George Floyd Murder Trial (Trial of Derek Chauvin): An Account

by Douglas O. Linder (2023)

The shocking death of George Floyd on May 20, 2020, following a neck restraint applied by Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin in the presence of three other officers--a scene captured on video and viewed by hundreds of millions of people--set off a wave of violent protests in Minneapolis and around the world. Commentators and a majority of the public saw the excessive use of force by a white officer against a black man as an example of entrenched police racism and the lack of equal justice under the law. While no one should doubt that racism remains a problem in the United States, there was very little evidence in the case to suggest that Chauvin's actions were racially motivated. Also, it is worth noting, none of the three other officers charged in the case, including an African-American, an Asian-American, and a Caucasian, had a history of racial animus. Race and racism hardly warranted a mention in the trial that followed. Defendant Derek Chauvin, at his worst, was an "equal-opportunity" bad cop with a record of using excessive force against both black and white suspects. But facts often matter little in the court of public opinion, where first-take narratives tend to take on a life of their own. Given the public protests and general outcry, the pressure on prosecutors, jurors, and judges to come down heavily on Chauvin was immense, and his resulting stiff sentence (and even his near-murder three years later in a federal prison) should have come as no surprise to close observers of the trial that came to symbolize so much more than it was actually about.

The Death of George Floyd

Darnella Frazier, in sweatshirt and bright blue pants, films the arrest of George Floyd

About 8:00 on the evening of May 25, 2020, Darnella Frazier’s 9-year-old cousin asked her if she would take her to a Cup Foods store near their south Minneapolis apartment. Darella, 17, and her young cousin were a few storefronts down from the grocery store when she saw four officers pull a black motorist roughly from his vehicle. Darnella pulled out her iPhone and began recording. The video Frazier recorded would be replayed tens of thousands of times and spark a movement across America that will forever change race relations in this county. Darnella remained largely silent about her world-changing video for many months. Only when the trial of George Floyd opened ten months later did she began to speak out on social media. She indicated that the video changed her too. She suggested on Facebook that anyone who thought Derek Chauvin (the officer pictured below) was 'just doing his job," is "part of the problem." She added, "I can't go to sleep in silence, my mind will eat me alive."

The video was shocking. It showed Officer Chauvin using his knee to pin a handcuffed 46-year-old African American, George Floyd, to the pavement for 7 minutes and 46 seconds (the total time that knee pressure was applied, including time before the Frazier video began, was later calculated to be 9 minutes and 29 seconds.) When Chauvin began applying knee pressure to Floyd’s neck, officer Thomas Lane put pressure on his legs. Officer Thao stood nearby, in an apparent effort to separate bystanders from the unfolding scene. In the video, Floyd said “I can’t breathe”—sixteen times. He said, “My stomach hurts, my neck hurts, everything hurts.” He called out “Please” and “Mama.” Floyd at one point said, “I’m about to die.” Chauvin told him to “relax.” Concerned witnesses begged Chauvin to take his knee off of Floyd’s neck. Chauvin was unmoved. Thao was also unmoved, telling observers Floyd was “talking” and “he’s fine” and—seizing the moment for a public service announcement—“This is why you don’t do drugs.”

About five minutes into the video, Floyd appeared to be unconscious. Chauvin pulled out mace to keep worried bystanders from intervening. Thao moved directly between the bystanders and Chauvin. One observer demanded that officers check Floyd’s pulse. Officer Lane was concerned enough to twice ask Chauvin whether they should move Floyd to his side. Chauvin said no.

At 8:27 pm, with Chauvin’s knee still on Floyd’s neck, a Hennepin County ambulance, called to the scene by officers, arrived. Finally, after nearly nine minutes of applying pressure, Chauvin released his knee. Paramedics loaded the silent and unconscious Floyd onto a stretcher, carried him to an ambulance, and raced off for the Hennepin County Medical Center. Darnella Frazier’s video ends at this point. It is, arguably, the most consequential spontaneous video recording in history.

Aboard the ambulance, Floyd went into cardiac arrest. Paramedics requested that firefighters meet the ambulance at the corner of 36th Street and Park Avenue. Fire department medics found Floyd unresponsive and without a pulse. At 9:25 pm, Floyd was pronounced dead at the Hennepin Medical Center emergency room.

