by Douglas O. Linder (2019)

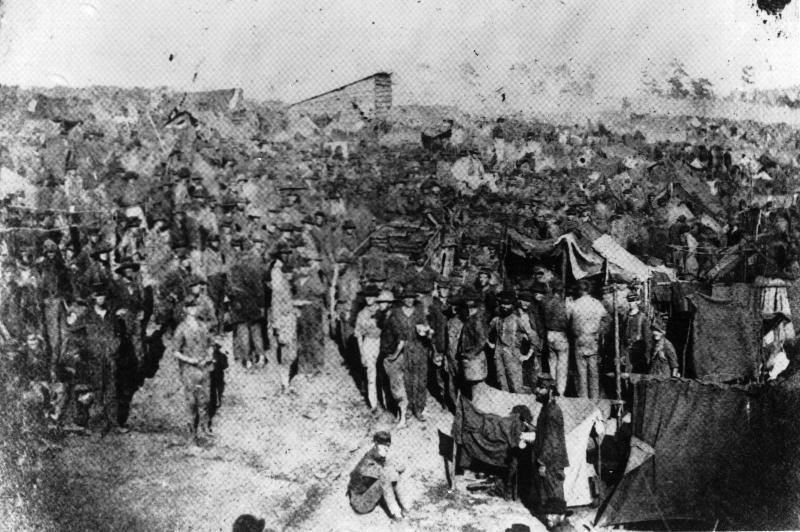

Andersonville, August 1864 (photo by A. J. Riddle)

This work of death seems to have been the saturnalia of enjoyment for [Wirz], who amid these savage orgies evidenced such exultation and mingled with them such nameless blasphemy and ribald jests, as at times to exhibit him rather as a demon than a man. (From the Opinion of Judge Advocate General Holt in the Wirz Case, as sent to President Andrew Johnson.)

It was a horrific place. The deadliest place, in fact, of the Civil War. Camp Sumter, or Andersonville as it has come to be called, housed 32,000 Union prisoners at its most crowded, and they died at an alarming rate. In August of 1864, 2,997 prisoners died at Andersonville. On one August day alone, 207 men breathed their last.

Most died from disease, lack of medicine, unsanitary conditions, or starvation. But many died from bullets. Some were ripped apart by prison dogs. It was a hard place in a hard time--but with proper food, clothing, and clean water, most of the prisoners likely could have survived the war.

The commandant of the stockade, Henry Wirz, could not be blamed for every casualty at Andersonville. Some Wirz apologists have even suggested he deserves no blame at all, perhaps even a statue honoring his service. But the trial of Henry Wirz left little doubt that he was a cruel man who threatened and berated prisoners. Moreover, the record shows that with little provocation, Wirz sometimes ordered prisoners shot, sometimes shot them himself, or left it to his hounds to do the job.

Wirz's defenders offer a variety of arguments: "War is hell" (it is) and "prison camps never a bed of roses" (true enough); "He did the best he could in bad circumstances" (he did make some efforts to improve conditions); "Nobody's perfect" (but some fall much further from perfection than others). Wirz's prosecutor called the commandant of Andersonville "more a demon than a man." Wirz's defenders see most of the charges against him as baseless and view him a scapegoat for a tragedy that was largely out of his control. A demon or a martyr-hero? As is often the case, the truth lies somewhere in between.

Background

The tragedy of Andersonville was set in motion by the decision, in late October of 1863, of Secretary of War Edwin Stanton to halt the exchange of prisoners of war. Stanton gave as his reasons Confederate violation of the agreement for exchanging prisoners, as well as Confederate mistreatment of African-American soldiers and their white officers. Ending the exchange program also had military advantages. The Union had a manpower advantage and, as General Grant observed, why release “an active soldier [who will fight] against us?”

The following month, the Confederate Secretary of War, James Seddon, ordered a meeting to select a place in Georgia to hold a new Confederate prisoner of war camp. A site near the town of Andersonville was chosen, based on its proximity to the railroad and other resources such as timber and water. By the end of February 1864, a 16.5 acre, 20-foot high pine log stockade in the shape of a parallelogram was completed. Guardposts were stationed along the top. A low railing ran about 15 to 20 feet inside the stockade and parallel to the walls. The railing marked the “deadline.” Any prisoner who crossed the deadline would be shot without warning.

Captain Henry Wirz

In late March, Captain Heinrich (Henry) Wirz took charge at prison commandant, the person with direct charge over the inmates. Wirz was born in Zurich, Switzerland and was a doctor by profession. When war broke out in 1861, Wirz left his practice in Louisiana and volunteered. Shot in the right shoulder and arm in the Battle of Seven Pines, Wirz was reassigned to command a prison camp in Virginia.

