The Dred Scott Trials: An Account

by Douglas O. Linder (2019)

Dred and Harriet Scott

Chief Justice Robert Taney’s opinion for the Supreme Court’s 1856 decision in Dred Scott v Sandford is often called the worst in its long history. Charles Evans Hughes, before he became Chief Justice, called the Dred Scott decision our “great self-inflicted wound.”

Both of the two key holdings in Dred Scott v Sandford damaged the long-term reputation of the Court. First, Taney concluded that Dred Scott, an African-American born in the United States, was not a citizen and therefore could not sue in federal courts. Second, the Court held Congress lacked the power under the Constitution to ban slavery in the western territories, thus making any compromise between northern and southern interests on the slave question impossible. The Dred Scott decision therefore set the country on a virtually inevitable course for war. It was arguably the most consequential decision the Supreme Court ever made.

So how did this case make its way to the Court? Like many landmark decisions, it had its origins in the simple desire of one individual, who felt himself a victim of injustice, to seek a court’s help in vindicating his rights.

Background

Dred Scott was born a slave in Southhampton County, in Virginia, around 1800. Dred’s master, Peter Blow, had a large plantation in southwestern Virginia, and later a farm in Alabama. In 1930, at the age of 53, Peter decided to give up farming and take a new course. Peter and his wife, three daughters, and four sons, moved to St. Louis, taking Dred and his other slaves with them.

In the flourishing river city of St. Louis, Blow ran a boarding house called the Jefferson Hotel. But things didn’t work out as Peter hoped. His wife died and his boarding business turned out to be unsuccessful. Peter abandoned the venture and moved his family into another house in 1832. His own health then quickly deteriorated. Peter Blow died in June, 1832.

By 1833, Dred Scott had a new master, Dr. John Emerson, an assistant surgeon in the U. S. Army then stationed at Jefferson Barracks near St. Louis. But Peter Blow’s children, especially Taylor Blow who was age 12 at the time he was orphaned, continued to have a protective interest in their old slave. Most likely, Taylor Blow considered Dred a friend as much as a slave. Taylor Blow would become Dred’s most important supporter in Dred’s long fight for freedom.

In December 1833, Dr. Emerson was ordered to report for duty at Fort Armstrong, 200 miles north of St. Louis in the free state of Illinois. He took Dred, who worked as Emerson’s personal servant at the post, with him. Scott administered vaccines and was hired out to other doctors to help care for the sick.

Fort Armstrong was lacking in amenities, and only two months after his arrival in Illinois, Dr. Emerson began campaigning for a transfer. He was not immediately successful, but in 1836 the Army decided to abandon Fort Armstrong and Emerson was transferred further north to Fort Snelling on a bluff above the Upper Mississippi in the Wisconsin Territory (a site in what is present-day St. Paul, Minnesota). The Wisconsin Territory, like Illinois, prohibited slavery.

While working for Emerson at Fort Snelling, Dred met and fell for another slave stationed at the Fort, Harriet Robinson, who belonged to Major Lawrence Taliaferro, a nearby Indian agent. The major, who also served as the local justice of the peace, married Dred and Harriet at Fort Snelling's Round Tower (now the oldest surviving building in Minnesota). The couple would remain married for the rest of Dred’s life. They would have four children. Two children, both daughters, survived infancy and became parties in the Scotts’ suit for freedom.

Dr. Emerson complained about the winter weather and requested a transfer back to St. Louis, which he received in the fall of 1837. But when he arrived back in St. Louis, leaving Scott behind at Fort Snelling to work for another officer, new orders sent him on to Fort Jesup in western Louisiana. The doctor soon concluded that his new post was much worse than Fort Snelling, which by now he called the “best post” in the country. He took time off from his complaining, however, to marry Eliza Irene Sanford of St. Louis in February 1838.

After his marriage, Emerson sent word that he wanted Dred and Harriet Scott transported down to his post in Louisiana. They made the journey mostly by steamboat. Little is known of their short stay at Fort Jesup.

By September 1838, Emerson had been transferred again and was making his way back north to Fort Snelling. Together with the Scotts, Emerson rode up the Mississippi on the stern wheeler Gypsy, arriving at the Fort in late October. Somewhere on the riverboat journey, north of the Missouri line, Harriet gave birth to the couple’s first child, Eliza.

