by Douglas O. Linder (2023)

When, on December 1, 1955, Rosa Parks refused to obey an order to give up her seat on a Montgomery bus to a white person, an action that led to a boycott of the Montgomery bus system, she had in mind a murder trial that happened two months earlier in Sumner, Mississippi. A fourteen-year-old boy, Emmett Till, had been brutally murdered and his body thrown in the Tallahatchie River, but despite clear evidence that two white men committed the crime, an all-white jury returned a "Not Guilty" verdict after just an hour of deliberation. Parks wrote, "the news of Emmett's death caused me...to participate in the cry for justice and equal rights." Parks, in an interview, described herself as "very upset, very devastated [that] a child could be just taken out and killed." The trial of Roy Bryant and J. W. Milam for the murder of Till shook the conscience of a nation and helped spark the movement for civil rights for black Americans.

Background

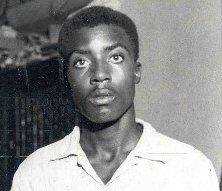

On July 25, 1941, Mississippi-born Mamie Till gave birth to a son, Emmett Louis, at Cook County Public Hospital in Chicago. Mamie raised Emmett (or "Bobo," as he was called by family and friends alike) largely without help from her mostly absent, and soon-to-be-dead husband, Louis Till, who was executed by the U. S. Army in July 1945 for the rape of two women and the murder of another in Italy. Nonetheless, Mamie described her life with young Bo at her mother's house in downtown Chicago as being "as close to perfect as you could get." Despite suffering through a bout with polio at an early age that left him with a stutter, Emmett enjoyed many friends and, in the words of his mother, "was always into something." His mother pegged him to become "a good lawyer or politician."

On August 20, 1955, Mamie put her fourteen-year-old son on a southbound train in Chicago's Central Station for a planned two-week stay with relatives near the small northern Mississippi town of Money. Emmett sampled the Mississippi life of his cousins during the first three days of his visit: picking cotton, shooting off fireworks, stealing watermelons, and swimming in a snake-infested pond.

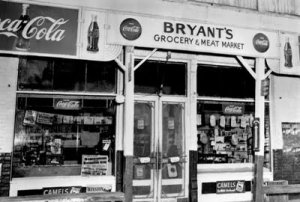

On the evening of the 24th, Emmett, and five of his relatives and their friends, drove a few miles to Bryant's Grocery & Meat Market in Money. After a few minutes of milling around in front of the store, Emmett followed one of the other boys into the Bryant store. After the other boy made his purchase, Emmett was left alone in the store for a minute or so with Carolyn Bryant, the white woman working the store's cash register. What was done or said in those few moments is not known for certain, but whatever happened doomed Emmett.

As Carolyn Bryant would later tell the story in a Tallahatchie County courthouse, Till asked her for some candy inside a candy counter. When Bryant placed the candy on top of the counter, Till grabbed her right hand tightly and asked, "How about a date, baby?" When Bryant pulled her hand free and started to walk away, Till grabbed her by the waist near the cash register and told her, "You needn’t be afraid of me, baby I’ve [slept] with white women before.” Till's cousin, Simeon Wright, writing about the incident decades later, questioned Carolyn Bryant's account. Entering the store "less than a minute" after Till was left inside alone with Bryant, Wright saw no inappropriate behavior and heard "no lecherous conversation." Wright said Till "paid for his items and we left the store together."

There is, however, general agreement about what happened next outside the store. As Carolyn Bryant left the store and headed towards a car (to retrieve, she testified, a gun), Emmett whistled at her. Till's cousin described it as "a loud wolf whistle, a big city 'whee wheeeee!'" Till's Mississippi cousins instantly knew that Till had broken a longstanding taboo relating to social conduct between blacks and whites, and that they were in grave danger. They quickly ran to their car and sped out of Money.

(Carolyn Bryant claimed later, in an unpublished memoir leaked in 2022, "I Am More than a Wolf Whistle", that Till grabbed her hand and her waist before whistling at her, but that claim is disputed by Till's relatives. Bryant also claimed that she screamed in response to Till's touching and his whistle.)

