Thomas Wolfe called Confidential (1952-58) "the most scandalous scandal magazine in the history of the world." Today, that statement may no longer be true, but in the relatively tame decade of the 1950s, Confidential went where no publication had gone before in exposing to a curious public the private lives of celebrities. In so doing, the magazine earned the wrath of powerful Hollywood figures who convinced California's attorney general to file an array of criminal charges that the movie moguls and stars hoped would silence Confidential and its flamboyant publisher, Robert Harrison . The trial that followed sent the celebrities whose exploits were described in Confidential off in different directions: some to testify in a Los Angeles courtroom and some across the California border or out to sea to avoid defense subpoenas. Truth, after all, is a defense in a libel case. When it was over, Confidential was a different magazine and Hollywood was a different place.

The Rise of a Scandal Magazine

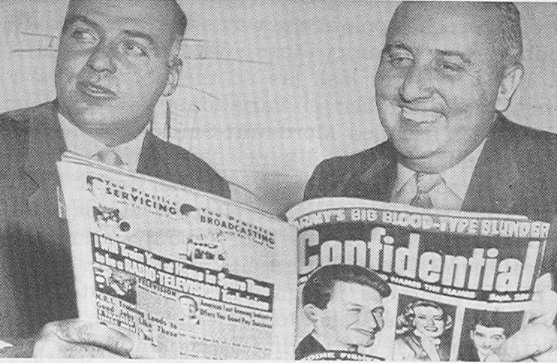

When his accountant told Robert Harrison that the six girlie magazines he published were all losing money and headed for bankruptcy, he began thinking about a new type of magazine. "That same week," Harrison said later, "I thought up Confidential." Six months later, in December 1952, the first issue hit the newsstands. By Harrison's own admission, the first issue was "terrible."

With the next issue, however, Confidential's fortunes began to turn. Among the stories featured was one titled, "Winchell Was Right About Josephine Baker." The article suggested that popular broadcaster and columnist Walter Winchell had been wrongly attacked as a racist for his criticism of African-American entertainer and actress Josephine Baker. The controversy revolved around an October 1951 incident at New York City's famed Stork Club, owned by a bigoted Oklahoman named Sherman Billingsley. As it happened, both Winchell and Baker, at separate tables, were at the club that night. When a waiter served Baker's white companions but did not deliver the steak and crab salad she ordered, the fuming entertainer walked out--and, within days, the NAACP, New York papers, and Ed Sullivan were all on the Stork Club's case, denouncing the presumed discrimination against Baker. Baker's complaints did not end with the Stork Club, but included Winchell, whose nonchalance about the incident came under her biting criticism. Winchell, however, felt falsely accused, defended the club, and lashed out at "phoney" Baker, who he also suggested was a Communist. The Confidential story sided with Winchell and chastised Baker for being an "outright liar" who fights racial discrimination "for her own cynical ends." Winchell, unsurprisingly, loved the story and encouraged his readers and viewers to read the full story in Confidential. With the Winchell testimonial, sales skyrocketed. Harrison would later say, "That was what really made Confidential, the publicity." From then on, Robert Harrison would try to include in every issue of his magazine at least one article that he thought might win the hearty approval (usually by taking on one of the broadcaster's enemies) of Winchell and garner another on-the-air promotion for his magazine. In Harrison's words, "It got to the point where some days we would sit down and rack our brains trying to think of somebody else Winchell didn't like. We were running out of people, for Christ's sake!"

Howard Rushmore

The Winchell connection also led to the hiring of Confidential's first writer of a national stature, Howard Rushmore, a leading anti-Communist columnist for William Randolph Hearst's New York Journal-American. Although Confidential's meat-and-potatoes was celebrity gossip, Rushmore's political pieces would, in Harrison's opinion, give some weight and respectability to his publication. While Harrison devoted his attention to making trouble for suspected leftists, such as in a story detailing an affair between physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer and a medical student with "Red friends," other writers mined sources for juicy tidbits about the private lives of movie stars, singers, and ball players.

