by Douglas O. Linder (2019)

He called his invention “the thanatron.” It was an inexpensive contraption. A jewelry chain, parts from an Erector Set, an old motor, an intravenous line, and three plastic bottles. One of the bottles contained a saline solution, another a barbiturate called Seconal, and a third potassium chloride. Each of the three bottles connected to the IV line.

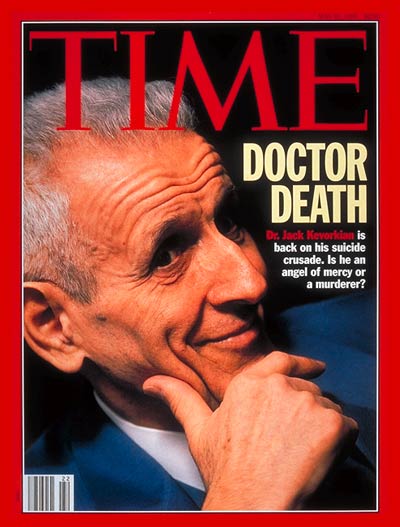

The inventor of the thanatron was 60-year-old doctor named Jack Kevorkian. The aim of his machine was to cause death. A humane, painless death.

To accomplish the goal, Kevorkian would first open the saline drip. Then, the patient to whom the IV line was attached would flip a switch. That flip would start a flow of Seconal for 60 seconds. Enough to put the patient in a deep coma. The flipped switch also started a winding process, acting like a timer, which would open the flow of the potassium chloride after the flow of Seconal stopped.

Potassium chloride stops the heart. It is the same solution that is delivered in the final step of most lethal injection procedures.

DR. JACK KEVORKIAN WITH HIS THANATRON

Kevorkian hoped to advertise the thanatron in local newspapers. If people knew about his machine, many would want to use it. Kevorkian had seen a lot of suffering in hospitals and nursing homes. And he believed that people with painful medical conditions should have the right to end their lives.

The newspapers turned him down. But his request to advertise a suicide machine struck some editors as newsworthy. And soon Dr. Kevorkian was attracting attention.

In 1989, several people who read about Dr. Kevorkian’s machine in Newsweek decided to contact him. One of those people was a 54-year-old teacher from Portland, Oregon named Janet Adkins. Janet had led an active life. She climbed Mount Hood, trekked in Nepal, hang glided, and raised a family. But she was suffering from early onset Alzheimer’s disease.

Doctors told Adkins and her husband that she could live for many years. But she didn’t want to—and she worried that if she waited too long, she wouldn’t be able to communicate her wishes. So Janet and Ron Adkins flew to Michigan to see Dr. Kevorkian.

Kevorkian believed in his cause. He didn’t want anyone questioning his motives and made clear that he would accept no payment for his services. Also, he understood that minds can change when it comes to an important question like ending one’s life. He insisted that any patient must express “a firm, voluntary, and unwavering wish to die.”

Kevorkian met four separate times with Janet and Ron. He recorded three of those interview sessions. He discussed with them Janet’s medical history and her prognosis. He insisted that Janet and Ron fill out a seven-page questionnaire. Finally, he explained exactly how his suicide machine would work.

When it became clear that Janet Adkins was adamant about her desire to die, Kevorkian began looking for a place to put his thanatron into action. Jack lived in an apartment and worried that his landlord would evict him once it became known how he was using it. He asked funeral homes and hotels if they would be willing to host the event, but—unsurprisingly—none was interested. Eventually he settled on using his 1968 Volkswagan van. He bought curtains for the windows and installed a cot.

DR. KEVORKIAN'S "DEATH VAN"

Kevorkian and his sister Flora went to Janet’s hotel. Janet said goodbye to her husband. The three drove to a nearby campground. Kevorkian hooked Janet up to a heart monitor and attached an IV line from the thanatron to her arm. Janet’s last word was, “Hurry.” Kevorkian replied, “Safe journey.”

When the monitor showed a flat heart rate, Jack called the police. He was arrested and placed in jail—but not for long. As it turned out, there was no law in Michigan prohibiting assistance with a suicide.