The town was rife with talk about the incident at Bryant's store. On Friday August 26, Carolyn's husband Roy returned from Texas, where he had been hauling shrimp.

Two days later, Carolyn’s husband, Roy, returned from Texas, where he had been hauling shrimp. Carolyn, possibly fearing what her husband might do, told him nothing about what had transpired in the store. But later that day, someone at the store, most likely a local black fieldhand hoping to “curry favor,” as a New York Times story put it, told Roy Bryant about the incident. He also identified a visiting teenager from Chicago as the offender. To do nothing after hearing the story involving his wife, Bryant later told an interviewer, would have shown himself to be "a coward and a fool." Returning home, Roy asked Carolyn if there was something she wanted to tell him. Her denial angered Roy, and he demanded to hear his wife's version of what had happened inside the store. She told him the version of events she would later repeat in his trial.

Sometime on Saturday August 27, plans fell into place to kidnap the offending black teenager and "teach him a lesson." Bryant's half-brother, John W. Milam, readily agreed to help. The two men operated businesses together, played cards together, drank together, and were described in the FBI's investigation as being "particularly close." According to historian Hugh Whitaker, who interviewed dozens of Mississippians who knew Bryant and Milam, the two "were invariably referred to as 'peckerwoods,' 'white trash,' and other terms of disappropriation."

On the evening of the 27th, Bryant and Milam, along with Carolyn Bryant and Johnny Washington (a black man who performed odd jobs for Bryant) set off in a pickup looking for their target. Spotting a black teenager walking home with some molasses and snuff, Bryant ordered Washington to throw the boy in the back of the truck, and Washington did so. When Carolyn emerged from the truck to tell Bryant, "That's not the nigger! That's not the one!", Bryant ordered Washington to throw him out the truck. The teenager landed head first, losing his front teeth.

Within the next few hours, Bryant and Milam somehow learned that the wolf-whistler was staying at the home of "Preacher" Moses Wright. At 2:30 a.m., a vehicle with headlights off pulled up in front of Wright's home east of Money. Till and his relations had arrived home after a night of drinking and looking for girls in Greenwood, Mississippi, but were asleep when a voice called out, "Preacher, Preacher!" When Wright went to the door, the man identified himself as Roy Bryant and said that he wanted to talk to "a fat boy" from Chicago. Standing on the porch with Bryant were Milam and a black man, hiding his face, who (according to his own later admission) was Otha Johnson, Milam's odd-job man. The men searched the occupied beds looking for Till. Coming to Till's bed, Milam shined a flashlight in the boy's face and asked, "You the niggah that did the talking down at Money?" When Till answered, "Yeah," Milam said, "Don't say 'yeah' to me, niggah. I'll blow your head off. Get your clothes on." As Emmett's cousin would later tell the story, when Moses Wright pleaded with the two men not to take Emmett, Bryant appeared to hesitate, but Milam insisted on going ahead with the planned abduction. Warning the Wrights they'd be killed if they told anyone they had come by, Milam and Bryant ushered Till out of the house and to their parked vehicle. Standing on the porch looking out into the dark, Moses Wright heard a woman's voice--possibly Carolyn Bryant's--from inside the vehicle tell the abductors they had found the right boy.

What happened over the next three or four hours is not known for certain. It is generally agreed that Bryant and Milam brought Till to Carolyn Bryant for identification shortly after abducting him. In her unpublished 99-page memoir, Bryant claimed that she told her husband and Milam that Till was not the boy who whistled at her and urged them to let him go. (Till's relatives argued that Carolyn's story is implausible in light of subsequent events and is merely a self-serving lie.)

After seeing Carolyn, according to Bryant's and Milam's own account, given in an interview following their acquittal, they initially intended to "just whip him...and scare some sense into him." Milam claimed they drove Till seventy-five miles to the west, searching for a cliff they'd visited before with a sheer hundred-foot drop down to the Mississippi River. Failing in the darkness to find their bluff, the men drove back to a barn on the farm of Leslie Milam (J.W.'s brother) near Drew, Mississippi.