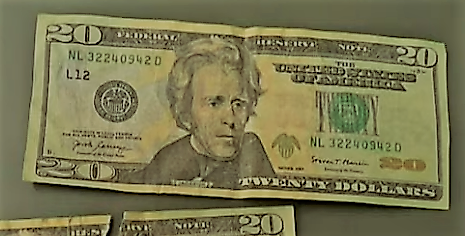

All over Twenty Dollars

The Minneapolis tragedy depicted in the video had begun when a Cup Foods employee called 911 to report that Floyd had purchased a pack of cigarettes with a counterfeit $20 bill. The employee said that Floyd was “awfully drunk” and “not in control of himself.”

Counterfeit $20 bill that led to Floyd's arrest

Minutes before the call, two Cup Foods employees had left the store to confront Floyd as he sat in the driver’s seat of his SUV at the intersection of East 38th Street and Chicago Avenue. They demanded Floyd return the cigarettes. Floyd refused.

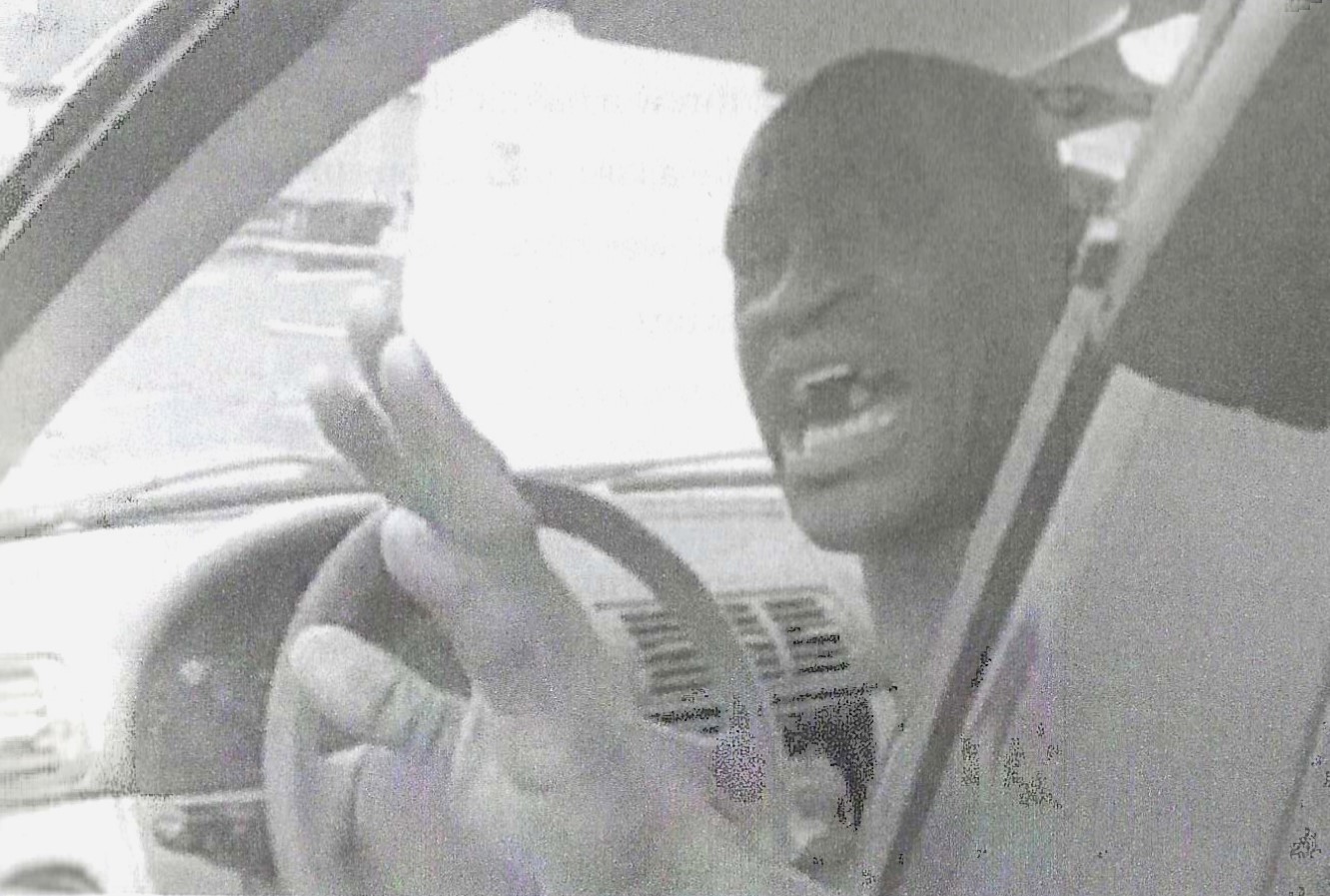

The first two officers to arrive on the scene were Thomas Lane and J. Alexander Kueng. Lane knocked on the window of a car in which Floyd was sitting (along with drug dealer Morries Hall and Shawanda Hill). Floyd had recently woken up after being unconscious for about 90 seconds, according to Hall. Lane drew his gun, swore at Floyd, and ordered Floyd to put his hands on the steering wheel. When he complied, Lane holstered his weapon. Floyd told Lane he was "hooping" (doing drugs) and later seemed to yell, "I ate too many drugs." (Although a prosecution witness would later suggest Floyd said, "I ain't do no drugs.") Floyd initially resisted Lane's command to exit the vehicle. From the backseat, Shawanda Hill shouted, "Stop resisting, Floyd!" Eventually, Lane removed Floyd from the vehicle and handcuffed him. Kueng brought Floyd over to the front wall of a restaurant and told him to sit down. A complaint filed later against the officers says that Floyd was “calm” and even said “Thank you” to the officers. Officer Kueng led Floyd over to a police car. Floyd, according to prosecutors, said that sitting in a car would be claustrophobic and that he did want to do that.

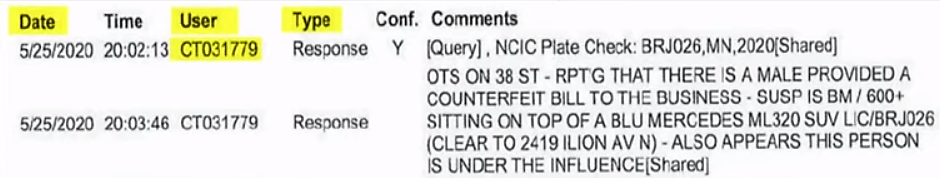