The day after Janet’s death, her husband Ron held a press conference in Portland. Adkins read a statement that he said was written by Janet shortly before she ended her life. She wrote, “I have Alzheimer’s disease and I do not want to let it progress any further. I do not want to put my family or myself through the agony of this terrible disease.”

A reporter for the New York Times interviewed Kevorkian. Jack was quoted as saying, “My ultimate aim is to make euthanasia a positive experience. I’m trying to knock the medical profession into accepting its responsibilities.”

The same story quoted a medical ethics professor. She said there was a thin but significant line between withdrawing medical care and aiming to cause death. But she admitted that some doctors crossed the line, albeit carefully. She gave the example of an oncologist who might tell a cancer patient, “Here’s some medication, but make sure you don’t take more than 22 pills because 22 pills will kill you.”

Janet Adkins was the first. But before Dr. Kevorkian was done, more than 130 people would obtain his help in ending their lives. Not all of his patients—if that is the right word—were terminally ill. In fact, a study by the Detroit Free Press indicated that only about 40% of Kevorkian’s patients had been diagnosed with a terminal illness. The Free Press also reported that at least five of his patients had histories of depression. Finally, the study suggested that Kevorkian sometimes failed to follow even his own guidelines. At least 19 of his patients died less than 24 hours after first meeting with Kevorkian.

If the Free Press study is accurate—and it seems to be—then it’s fair to conclude that Dr. Kevorkian believed that clear-headed adults should have the right to choose death. Period. Incurable diseases and pain and suffering might often be the reason for such a choice; but Kevorkian seems to have been willing to accept a range of other reasons as well.

By the end of 1991, after just the first three of Kevorkian’s many assisted suicides, Michigan suspended his license to practice medicine. The Board of Medicine’s vote was 8 to 0. They said it was important to send a message that Kevorkian’s actions were completely unacceptable.

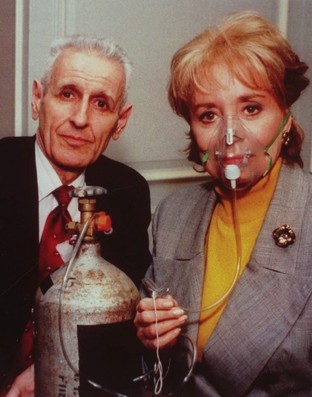

After his license was suspended, Kevorkian could no longer legally obtain the drugs for his Thanatron. His new method of choice was to place a mask over his patient’s nose and mouth. A tube connected the mask to a cylinder of carbon monoxide. The patient started the flow of the gas by releasing a valve. Death would take longer than it did with his thanatron, up to ten minutes or more. He called his new device “the mercitron.”

BARBARA WALTERS TRIES OUT THE "MERCITRON"

Dr. Kevorkian had become the man to see if you wanted help ending your life. And Michigan authorities were not happy about it. By the end of 1992, with Kevorkian’s death toll mounting, the state decided to act. On December 15, Michigan Governor John Engler signed a law making it a crime to assist in a suicide.

Thomas Hyde was only 30 years old. But his body had already been ravaged by ALS, Lou Gehrig’s disease. He was unable to walk, slurred his speech, couldn’t control bodily functions, and had difficulty swallowing. Attending an ALS support group only made things worse—he saw only more clearly the horrible fate that awaited him. Before his diagnosis, Hyde had been an active outdoorsman. He couldn’t stand it anymore.

Hyde contacted Dr. Kevorkian and the assisted suicide took place in Kevorkian’s van behind his apartment in August 1993.

One month later, Kevorkian was charged with murder. The law made it a crime to “knowingly provide the physical means or participate in the act of suicide.” But the law excluded acts when the “intent is to relieve pain.”

Geoffrey Fieger, Kevorkian’s brash and flamboyant defense lawyer, delivered the opening statement. He told jurors, “You will decide how much suffering all of us must endure before we go into that good night—some of us, not gently.”

The trial lasted five days. The most emotional moment came when the jury watched a videotape. Hyde struggled to make his wishes known, in words that could barely be made out: “I want to end this; I want to die.” Many jurors cried as they watched.

For Kevorkian, the trial seemed like a farce. “I am only going along with it to make Geoffrey feel good,” he said at one point. A reporter for Vanity Fair noted that Jack spent much of the trial studying vocabulary lists of Japanese verbs.