Willie Reed, who later would testify for the prosecution, saw at about 6:00 a.m. a white and green Chevrolet truck, with four white men riding in the cab and three black men standing in the back of the truck. Reed saw an eighth person, a black boy (presumably Till), seated in the bed of the truck. The truck, according to Reed, parked in front of the barn. Minutes later, he said, he heard "hollering" and what sounded like "whipping" coming from the barn. (In later interviews, Reed identified four men he saw entering the barn: Bryant and Milam, as well as two black men, including Levi "Too Tight" Collins (a truck driver for Milam).

Despite a different version of events offered by Bryant and Milam in their 1956 interview, Till was most likely shot and killed in Leslie Milam's barn. (Milam claimed to have shot Till on the banks of the Tallahatchie, but that was a fiction to protect Leslie Milam, who still faced possible prosecution.) Milam and Bryant described Till as defiant, even during his pistol-whipping in the barn. According to the two men, Till said, "You bastards, I'm not afraid of you. I'm as good as you are. I've had white women." Milam said, "When a nigger gets close to mentioning sex with a white woman, he's tired of living. I'm likely to kill him...I stood there in that shed and listened to that nigger throw that poison at me, and I just made up my mind." After the pickup left the farm, it stopped briefly at J. W. Milam's store in Glendora. There, a witness noticed "blood running out of the bed of the truck and pooling on the ground." When the dripping blood was pointed out to Milam, when he returned to his truck, J. W. claimed that he killed a deer. When Milam was told it was not deer season, he allegedly pulled back the tarpaulin in the bed to reveal Till's body and said, "This is what happens to smart niggers." [FBI report, p. 64] Milam, Bryant, and the others (including "Too Tight" Collins and Otha Johnson) loaded themselves back into the truck and left town.

Bryant and Milam decided to throw Till's body into the Tallahatchie River. Before doing so, they stopped at a ginning company to steal a heavy fan that they planned to use to weight down the corpse. They drove north toward Swan Lake, crossed the bridge over the Tallahatchie, and stopped on a dirt road, near a steep bank in the river. The men tied the fan to Till's neck with barbed wire and rolled the dead fourteen-year-old into the river. In the time between the abduction and the disposal of the body, the killers had travelled between 60 and 150 miles over three counties.

Three days later and eight miles downstream, a boy named Robert Hodges, who was fishing in the Tallahatchie, saw feet sticking out of the water. The badly beaten and bloated body was pulled from the river and loaded into a boat. Hodges and others observed a silver ring on one of the body's fingers. Called to the scene, Mose Wright looked into the boat on the riverbank and identified the body of Emmett Till. A black undertaker and his assistant lifted Till's body from the boat and placed it in a casket. The undertaker's assistant gave the ring to Wright, who later turned it over to LeFlore County Deputy Sheriff John Ed Cothran.