Two initial police dispatches regarding Floyd arrest

At 8:17 pm, a squad car carrying officers Derek Chauvin and Tou Thao arrived on the scene. Chauvin, the most senior of the four officers, took command of the situation. Kueng then struggled to load Floyd into the driver’s back seat of his vehicle, while officer Thao watched. Floyd appeared panicky, repeatedly telling officers, "I can't breathe." A minute or two later, video showed Chauvin pulling Floyd across the back seat and out the passenger side door. Floyd fell to the pavement, his chest on the ground. Then the awful scene recorded in Frazier’s video unfolded.

photo from the bodycam of Officer Lane which appears to show a pill in the mouth of George Floyd

The fact that Floyd insisted he could not breathe before Chauvin even touched him hints that many factors likely contributed to Floyd's breathing difficulties. An autopsy would reveal Floyd had fentanyl, meth, and other opioids in his system. The combination of drugs taken by Floyd can cause chest and neck muscles to stiffen, and that in turn can cause breathing to stop. Also, Floyd had contracted COVID the previous month and still tested positive in his autopsy. To make matters even worse, Floyd suffered from hypertensive heart disease as well as arteriosclerotic heart disease, problems that contribute to shortness of breath and other breathing problems. Floyd's drug ingestion and disease made it far more likely that the additional stress of an arrest and physical restraint would lead to a stoppage of breathing and ultimately death for him than would be the case for a typical arrestee. The initial Hennepin County autopsy report, prepared by Dr. Andrew Baker, indicated Floyd's cause of death was "cardiopulmonary arrest," and stated that "no injuries of anterior muscles of the neck or laryngeal structures" were observed.