The subjects of Confidential's stories constitute a virtual "Who's Who?" of 1950s celebrities. Among those whose behavior, usually boorish or sexy (and often at parties or in bedrooms), captured the attention of the magazine's writers were Clark Gable, Grace Kelly, Humphrey Bogart, Tab Hunter, June Allyson, Mickey Mantle, Rita Hayworth, Groucho Marx, Kim Novak, Bob Hope, Tommy Dorsey, Orson Welles, Liberace, Joan Crawford, Maureen O'Hara, Otto Preminger, Marlene Dietrich, Dorothy Dandridge, Joe DiMaggio, Frank Sinatra, Tallulah Bankhead, Sammy Davis Jr., Ava Gardner, Burt Lancaster, Tony Curtis, Peter Lorre, Jayne Mansfield, Robert Mitchum, Eddie Fisher, and Marilyn Monroe. However uncomfortable stars found the attention, as Samuel Bernstein, in his biography of publisher Robert Harrison, concludes about what some called "The Movieland Massacre": "No one's career was destroyed, no one's life wrecked, and no one died."

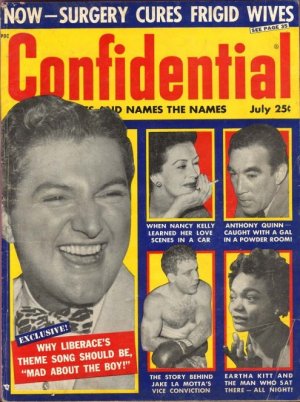

Several Confidential stories broke new ground in exposing or suggesting celebrity homosexual conduct. "The Untold Story of Van Johnson" revealed that the screen idol was "an admitted homosexual," but had undertaken a "desperate"--and successful--"effort to rid himself of his abnormality." In "The Untold Story of Marlene Dietrich," Confidential revealed that the actress has "not only played both sides of the street, but done it on more than one occasion"--including with "a blonde Amazon" from Germany. Tab Hunter, the magazine reported, was once arrested at a gay pajama party. In "Why Liberace's Theme Song Should Be, 'Mad About Boy,'" described an evening at at Dallas hotel when the musician succeed in pinning a handsome press agent, Dimples: "A referee certainly would have penalized the panting pianist for illegal holds."

Other recurrent themes in the magazine's pages were indecent exposure and public lovemaking. In "Robert Mitchum...the Nude Who Came to Dinner!," Confidential described a private party in which the actor "slowly but solemnly removed every bit of his clothing--down to his socks." Then, as the "other celebrants watched in hypnotized silence" Mitchum "liberally sprinkled" his private parts with ketchup before announcing, "This is a masquerade party, isn't it?--Well, I'm a hamburger." Digging into history, the magazine reported in "They Started in Their Birthday Suits!" that in 1930 in Austria, Hedy Lamarr, then a "young nymph, scarcely over 15 but with a beautifully matured body, slid sinuously into a brook...unencumbered by anything so prosaic as a bathing suit." In a story that would play a significant role in the 1957 trial, Confidential described an incident at Grauman's Chinese Theatre involving actress Maureen O'Hara and her "south-of-the-border sweetie." The story reported that an usher "got the shock of his life" when he discovered O'Hara and her boyfriend "heating up the back of the theater as though it were mid-January." In another story that would become a trial focus, Confidential claimed that African-American actress Dorothy Dandridge enjoyed outdoor lovemaking with a white boyfriend in the woods near Lake Tahoe. (In the 1950s, with many state miscegenation laws still on the books, Confidential frequently reported on the bi-racial lovemaking of stars such as Sammy Davis Jr. and Ava Gardner.)

The magazine's formula was remarkably successful, with circulation passing the 5 million mark by 1956. Robert Harrison thought the success largely due to Confidential's liberating effect: "Women's lives are on the more inhibited side. So they live in the minds to a great extent. When they read about other women who are doing the things that they think about, perhaps what they might want to do,...this is great excitement to them." Writing in Commonweal, commentator John Sisk had a different explanation. He believed that the magazine's phenomenal record was the result of the satisfaction a public, "envious of successful and prominent people," felt in having stars brought down to earth.