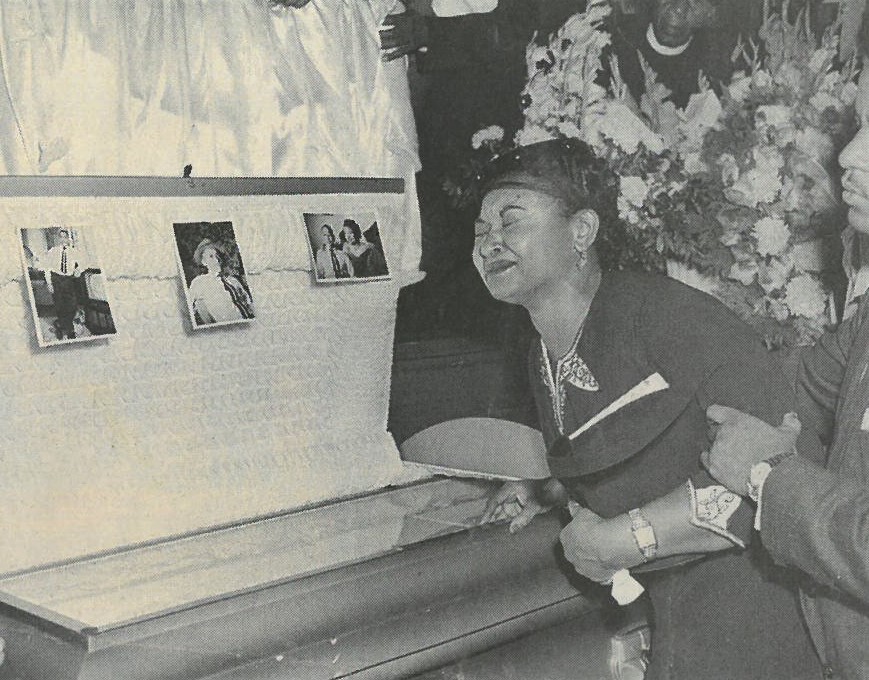

Later, at the Illinois Central Station in Chicago, a large crowd watched five men lift a paper-wrapped bundle containing the body of Till and place it in a waiting hearse. As they did so, Mamie Bradley wailed, "Oh, God. Oh, God. My only boy." Bradley insisted that her boy be displayed in an open casket so that viewers could see the gruesome damage inflicted by the murderers. Approximately 50,000 persons filed by Till's casket in the funeral chapel at 4141 Cottage Grove. Bradley told reporters, "Unless an example is made of the lynchers of Emmett, it won't be safe for a Negro to walk the streets anywhere in America." Bradley said she was determined to see her son's killers executed. Chicago's Mayor Richard Daley joined the fight for justice, wiring President Eisenhower with a call for federal action against the lynchers.

The Trial

Within a day after Till's disappearance, both Roy Bryant and J. W. Milam had been arrested for his abduction. Both men admitted to taking Till from Wright's home, but insisted that they let him go in Money.

On September 3, two days before a grand jury in Tallahatchie County would indict Bryant and Milam on both murder and kidnapping charges, the County's sheriff, H. C. Strider, made the surprising statement that he doubted the body pulled from the Tallahatchie River was that of Emmett Till. Strider told reporters "the body looked more like that of a grown man instead of a young boy" and had probably been in the river "four or five days"--too long to have been the body of Till, abducted just three days earlier. Strider expressed his opinion that Till "is still alive." The theory for a murder defense, with the now obvious support of the County's sheriff, had been laid.

In the first few days following the discovery of Till's body, there was reason to hope that justice might follow. Mississippi Governor Hugh White telegrammed District Attorney Gerald Chatham "urging vigorous prosecution of the case." For his part, Chatham said, "Murder is murder whether it is black or white, and we are handling this case like all parties are white." Mississippi citizens expressed shock over the crime. Ben Roy, a white merchant in Money, told reporters, "Nobody here, Negro or white, approves of things like that." Local newspapers added their condemnation. The Greenwood Commonwealth editorialized, "The citizens of this area are determined that the guilty parties shall be punished to the full extent of the law."

Then everything changed. When Roy Wilkins, Executive Secretary of the NAACP, described Till's killing as a "lynching" and opined that "the state of Mississippi has decided to maintain white supremacy by murdering children," many Mississippians were deeply offended and angered. According to historian Hugh Whitaker, the strident remarks of Wilkins and other northern opponents of segregation caused the local power structure to dig in, and throw its support to Bryant and Milam, two men they otherwise might have been happy to see put away. All five lawyers in the town of Sumner, where the Bryant-Milam trial would be held, agreed to serve as defense counsel. One of the defense lawyers acknowledged later that he only agreed to represent Bryant and Milam after "Mississippi began to be run down."

Many Mississippi citizens expressed shock over the crime. Local newspapers added their condemnation. The Greenwood Commonwealth editorialized, "The citizens of this area are determined that the guilty parties shall be punished to the full extent of the law."

Add to this, the prosecution also knew that Bryant and Milam were not popular among local residents. The two men operated businesses together, played cards together, drank together. Drank a lot. According to historian Hugh Whitaker, who interviewed dozens of Mississippians who knew Bryant and Milam, the two "were invariably referred to as 'peckerwoods' or 'white trash.'” A conviction seemed possible. Maybe even likely.