When Wirz arrived at Camp Sumter, the stockade held 8,000 Union soldiers, and the soldiers kept coming. The soldiers came from every state in the Union and included African-Americans and Native-Americans. Conditions in the stockade were filthy the day Wirz arrived—and things only got worse from then.

Wirz made modest efforts to improve the situation. When the waste of thousands of prisoners turned the stream running through the camp into a maggot-filled quagmire, Wirz attempted to build dams and divide the stream into separate areas for drinking, bathing, and sanitation. But with a lack of material and engineering expertise, the efforts failed. He also made some efforts to

locate needed supplies for the camp such as medicine, food, and clothing. These efforts were largely futile owing to deteriorating conditions in the South. Wirz did order an enlargement of the stockade by ten acres to better accommodate the flood of incoming prisoners, but the prison remained overcrowded by any reasonable measure. But Andersonville remained a filthy, disease-ridden, hellish place.

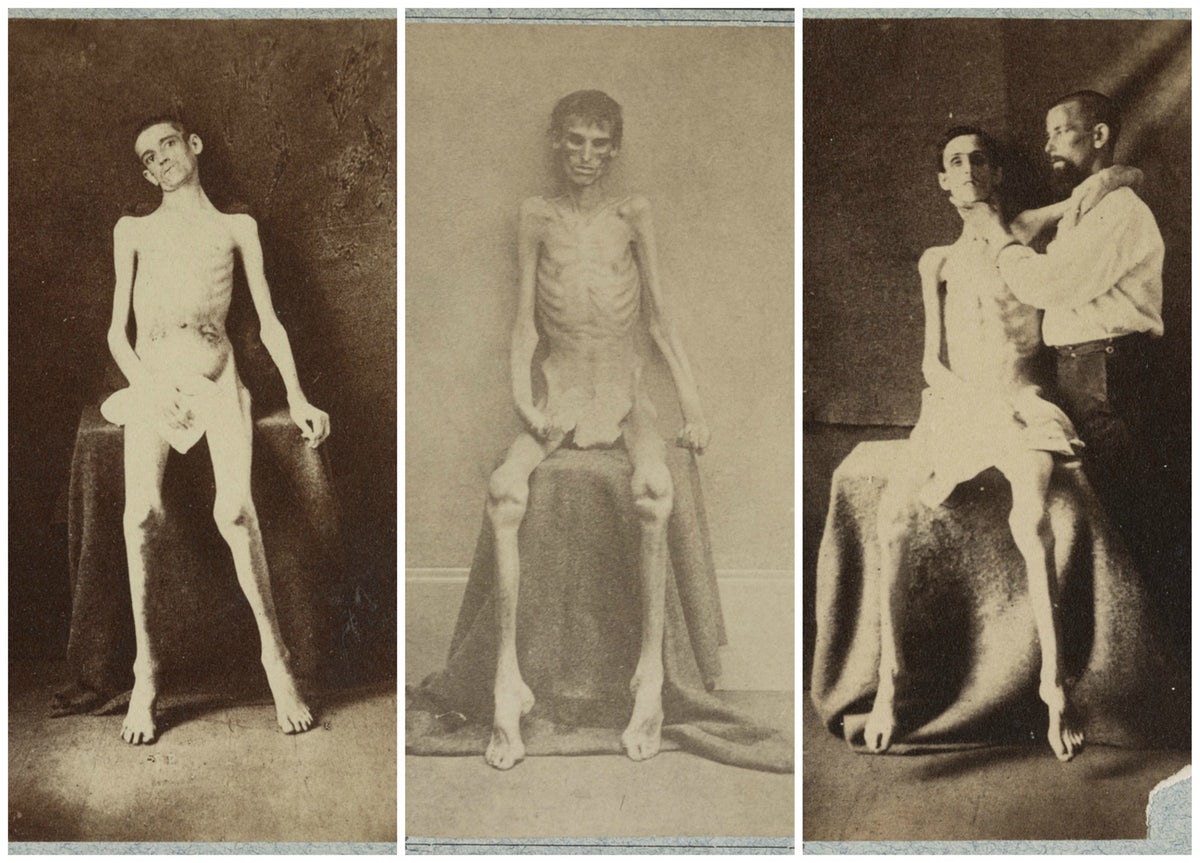

The best account of the nightmarish conditions at Andersonville comes from a Confederate surgeon who visited the prison for three weeks in 1864 and prepared a report on his finding for the CSA's Surgeon General. The surgeon was Dr. Joseph Jones and his mission to Andersonville was not a humanitarian one. Confederate authorities supported his mission to find out what they might learn "for the benefit of the Confederate Army."