Legal Troubles Mount

The first effort to block circulation of Confidential came on August 27, 1955, when the Solicitor of the Post Office issued a "Withhold From Dispatch" order against the magazine. Although most of Confidential's sales came from newsstands, not subscribers, Harrison took the Post Office to court and won a federal court order requiring the government to provide a prompt hearing if found anything in a particular issue that it found violated federal obscenity laws. In 1956, the Post Office and Confidential battled over issue after issue, but the magazine prevailed in each instance, with the liberalizing trend in federal obscenity law working in the magazine's favor. Finally, by the end of 1956, the Post Office dropped its requirement that Confidential supply the agency with issues in advance of publication, though without dropping the threat of a fight should the Post Office conclude that the magazine overstepped the obscenity line.

California attorney Jerry Giesler, speaking for many Hollywood insiders, declared war on Confidential: "My clients have decided to fight...We'll hound them through every court in the country. We'll file civil libel suits and criminal libel complaints...The smut is going to stop." The libel suits began. Lisabeth Scott sought $2.5 million in her suit, Robert Mitchum asked for $1 million, and Doris Duke filed suit for $3 million.

Meanwhile, others in the California movie industry sought the intervention of State Attorney General Edmund "Pat" Brown. In early 1957, Brown's office launched an investigation of Confidential. A grand jury empaneled in spring heard from celebrity witnesses including Maureen O'Hara, June Allyson, Mae West, Walter Pidgeon, and Liberace. Former Confidential writer Howard Rushmore, having resigned from the magazine with complaints about the publisher's plans to hire liberal writers to help balance his decidedly conservative slant, also testified before the grand jury. On May 15, 1957, the grand jury returned indictments on charges of conspiracy to publish criminal libel, conspiracy to publish obscene material, and conspiracy to disseminate information in violation of California's business code (articles about abortion and "male rejuvenation.") Eleven individuals and three companies, including Confidential and Hollywood Research (the magazine's California research arm) were indicted. The A.G.'s Office promised prison terms for violators. Assistant Attorney General Clarence Linn confidently predicted to the press: "The jail doors are clanging for these people."

There was one major initial obstacle for the prosecution. All but two of the indicted individuals, including publisher Robert Harrison, had residence outside of California and two of the three indicted corporations (excluding only Hollywood Research) were based in New York. The two Californians indicted, Marjorie and Fred Meade of Hollywood Research, were nephews of Harrison. All others would have to be extradited--and New York was not especially sympathetic to California's demand. In the end, each of the New York residents indicted escaped extradition, as the New York courts concluded libel was not an extraditable offense under state law. After some internal debate, unhappy prosecutors decided to press ahead with a trial for the Meades and Hollywood Research.

The Trial

Robert Harrison decided on an aggressive defense. He hired one of California's most prominent defense attorneys, Arthur Crowley. Also on the defense team would be Confidential's house counsel, Albert DeStefano. Crowley sent shock waves through Hollywood when he publicly announced plans to subpoena 200 stars to testify. Truth after all, Crowley noted, was a defense to libel. The lawyer stated his intentions to ask witnesses about any and all aspects of their private lives that might be relevant to the charges.

Crowley's announcement caused panicked studio bosses to approach Attorney General Brown about dropping charges, but Brown expressed his determination to see the trial through. Stars fearing subpoenas began fleeing for the hills--or, at least, places outside the borders of the state of California. Art Crowley compared the mass departures to the Exodus from Egypt. Some stars, such as Lana Turner, were caught with subpoenas on their way out of town--Turner at the Los Angeles Airport. Others tried valiantly, but unsuccessfully, to escape service, such as Dan Daily who, during his performance at the Hollywood Bowl, leaped from the stage into the audience after he spotted a process service lurking in the wings. Others had better luck: Frank Sinatra sailed his yacht into international waters, while Clark Gable enjoyed a long vacation on a Spanish beach.

Robert Harrison editorialized on the upcoming trial in a two-page publisher's note in Confidential. Harrison stated the magazine was "prepared to prove the truth." He ended his note by expressing confidence that no American jury could be persuaded that truth can be libelous:

We do not underestimate this effort to "get" us. We concede that those who want to "finish" us are powerful and resourceful. They have some tricky arguments; they are artists in the old three-shell game. But we expect to survive. For we believe that even those Americans who may not like what we say will, nevertheless, defend our right to say it. We doubt that the time has arrived when Americans can be "gotten" for the crime of telling the truth.