The Role of Sectional Differences

Then everything changed. Roy Wilkins, Executive Secretary of the NAACP, described Till's killing as a "lynching" and opined that "the state of Mississippi has decided to maintain white supremacy by murdering children." Many Mississippians took offense. The local power structure dug in and threw its support to Bryant and Milam, two men they otherwise might have been happy to see put away. All five lawyers in the town where the Bryant-Milam trial would be held agreed to serve as defense counsel. One of them said he decided to do so only after "Mississippi began to be run down" in the national press.

Not every trial is decided based on the evidence. In fact, in some trials, the evidence may hardly matter at all. And the Emmett Till trial might be a perfect example. To understand this trial, you have to understand attitudes of people in the Deep South in the 1950s. For the first time, their policy of segregation was coming under serious attack. Most white southerners adopted an “Us against the World” view. Attitudes hardened enough that jurors might well have thought it more important to send a message to liberals and northerners than to achieve justice in a murder trial.

And there is a second way in which sectional differences played a role in this case. Emmett Till (“Bobo” to his friends) had the style and attitudes of a northern African-American teen. The taboos of Mississippi didn’t exist in Chicago. Emmett, for example, shocked his southern cousins with his “Yeah” and “Nah” replies to local whites. Not the “Yes, sir” or “No, Mam” that Southern blacks were taught to use. But what most fascinated Emmett’s black cousins was the picture of the white girl he carried in his billfold. Bobo told them it was a picture of “his girl” back in Chicago. A relationship, that to his cousins, must have seemed almost unimaginable. Before the fatal drive to the store in Money, one of Emmett’s friends or relatives reportedly said to him: “You talkin’ mighty big, Bo. There’s a pretty little white woman in there in the store. Since you Chicago cats know so much about white girls, let’s see you go in there and get a date with her.” Emmett might have feared losing face. He might have felt he had to ask Carolyn Bryant, a two-time high school beauty pageant winner, for a date.

There is another thing young African-Americans in the Deep South knew not to do, but a young northerner like Emmett would not. When paying for an item, the custom for southern blacks was to put the coins on the counter, not in the hand of a white clerk. Black skin touching white skin was a taboo. It’s possible—some commentators have theorized—that Emmett’s trouble began by putting a few pennies into Carolyn Bryant’s hand. But, then again, Carolyn Bryant has stood by her story of wrist-grabbing. Stood by it even as she expressed deep regret for what happened to Emmett.

Or perhaps Emmett died because when J. W. Milam flashed a light into his face that night at the home of Moses Wright and asked him whether he was the boy who talked to Mrs. Bryant, he answered “Yeah”—not “Yes, sir, I am.” Emmett’s “Yeah” clearly set Milam off, causing him to yell at Emmett.

Or maybe Milam and Bryant just couldn’t stand Emmett’s northern belief in his own equality. Even while being pistol-whipped in a barn after his abduction, Emmett remained brash and defiant, according to a story written some time later by his murderers. They reported Emmett told them, “You bastards, I’m not afraid of you. I’m as good as you are. I’ve had white women.” In Milam’s words, “When a (n-word) gets close to mentioning sex with a white woman, he’s tired of living.” It was then, Milam said, “I just made up my mind to kill him.” Milam shot Emmett in the head with a .45 revolver. So by these accounts, Emmett Till died because Bryant and Milam refused to tolerate his Chicago ways—a pitiful attempt to excuse a murder.

Jury selection began on September 19, three weeks after Emmett's body was recovered. Finding twelve unbiased jurors would not be an easy task. One prospective juror, Robert Smith, neatly described the problem when asked whether he had a "fixed opinion" in the case. Smith answered, "Anybody in his right mind would have a fixed opinion." In 1955, none of the black residents of Tallahatchie County were registered voters and thus, under the jury selection rules then in place, no black was eligible to serve as a juror. During the six hours of jury selection, the county's sheriff-elect assisted the defense team, advising the lawyers as to which jurors were "doubtful" and which were "safe." All of the twelve white men seated for the jury seemed safe. One of the defense attorneys said later, "After the jury was chosen, any first-year law student could have won the case."

