trial be postponed without sacrificing Madden’s crucial testimony? Judson consented to allow a deposition of Madden that could be used when the trial reconvened in January. On the afternoon of November 20 in the chambers of Judge Judson, before a group of interested attorneys and spectators, Madden described the system of fraud, corruption, and cruelty that accompanied the buying and selling of human beings in Cuba. Madden recounted a visit to the barracoon where the Amistad Africans had been bought. When the “major domo” of the barracoon said of the Africans’upcoming trial in the United States, “Que lastima!” (“What a pity!”), Madden expressed surprise at the Cuban’s sympathy for their plight. The major domo explained that the Africans surely would be executed and it was a shame for Ruiz and Montes to lose “so many valuable [slaves].” Madden’s convincing and impressive performance confirmed everything the abolitionists had said about slave trafficking in Cuba.

Judson announced that the trial would reconvene in New Haven in January.

12

The vessel destined to convey the negroes of the Amistad to Cuba, to be ordered to anchor off the port of New Haven, Connecticut, as early as the 10th of January next, and be in readiness to receive said negroes from the Marshal of the United States, and proceed with them to Havana, under instructions hereafter transmitted.

Lieutenants Gedney and Meade to be ordered to hold themselves in readiness to proceed in the same vessel, for the purpose of affording their testimony in any proceedings that may be ordered by the authorities of Cuba in this matter.

On the night of January 9, 1840, the naval schooner USS Grampus slipped into New Haven harbor. The Van Buren Administration had diverted the Grampus from its anti-slavery patrol on the African coast to Connecticut for an important mission. Lieutenant John S. Paine, the ship’s commander, and Norris Willcox, the U.S. Marshall at the trial then in progress before Judge Andrew Judson, had top secret orders. President Van Buren’s order called upon Willcox to take possession of the Amistad Africans should--as expected--Judson authorize their transport to Cuba to stand trial for piracy and murder. The orders called for Willcox to hustle the blacks onto the Grampus for immediate departure for Cuba “unless an appeal shall actually have been imposed.” Van Buren was anxious to placate Spain which, its minister said, “did not demand delivery of slaves but of assassins.”

Van Buren’s order was an attempted subversion of the judicial process—nothing short of a blatant interference with the guarantee of due process set forth in the Constitution. Most abolitionists, noting the presence of the schooner in the harbor, did not imagine its nefarious purpose. Lewis Tappan did. He never underestimated the deviousness of slavery’s defenders and protectors. Tappan, according to some historians, developed a secret plan of his own. Rumors circulated that he and other abolitionists procured a schooner which they hoped to use to whisk the Africans to Canada, should things turn out poorly in the New Haven courtroom.

Spectators, lawyers, and parties squeezed into every available seat in Judge Judson’s courtroom. Yale Law School and Yale Divinity students lucky enough to have gotten seats refused to leave the courtroom, even during long recesses, for fear of losing their places. Nearly a dozen lawyers representing the Africans, the Spaniards, the salvage claimants, and the U. S. government, huddled at their desks. Judson, serious and austere, presided from the bench. Lewis Tappan, sitting near the Africans, gazed at the remarkable scene that he--more than anyone--had produced.

Roger Baldwin won loud cheers from a mostly pro-African crowd for an eloquent defense of liberty. Irritated, Judge Judson rapped for order. A parade of abolitionist witnesses offered evidence of the Negroes’ African origins. Then the moment that the crowd eagerly anticipated arrived. Cinque, wrapped in a blanket, rose from his chair and walked to the witness stand accompanied by James Covey, the Mende interpreter. With “breathless attention,” courtroom spectators listened as Cinque told the story of an eventful five months beginning with his being kidnapped by four Africans while working on a road near the home of his wife and three children and ending with his arrival and capture on Long Island. Cinque sat on the courtroom floor to show how he was manacled, hands and feet together, on the Middle Passage voyage of the Tecora.

No trial is non-stop entertainment. Mixed with the dramatic testimony of Africans and Antonio, the Cuban cabin boy, were arguments and testimony that only an admiralty lawyer could enjoy. The trial would decide not only the fate of the Africans, but of the Amistad and its cargo as well. On Saturday, January 11, the court adjourned. Judson announced that he hoped to have his decision ready by Monday.

On a cold Monday morning, with his face gaunt and tense, Judge Judson announced his several-part decision to a filled courtroom. He began with his resolution of the salvage claims. He accepted Gedney’s claim: the Lieutenant rendered a valuable service in seizing the Amistad and preventing the likely loss of its remaining cargo. Judson awarded one-third of the value of the ship and its non-human cargo to Gedney. The ship and its cargo—subject to Gedney’s salvage lien—should be restored to the Spanish government. But, ruled Judson, there could be no salvage right in the Africans. Neither were they the property of Ruiz and Montes. The blacks “were born free and ever since have been and still of right are free and not slaves.” They would not be returned to Cuba to stand trial as accused murderers and pirates. They revolted, Judson concluded, out of a natural “desire of winning their liberty and returning to their families.” Judson continued, “Cinque and Grabeau [another African who testified] shall not sigh for Africa in vain. Bloody as may be their hands, they shall yet embrace their kindred.” Judson ordered that the Africans be placed under the control of the Executive and returned to Africa.

Tappan saw Judson’s decision as an attempt to “steer between” slavery and unequivocal freedom. It was a compromise, but one that he and the abolitionists could live with. As much as he might have wished it would be so, Tappan could not have expected any federal district judge—least of all Andrew T. Judson—to issue a decision repudiating the institution of slavery. All in all, it was a very good decision. Tappan hurried to the New Haven jail to tell the Africans the news. Upon hearing Tappan’s words, the young Negroes fell on their knees before him, then leaped and shouted in joy. When the tumult subsided, the Rev. Henry Ludlow led a prayer of thanksgiving. Tappan observed that the Africans “followed him audibly, and with apparent devoutness.”

Meanwhile, the USS Grampus sailed out of the harbor and headed south.

13

Circuit Judge Thompson affirmed Judge Judson’s decision. The Administration again appealed, this time to the United States Supreme Court, where five of the nine justices were southerners who either owned or had owned slaves.