Fort Snelling in the Wisconsin Territory (present-day St. Paul, Minnesota)

Emerson’s stay at Fort Snelling would be cut short, however. The doctor, apparently, got into an argument with the quartermaster over whether the Scott’s should be provided with a stove. When the quartermaster refused, a fight ensued, resulting in Emerson’s glasses being broken. He returned to the scene later waving two pistols, according to the story—all of which was too much for the post commander, who placed Emerson under arrest. In 1840, Emerson was ordered off to Florida, where the Seminole War was making things messy. The Scotts traveled with Emerson as far as St. Louis, where they were dropped off and either employed by Emerson’s wife or hired out. It seems very likely that at this time Dred Scott renewed his relationship with the Blows.

In 1842, the Army gave Emerson an honorable dismissal from the service. He returned to St. Louis for a brief time and then moved to Davenport in the Iowa Territory, where he began offering medical services and, while living in a hotel, started construction on a house. The Scotts, meanwhile, remained in St. Louis.

In December 1843, Dr. Emerson died, most likely of syphilis. His will made his wife, Irene Emerson, the holder of an estate for life, with his daughter, Henrietta, designated to take ownership of his property upon Irene’s death. Shortly after Emerson’s death, the Scotts seem to have been loaned to a brother-in-law of Irene’s, Captain Bainbridge. For the next three years, the Scotts served Bainbridge, who moved from the Jefferson Barracks to Fort Jesup in Louisiana, and finally to a post in Corpus Christi, Texas. When war broke out with Mexico, Captain Bainbridge sent the Scotts back to St. Louis, where Irene Emerson hired them both out to a man named Samuel Russell.

Soon after beginning work for Russell, Dred Scott would set in motion legal action that would ultimately change the course of the nation’s history.

Dred and Harriet Scott’s Suits for Freedom

Scott tried to purchase freedom for him and his family from Irene Emerson, but for unknown reasons, she refused. In April 1946, Scotts filed suit in St. Louis circuit court for the freedom of themselves and their two daughters, Eliza and Lizzie. Despite some the suggestion of some historians to the contrary, there is little or no evidence that the suit was brought to serve broad political goals; the Scotts (probably after having discussions with the Blows and other sympathetic acquaintances) simply wanted to be free. Harriet, it is believed by most historians, was the driving force behine the lawsuit. Dred and Harriet's eldest daughter, Eliza, had recently turned 8, an age at which slave children could be sold, but no sale could take place while her suit was being litigated--strong incentive for the couple to sue for their freedom. It is likely that Taylor Blow provided financial support for the litigation. The complaint claimed Emerson had “beat, bruised, and ill-treated” Scott, and that Scott was a free person wrongly held in slavery, and claimed damages of ten dollars.

Irene Emerson, owner of Dred and Harriet Scott in 1846

In 1846, a lawyer might have told Dred that the prospects for a successful suit looked good. The Missouri Supreme Court had heard over ten cases raising the issue of whether residence in a free jurisdiction had the legal effect of giving slaves their freedom—and in each case the slave’s right to freedom had been upheld. Missouri law could hardly have been more in Dred’s favor.

But in June 1847, at the “Old Courthouse” in St. Louis, the Scotts lost their case, not because of the law, but because of a technicality. The suit was brought against Irene Emerson, but the Scotts failed to produce a single witness who testified that Emerson actually owned them. Samuel Russell testified that he had paid money to Irene Emerson in return for Scott’s service, but on cross-examination admitted that his wife had made all the arrangements. Henry Blow testified that his father, Peter Blow, had sold Dred to Dr. Emerson years ago, but that hardly established Irene Emerson’s current ownership. Thus, the jury, after a one day trial, found for Emerson. The Scotts were returned to Emerson—a result that seems somewhat absurd given the basis for doing so.

Old St. Louis Courthouse, site of the Dred Scott trials

The Scotts filed a motion for a new trial, and in December 1847, the motion was granted by Judge Alexander Hamilton. Irene Emerson’s counsel objected to the order for a new trial, and the case headed up to the supreme court of Missouri. In April 1848, the court found no error in the decision to order a new trial, and the case was sent back to the trial court. Attorneys for Emerson moved to have the sheriff take charge of the Scotts and hire them out, and Judge Hamilton granted the motion. The effect of granting Emerson’s motion was to make her eligible to receive the accumulated earnings if a verdict was ultimately returned in her favor.

