Mary Dyer's "Monster": Descriptions and Analysis

Note:

Mary Dyer was in the seventh month of her pregnancy when she began, on October 17, 1637, to have contractions. Mary’s close friend, Anne Hutchinson, was an experienced midwife. Hutchinson hurried to the Dyer home to assist with the delivery, accompanied by Goody Hawkins.

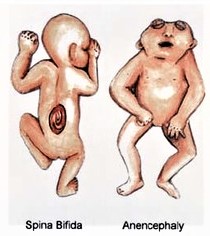

It was a long and difficult delivery. The baby was a girl—and stillborn. She was seriously deformed, with a face, but no skull. The modern description of anencephalia, together with spina bifida, fits almost perfectly with later descriptions of the malformations that appear in the writings of Governor John Winthrop. But to the Puritan mind, such deformities didn’t happen by accident—God was likely using “the monster” to send a message. And the message, Winthrop and others of his ilk would conclude, was that God was mightily displeased with Dyer, Hutchinson, and the other troublesome heretics rising in Boston.

Hutchinson and Mary’s husband, William Dyer, understood the need to keep the birth secret. Anne enlisted the help of her friend, the Reverend John Cotton. While William remained with his unconscious wife, Hutchinson, Hawkins, and Cotton wrapped the baby in a sheet, and in the dead of night buried her in the graveyard of Boston Church.

Mary’s secret would come out. In March, 1638, following Anne Hutchinson’s expulsion from the Church, Mary Dyer made a point of walking out of the church hand in hand with her friend. One of the onlookers called out, there goes “the mother of a monster!” The comment came to the attention of Governor Winthrop, who immediately launched an investigation which led to Goody Hawkins, and to John Cotton, who both hrevealed the details of the unfortunate birth. Winthrop could hardly wait to tell the world about it.

A Medical Analysis of the Dyer Childbirth (from "Such Monstrous Births": A Neglected Aspect of the Antinomian Controversy” by Anne Jacobson Schutte. Renaissance Quarterly, Vol. 38, No. 1 (Spring, 1985):

Anencephalia is "a malformation characterized by complete or partial absence of the brain and overlying skull," in which "the absence of the cranial vault renders the face very prominent and somewhat extended; the eyes often protrude markedly from their sockets." About 70% of anencephalics are female. If not stillborn, they die soon after birth. Since the head is abnormally small, breech presentations are common. Williams Obstetrics, 5th ed., ed. Jack A. Pritchard and Paul C. MacDonald (New York, 1976), pp. 829-3I. Goody Hawkins told Winthrop and his colleagues that Dyer's baby "came hiplings till she turned it." There is only a 4.5% chance of a woman's bearing more than one anencephalic; Dyer had one previous and six subsequent normal children. Gilbert W. Mellin, "The Frequency of Birth Defects," in Birth Defects, ed. Fishbein, pp. I2-1 5. The occurrence of anencephalia in the United States is .I77% among whites. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, Supplement 13 (1967), 30-34. The modern description of anencephalia accords perfectly with Winthrop's account of the gross malformations of the head, bony protuberances from which could easily have been seen as horns. The details he provided about the back point to a severe form of spina bifida, which often occurs in conjunction with anencephalia. Williams Obstetrics, p. 831. The three-clawed feet suggest Type V syndactyly, in which two or more toes are fused. Samia A. Temtamy, "Syndactyly," in Birth Defects: Atlas and Compendium, ed. Daniel Bergsma (Baltimore, 1973), p. 835 (#772).