Fieger argued that the law did not apply to Kevorkian because his aim was always to eliminate suffering, and that death was a mere consequence of his goal. The jury seemed confused by the law.

The jury deliberations lasted nine hours. Jack, in his maroon sweater, kept a bemused look as the jury filed in to deliver the verdict: “Not guilty.”

One juror said afterward that Kevorkian’s own passionate statements about his desire to end Hyde’s suffering carried the day. “He’s not a murderer,” she said. Another juror told a reporter, “I don’t feel it’s our obligation to choose for someone else how much pain and suffering they can go through. That’s between them and their God.”

Defense attorney Fieger said the jury’s decision “drove a stake” through the state’s law. He said the jury vindicated the right of “every person in this country and in this state who is suffering from” a terrible disease such as ALS.

Even the prosecution acknowledged they had chosen a tough case. It was just a matter of time before Hyde would have choked on his own saliva. Prosecutor Timothy Kenny said, “There were just an awful lot of emotional hurdles to get over in this case.”

A spokesperson for Michigan Right to Life worried about the effects of the decision. “That jury has just unleashed the floodgates. There is going to be no stopping him or other doctors who believe they are God.”

Over the next three years, Michigan would try to convict Kevorkian three more times.

In his second trial, Kevorkian was charged in connection with the deaths of a doctor suffering from bone cancer and a woman with ALS. Again, videotapes played a key role. Dr. Ali Khalili, a rehabilitation specialist, said on tape that the pain in his bone could not be relieved by morphine. On the tape, Jack asks the doctor why he didn’t commit suicide on his own. After all, he could have simply prescribed the pills that would do the job. Dr. Khalili answered, “Maybe I prefer that it be done by a professional person with the least chance of failure.”

An appeals court made Geoffrey Fieger’s job a bit tougher in this second trial. They ordered the trial judge to tell jurors that the state need not prove that Kevorkian’s “sole intent” was to cause death. Having a primary intent of ending suffering should not be enough to save him.

But the jury saw it differently. They acquitted Kevorkian.

Kevorkian’s third trial was his toughest test yet. Once more, he was charged for two deaths, but this time neither individual was suffering from a terminal illness. Marjorie Wantz suffered from MS, but doctors said she still had a long life ahead of her. Sherry Miller, just 43, was in constant pain from a series of botched surgeries.

In this third trial, the state charged Kevorkian not with violating a statute, but rather common law. In December 1994, the Michigan Supreme Court ruled that assisting suicide, even in the absence of a statute, had always been a crime. And a ruling by the Michigan Court of Appeals all but mandated a conviction. It said the jury must convict if the state proved that Kevorkian “by some act assisted” the suicide.

KEVORKIAN (WITH FIEGER) PROTESTING BEING TRIED UNDER COMMON LAW

The notion of common law crime didn’t sit well with Kevorkian. To protest the dredging up of a law said to date back centuries, he wore colonial dress at the start of trial—a powdered wig, knee breeches, and black buckle shoes. On the witness stand he shouted, “There ain’t no law. I only recognize laws passed by the legislature, not made up by courts.”

It took a while for the jury to reach its decision. For the first time, Kevorkian seemed worried. Four jurors initially voted to convict. But, in the end, it was another win for Kevorkian and Fieger. “The jury saved me,” Kevorkian said. He seemed deeply moved by the decision.

The jury foreman said the jury had “reasonable doubts.” None of the jurors seemed bothered by the fact that neither of the women was terminally ill. But several said they were troubled by the idea of judge-made crimes. One juror said that she came to a realization while raking leaves in her yard the weekend before their deliberations. “I didn’t want someone to come along three years from now and say that raking leaves back then was illegal, you just didn’t know it.”

Geoffrey Fieger was a happy man. He said, “This will be the last Kevorkian trial.” He accused the prosecution and certain judges of trying to stack the deck against his client. “Thank God for the jury system,” he said.

GEOFFEY FIEGER

Dr. Kevorkian told reporters, “While this may be a sin to you, one thing is clear. For any enlightened human being, this can never be a crime.” He declined an offer to attend a victory celebration. “It’s my poker night,” he explained.