Wirz was not anxious to have the prison he ran examined and reported on. He initially refused to admit Dr. Jones to the stockade. Only when he received a direct order to allow Jones in from Captain W. S. Winder, did Wirz relent. Jones spent three weeks beginning in mid-September of 1864 Andersonville. As a surgeon, he was particularly interesting in observing conditions within the prison's hospital, but his report covered all aspects of life at Andersonville. Jones's report would become part of the evidence against Wirz in his 1965 trial, but that was clearly never the doctor's intent. After the trial, in fact, Dr. Jones wrote that he experienced "deep pain" in seeing his report, which "was designed to promote the cause of humanity" be "applied to the prosecution of criminal cases." While Dr. Jones diagnosed the problems at Andersonville as massive and at least partially preventable, he also was quick to note that conditions were as they were in large part because of "the distressed conditions in the southern states."

Yet, in the conclusion of his report, Dr. Jones begged for action to address the "crowding, filth, foul air, and bad diet" he found at Andersonville. He urged changes in hospital procedures, treatment of the dead, water sanitation, and more food. As Jones put it, "This gigantic mass of human misery calls loudly for relief."

Jones's report is well worth reading in its entirety. But the following passages from the report provide an idea of the almost impossibly bad conditions he found during his visit.

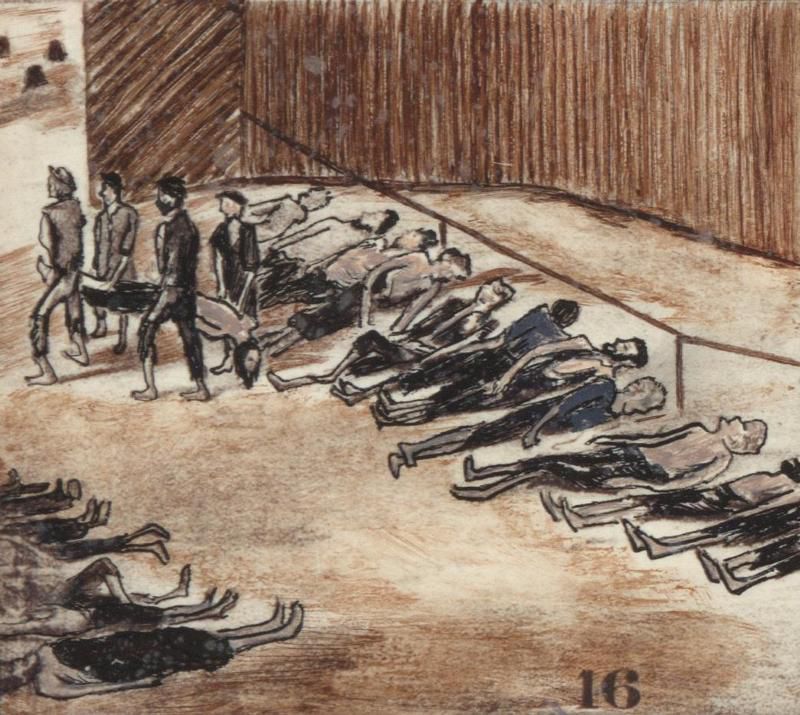

Jones reported that owing to piles of open human waste and dead bodies by the hundreds, the smell of the camp was "most nauseous and disgusting." He wrote that "the manner of disposing of the dead was calculated to depress the already desponding spirits of the men." He described the dead laid out in front of their tents, with the job of disposal of the bodies assigned to African-American Union soldiers. The soldiers eventually carted the bodies to the dead house where "corpses lie upon the bare ground, and were in most cases covered with filth and vermin." When they were finally buried, they were placed so close to ground level as to still allow the death odors to befoul the camp.

Jones reported that "the police and hygiene of the hospital was defective in the extreme." He wrote, "Millions of flies swarmed over everything and covered the faces of the sleeping patients, and crawled down their open mouths, and deposited their maggots in the gangerous wounds of the living, and in the mouths of the dead."

Jones said that "the surface of the low grounds [of the camp] were "covered with excrements." The poor construction of sinks over the lower portion of the stream that ran through the prison caused excrements to largely not be washed away, but rather "accumulated upon the low boggy ground. The volume of the water was not sufficient to wash away the feces" and they "formed a mass of liquid excrement." It got worse. "Heavy rains," Jones wrote, "caused the water of the stream to rise...and feces overflowed the ground and covered them several inches" after the waters subsided. Jones added, "The action of the sun upon this putrefying mass of excrements and fragments of bread and meat and bones excited most rapid fermentation and developed a horrible stench."

Andersonville's hospital

One can certainly argue that the blame for the horrors described by Dr. Jones in his report to Confederate authorities cannot all be placed on Wirz. Things were really bad in the South in 1864. But Wirz seemed to take a certain pride in all the death at Andersonville, boasting on several occasions--according to testimony presented at his trial--that he was "doing more than General Lee" to kill Union soldiers. So much so that prosecutors would later argue that Wirz's real solution to the problem of overcrowding at Andersonville was simply to kill lots of prisoners.