More than seventy reporters, photographers, and radio and television broadcasters, some from as far away as London, packed the small courtroom in an old brick courthouse in Sumner, Mississippi. Most of the more than a thousand “outsiders” that flocked to the site of the trial had to content themselves with hanging around the courthouse lawn. The courtroom itself was segregated, with whites occupying most of the hundred or so seats and blacks confined to the back of the room. Bryant and Milam, at the defense table, seemed to be enjoying themselves, laughing and joking with relatives and supporters.

Moses Wright was the state's first witness. Wright testified that Milam and Bryant came to his home on August 28 and carried his young relative off into the night. Asked to identify the two men, Wright rose dramatically from the stand at pointed his finger directly at the defendants. Wright also told jurors he identified the body pulled from the river as being Emmett Till and that he was "looking right at" the undertaker as he pulled the ring with the inscription "L.T." from one of Till's fingers. He also identified the silver ring in the courtroom, one of the prosecution's key exhibits, as being the ring he saw removed from Till's body.

Anticipating the defense's theory that the body removed from the Tallahatchie was not that of Till, the state called to the stand an undertaker, a police identification officer, and finally Till's mother, Mamie Bradley, to--it hoped--eliminate all reasonable doubt on the question. Bradley testified, "I positively identified the body in the casket, and later on when it was on the slab, as being that of my son, Emmett Louis Till." She also identified the ring as being the ring returned to her from Europe with her husband's other effects after he was killed.

A series of prosecution witnesses left no reasonable doubt that Milam and Bryant abducted Till, and very little doubt that they killed him hours later. Deputy Sheriff John Ed Cothran testified that after his arrest J. W. Milam freely admitted kidnapping Till from Wright's home. Then three surprise witnesses placed the defendants at Leslie Milam's barn in the early morning of August 28. Most compelling was the testimony of Willie Reed, who said that after he witnessed Milam, Bryant, and several other men park a pickup on Milam's property, he heard "licks and hollering" from within the barn. (Two potential key witnesses, both blacks who allegedly assisted with the abduction and murder of Till, were unavailable to the prosecution. Both Leroy "Too Tight" Collins and Henry Loggins, who prosecutors assumed only to be missing, were actually being held under false identities in a jail in Charleston, Mississippi under orders of Sheriff Strider, who had thrown the full weight of his office behind the defense efforts.) Reed said he was later confronted by Milam, who asked him if he had heard or seen anything. Reed told him “No.” Reed also testified that some time earlier he was passed by a green and white pick up truck. He said four white men rode in the cab, with three black men in the truck bed, one sitting down in back watched over by the other two. The seated young black man, Read said, resembled Emmett Till.

On Thursday afternoon, the state rested and the defense presented its first witness, Carolyn Bryant. Testifying with the jury excused, Carolyn Bryant described the August 24 incident at Bryant's Grocery & Meat Market. Bryant said that "just after dark" with her alone in the store, Till strongly gripped her hand as she held in out on the candy counter to collect money. She said she jerked her hand loose "with much difficulty" as Till asked her, "How about a date, baby?" When she tried to walk away, she stated, Till grabbed her by the waist and said, "You needn't be afraid of me. I've"--and here Bryant said Till used an unprintable word for sexual intercourse--"white women before." Bryant testified, "I was just scared to death."

After listening to Bryant's testimony, Judge Curtis Swango ruled it inadmissible though, as courtroom observers noted, every juror undoubtedly had heard Bryant's story already anyway. Judge Swango said that whatever might have happened in the grocery store provided no justification, as a matter of law, for an abduction and murder four days later. But, as courtroom observers noted, every juror undoubtedly had heard Bryant's story already anyway. And they considered it relevant.