A year and half passed before the second trial opened, likely owing both to court delays and the fact that St. Louis experienced both a cholera epidemic and a severe fire in the intervening months. This time, the Scotts presented clear evidence that Irene Emerson was their purported owner. The defense presented evidence that Emerson had taken the Scotts to Fort Armstrong and Fort Snelling in service of the military—and then tried to argue (despite strong precedent to the contrary) that civil laws in Illinois and the Wisconsin Territory did not apply to people under military jurisdiction. The judge was unimpressed by this argument, and so was the jury. The jury sided with the Scotts.

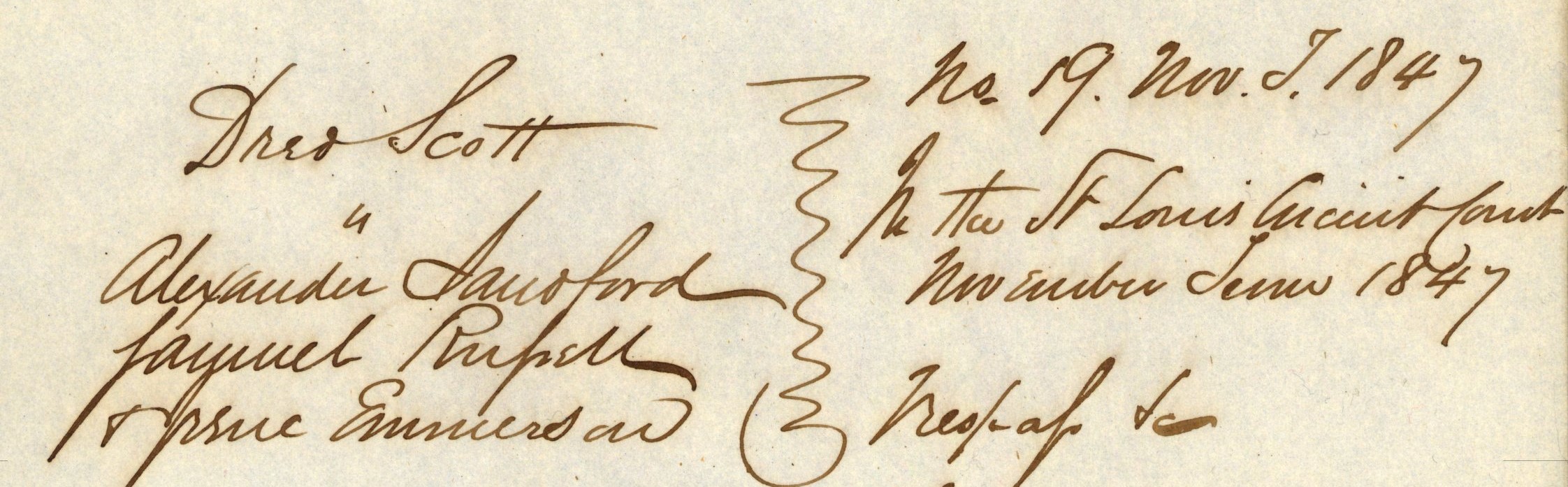

November 7, 1847 court filing: Dred Scott v Irene Emerson and two others

But Emerson appealed to the state supreme court. And there, after another long delay, the court handed down a decision in 1852 reversing the lower court and holding the Scotts to still be slaves. The law hadn’t changed, but the court and circumstances had. Two of the three judges on the court were strong proslavery Democrats. Slavery was now a hot button issue in Missouri. In reversing the lower court, the state supreme court overturned nearly three decades worth of precedent. Writing for the court, Judge William Scott declared, “Times are not now as they were when the former decisions on this subject were made.” Scott said “a dark and fell spirit” had taken hold in some individuals and states in relation to slavery. It was not in Missouri’s interest, he said, “to show the least countenance to any measure which might gratify this spirit.” From now on, Scott announced, the laws of free states would not be given legal weight or effect in these cases in the state of Missouri. Missouri will “assume her full responsibility for the existence of slavery.”

Scott v Sanford

Normally, that would have ended matters, except for a few formalities to be taken care of by the trial court. Emerson’s attorneys move to terminate the sheriff’s custody of the Scotts, a motion which, if granted, would have cleared the way for Emerson to receive payment of the wages earned by the Scotts for their hired-out work. But the judge denied the motion, saying that he would continue the case “awaiting decision of the Supreme Court of the United States.” Apparently, the judge had been told by attorneys for the Scotts of their intention to appeal.