George Floyd

George Perry Floyd came to Minnesota in 2017, hoping to make a fresh start. Floyd was born in North Carolina. His parents split up a few years later. Floyd and his siblings moved with his mother to a poor section of Houston called The Bricks. Friends in his Houston high school described “Big Floyd” as open, friendly, and funny. He starred in both basketball and football, and earned an athletic scholarship at South Florida Community College. He transferred two years to Texas A & M’s Kingsville campus, then quit school and entered a downward spiral of drugs and arrests that lasted almost a decade. In 1998, he was sentenced to ten months in prison for theft with a firearm. In 2002, 2004, and 2005, Floyd received additional sentences in jail for cocaine possession. Then, in 2009, Floyd plead guilty to charges of aggravated robbery with a deadly weapon. Floyd had held a gun to the stomach of a pregnant woman while other suspects searched the premises for drugs and money. Floyd spent four years in prison. He was released in 2013.

Floyd became involved in Resurrection Houston, a church that holds services on basketball court. When baptisms were held, church leaders turned to Big Floyd to drag the heavy baptism tub to the center of the court. He found a Christian program in Houston that took people north to Minnesota and provided them with access to jobs and drug rehabilitation programs. Floyd moved into a duplex with two roommates in the western Minneapolis suburb of St. Louis Park. By 2018, when he returned to Houston for his mother’s funeral, Floyd told friends and relatives that Minneapolis was beginning to feel like home. He worked as a security guard at a downtown Minneapolis homeless shelter and transitional housing facility operated by the Salvation Army. Former co-workers at the shelter described Floyd as kind and helpful, noting that he often volunteered to walk employees to their cars. He took a second job as a bouncer at Conga Latin Bistro, a downtown dance club. Conga’s owner said Floyd “became part of the family,” coming in early and leaving late.

In May, 2019, Floyd was arrested, following an undercover drug investigation, for selling more than 1,000 illegal oxycodone pills. At the time of his arrest, Floyd swallowed a number of pills. Also, similar to his 2020 arrest, Floyd acted erratically and refused to comply with police commands or to get out of his car. Defense attorneys would later attempt to use the 2019 arrest to suggest a pattern of criminal behavior and convince jurors that Floyd also swallowed pills at the time of his 2020 arrest--and that the pills and disease were the actual cause of his death, not the neck restraint applied by Chauvin. (Floyd's DNA was found on chewed up pills, containing fentanyl and methamphetamine, recovered from the back seat of Chauvin's police car.)

In the spring of 2020, Floyd contracted from the coronavirus. He spent more time with his girlfriends. He had not seen his roommates in the last few weeks before his May 25 arrest—and his last breaths.

The Four Officers

Officers Chauvin, Kueng, Lane, and Thao (right to left)

Derek Chauvin, age 44, was the commanding officer in the incident that led to Floyd’s death and was the field training officer for both Thomas Lane and Alexander Kueng, both of whom were in their first week of active duty. Chauvin was a nineteen-year veteran of the force, but had a checkered history that included eighteen complaints, two of which resulted in official letters of reprimand. But Chauvin also won two medals of valor and two medals of commendation. He was fearless, in various incidents single-handedly apprehending a group of gang members, tackling a fleeing suspect with a pistol, and breaking down a door to disable an attacker in a domestic violence situation. Chauvin grew up in Cottage Grove, Minnesota. Prior to joining the police force, he served two enlistments as a military policeman with the United States Army. While serving on the MPD, Chauvin also worked as a security guard at EL Nuevo Rodeo, a Latin nightclub. A former owner of the club said Chauvin sometimes used mace in dealing with the mostly black clientele when, in her opinion, dealing with the few people fighting would have more effectively addressed the problem.

People that knew Chauvin about the man described by a Minneapolis reporter as "an enigma." Sgt. Joey Sandberg, a friend and former co-officer in the Third Precinct said, “He’s not the devil that he’s made out to be. . . .I don’t know what happened to him. Nobody knows. That’s the million-dollar question.” Maya Santamaria, former owner of the El Nuevo Rodeo nightclub where Chauvin worked security for years, said Chauvin was usually a “mellow” guy, but was also quick to get aggressive. Santamaria said, “I saw both sides of him. Pepper spraying everybody, sometimes using holds that were not apparently the most legal of holds, getting freaked out if there were a lot of Black clientele in our club and needing backup right away for no apparent reason.” Chauvin was the subject of 17 misconduct complaints since 2001, but only one resulted in discipline. He also was involved in two other fatal encounters with civilians and two nonfatal police shootings.