A word here about the long-lasting controversy over Carolyn Bryant’s stricken testimony. In his 2017 book The Blood of Emmett Till, author Timothy Tyson claimed that Carolyn admitted in a 2008 interview that part of her testimony was a lie. According to Tyson, she said that Emmett did grab her hand and whistle at her, but that her testimony about Emmett grabbing her waist and uttering a sexual obscenity was an embellishment encouraged by defense attorneys. Tyson quoted Carolyn as telling him, “You tell these stories for so long that they seem true. But that part was not true.” If Tyson’s account is accurate, what does that mean? Can a defense attorney tell a witness to embellish a story—that is, tell a witness to lie? Absolutely not. In fact, in pressing a witness to lie on the stand, an attorney is as equally guilty of perjury as the witness testifying. But would Bryant’s and Milam’s attorneys worry about this as a possible consequence of their action in pushing Carolyn to make her story more dramatic? Of course not. Not in this place, in this time, in this case.

But Tyson’s account of the embellishment, and Carolyn’s alleged recantation, has recently been questioned. A 2021 FBI review found nothing in Tyson’s recording of the interview that backed up the charges made in his book. And in an unpublished memoir by Carolyn, which surfaced in 2022, she stood by her original story. She did say in her memoir, however: “He came in our store and put his hands on me with no provocation. Do I think he should have been killed for that? Absolutely, unequivocally, no.”

The defense’s main argument at trial, if you can call it that, was that the body pulled out of the river was not Emmett Till, and while Bryant and Milam might have abducted Till, they didn’t murder him. Sheriff H. C. Strider testified for the defense. Strider claimed, based on his experience, that the body found in the Tallahatchie River must have been there from "ten to fifteen days." He insisted the corpse was unidentifiable, claiming, "All I could tell, it was a human being."

H. D. Malone, Till's embalmer, added support to the defense theory by testifying the body was so decomposed it had to have been in water for at least ten days and was "bloated beyond recognition." Oddly and interestingly, no autopsy had been performed on the body.

It’s safe to say that no one, not the prosecution witnesses and not the jurors, really believed the body pulled from the river was not that of Emmett Till. But the testimony of Strider, Malone, and a white physician merely provided the jury with the "reasonable doubt" excuse it wanted to acquit Milam and Bryant.

After brief testimony from five character witnesses for Milam and Bryant, closing arguments began. District Attorney Chatham, in a speech that moved many in the courtroom audience, demanded justice for the murder of Till: "They murdered that boy, and to hide that dastardly, cowardly act, they tied barbed wire to his neck and to a heavy gin fan and dumped him into the river for the turtles and the fish. The two defendants, Chatham insisted, "were dripping with the blood of Emmett Till." Chatham called the prosecution’s theory that the body was not that of Till ridiculous: “If there was one ear left, one part of his nose, any part of Emmett Till’s body, then I say to you that Mamie Bradley was God’s given witness to identify him.”

Defense attorneys, for their part, told jurors, "Every last Anglo-Saxon one of you has the courage to set these men free."

When the jurors were sent out to begin deliberations, according to Hugh Whitaker, Sheriff-elect Dogan told jurors to wait a while before coming out, to make "it look good." The jurors enjoyed Cokes before returning 68 minutes later to the courtroom to announce their verdict of "Not Guilty." Cheers went up from most of the white spectators. Bryant and Milam lit up cigars as friends hugged them and slapped them on their backs.

Roy Bryant and J. W. Milam murdered Emmett Till. Everyone in the courtroom, every juror in the jury room, knew that to be a fact. Yet both men were acquitted. The defense gave the jury all they needed to reach their decision: a so-called reasonable doubt about the identity of the body.For all practical purposes, this murder trial was decided the day the jury was seated.

Aftermath

The jury's verdict provoked both angry editorials and calls for federal legislation to protect the civil rights of black Americans. Protest rallies, drawing thousands in some cases, were held in several cities. In the south, the verdict seemed to spell the end to the system of "noblesse oblige," and marked the real beginning of the civil rights movement in that part of the country. In parts of Mississippi, at least, the verdict seemed a declaration of open season on blacks for even small offenses. Two months after the verdict, a white man killed a black gas station attendant at a service station in Glendora after an argument about the amount of gas the attendant put in his car. (The killer, Elmer Kimbell, was acquitted after trial in the same Sumner courtroom where Bryant and Milam heard a jury foreman announce, "Not Guilty.") Within four years after Till murder trial, over 21% of the black population of Tallahatchie County had left.