After three acquittals, and a fourth case that ended in a mistrial, it seemed likely that no Michigan jury would ever convict Kevorkian for participating in a suicide. After three years without prosecution, assisted suicide had fallen out of the headlines. Jack was determined to push his crusade further. He was itching for a fight.

Thomas Youk was a race car driver, champion of the Ohio Valley circuit. In 1996, his career came to an end when he was diagnosed with ALS. By 1998, he had a food tube in his stomach; his lung capacity was a small fraction of normal; he was all but completely paralyzed. He told his brother that his pain was like having his body plugged into an electric socket.

Tom asked his family to contact Dr. Kevorkian. They found his address on the internet and sent him a letter. Jack called the family back the next day and arranged a visit.

In the Youk family living room, Kevorkian set up a video camera. Jack put Tom’s hand into his own and asked him to describe what ALS had done do him. Then Jack asked Tom to attempt a series of movements—for example, “try lifting your left hand off of your wheel chair.”

Kevorkian described the procedure he would use to end Tom’s life. After hearing a description of the procedure that would end his life, Tom read a consent form. It said that he agreed to use “active euthanasia to be administered by a competent medical professional in order to end with certainty my intolerable and hopelessly incurable suffering.”

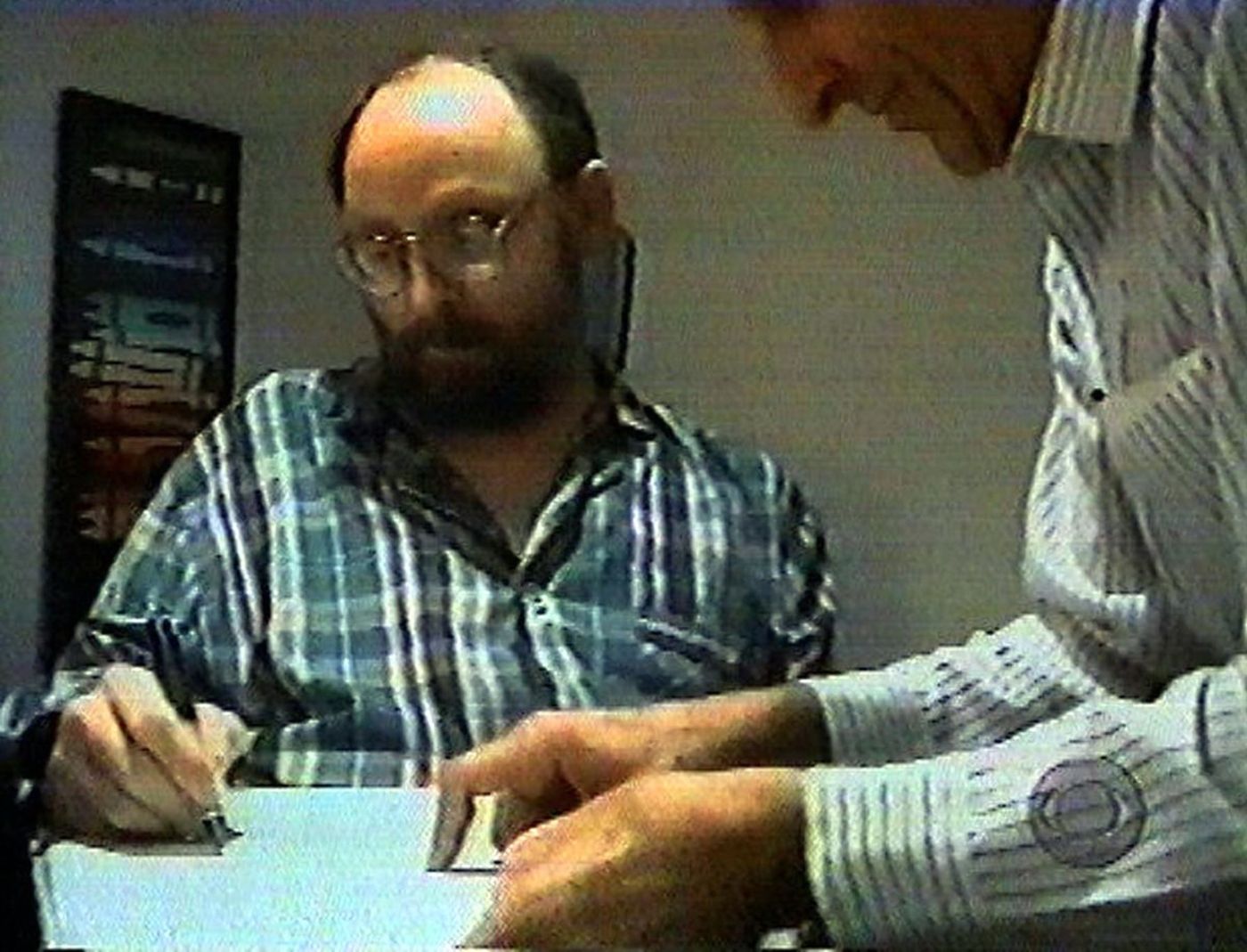

THOMAS YOUK SIGNS CONSENT FORM

Kevorkian asked how long Youk could wait until the procedure. He agreed he could hold out for another week. “OK,” Jack said, “let’s not hurry into this.”

Kevorkian left, went home, and settled into listen to classical music. Jack loved music. He produced a jazz CD in 1997 called “A Very Still Life” that was nominated for a Grammy Award.

The next afternoon, Kevorkian received a call from Youk. He couldn’t wait any longer. He wanted to end his suffering now. Jack headed over to the Youk home with his equipment—including his video camera.

Kevorkian turned on the camera and started an intravenous line. “Are you sure you want to go ahead now?” Jack asked. Tom nodded. Jack injected Seconal into Youk’s right hand. Because Jack took the action that would cause death, Youk’s death would not be an assisted suicide, it was euthanasia.

Youk gasped, and his chin fell to his chest. “Are you awake? Jack asked. No answer. Kervorkian proceeded to inject a lethal dose of potassium chloride. Then he eyed the electrocardiogram until it showed a straight line. The whole procedure took less than five minutes.