Wirz, in his trial, would be blamed for much of the death and misery in Andersonville, but so would other Confederate authorities, including Wirz's superior officers and others with significant responsibilities for operation of the camp. Many in the prosecution team believed responsibility for Andersonville ultimately rested with CSA President Jefferson Davis. (In fact, the first charges drafted by prosecutors named Davis as a co-conspirator, but the War Department ordered new charges drafted with Davis's name conspiculously omitted from the list of conspirators.) The first charge against Wirz, in the legalese of the time, states, "That he, the said Henry Wirz, did combine, confederate, and conspire....to maliciously, traitorously, and in violation of the laws of war, to impair and injure the health and to destroy the lives--by subjecting to torture and great suffering; by confining in unhealthy and uuwholesome quarters; by exposing to the inclemency of winter and to the dews and burning sun of summer; by compelling the use of impure water; and by furnishing insufficient and unwholesome food--of large numbers of Federal prisoners, to wit, the number of 30,000 soldiers in the military service of the United States of America...to the end that the armies of the United States might be weakened and impaired and the insurgents engaged in armed rebellion against the United States might be aided and comforted.

The charge goes on and on. It says, "And he, the said Henry Wirz, an officer in the military service of the so-called Confederate States, being then and there commandant of a military prison at Andersonville,...fully clothed with authority, and in duty bound to treat, care, and provide for such prisoners...did...maliciously, wickedly, and traitorously confine a large number of such prisoners of war,...in unhealthy and unwholesome quarters, in a close and small area of ground wholly inadequate to their wants and destructive to their health, which he well knew and intended." The charge goes on to talk about Wirz's neglect of prisoners "in the incemency of witnter and the dews and burning sun of summer," before finally blaming him for minds impaired, intellects broken, and the deaths of more than 10,000 men.

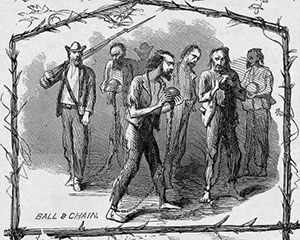

Andersonville prisoners with balls and in chains

Yet, despite the days of testimony and mountains of evidence that prosecutors will amass about the suffering of the thousands at Andersonville, it is the deaths of only a dozen or two Union soldiers that will command the attention of the Commission when it makes its final judgment in the Wirz trial. Specifically, those soldiers alleged to have murdered by Wirz--either by his own hand, by his specific orders to guards, by vicious dogs under his keep, or through the use of inhumane punishments such as the stocks and chain-gangs.

August of 1864 (the month before Dr. Jones made his inspection) was the worst of the worst at Andersonville. Confederate officials, by the end of July, were well aware of the fact that conditions at Andersonville had grown intolerable. CSA Secretary of War James Seldon had, in fact, issued an order that no new prisoners be brought to Camp Sumter. But then the Battle of Atlanta happened. Thousands of newly captured prisoners were sent on their way to Andersonville for lack of a better alternative. Prison populations in August reached as high as 35,000 prisoners, with prisoners dying at a rate of well over 100 per day, mostly from scurvy, gangrene, and dissentery. On one single day in August, over 200 prisoners died, the highest number in the history of Andersonville.

By fall of 1864, prison populations had fallen dramatically. By the end of November, only about 1,500 prisoners remained at Andersonville and escapes were a frequent occurrence. With the end of the war in sight, on March 15, 1865, General Ulysses S. Grant and Confederate Agent of Exchange, Judge Robert Ould, agreed to resume prisoner exchanges. Almost all remaining prisoners at Andersonville were handed over to Federal authorities at an agreed location in Mississippi.

Four weeks later, on April 9, Robert E. Lee surrendered his Army of Northern Virginia and, for all practical purposes, the Civil War was over. Of course, there was the unfortunate matter of an assassination the next week. And, eleven days after John Wilkes Booth shot President Lincoln, Booth was himself shot on a farmstead in Virginia by Boston Corbett, a former prisoner at Andersonville.

By the end of April, only a few prisoners remained at Andersonville, only those too sick to have participated in the prisoner exchange. The last of 12,912 prisoners to die at Andersonville was buried, and the camp was closed.

Survivors of Andersonville

On May 7, 1865, U. S. Captain N. E. Noyes uarrested Henry Wirz at Andersonville under orders of Major General James H. Wilson. Wirz promptly made it clear he thought he was exempt from prosecution under the terms of surrender. The next day, Wirz wrote to U. S. Major General James H. Wilson claiming he had done nothing wrong and asked for safe conduct. He expressed the desire to return to Switzerland with his family and hoped that the general might guarantee his safe conduct.