For Bryant and Milam, the trial in some ways was the beginning, not the end of their troubles. Milam's and Bryant's stores, which catered almost exclusively to local blacks, were boycotted, and within fifteen months after the trial, all the stores were either closed or sold. Blacks refused to work on the Milam farm. J.W. Milam turned instead to bootlegging. Bryant and Milam, not triable again because of the Double Jeopardy Clause, sold their story of the Till abduction and murder in 1956 to Look magazine for $3500. Their decision to profit from the murder offended many of the very people who had helped with their legal defense.

Sheriff Strider came under heavy attack in both national and Mississippi newspapers. Five black families left his delta plantation for work elsewhere. In 1957, Strider narrowly escaped an assassination attempt as he was seated in his car in front of a store in Cowart, Mississippi.

In 1985, five years after Milam died of cancer, some of Roy Bryant's recollections of the Till case were secretly recorded on audiotape. On the tapes, Bryant says of the night of the kidnapping, "Yeah, hell we were drinking." He claimed at one point he and Milam had decided to take Emmett to the hospital. But his injuries were too extensive. So, Bryant said, “We decided to put his ass in the Tallahatchie River." Bryant did not name others involved in the crime and indicated that he never would: "I'm the only one living that knows--and that's all that will ever be known."

Bryant died nine years later, also of cancer, at the age of 63. Carolyn died in 2023, at age 88, regretful according to most accounts, of all that followed from one August day in her little country store.

None of the other men who participated in the kidnapping, beating, or murder of Emmett Till ever faced charges, although the Department of Justice reopened the case in 2004. In 2005, Till's body was exhumed and autopsied by the Cook County coroner. After analysis using dental comparisons, the body was positively identified as Till's. Metallic fragments in the skull suggested he was shot with a .45 caliber gun.

Today, after being memorialized in plays and songs, the 1955 trial of Roy Bryant and J. W. Milam is remembered as a turning point in civil rights history. In the 1962 words of America's greatest singer-songwriter, Bob Dylan:

The jury found them innocent

And the brothers they went free

While Emmett's body floats the foam

Of a Jim Crow southern sea.

If you can't speak out against this kind of thing

A crime that's so unjust

Your eyes are filled with deadman's dirt,

Your mind is filled with dust.

Note on Sites Related to the Till Murder and Trial

Key sites relating to the abduction and killing of Emmett Till can be found in three Mississippi counties: Leflore, Sunflower, and Tallahatchie. Bryant's Grocery store in Money, Mississippi (Leflore County) is now a crumbling ruins, missing its roof and overgrown with vegetation. Preservations hope to acquire the property and restore the store, but the property owner (and son of one of the jurors who voted to acquit Till's killers) has resisted selling at a reasonable price. (He demanded a million dollars for the property.) A service station next to (directly south of) Bryant's, oddly enough, has been restored with a $200,000 grant. But all that can be said of the gas station is that it is a place where locals in the Fifties discussed the Till killing. The service station has nostalgic, but little historic, value. Nothing remains of the Wright home nearby where the abduction took place. No effort has been made to preserve the former barn in Sunflower County where Till's murder actually took place. Most recently, the remodeled structure has been owned by a local dentist. In Tallahatchie County, the courthouse in Sumner where the trial took place has been restored and is well worth visiting. The Emmett Till Interpretive Center in Sumner houses photographs and artifacts relating to the Till case. In the poor and largely African-American town of Glendora, where Till's body was disposed of, 18 signs mark sites relating to the tragic night in 1955. The signs have been repeatedly vandalized and are riddled with bullet holes. A museum relating to the Till case is located in the former gin building from which the fan used to weight down Till's body was likely taken. (DL, 2023).