"[T]he sonofabitching thief is made a national hero and is going to get off on a mistrial, and the New York Times gets a Pulitzer Prize for stealing documents...What in the name of God have we come to?" --President Richard Nixon (Oval Office discussion, May 11, 1973)

Background: The Pentagon Papers Study

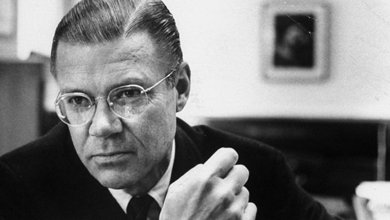

Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, growing concerned that the long war in Vietnam was unwinnable, first considered in late 1966 commissioning a study of the history of U. S. decision-making in Indochina. By June of the next year, the Secretary decided to proceed with the study, which McNamara said should be an "encyclopedic history of the Vietnam War." He believed, he later said, that a written record of the key decisions that led to the U.S. involvement in Vietnam would be of great value to scholars. Morton Halperin, one of McNamara's top aides, was chosen to direct the study. Much of the day-to-day responsibility for supervising the study was delegated to Leslie Gelb.

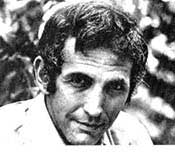

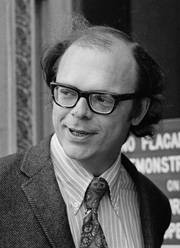

The McNamara study staff was given access to McNamara's personal files, memoranda from the White House and the Joint Chiefs of Staff, State Department records, and to specially requested information from the CIA. The frequently rotating professional staff for the study came from the Pentagon, the State Department, universities, and "think tanks" such as Rand. One of the first person recruited to help with the study was Daniel Ellsberg, a former Rand and Pentagon employee with six years of Vietnam-related experience. Ellsberg's work for the study focused on the Kennedy Administration's Vietnam policy in 1961.

In early 1969, the "Pentagon Papers" (formally, History of U.S. Decision-making in Vietnam, 1945-1968) study was complete. The massive work, examining Indochina policy from 1940 to 1968, consisted of 7,000 pages bound into forty-seven volumes. Pentagon officials classified the study "Top Secret" and published only fifteen copies. Although a historical study, officials worried that information contained in the Pentagon Papers, if it became public, would make foreign governments hesitant to engage in secret negotiations or provide secret assistance to the United States government. Officials also expressed concern that some of the information contained in the report came from wiretaps and bugging devices, and should the information be released it would likely jeopardize electronic surveillance and sensitive sources of information.

Daniel Ellsberg grew increasingly pessimistic about the chances of anything resembling a U.S. victory in Vietnam. The options, as he saw them, presented a choice between bad and worse. Shortly after the election of Richard Nixon as president in November 1968, Ellsberg was tapped to prepare a study of Vietnam "options" for Henry Kissinger, Nixon's newly-appointed national security adviser. In presenting his evaluation of options, Ellsberg found that Kissinger shared his negative assessment of the odds of a military victory. Ellsberg felt cautiously optimistic that Kissinger would help push Nixon to a policy of an early exit from the morass of Vietnam.

After meeting with Kissinger, Ellsberg returned to his work at the Santa Monica office of Rand, where he began reading the Pentagon Papers. As he read through the secret history of U.S. support for French efforts to crush independence movements in Indochina in the 1950s, Ellsberg came to see the continuation of the war in Vietnam as not just bad policy, but as immoral.

By mid-summer 1969, it became clear to Ellsberg that Nixon had no intention of simply declaring victory and pulling out of Vietnam. The president did not want to see the flag of the Vietcong fly over the city of Saigon. Faced with the prospect of a war without end, costing thousands of American and Vietnamese lives, Ellsberg pondered what he might do to bring about a change in U.S. policy. After attending an emotional conference of War Resisters at Haverford College in August, Ellsberg suddenly felt "liberated"--and ready to take action to end the war, even if it put himself at risk.

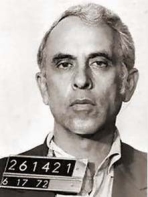

Convinced that release of the Pentagon Papers would make an already skeptical public more likely to apply the pressure that might finally bring an end to our involvement in Vietnam, Ellsberg decided to try to make that happen. When the public understood how it had been misled by past presidents, Ellsberg thought, they would no longer buy what the current president was telling them now. On September 30, 1969, Ellsberg visited the apartment of an anti-war friend of his, Anthony Russo. Ellsberg told Russo, "You know the study I told you about a couple of weeks ago? I've got it at Rand, in my safe, and I'm going to put it out." Russo replied, "Great! Let's do it."