That was not to be. Camp Sumter commander George C. Gibbs , seeking to avoid prosecution himself, wrote a lettetr to U. S. General E. M. McCook placing the blame for what happened to prisoners at Andersonville squarely on Wirz. Gibbs noted that Wirz, and not he, had direct control over prisoners. By the end of May, Henry Wirz sat alone in a cell in the Old Capitol Prison in Washington D.C. He would sit there for nearly two months until his trial before the Special Military Commission opened.

Awaiting trial, Wirz prepared a list of witnesses who he hoped would help prove that the conditions at Andersonville were beyond his control. He also tried to mount a publicity campaign of sorts. In late August, Wirz sent a letter to the New York News proclaiming his innocence, identifying ways in which he tried to alleviate the horrible conditions, and complaining about the unfairness of the upcoming proceeding against him. His campaign faced an uphill battle. In the months since his arrest, Wirz had been villified in the northern press and calls to "Hang Wirz!" were being heard everywhere.

The Trial

The structure and conduct of the Wirz trial was a project of the War Department. On August 21, 1865, the nine-member Special Military Commission met for the first time in the Court of Claims room in the Capitol Building. The president of the court was Major General Lew Wallace (who would later go on to write the novel Ben Hur). The purpose of the meeting was to development the procedures and rules of evidence that would govern the Wirz trial.

Trials by military commission differ in major respects from criminal trials in civilian courts. Unsurprisingly, they are less fair to defendants. For starters, their jury is not one of "their peers." Rather, as in this case, the jury consists of high military officials who recently completed a war in which the defendant was one of the enemy. Moreover, verdicts typically do not require unanimity as they would in civilian trials. In addition, the rules of evidence in military commission cases are almost always tilted against defendants. In Wirz's case, for example, the "you-did-it-too" defense (the argument that some of these same alleged crimes might have occurred against Confederate prisoners at some northern prisoner of war camps) was specifically excluded. Testimony regarding the ending of the prisoner exchange was excluded as irrelevant. On the other hand, evidence that would be excluded as "hearsay" in a civilian trial was generally admitted.

The fact that the Wirz trial was not as fair as it might have been does not mean that it was a kangaroo court or that the commission lacked integrity. Colonel Norton Chipman, a young lawyer who handled much of the preparation of the government's case, called the members of the commission "unimpeachable."

Wirz spent most of his trial lying on a couch, with his defense attorney at a table nearby. Wirz was suffering from an inflamed wound, among other health problems. The nine members of the commision sat around a large table in the middle of the high-vaulted room.

Wirz on a couch during his trial

The trial opened with Secretary of War Edwin Stanton reading the charges and specifications against Wirz. Wirz entered his plea of not guilty. The government, almost immediately, began having second thoughts about the brad conspiracy in the first charge against Wirz, which charged Wirz with conspiring with Jefferson Davis, General Lee, CSA Secretary of War Seddon and others. The next day, the government came back with a new indictment, one which simply charged Wirz with "conspiring with persons unknown."

The first set of prosecution witnesses testified as to the terrible conditions that existed at Andersonville. Witnesses included both Confederates and Union prisoners. Excerpts from the report of Dr. Jones were read into the record. At the conclusion of the this phase of testimony, no one could doubt the tragedy that was Andersonville--only whether the conditions that existed there could be in any way called a violation of the laws of war committed by Henry Wirz. The Wirz defense team did its best to argue that Andersonville was simply a reflection of the sorry conditions of the South at that time, and nothing for which Wirz should be held criminally responsible.

Legal and moral responsibility had a much clearer focus in the second phase of the trial, which focused in large part on actions allegedly taken by Wirz against specific prisoners that led to their deaths. Deaths that the prosecution argued amounted to war crimes, as spelled out in Charge 2 and its 13 specifications.

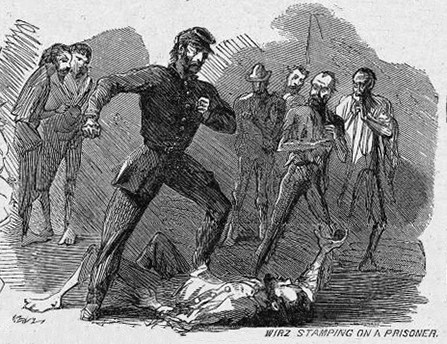

The murders allegedly committed by Wirz fell into four broad categories, as laid out in the indictment. First, there were the murders—viewed as the most serious crimes of all by the Commission—that Wirz was said to have committed by hand, usually with a gun, but in one case by stomping and beating a prisoner to death. Second, there were the instances in which Wirz allegedly directly ordered guards to shoot prisoners. A third category included deaths resulting from the use of inhumane punishments, either stocks or chain-gangs. And lastly there were cases involving hounds under Wirz’s command who, according to the charge in the indictment, killing “about fifty” men, mostly prisoners trying to escape Andersonville.