Kevorkian wanted to take a stand. He publicly begged to be prosecuted. He called Mike Wallace of the CBS show 60 Minutes and arranged to have his videotapes of the Youk interview and death sent to the network.

On November 22, 1998, 60 Minutes broadcast the segment on Kevorkian. Jack watched the broadcast with friends and was thrilled. In the interview, Wallace asked Jack whether what he did to Youk could be called “murder.” Jack said, “It could be manslaughter, not murder. It’s not necessarily murder, but it doesn’t bother me what you call it.” Jack said that what Youk got “was better than an assisted suicide” because there was “better control” when he administered the drug himself.

Wallace asked Kevorkian, “You were engaged in a political, medical, macabre publicity venture, right?” Jack’s reply was, “Probably.” “Maybe it is ghoulish,” he admitted. Kevorkian challenged prosecutors to try him. He promised that if convicted, “I will starve myself to death in prison.” It was time to decide once and for all whether what he was doing was right. Jack said, “The issue has got to be raised to the level where it can finally be decided.”

Jack believed that he was taking a stand for liberty. “If you don’t have liberty and self-determination,” he told Wallace, “you have nothing. That’s what this country was built on … You try to take a liberty away from me, and I turn fanatic … I’m fighting for me. Now that sounds selfish. And if it helps everyone else, so be it.”

Three days later, Michigan prosecutors charged Kevorkian with first-degree murder and aiding and abetting a suicide.

Geoffrey Fieger thought the 60 Minutes videotape was damaging. Apart from the potentially damaging admissions relating to Youk's death, Kevorkian had offered a host of controversial opinions in the interview on subjects ranging from religion to the Supreme Court to abortion. Likely unhelpful, from the standpoint of winning over jurors, was Jack's assertion that his "god" (Johann Sebastian Bach), unlike God as worshipped by most Americans, was not "invented." He compared American hospitals to Nazi concentration camps and called the Supreme Court "corrupt." The taped interview also featured clips of courtroom outbursts and samples from his collection of graphically violent art. Feiger told Jack he would try to get the tape excluded from evidence. But Jack no longer wanted to hide anything. He was proud of the tape and he didn’t care if it helped the prosecution. Fieger told Kevorkian that, as a lawyer, he could not allow his client’s case to self-destruct. The “consider yourself fired,” Jack told him.

