Directed by Gus Van Sant

Written by Dustin Lance Black

(Won the Oscar for Best Original Screenplay)

128 Minutes (R)

Images

|

|

|

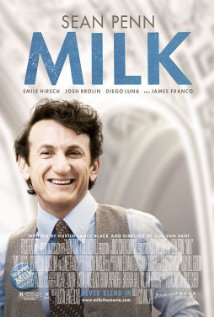

Cast

| Sean Penn | Harvey Milk |

| Josh Brolin | Dan White |

| Emile Hirsch | Cleve Jones |

| Victor Garber | Mayor Moscone |

| Alison Pill | Anne Kronenberg |

| Joseph Cross | Dick Pabich |

| Ashlee Temple | Dianne Feinstein |

| Wendy Tremont King | Carol Ruth Silver |

| Kevin Han Yee | Gordon Lau |

| Diego Luna | Jack Lira |

| James Franco | Scott Smith |

| Denis O'Hare | John Briggs |

| Stephen Spinella | Rick Stokes |

| Lucas Grabeel | Danny Nicoletta |

| Brandon Boyce | Jim Rivaldo |

| Howard Rosenman | David Goodstein |

| Kelvin Yu | Michael Wong |

| Jeff Koons | Art Agnos |

| Ted Jan Roberts | Dennis Peron |

| Carol Ruth Silver | Thelma |

| Tom Ammiano | Himself |

| Boyd Holbrook | Denton Smith |

Reviews

Roger Ebert:

Gus Van Sant's film begins with Harvey Milk at 48, reflecting into his tape recorder about a personal journey that began at 40. At that watershed age, he grew unsatisfied with his life and decided he wanted to really do something. A researcher at Bache & Co. and a Goldwater Republican, Milk became involved with a hippie theater company in Greenwich Village and began to edge the closet door ajar and wave out tentatively.

Milk didn't enter politics as much as he was pushed in by the evidence of his own eyes. He ran for the Board of Supervisors three times before being elected in 1977. He campaigned for a gay rights ordinance. He organized. He acquired a personal bullhorn and stood on a box labeled "SOAP."

His most fateful relationship was with Dan White, a seemingly straight member of the Board of Supervisors, a Catholic who said homosexuality was a sin and campaigned with his wife, kids and the American flag.

"Milk" tells Harvey Milk's story as one of a transformed life, a victory for individual freedom over state persecution, and a political and social cause. There is a remarkable shot near the end, showing a candlelight march reaching as far as the eyes can see. This is actual footage. It is emotionally devastating. And it comes as the result of one man's decisions in life.

Mick LaSalle, San Francisco Chronicle

With "Milk," a great San Francisco story becomes a great American story.

Director Gus Van Sant uses the account of one of the country's first openly gay public officials, who was assassinated in 1978, to invest the gay rights movement with mythic grandeur, as a successor to all the heroic social protest movements in American history. Van Sant's point of view may be a matter of politics, outside the scope of a review, but his success in putting over his point of view is a question of art.

Penn gives us a man who was once closeted and now, as if in response, lives his life completely in the open. He's spontaneous as Penn has never been spontaneous. He's emotional, vulnerable and generous with his laughter. Penn plays him as an utterly liberated man . . .

Van Sant mixes archival footage with new footage - at times, it's impossible to tell one from the other - and it's fascinating to see San Francisco in the '70s. There's color and beauty, but also coarseness; excitement and hope, but with a feeling that something - or everything - just might spin out of control.

One truth "Milk" doesn't need to amplify or manipulate: It's that Harvey Milk's story is part of the San Francisco story, and that story still means something. . .

A. O. Scott, The New York Times

One of the first scenes in "Milk" is of a pick-up in a New York subway station. It’s 1970, and an insurance executive in a suit and tie catches sight of a beautiful, scruffy younger man — the phrase “angel-headed hipster” comes to mind — and banters with him on the stairs.

That would be Harvey Milk (played by Sean Penn), a neighborhood activist elected to the San Francisco Board of Supervisors in 1977 and murdered, along with the city’s mayor, George Moscone (Victor Garber), by a former supervisor named Dan White (Josh Brolin) the next year. Notwithstanding the modesty of his office and the tragic foreshortening of his tenure, Milk, among the first openly gay elected officials in the country, had a profound impact on national politics, and his rich afterlife in American culture has affirmed his status as pioneer and martyr.

For more than two lively, eventful hours, “Milk” conforms to many of the conventions of biographical filmmaking, if not always to the precise details of the hero’s biography. Milk’s inexhaustible political commitment takes its toll on his relationships, first with Scott and then with Jack Lira, an impulsive, unstable young man played by Diego Luna with an operatic verve that stops just short of camp.

Dan White, Milk’s erstwhile colleague and eventual assassin, haunts the edges of the movie, representing both the banality and the enigma of evil. Mr. Brolin makes him seem at once pitiable and scary without making him look like a monster or a clown. Motives for White’s crime are suggested in the film, but too neat an accounting of them would distort the awful truth of the story and undermine the power of the movie.

That power lies in its uncanny balancing of nuance and scale, its ability to be about nearly everything — love, death, politics, sex, modernity — without losing sight of the intimate particulars of its story. Harvey Milk was an intriguing, inspiring figure. “Milk” is a marvel.