Although most of the attention in this account will consider the murders Wirz allegedly committed with his own hand, murders in each of the four categories was the subject of testimony by multiple witnesses in the two-month long trial, and each deserves at least brief discussion.

Testimony concerning Wirz’s command of vicious dogs captured considerable attention at the time of the trial. Even the language in the indictment could make hair stand. The charge said: “Wirz, still pursuing his evil purpose, did keep and use ferocious and bloodthirsty beasts, dangerous to human life, called bloodhounds, to hunt down prisoners of war.” The charge said Wirz “incited and encouraged” the beasts to seize, tear, mangle, and maim the bodies and limbs of said fugitive prisoners.”

One former prisoner, in a failed escape attempt, found himself surrounded by hounds and feared the worst. But the man with the hounds “called the dogs off.” The witness said the man said, “The old captain [Wirz] told me to make the dogs tear you, but I know myself what it is like to be a prisoner” and “I would not do that.” When the prisoner was returned to camp, Wirz’s first question for the dog’s keeper was “Why didn’t you make the dogs bit him?” Another witness, James Stone, reported seeing, in August 1864, a prisoner badly mangled by dogs. He described watching Wirz as “he shook the tree” in which an escapee had climbed. When the prisoner fell to the ground, Wirz “allowed the dogs to tear him.” Stone told the Commission, “I understand that he died that night.” Witness John Heath described seeing Wirz and his dogs tree an escaping prisoner. Wirz ordered the man down and then let the dogs at him. According to Heath, “Wirz did not try to keep the dogs off the man” though he “could have done so.” Other witnesses recalled seeing “the calf of [a prisoner’s] leg pretty nearly off” and other grisly dog-inflicted wounds. One witness saw a prisoner who had “part of his cheek torn off” and “his arms and legs so gnawed up” than the man “only lived twenty-four hours after.” Boston Corbett, who later gained famed for shooting John Wilkes Booth, told the Commission an interesting tale about be cornered by Wirz’s dogs, only to be miraculously spared. When asked what kept the dogs from ripping and tearing him like many of the other escaping prisoners, Corbett replied, “the same Power that kept the lions from biting Daniel to pieces.”

Sketch of sole surviving dog, a Cuban bloodhound, from the pack kept at Andersonville