Judge Herbert V. Walker seemed, to prosecutors, all too willing to force celebrities to the witness stand. Walker warned those who hinted that they might ignore subpoenas to testify: "They'll come to court even if I have to send officers with handcuffs to get them!" The judge's tough talk precipitated settlement discussions. Harrison agreed to pay a modest fine and change the focus of his magazine away from Hollywood gossip in return for the dropping of all charges. Much to the surprise of both prosecutors and defendants, however, Judge Walker (perhaps looking forward to the limelight) adamantly refused to accept the settlement.

On August 7, 1957, Assistant Attorney General Clarence Linn gave his opening statement to a jury of five women and seven men in Los Angeles's Hall of Justice. Linn described Harrison as the "Mr. Big" of an operation that used prostitutes to lure celebrities into compromising positions, recklessly published falsehoods, and had no qualms about publishing obscene stories. Art Crowley, for the defense, responded by telling jurors that what Confidential reported was published without malice and was true in all important particulars. He said that the Post Office had already determined that Confidential's stories did not constitute obscenity and that the case against the defendants, if it were to be tried anywhere, should be tried in a New York court.

Deputy District Attorney William Ritzi and Linn, playing tag team when vocal cords became strained, entertained jurors with their reading into the record six stories from Confidential which the state argued were either obscene or libelous. With what Samuel Bernstein described as "flawless diction and heated indignation" Ritzi began with his rendition of "It Was a Hot Show in Town When Maureen O'Hara Cuddled in Row 35," then continued with "Only the Birds and the Bees Saw What Dorothy Dandridge Did in the Woods." "Robert Mitchum...The Nude Who Came to Dinner!" was next up, followed by stories about Gary Cooper, Mae West, and June Allyson.

The prosecution's loosely thrown together case continued with Howard Rushmore appearing as the first witness for the state. Rushmore testified that Harrison urged staff to resort to practically any means necessary to dig up juicy stories about Hollywood celebrities, including paying prostitutes and known homosexuals to put stars in compromising positions. Described by courtroom reporter Theo Wilson as "a vitriolic man who obviously loathed what he had become," Rushmore's bitter testimony failed to sit well with several jurors. Samuel Bernstein wrote that Rushmore's testimony basted "the prosecution's case with bile."

Prostitute Ronnie Quillan (called by the press "the Soiled Dove") testified that Confidential paid her $1500 to tell her story about meeting Desi Arnaz (of "I Love Lucy") in a Palm Springs cocktail lounge and then sharing time together in Desi's hotel room. The relevance of Quillan's testimony escaped almost all courtroom observers, since Quillan failed to identify anything in Confidential's 1954 story about Arnaz that might be untrue, and therefor libelous. Apparently, the prosecution believed that the mere fact that Confidential bought stories from a prostitute would make the jury more likely to convict.

The trial took a surprising turn when producer Paul Gregory (host of Robert Mitchum's ketchup party) testified that Marjorie Meade offered to keep a story out of Confidential if he paid her $800. Meade responded to Gregory's charge of blackmail by fainting--and guaranteeing the incident headlines across the country. On cross-examination, Crowley forced Gregory to admit that he was gay, and therefore might have reasons to fear being outed (a term not in use in the 1950s) by the magazine. He raised questions about why Meade, well-off by any measure, would risk jail time for a mere $800. More importantly, Crowley produced credit card records from Meade that proved she wasn't where Gregory claimed she was on the night of the alleged blackmail. For good measure, he proved that the restaurant where they allegedly met was even in business on that date. (Judge Walker's decision to allow Gregory's testimony about blackmail in a trial about libel and obscenity was, quite probably, reversible error.)

As the trial continued, and with dozens and dozens of celebrities facing possible calls to the witness stand, Judge Walker announced that the only future testimony he would allow from stars would have to concern the six specific stories previously read into the record. Samuel Bernstein, in Mr. Confidential , reports that Walker's decision limiting testimony caused "celebrations all over town, with impromptu parties breaking out at the drop of a hat."