The next evening, before he left his Santa Monica office, Ellsberg slipped a couple of thick volumes of the Pentagon Papers into his briefcase. He chose the volumes on 1964 to 1965. Those volumes could make the strongest case for ending the war. He headed out through Rand's lobby. He waved at the two security guards. They said, “Good night, Dan,” and waved him by. He walked past a World War Two security poster that said, “Loose Lips Sink Ships,” and went out the door.

Ellsberg took the volumes over to Russo's apartment. From there, they went to the offices of an advertising agency run by Russo’s girlfriend, Lnda Sinay. Using a Xerox machine in the agency, Ellsberg and Russo began the time-consuming process of photocopying the Pentagon Papers. Each page of the document took several seconds to copy. They didn't leave the office until 5:30 the next morning.

Ellsberg had a big breakfast, then returned to Rand to replace the volumes in his safe. He drove up to a beach near Malibu, bodysurfed, and went to bed.

The next night, and for many nights thereafter, the copying continued. Ellsberg knew that what he was doing was a crime. He fully expected the day would come when he would pay the price for his actions. He imagined the day his children would come to a prison somewhere and "see me brought into the visitors' booth in handcuffs, wearing prisoner's clothes."

In early November, Ellsberg carried the Pentagon Papers to Capitol Hill, where he met with anti-war congressman to discuss strategies to end U.S. involvement in Vietnam. Ellsberg told Senator William Fulbright, chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee and a Vietnam policy critic, that he had a copy of a secret study that might change public opinion about the war. At Fulbright's suggestion, Ellsberg left a copy of the Pentagon Papers with Fulbright's legislative aide, Norvil Jones.

The next year Ellsberg stepped up his anti-war activities. He resigned from Rand, testified about Vietnam policy before Fulbright's Senate committee, spoke at an anti-war "teach in" at Washington University in St. Louis, and argued for an immediate withdrawal on the national television program The Advocates. In late August 1970, Ellsberg traveled to Kissinger's San Clemente office, where he urged Kissinger to read the Pentagon Papers and to reconsider the Administration's Indochina policy. Ellsberg left his meeting with Kissinger depressed, believing that the lessons of history would not be learned and there was little prospect for a substantial withdrawal of U. S. troops. Working within the administration, it appeared, was an exercise in futility.

By the end of 1970, Ellsberg was giving serious thought to turning a copy of the Pentagon Papers over to the New York Times. First, however, he attempted to find an anti-war senator who might release the study. Ellsberg met with George McGovern, an announced candidate for the Democratic presidential nomination. McGovern responded enthusiastically to Ellsberg's suggestion, but later--when the political implications for his candidacy of releasing a classified study became clearer--he decided he just couldn't do it. If the public where ever to find out the secret history of U. S. involvement in Indochina, Ellsberg would have to go to the press.

On March 2, 1971, Ellsberg traveled to the Washington, D. C. home of New York Times reporter Neil Sheehan and discussed with him the possibility of turning over to the paper a copy of the Pentagon Papers. Ten days later, the two men met again in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Ellsberg sought to get Sheehan to commit to publishing large sections of the study, and Sheehan said he would push his editors to do just that. After Sheehan returned to New York, copy of the Pentagon Papers in hand, he and other reporters at the Times spent the next several weeks sifting through the thousands of pages of the report, looking for reports and anecdotes that would tell a compelling story of how we got into the mess that had become the Vietnam War.

The Nixon Administration Goes to Court to Stop Publication

On Sunday June 13, 1971, the New York Times ran a three-column, front-page story containing excerpts from the Pentagon Papers. At the White House, Richard Nixon read the story with a mixture of disgust and relief. although he told aide H. R. Haldeman that it was "criminally traitorous" for someone to have turned over the Papers and for the Times to then publish them, he was relieved to find that the Papers focused on the earlier missteps of earlier administrations, not his. His first reaction was to "keep out of it" and let the story run its course, but later in the day a riled Henry Kissinger urged Nixon to take steps to stop publication of further stories based on the Pentagon Papers. In Kissinger's view, the release of information threatened ongoing secret negotiations.

As soon as he learned of the Times impending publication of the Pentagon Papers stories, Ellsberg bundled a few things from his apartment and went underground.