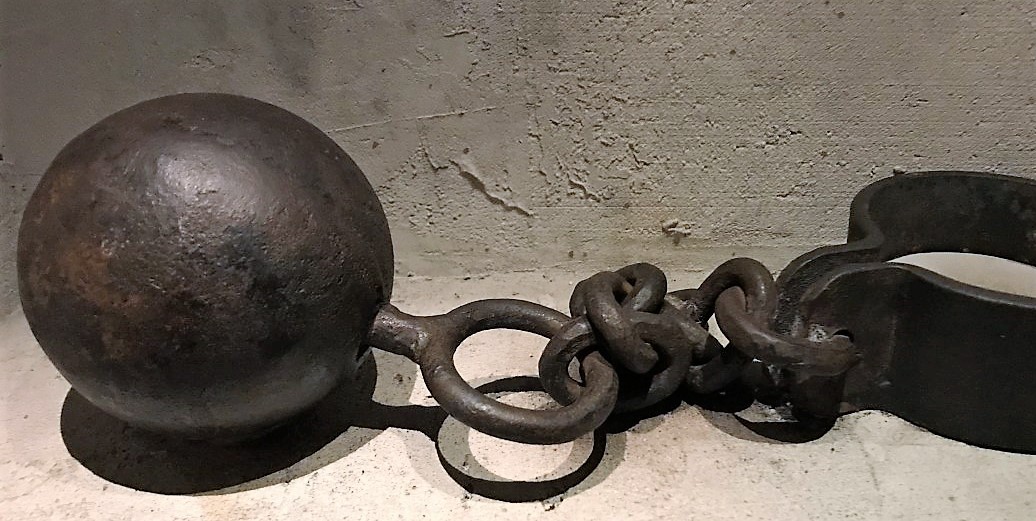

According to the indictment, Wirz’s use of inhumane treatment caused a total of about 430 deaths. (At best, this number should be considered a wild guess.) The stocks were said to have resulted in about thirty deaths. The charge said, “Wirz did cruelly treat and injure said prisoners by maliciously confining them within an instrument of torture called the ‘stocks,’ thus depriving them of the use of their limbs, and forcing them to lie, sit, and stand for many hours without the power of changing position, and being without food or drink.” Wirz’s employment of chain-gangs as punishment for “slight, trivial, and fictitious” offenses was alleged in the indictment to have caused the deaths of an additional 100 prisoners “whose names are unknown.” The chain-gang punishment, as described in the indictment, was accomplished “by fastening large balls of iron to their feet, and binding large numbers of the prisoners closely together with large chains around their necks and feet, so that they walked with the greatest difficulty--and, being so confined, were subjected to the burning rays of the sun, often without food or drink for hours, and even days.” The “dead-line” cost the most lives of prisoners, 300 according to the indictment. The dead-line was described as “a line around the inner face of the stockade or wall inclosing said prison, and about twenty feet distant from and within said stockade, which was in many places an imaginary line, and in many other places marked by insecure and shifting strips of boards nailed upon the top of small and insecure stakes or posts.” According to the charge, “Wirz “maliciously and needlessly” instructed the prison guards stationed around the top of said stockade to fire upon and kill any of the prisoners aforesaid who might touch, fall upon, pass over or under or across the ‘dead-line.’”

Several witness described two types of stocks, the “foot stocks” and the more dreaded “spread eagle” stocks in which prisoners were forced to stand with their arms extended. Witness James P. Stone testified that Wirz ordered prisoners put into stocks “because they failed to appear at roll call in the morning or to answer their names when called.” Even “asking Captain Wirz for something to eat” could put you in the stocks, Stone said.

Ball and chain from Andersonville

The chain gangs were described in the testimony of many prosecution witnesses. Among them was Dr. A. V. Barrows described seeing as many as 18 men at a time “chained together in a circle.” He said he had “no doubt” men died from being together for up to “two weeks” at a time, though he did personally see anyone in a chain gang expire. Barrows testified he saw a prisoner who died during a stint in the chain-gang and who still had a “band around his neck fastened with bolts.” James Stone testified that he knew of men being chained together “for six or eight weeks” and saw one dead with a 32-pound ball still attached to his leg.

A shooting at the dead-line

Dozens of witnesses testified about shootings at the dead-line. Boston Corbett testified that he saw “several” prisoners “carried way” after being killed for crossing the dead-line. He said “the horror and misery” of Andersonville was so great “that I myself had thoughts of going over that dead-line to be shot in preference to living there.” Corbett testified that many “new prisoners were shot without having been warned about the deadline” or “knowing where the deadline was.” Jacob Brown described watching Wirz order a sentinel to shoot men that had crossed the dead-line to “get water from a brook.” Brown testified said “I saw where the ball entered the breast” of one of the prisoners. Other witness reported similar shootings under Wirz’s order. Witness O. S. Belcher testified that he saw “a cripple” on a crutch approach the dead-line and beg a guard to shoot him. The guard refused, but Wirz ordered him to fire. The prisoner, known as “Chickamauga,” was hit it jaw by a ball and killed. Belcher said that “I have seen 25 or 30” men killed for crossing the dead-line. Thomas Hall recounted a night in August when a prisoner “reached his hand over the dead-line to get some pine burs to cook his victuals with.” The guard fired at him, but missed the prisoner and instead hit another prisoner asleep in his tent, blowing part of his skull off.

The prosecution, the defense, and the Commission all understood the most damning specifications in the indictment to be those that alleged Wirz to have committed murders with his own hand—usually with a gun, but in one case by stomping and beating a prisoner to death. Interested readers should examine the linked document entitled “Wirz Shooting Prisoners: The Testimony” for a fairly comprehensive review of what prosecution witnesses had to say on this subject in the trial. Here, we will focus on the testimony of George W. Gray, the prosecution witness who provided the most detailed and vivid description of an instance in which Wirz shot and killed a prisoner.

Gray’s testimony came near the end of the trial, on September 22. Gray spoke in a strong, confident voice. Cross-examination by Wirz’s attorney, Louis Shade, did little to shake his testimony. According to reports, Wirz rose from his couch to challenge Gray’s story, but Gray’s clear and consistent account of his murder of a Union soldier and prisoner named William Stewart, caused Wirz to sink “back hopelessly” in his couch—which the press took to be a sign of his remorse and his guilt.

The shooting described by Gray took place about noon on a mid-September day in 1864. Wirz testified that he and Stewart, a member of the 9th Minnesota infantry, had left the stockade ostensibly to lay the body of a dead prisoner in the dead-house. They had deposited the body and were with a guard about 50 yards from the dead house when Wirz rode up a horse and demanded to know “by what authority we were out there.” Stewart replied that “we were there by proper authority. Wirz said no more, but drew a revolver and shot the man” in “the breast,” instantly killing him. Wirz “told the guard to see what he has.” The guard took “about thirty dollars” from Stewart’s body, which Wirz pocketed. Then he “rode off, telling the guard to take me to prison.”