Kevorkian’s fanaticism blew away his common sense. He talked to his new lawyers about getting convicted and taking the question of euthanasia to the U. S. Supreme Court. He told them he was willing to sacrifice his freedom for the cause. He even suggested he might win the Nobel Prize.

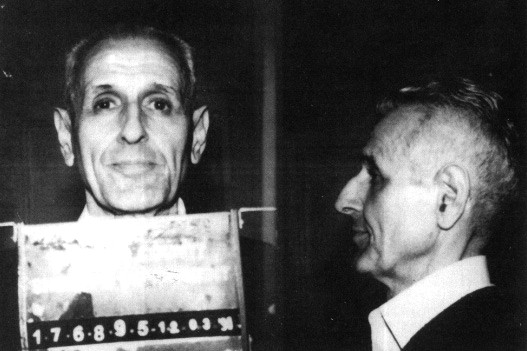

KEVORKIAN AT HIS ARRAIGNMENT IN 1999

His new lawyer was no Geoffrey Fieger. In a big legal blunder, the lawyer made a motion to dismiss the charge of assisted suicide. The lawyer’s theory was that no jury would ever convict Jack of murder. If assisted suicide was off the table, they would have to choose between a murder conviction and a full acquittal.

The trial judge, Jessica Cooper, warned the lawyer of the consequences of dismissing the assisted suicide charge. Without that charge standing, any evidence about the pain and suffering of Thomas Youk would be irrelevant and legally inadmissible. With that opinion of the judge on the record, the prosecutor on his own motion dismissed the assisted suicide charge.

The trial was an utter disaster. Kevorkian represented himself. He was warned against it by Judge Cooper, but it was his right to do so. “Do you realize you could spend the rest of your life in prison?” Jack replied, “There’s not much of it left, your honor.”

The only argument he made was that euthanasia should be legal. But it wasn’t. The prosecution had the videotape—and the videotape was not good. On tape, Jack seemed at least as concerned about himself as he did his patient.

Outside, both supporters and opponents of Kevorkian gathered. More than once, vanloads full of disabled people would pull up. Some would roll out in their wheelchairs, others lie down by the steps of the courthouse. Advocates for the disabled shouted through bullhorns, “Hey, hey, ho, ho, Doctor Death has got to go!”

The trial lasted just two days. Jack didn’t call a single witness. In his closing argument, he compared himself to Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King—a champion for civil liberties.

The jury found Kevorkian guilty of second-degree homicide.

Thomas Youk’s wife wrote the judge a letter. She wrote that her husband was grateful for Kevorkian’s assistance and asked that he be given “clemency.” Judge Cooper sentenced Jack to serve 10–25 years in prison. In pronouncing the sentence, here’s what she told Kevorkian:

“This is a court of law and you said you invited yourself here to take a final stand. But this trial was not an opportunity for a referendum … You invited yourself to the wrong forum. Well, we are a nation of laws ... We have the means and the methods to protest the laws with which we disagree. You can criticize the law, you can write or lecture about the law, you can speak to the media or petition the voters.”

But, she told Kevorkian, the method he had chosen to protest the law was not one that the Constitution protected. “You had the audacity to go on national television, show the world what you did, and dare the legal system to stop you. Well, sir, consider yourself stopped.”

KEVORKIAN AND JUDGE JESSICA COOPER IN THE YOUK TRIAL

Kevorkian served his time in a prison in Coldwater, Michigan. In a 2004 interview with a reporter for the New York Times, Jack said that he regretted representing himself in his trial, a decision he attributed to his arrogance. In an MSNBC interview aired in 2005, Jack said that if he were freed from prison, he would no longer directly help people die. Instead, he would limit himself to campaigning to have the law changed.

After being paroled for good behavior in 2007, Kevorkian launched a campaign for Congress against the Republican incumbent. In the multi-candidate race, Kevorkian received 2.6% of the vote. He died in 2011, at age 82. According to his attorney, there were no artificial attempts to keep him alive and his death was painless.