On June 15, as the Times published its third installment in the series, the Department of Justice filed a demand for an injunction against further publication in federal district court in New York City. After listening to arguments from lawyers for both the Times and the government, Judge Murray Gurfein granted a temporary restraining order against the Times and then scheduled another hearing for June 17.

Over the next couple of weeks, as the FBI searched for him, Ellsberg would move from one Massachusetts hotel to another, using pay phones for all his communications. He used payphones for all his communications, including calls he placed to Ben Bagdikian of the Washington Post. With further publication at least temporarily blocked in New York, Ellsberg contacted Bagdikian and arranged to deliver an additional copy of the Pentagon Papers to the Post.

Which, of course, created a dilemma for Bagdikian and his colleagues: To publish or not to publish—that was the question. The Post was not legally bound by the restraining order that applied to the Times. But publishing in the face of that injunction posed risks. There was even the possibility that information published by the Post might result in a criminal prosecution under the Espionage Act. And the Post faced business risks that could jeopardize the company’s stock. Moreover, how could the Post guarantee that nothing they published would jeopardize the lives of intelligence agents?

The Post’s lawyers argued for caution. Wait, they suggested. See what happens with the Times case. But reporters and Editor Ben Bradlee wanted to push ahead. It was a huge story. This is when great newspapers step up. The public has a right to know. After a heated discussion between reporters, editors, and lawyers at the Post, the question of whether to publish in the face of the New York court's injunction was presented to publisher Katherine Graham. Fully aware of the potentially serious legal and financial implications of publishing, Graham nonetheless tells editors, "Okay, go ahead."

Over the next several days, in courthouses in both New York and Washington, lawyers debated whether the First Amendment permitted the government to enjoin publication of stories based on the Pentagon Papers. Lawyers for the papers stressed that "prior restraints," such as injunctions of this sort, were "presumptively unconstitutional" and that the government "had a heavy burden of justification" which in these cases had not been met. Justice Department lawyers, on the other hand, argued that information contained in the classified documents might jeopardize sensitive relationships with foreign governments and put the lives of military personnel and other government agents at risk. By June 23, the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals had voted 7 to 2 to deny an injunction against publication in the Washington Post, while the Second Circuit Court of Appeals had remanded the question of injunctive relief against the New York Times to the district judge for further in camera proceedings. It was obvious to all observers that the issue was headed for a showdown in the United States Supreme Court. On June 26, one day after granting review in the Pentagon Papers cases, the nine justices of the Supreme Court heard oral arguments.

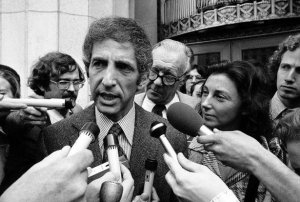

Daniel Ellsberg surrendered to arrest at the federal courthouse in Boston on June 28, even as a federal grand jury in Los Angeles was indicting him on charges of theft and espionage relating to his role in the Pentagon Papers controversy. In Washington, meanwhile, E. Howard Hunt prepared a memorandum (with the heading "The Neutralization of Ellsberg") for Nixon aide Chuck Colson in which he proposed building a file of damning information about Ellsberg that might destroy his credibility. Among Hunt's several suggestions was, "Obtain Ellsberg's files from his psychiatric analysis."

On June 30, the Supreme Court announced a per curium decision in New York Times v United States holding that the government had not met its heavy burden of showing a need for an injunction against publication of stories based on the Pentagon Papers. Separate opinions filed by various justices revealed a deep split. Justices Black and Douglas attacked the government's arguments with vengeance, writing that an injunction "would wipe out the First Amendment and destroy the fundamental liberty and security of the very people the Government hopes to make secure." Justices White and Stewart, concurring, staked out a more moderate ground, suggesting that publication was not in the national interest, but then concluded that they "cannot say that disclosure...will surely result in direct, immediate, and irreparable damage to our Nation or its people." In dissent, Chief Justice Burger and Justices Blackmun and Harlan complained about the haste with which the case was decided. The three dissenters also argued that sensitive and complex foreign policy decisions of the sort raised in the Pentagon Papers case "should be undertaken only by those directly responsible to the people whose welfare they advance or imperil," not judges.

The Ellsberg Trial

In a recorded June 29 conversation with Attorney General John Mitchell, Richard Nixon expressed his determination to see Ellsberg brought to justice. Nixon told Mitchell, "The main ball is Ellsberg. We've gotta get this son of a bitch....One of our . . . PR types [was] saying, 'Well, maybe we ought to drop the case if the Supreme Court doesn't, uh, sustain and so forth.' And I said, 'Hell, no!' I mean you can't do that....We can't be in a position of...allowing the fellow to get away with this kind of wholesale thievery, or otherwise it's going to happen all over the government.'"