In testimony that probably adds to, rather than subtracts from, the credibility of Gray’s story is his admission that “Stewart begged for the dead body” and they carried it to the dead-house as part a planned escape and that, in fact, Stewart lied when he told Wirz they had “proper authority” to be where they were. Gray also admitted, “I was trying to bribe that fellow [the guard]—I was trying to get away.”

Judge Advocate General Joseph Holt asked Wirz to stand. Is “that the man who shot your comrade?” Holt asked. “That is the man,” Gray replied.

In Shade’s summation, he argued that Gray’s testimony was a fabrication. But Holt, in his report to President Johnson at the trial’s conclusion, stated “nothing in the examination of the record casts doubt on Gray’s testimony” and there was “nothing in his manner on the stand to raise the question of his credibility.” Although there were several other witnesses who described several other prisoner shootings by Wirz, Gray’s testimony—standing alone—would have been enough to convict Wirz and earn him a death sentence.

The day after Gray’s testimony, Leslie’s Illustrated said, “The evidence…is so clear and abundant that the vilest Copperhead and the most outrageous rebel can offer no excuse or apology for him.”

After 67 days, and after a parade of 167 prosecution and defense witnesses to the stand, the trial of Henry Wirz ended. The Commission found Wirz guilty on charge 1 (conspiracy) and on 10 of the 13 specifications of murder in charge 2. In a decision signed by the Commission’s President, General Lew Wallace, the Commission declared, “And the Court do sentence him, the said Henry Wirz, to be hanged by the neck until dead.”

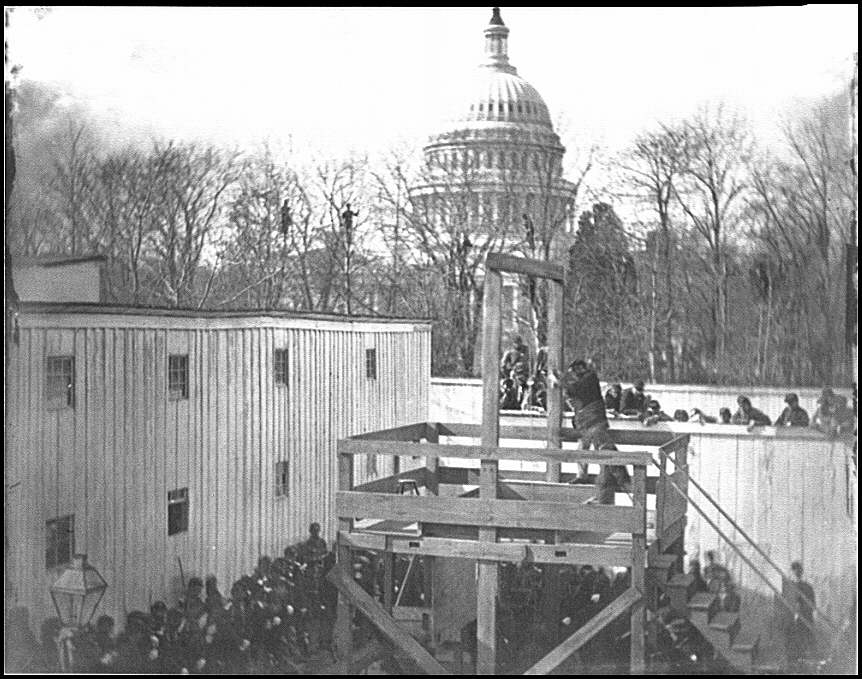

The hanging of Henry Wirz, November 10, 1865

Judge Advocate General Joseph Holt send a report on the Wirz trial to the president on October 31. Holt wrote, "Criminal history presents no parallel to this monstrous conspiracy" and that "a system for the murder of men more revolting in its details could not have been planned." Holt told the president, "All the horrors of this pandemonium of the rebellion are laid bare to us in the broad steadyy light of tthe testimony" of the "witnesses who spoke what they had seen and heard and suffered." Holt insisted that the trial was "conducted throughout with patience and impartiality." He pointed out that Wirs was allowed to introduce evidence of "acts of kindness to prisoners" and to introduce his own explanations for his actions. Moreover, "every witness asked for by the defense was subpoenaed except certain rebel functuaries." The report detailed the evidence supporting the Commission's conviction and ended with the recommendation "that the sentence be executed."

On November 3, 1865, President Johnson approved the findings and sentence of Commission and ordered that Wirz be hanged on Friday, November 10.

Before learning the date of his execution, Wirz penned a letter to the president: “The pangs of death are short, and therefore I humbly pray that you will pass on your sentence without delay. Give me death or liberty. The one I do not fear; the other I crave.”

Wirz was led from his cell to the courtyard of the Old Capitol Prison on the appointed day. He left behind a white kitten that had been his companion for his last few months. He accepted his fate with courage. Leslie’s Illustrated said of his execution that there was “something in his face and step which, in a better man, might have passed for heroism.”