The cause that Dr. Jack Kevorkian fought for lives on. Polls show a nation deeply divided on the issue. A Pew Research poll indicates 46% of respondents support physician-assisted suicide and 45% oppose.

State laws generally prohibit the practice. The exception is Oregon—where in 1994, voters approved the so-called “Death with Dignity Act” by a margin of 51% to 49%. The US Supreme Court considered a challenge to the law in 2006. By a 6 to 3 vote, the Court held that the U.S. Attorney General cannot enforce the federal Controlled Substances Act against physicians who, in compliance with Oregon state law, prescribe drugs to terminally ill patients seeking to end their lives.

The Supreme Court has also considered right-to-die issues in two other cases.

In 1990, the Court weighed the fate of Nancy Cruzan. On a January night in 1983, Nancy’s car spun off a rural Missouri road. The car flipped and ended up 35 feet from the road. Oxygen was cut off to Nancy’s brain and she lapsed into a vegetative state from which she never recovered.

Four years later, Nancy’s parents requested that medical staff withdraw the feeding tube that was keeping her alive. When hospital authorities refused to comply with their request, Nancy’s parents filed suit. Nancy, of course, was in no position to express her own desires. Her parents said that Nancy would never want to exist like she did. They argued they had the right to make the decision for her. A trial judge agreed with the Cruzan’s, but the State of Missouri appealed.

The state argued that Missouri could insist on "clear and convincing evidence" of a comatose patient's desire to terminate her life before allowing doctors to carry out a family's wish to disconnect the patient from life support.

Eight of the nine justices in the Cruzan case agreed that the right to die was a liberty protected by the Due Process Clause.

Even so, a bare majority of the Court upheld the state's right to insist upon clear and specific evidence that the patient would want to have her intravenous feeding discontinued. Four dissenters would have allowed the feeding tube to be withdrawn based on the evidence presented at trial.

The Cruzan decision spurred considerable interest in "living wills," which clearly express an individual’s desire to discontinue treatment or feeding in specified circumstances.

There is an end to this story about Nancy Cruzan—“happy” is not exactly the right word for it. But it might have been the best end to a bad situation. It turned on the discovery of additional evidence of Nancy's wishes. Two witnesses testified that they had discussions with Nancy while she was feeding an older relative years before. They said Nancy called her relative “a vegetable” and said she would never want to live like that. Based on this new testimony, the court ordered her feeding discontinued.

Seven years after the Cruzan decision, the Supreme Court faced right to die issues again. This time they considered two cases involving challenges to laws that criminalized physician-assisted suicide. The lower courts in each case, one concerning a Washington state law and another a New York statute, found the laws unconstitutional. The Washington decision rested on right-to-privacy grounds, while the New York decision rested on equal protection grounds.

The Supreme Court reversed in both cases—concluding that laws against physician-assisted suicide are constitutional. Although the Court interpreted Cruzan as recognizing a right to refuse medical treatment, the Court found no constitutional basis for a right to assisted suicide. There was a critical difference, the Court said, between withdrawing treatment and taking an action that is aimed directly at causing death. A difference between what is sometimes called passive euthanasia (letting nature take its course) and active euthanasia.

Three justices in concurring opinions indicated that they might be willing to uphold "more particularized challenges" to such laws, such as an “as applied” challenge to a state's refusal to assist a terminally ill patient in severe pain from ending his or her life.

Philosopher Albert Camus had something to say about suicide. He said, “There is but one truly serious philosophical problem and that is suicide. Judging whether life is or is not worth living amounts to answering the fundamental question of philosophy. All the rest comes afterwards. These are games; the first problem one must answer.”

Camus is right in at least one sense. What more fundamental choice can we make than the decision to live or die? But should the choice be a protected liberty? It is a decision that can seriously affect others, most clearly the loved ones of those who choose suicide.

If choosing death should ever be a protected liberty, it most certainly should be so when the person who makes that choice is suffering severe and incurable pain. Time will tell whether the choice made by the people of Oregon to authorize physician-assisted suicide will be made the people of other states. My guess is that it will. And Dr. Kevorkian will have the last laugh, if that is what you could call it.