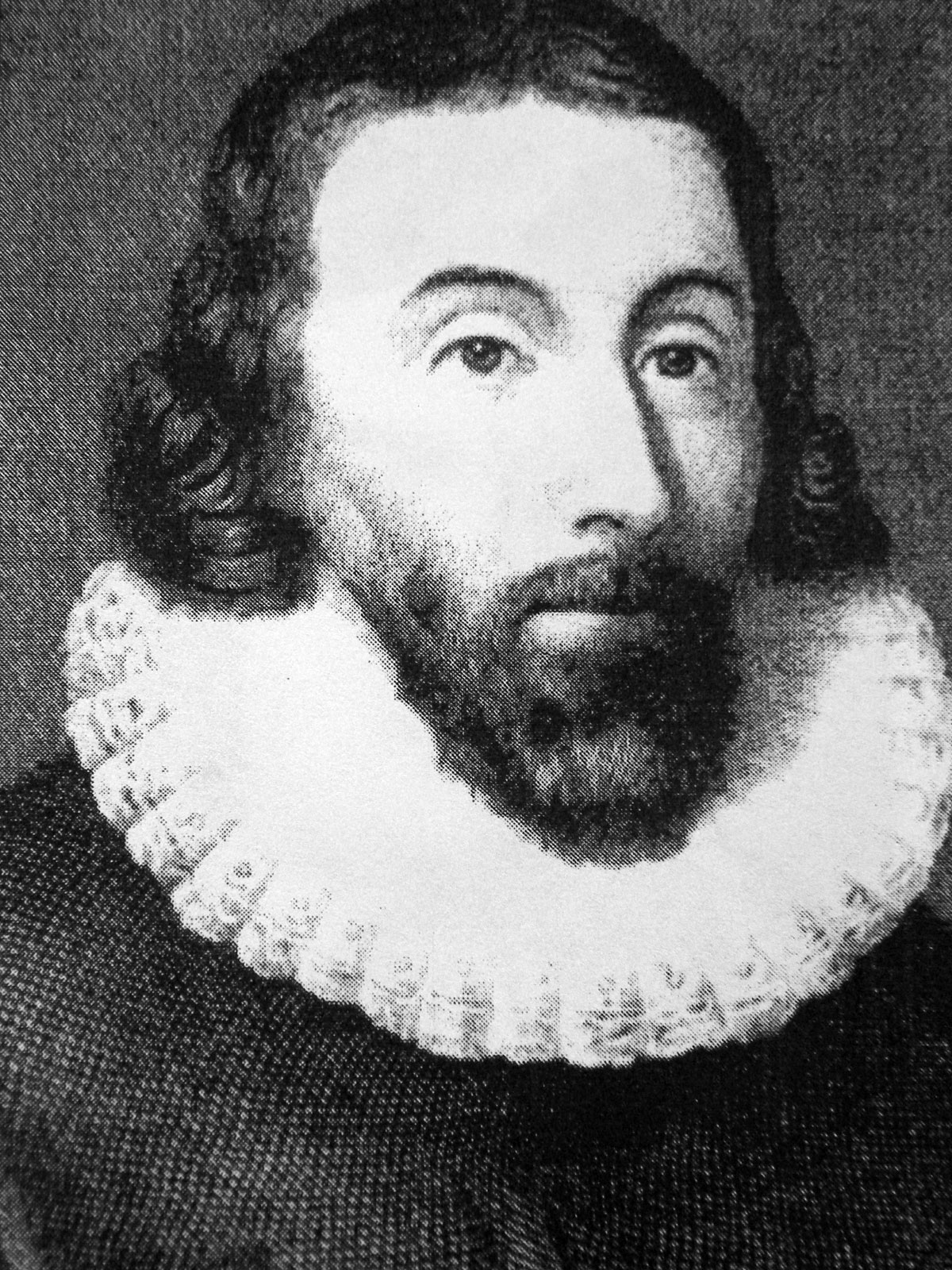

John Winthrop. “A Short Story of the Rise, Reign, and Ruine of the Antinomians, Familists & Libertines, that infected the Churches of New-England” (1644):

At Boston in New England, upon the 17 day of October 1637, the wife of one William Dyer, sometime a Citizen & Millener of London, a very proper and comely young woman, was delivered of a large woman childe, it was stilborn, about two moneths before her time, the childe having life a few houres before the delivery, but so monstrous and misshapen, as the like hath scarce been heard of: it had no head but a face, which stood so low upon the brest, as the eares (which were like an Apes) grew upon the shoulders.