When testimony moved to the question of whether actress Maureen O'Hara really lit up temperatures in Row 35, juror LaGuerre Drouet asked Judge Walker whether a jury tour of Grauman's Chinese Theatre , scene of the alleged activity, could be arranged. Judge Walker agreed to the tour idea. The judge, bailiffs, lawyers, and jurors boarded a bus and headed for Hollywood. Reporter Theo Wilson, who was present at the theater, wrote that the highlight of the tour was watching a bailiff try to pry overweight juror Drouet from a seat in Row 35, where he had become lodged while "squirming around in the air, as if cuddling a movie queen." On the witness stand, O'Hara admitted to having a Mexican boyfriend in 1954, but asked whether she had gone with him to Grauman's replied, "Never!" Several defense witnesses contradicted O'Hara, including one who testified that O'Hara all but had sexual intercourse in her lover's lap. A clerk who worked Grauman's candy counter contradicted O'Hara's testimony that she had been to the theater only twice, both times with her brother. The clerk testified that after a visit to the theater by O'Hara one night, she remembered the ushers all abuzz about what had happened in Row 35.

Dorothy Dandridge was the other major star to testify at the Confidential trial. Dandridge testified that policies against racial mixing in Lake Tahoe would have made it impossible that she could have been, as the magazine story about her alleged, walking arm-in-arm with a white band leader at a hotel. "Lake Tahoe at that time was very prejudiced," Dandridge said. "Negroes were not permitted that freedom." She testified that she didn't have "much choice" but to "stay in my hotel suite most of the time." Dandridge firmly denied the story's main thrust, that she had a tryst in the woods: "I never took a walk in the woods with Mr. Terry."

The defense presented witnesses to demonstrate its care in reporting the truth. Two New York lawyers, including DeStefano, testified that they scrutinized every Confidential story for potential legal problems in advance of publication and that Robert Harrison had "never" overruled their legal advice. Michael Mordaunt-Smith, a reporter for the magazine, claimed to have checked out numerous stories for Harrison and never proved one to be untrue. Private investigator Fred Otash told jurors that, far from stretching the truth, Confidential actually often withheld titillating facts about a star to give the magazine leverage in the event of a libel suit.

When defendant Fred Meade finally took the stand on August 26, 1957, he testified (somewhat unconvincingly) that Hollywood Research was independent from Confidential and that therefore much of the content of the magazine's stories could not be attributable to the corporation, himself, or his wife. He angrily denied that either he or his wife ever participated in a blackmail scheme.

After six weeks of testimony, the Confidential case went to the jury--and would be with the jury, as it turned out, for a long time. The jury deliberated longer than any California jury had, until that time, ever deliberated in a criminal case, but still was unable to reach a verdict. When the jury finally threw in the towel on October 1, 1957, the vote stood seven to five for conviction on at least some of the counts. In New York, Robert Harrison celebrated the mistrial. With a violinist on board playing "Mr. Wonderful," he picked up Art Crowley at the airport in his convertible, then threw his lawyer a party and offered him a new Lincoln.

Epilogue

Prosecutors told the press they would retry the case, but they knew that settlement was their only real option. Harrison expected to win again in a second trial, but was anxious to spare family members the agony. In the end, the settlement was almost exactly what was agreed to before the trial started. Harrison promised to pay a token fine (for violating the California Business Code with the publication of articles about abortion pills and male rejuvenation) and shift the focus of his magazine away from Hollywood. Prosecutors agreed to drop all other charges.

On January 2, 1958, Howard Rushmore, broke and bitter and jobless, pulled a gun from his pocket during a ride in a New York City taxi. He put one bullet through his wife, killing her, then put a second bullet in his own head.

Harrison settled outstanding libel suits for trifling amounts, then published a statement in Confidential announcing that the magazine was setting off on a new course. "We're quitting the area of private affairs for the arena of public affairs," he told readers. "Where we pried and peeked, now we'll probe.....It's a big world, a foolish world, a crazy world...and we'll be taking you on an inside tour." The magazine's circulation plummeted. In May, Harrison sold Confidential and moved on to his next thing.

The Confidential trial, for all the threat it posed to free speech, never seemed very much to be about the limits of the first amendment or the precise boundaries of libel or obscenity. It was a trial long on emotion. It was about pride, fear, revenge, and human nature--but none of those things would be changed by any trial outcome. Nor could be changed the basic human desire to peek into the lives of the rich and famous--and so, inevitably, new magazines would eventually rise up to claim the mantle of America's most scandalous scandal magazine.