Despite strong evidence that Ellsberg copied classified government documents and gave them to the press, the government's case against him was not without problems. Federal espionage laws targeted most clearly those who provided foreign governments with classified information, not those who gave documents to members of Congress or the American press. Even the theft charge raised issues, as the defense would argue that Ellsberg--unlike the vast majority of "thieves"--sought no personal advantage, or advantage for any third party, from copying documents. The defense could also raise issues about whether an historical record, such as the Pentagon Papers, could properly be classified "top secret." Still, as defense attorney Leonard Boudin told Ellsberg, "Let's face it, Dan. Copying seven thousand pages of top secret documents and giving them to the New York Times has a bad ring to it."

In August 1971, when Anthony Russo was called to testify before the grand jury in Los Angeles about his knowledge of the copying of the Pentagon Papers, he refused to testify, citing his Fifth Amendment privilege against self-incrimination. Even after Justice Department officials promised Russo immunity from prosecution (thus, under precedent, eliminating his Fifth Amendment privilege claim), he still refused to talk. On August 16, Russo was sentenced to jail for contempt of court. He remained there for six weeks. After Russo's refusal to testify, a new indictment was drafted against both Ellsberg and Russo. On December 29, the indictment was returned against both men, including fifteen counts relating to theft of government documents and espionage. If convicted on all counts, Ellsberg faced the prospect of a 105-year prison sentence.

The first trial of Ellsberg and Russo came to a sudden halt in July 1972 when it was disclosed that the government wiretapped a conversation between one of the defendants and his lawyer or consultants. Although Judge Byrne refused to stop the trial because of the wiretap, Justice William O. Douglas stayed the proceedings until the Supreme Court had a chance to consider the appeal. In November, the U. S. Supreme Court, voting 7 to 2, refused to hear defense arguments arising from the government's wiretap. Nonetheless, in view of the lengthy break in the trial, Judge Byrne declared a mistrial and ordered a new jury empaneled.

Opening arguments in the second trial of Ellsberg and Russo took place on January 17, 1973 in the federal courthouse in Los Angeles. After prosecutor David Nissen summarized what the government's evidence against the two men would show, defense attorney Leonard Boudin delivered his opening statement. Boudin suggested that the Pentagon Papers "belong to the people of the United States." Because of this public ownership, Boudin told jurors, copying them and giving them to the press, so that the American people could be told their contents, should not be considered theft. "You will come to the conclusion...that the revelation of this information to your senators and congressmen was helpful to the interests of the United States," Boudin said.

The government's witnesses testified that the Pentagon Papers were indeed classified "Top Secret," that Daniel Ellsberg had signed a security statement with Rand promising not to transmit "classified information to an unauthorized person or agency," and that neither Anthony Russo or Linda Sinay had any security clearances. Linda Sinay Resnick, an unindicted co-conspirator, told jurors that she observed Ellsberg and Russo copying the secret papers on the Xerox machine in her ad agency office. The final witness for the prosecution, FBI agent Deemer Hippensteel, testified that he found the fingerprints of Ellsberg, Russo, and Sinay on volumes of the Pentagon Papers submitted into evidence. None of the government's evidence surprised anyone who had been closely following the case.

Morton Halperin, the supervisor of the Pentagon Papers task force, testified for the defense. Halperin testified about the decision to store a copy of the Pentagon Papers "outside the normal Rand top secret control system," by simply placing them in a separate top secret safe. Halperin told jurors that he approved a request from Ellsberg that he be given access to the volumes for continuing work at Rand's Santa Monica office on Vietnam policy.