John Winthrop. Winthrop's Journal: "History of New England", 1630-1649.

Governor John Winthrop

October 17 [1637], and the child buried, (being still-born,) and viewed of none but Mrs. Hutchinson and the midwife, a rank familist also [a follower of Mrs. Hutchinson]; and another woman had a glimpse of it, who not being able to keep counsel, as the other two did, some rumor began to spread, that the child was a monster.

One of the elders, hearing of it, asked Mrs. Hutchinson, when she was ready to depart; whereupon she told him how it was, and said she meant to have it chronicled, but excused her concealing of it till then, (by advice, as she said, of Mr. Cotton), which coming to the governor’s knowledge, he called another of the magistrates and that elder, and sent for the midwife, and examined her about it.

At first she confessed only, that the head was defective and misplaced, but being told that Mrs. Hutchinson had revealed all, and that he intended to have it taken up and viewed, she made this report of it, viz.: it was a woman child, stillborn, about two months before the just time, having life a few hours before; it came hiplings till she turned it, it was of ordinary bigness; it had a face, but no head, and the ears stood upon the shoulders and were like an ape’s; it had no forehead, but over the eyes four horns, hard and sharp; two of them were above one inch long, the other two shorter; the eyes standing out, and the mouth also; the nose hooked upward; all over the breast and back full of sharp pricks and scales, like a thornback; the navel and all the belly, with the distinction of the sex, were where the belly should be, and the back and hips before, where the belly should have been; and the back and hips before, where the belly should have been; behind, between the shoulders, it had two mouths, and in each of them a piece of red flesh sticking out; it had arms and legs as other children; but, instead of toes, it had on each foot three claws, like a young fowl with sharp talons.

The governor speaking with Mr. Cotton about it, he told him the reason why he advised them to conceal it: 1. Because he saw a providence of God in it, that the rest of the women, which were coming and going in the time of her travail, should then be absent. 2. He considered that, if it had been his own case, he should have desired to have had it concealed. 3. He had known other monstrous births, which had been concealed, and that he thought God might intend only the instruction of the parents, and such other to whom it was known, etc. The like apology he made for himself in public, which was well accepted …

The governor, with advice of some other of the magistrates and elders of Boston, caused the said monster to be taken up, and though it were much corrupted, yet most of those things were to be seen, as the horns and claws, the scales, etc. When it died in the mother’s body, (which was about two hours before the birth,) the whereon the mother lay, and withal there was such a noisome savor, as most of the women were taken with extreme vomiting and purging, so as they were forced to depart; and others of them their children were taken with convulsions, (which they never had before nor after,) and so were sent for home, so as by these occasions it came to be concealed.

Another thing observable was, the discovery of it, which was just when Mrs. Hutchinson was cast out of the church. For Mrs. Dyer going forth with her, a stranger asked, what young woman it was. The others answered, it was the woman which had the monster; which gave the first occasion to some that heard it to speak of it …

Another observable passage was, that the father of this monster, coming home at this very time, was the next Lord’s day, by an unexpected providence, questioned in the church for divers monstrous errors, as denying all inherent righteousness, etc., which he maintained, and was for the same admonished.

Edmund Browne's letter to Sir Simonds D'Ewes (September 7, I638) (the letter contains a description of Dyer's monster, obtained from Winthrop. Letters from New England: The Masschusetts Bay Colony, I629- I638, ed. Everett Emerson (Amherst, 1976):

The eyes stood farre out, so did the mouth, the nose was hooking upward, the brest and back was full of sharp prickles, like a Thornback, the navell and all the belly with the distinction of the sex, were, where the lower part of the back and hips should have been, and those back parts were on the side the face stood.

The arms and hands, with the thighs and legges, were as other childrens, but in stead of toes, it had upon each foot three claws, with talons like a young fowle.

Upon the back above the belly it had two great holes, like mouthes, and in each of them stuck out a piece of flesh. It had no forehead, but in the place thereof, above the eyes, foure homes, whereof two were above an inch long, hard, and sharpe, the other two were somewhat shorter.