John Sanford

The case remained in limbo for over a year. Meanwhile, the Scotts acquired new legal counsel and became the property of a new owner. Irene Emerson seemed to have sold (there is some debate about this still) the Scotts to her brother, John Sanford. (Although “Sanford” is the proper spelling, the famous Supreme Court decision will identify the defendant as “Sandford.”)

Sanford was a resident of New York City. Scott was a resident of Missouri. And under Article III of the Constitution, suits between citizens of two different states can properly be heard in federal court. So to federal court Scott’s lawyer, Roswell Field went. Dred Scott sued Sanford on November 2, 1853 in the U.S. Circuit Court for battery and wrongful imprisonment. He asked for $9,000 in damages.

Roswell Field, lawyer representing Dred Scott

Any good lawyer of the time had to be skeptical of Scott’s chances. Supreme Court precedent from 1851 (Strader v Graham) gave a greenlight to slave states to decide whether it would respect the laws of free states. Moreover, the Supreme Court had recently moved in a decidedly conservative direction, with a solid majority of slavery-supporting southerners on the Court. So it is a bit of a mystery why the money spent litigating the issue of the Scott’s freedom wasn’t spent instead purchasing his freedom.

Sanford responded to Scott’s filing with a plea in abatement challenging the jurisdiction of the court to hear the case. Sanford argued that Scott descended from slaves of “pure African blood,” and therefore was not a citizen of Missouri for constitutional purposes. If Scott was not a citizen, there was no diversity of citizenship, and the court had no authority to hear the case.

The trial judge ruled in the Scotts’ favor on the jurisdictional issue. Judge Robert Wells said that Scott was at least enough of a citizen to be covered by the diverse-citizen clause of the Constitution, whether or not his rights were co-extensive with white citizens. Even aliens had been allowed to bring suits in federal courts, the judge noted. He also pointed out that if an African-American could not sue, that meant also that he could not be sued.

Counsel for the two sides reached an agreed statement of facts and the case came to trial on May 15, 1854. Because of the stipulated facts, neither side bothered to call witnesses or introduce additional evidence.

Judge Wells told the jury that the case law was in Sanford’s favor. (Though he later said, privately, that he wished it were not.) The Missouri Supreme Court had decided that residence on free soil did not make Scott free, and the U. S. Supreme Court case law supported the right of Missouri to make that decision. The jury returned a verdict in Sanford’s favor.

New lawyers stepped in to take the case titled Dred Scott v Sandford to the Supreme Court. Henry Geyer, a pro-slavery U.S. senator from Missouri, and Reverdy Johnson of Maryland, a nationally known expert on constitutional issues and former attorney general under President Zachary Taylor, agreed to represent Sanford. Montgomery Blair, a well-connected Washington lawyer, agreed to represent Scott for free. (Blair would later become President Lincoln’s postmaster general and was called “the best read man in Lincoln’s cabinet.” Blair’s home, called the Blair House, remains an important gathering place today for the who’s who of Washington.)

The Supreme Court heard four days of oral argument on the case in February 1856. It was a tumultuous time in America. Kansas seemed on the verge of Civil War. The Kansas-Nebraska Act, which allowed the residents of new territories to allow slavery if they chose, was about to lead to the formation of a new political party opposed to the spread of slavery, the Republican Party. (The party was founded the next month in Ripon, Wisconsin.) Congress was engaged in a series of angry debates about its own power to regulate slavery in the territories. Dred Scott was now the pawn in a political game beyond his earlier imagining.

In their oral arguments for Sanford, Geyer and Johnson made a new argument. In addition to arguing that Dred Scott was not a citizen and therefore could not sue in federal court, they attacked the constitutionality of the Missouri Compromise that had prohibited slavery in territories north of Missouri’s southern border.

The direct constitutional attack on the Missouri Compromise got everyone’s attention. Soon newspapers were proclaiming it to be the most important case to be decided by the Court in a generation, if not of all time.

But it would be a while before the decision came down. The justices were divided on key issues. Majorities shifted. The Court decided to order the case argued again the next term. After twelve more hours of argument, the Court was finally ready to decide.