Anthony Russo, on the stand, admitted the obvious: in the fall of 1969, he had helped photocopy the Pentagon Papers at the Hollywood office of his then girlfriend, Linda Sinay. He testified that he did not handle or even see those documents again until arriving in the Los Angeles courtroom. Questioned about his years in Vietnam, Russo told of interviewing Vietnamese in connection with a Rand assignment to prepare a report on the effectiveness of anti-personnel weapons. Russo said he learned of many cases in which "young children would pick up" the shiny, unexploded weapons and take them home, "and then it would go off and kill the whole family." He testified that his interviews with Vietnamese prompted a realization that the Viet Cong were not "indoctrinated fanatics," but rather people with "a real commitment" to their cause. Russo said he decided to leave the study when he found that his reports from Viet Nam "were being altered...to promote the role of the Air Force," Rand's client. Russo testified about a beach-front conversation with Ellsberg in September 1969. Both men agreed that they had witnessed "a very definite pattern of lying and deception" from U. S. officials concerning Viet Nam policy. On October 1, 1969, Russo testified, Ellsberg visited his home and asked whether he would be willing to help copy the Pentagon Papers study. During cross-examination, in an answer that was objected to and stricken, Russo claimed "any American who cared about his country...would consider it his official duty to get these documents...to the American people." He admitted, however, that he knew he lacked security clearance to see the documents.

When Daniel Ellsberg took the stand, Boudin questioned him about his experiences in Viet Nam. Ellsberg testified he saw "a very great divergence" between what he learned "along the roads and hamlets of Viet Nam" and what military advisers were telling their bosses. He explained his role on the Pentagon Papers task force and his later interest in securing access to the finished study. He testified, "I knew that not a page of [the Pentagon Papers] could injure the national defense if disclosed to anyone, and had I believed otherwise I would not have copied it." Ellsberg said he passed on the Papers in the hope that the revelations contained in them "might give Congress the self-confidence to act to end the war." On cross-examination, Ellsberg conceded that he "had no permission from anyone to remove the documents from the Rand premises."

On April 27, 1973, Judge Byrne turned over to the defense a shocking memo from Watergate prosecutor Earl Silbert to Assistant Attorney General Henry Peterson. The memo said that Silbert had just learned that "Gordon Liddy and Howard Hunt burglarized the offices of a psychiatrist of Daniel Ellsberg to obtain the psychiatrist's files relating to Ellsberg." After news of the memo reached the press, new facts began emerging, including the names of three Cuban-American Bay of Pigs veterans who committed the actual break-in at Dr. Lewis Fielding's office. (Two of them, Bernhard Barker and Eugenio Martinez, had been arrested inside the Watergate offices of the Democratic National Committee in June, 1972.) The burglary was approved by none other than the president himself, according to Nixon aide John Ehrlichman. Though that fact was unknown at the time.

(Believe it or not, crazier plans than raiding Ellsberg's psychiatrist's office were hatched, but not carried out. The craziest of all was a plan to steal possible evidence about Ellsberg from a security vault at the Brookings Institution. Liddy suggested buying a fire engine and marking it to look like a Washington DC fire engine. A conspirator would set off a firebomb at the Brookings at night. Then a bogus fire engine would pull up and Cubans dressed like firemen would get off and rush into the building. They’d hit the vault and “rescue” the sensitive material about Ellsberg before anyone could figure out what was happening.)

Judge Byrne demanded that the government reveal whether "Hunt and Liddy were acting as agents of the government at the time of burglary, and at whose direction." When it became clear that the break-in was committed by employees of the White House pursuing a project launched by the President, the basis for a mistrial grew compelling. And in Washington, heads began to roll. On April 30, Nixon announced the departures of John Erlichman, H. R. Haldeman, Richard Kleindeist, and John Dean.

On May 11, Judge Bryne ruled on the defense motion for a dismissal of all charges against the defendants based on the government's gross misconduct. Byrne granted the motion, writing that "the bizarre events have incurably infected the prosecution of this case." When the judge finished his statement, the courtroom erupted in roars and laughter. Ellsberg and Russo would never see the inside of a jail.

Meanwhile, in Washington, Richard Nixon complained to his former chief of staff H. R. Haldeman: "The sonofbitching thief is made a national hero...The New York Times gets a Pulitzer Prize for stealing documents...They're trying to get us with thieves. What in the name of God have we come to?" Nixon’s head speech writer would later describe his boss’s mood as “ferocious.”

Well, what had we come to? White House lawyer Bud Krogh described the Pentagon Papers as “probably the seminal event” that caused the downfall of Nixon. Haldeman said the President “lost his head” during the incident.

The Pentagon Papers cases resulted in a strong decision affirming the right of a free press to publish even information the government claimed threatened national security. By any measure, a victory for the Press.

The cases should not, however, be read as giving a greenlight to citizens to steal and expose secret documents. Stealing government secrets cannot be any part of ordered liberty. Ellsberg was not vindicated; Ellsberg was the beneficiary of the inexcusable actions of an Administration increasingly untethered from the rule of law. An Administration that believed that the ends almost always justified the means.