Chief Justice Roger B. Taney

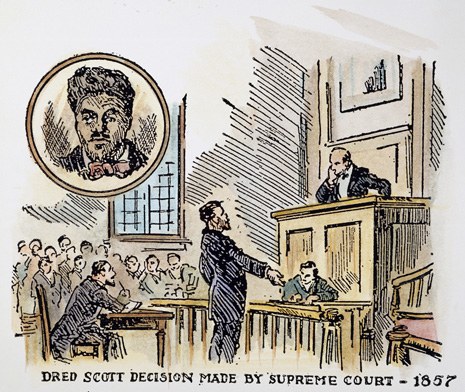

On March 6, 1857, in a crowded courtroom, Chief Justice Robert Taney announced the opinion of the Court. He read for two hours in an almost inaudible voice. The decision was confusing, with a number of concurring opinions and two dissenting opinions, but one thing was clear: Dred Scott had lost. He was still a slave.

Taking Taney at his word that he spoke for a majority of the Court, and that seems to be the most reasonable course given the history that followed, the Court drew the following conclusions: (1) the ruling of the lower court that Scott was still a slave was properly reviewable by the Supreme Court (if the conclusion were otherwise, that should have ended the discussion); (2) Negroes (the word almost universally used at the time to describe persons of African descent) were not citizens of the United States for constitutional purposes and therefore there was no “diversity of citizenship” between Scott and Sanford to provide federal jurisdiction; (3) Scott’s multi-year residence at Fort Snelling in the free territory of Wisconsin did not make him a free man because the Missouri Compromise restricting slavery in the northern territories was unconstitutional; and (4) Scott’s residence in the free state of Illinois did not make him a free man because Missouri had every right not to give extraterritorial effect to the law of Illinois regarding slavery. For these reasons, the case was sent back to the circuit court with instructions to dismiss.

It was an opinion that seemed almost angry in tone and amounted to a clean sweep for southern interests. It represented the first time in the Supreme Court’s history that it had used its power of judicial review to invalidate a major act of Congress.

Epilogue

If Taney thought his opinion would settle the slavery issue once and for all, he was sorely mistaken. While the southern press was thrilled with the decision, the Northern press and many northern politicians and religious leaders denounced Taney’s tortured legal reasoning. Frederick Douglas said, “Judge Taney can do many things,. . . but he cannot change the essential nature of things—making evil good, and good, evil.” For all practical purposes, many northern state courts and legislators largely rejected the idea that Scott v Sandford was binding precedent. At the national political level, the decision energized the new Republican Party and, with compromises taken off the table, pushed them to support stronger steps in the direction of abolition. Meanwhile, the decision helped spark a divide between northern and southern Democrats, a fact which contributed to the 1860 election of Abraham Lincoln.

In the court of history, Scott v Sandford came to be seen as a dreadful decision. Chief Justice Taney, after his decision was denounced and his reputation forever damaged, died on October 12, 1864. Many decades later, before he assumed the position of chief justice that Taney had once held, Charles Evans Hughes would call Dred Scott v Sandford “our great self-inflicted wound.”

Dred Scott was effectively reversed with enactment of the Civil War Amerndments. In 1865, the Thirteenth Amendment abolished slavery. Three years later, the Fourteenth Amendment made all people born or naturalized in the United States citizens. The Scott decision was dead as a door nail.

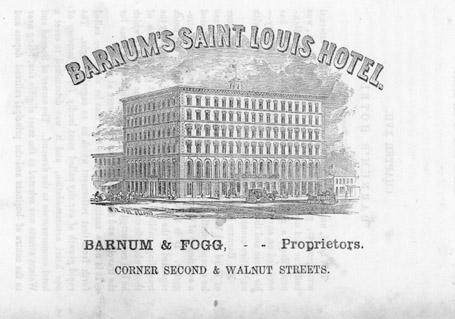

Barnum's Saint Louis Hotel, where Dred Scot worked after gaining his freedom

Shortly after the Supreme Court’s decision, in May of 1857, Taylor Blow purchased Dred and Harriet Scott and formally manumitted them. He took at job as a porter at Barnum's Hotel in St. Louis. Dred Scott became something of a celebrity. He told a reporter that his lawsuit brought him “a heap o’ trouble,” and that if he had known “it was gwine to last so long,” he never would have brought it. According to the reporter’s story, Scott was nonetheless “hugely ticked at the idea of finding himself a personage of such importance.” He “laughs heartily when talking of ‘de fuss dey make ‘dar in Washington ’bout de ole nigger.’” The reporter observed that while Scott was illiterate, he had a great deal of common sense, probably enhanced by his many travels. Scott told the reporter, with a grin, that he might make thousands of dollars touring around the country and telling his story.

Dred Scott died of tuberculosis on September 18, 1857. His wife, Harriet, lived almost another twenty years, dying in 1876.