Defending Chauvin, facing a vigorous prosecution, would be a challenging task. Eric Nelson took on the job. Nelson revealed that he would argue that Floyd died from chronic health problems exacerbated by drug use, not at the hand of Chauvin. Nelson said Floyd "was a daily smoker of cigarettes. His heart was at 'the upper limit of size' due to untreated hypertension. Mr. Floyd suffered from arterioclerotic and hypertensive heart disease." According to Nelson, the most likely cause of Floyd's death was "fentanyl or a combination of fentanyl and methamphetamine in concert with underlying health conditions."

The second most senior officer involved in Floyd’s arrest was Tou Thao, 34, who worked as a full-time police officer since 2008. Six complaints were filed against Thao, though none resulted in discipline. In addition as a rookie officer, Thao was cited eight times for dishonesty or sloppy practices.The most serious charge against Thao was a 2014 incident in which Thao allegedly assaulted the arrestee, landing his victim in the hospital. Thao was accused of punching, kicking, and kneeing an unarmed African-American. The Minneapolis Police Department settled a civil suit brought in that case for $25,000. Thao is a member of the Twin Cities’ large Hmong population, over 64,000 strong. In his interview with a Bureau of Criminal Apprehension (BCA) investigator after Floyd's death, Thao allowed that "I could have been more observant to Floyd.”

On August 14, 2020, prosecutors filed a one- hour-forty-minute video voluntary interview, conducted by Bureau of Criminal Apprehension special agent Brent Petersen, given by Tou Thao concerning the incident. In the interview, Thao focused on his concern for the safety of the other officers and tried to distance himself from Chauvin's actions. Thao said, “As the crowd is starting to grow and become loud and hostile toward us, I decided to forgo [monitoring] traffic and put myself in between the crowd and the officers … and just spend the majority of my attention looking at the crowd — make sure they don’t charge us or bull rush us." Thao described himself as a “human traffic cone.” Thao said Floyd he thought Floyd was on drugs, and that he resisted getting into a squad car and kicked himself out of the squad car and onto the street. He said Floyd's actions were making the other officers tired: “I could tell the officers on the ground were getting tired. Everyone’s breathing hard." Thao described the corner where the arrest took place as a gang hangout "especially hostile" to police. Agent Petersen asked Thao, "So that maneuver you saw officer Chauvin use, is that something you’ve been trained in?” Thao replied, "I've never used it.” Asked what he thought when he learned Floyd had died, Thao replied, rather unemotionally, “I don’t want anyone to die.” Asked why he didn't intervene to check on Floyd's pulse, Thao said, "My job is scene security.” He added, "God only gave me one body and two hands and two legs. I can’t be in two places at once.” Thao's attorney, Robert Paule, filed a motion to dismiss charges against his clients, arguing Thao's focus was on crowd control and he did not have his eyes on the actions of the officers pinning Floyd to the pavement. Prosecutors contested the motion, arguing that Thao was aware of what was happening, heard his cries, and acted to prevent concerned bystanders from intervening.

The two rookie cops at the scene, Alexander Kueng, 26, and Thomas Lane, 37, encountered Floyd on just their fourth shift. That fact alone is likely to make their convictions difficult, especially on the more serious charges. Attorneys for Lane and Kueng — Earl Gray and Thomas Plunkett — placed the blame for Floyd’s death squarely and solely on Chauvin, arguing that their clients looked to the veteran officer for guidance. Gray noted that Lane twice asked Chauvin if they should roll Floyd onto his side to help him breathe, but was rebuffed. Gray said he will ask for a separate trial: “I don’t anticipate trying Mr. Lane’s case with Mr. Chauvin." Attorney Friedberg saw the defense case for Lane as strong: “The things the young man [Lane] said out loud, the relationship between Chauvin and the young man, and it’s clear that young man had no intent for Floyd to die because he did CPR. That’s going to be a huge issue.” Other attorneys, however, expected that Chauvin would attempt to direct blame at the younger officers. Lawyer Robert Richman told the Star Tribune, "He could direct the blame at Lane, who was holding down Floyd’s leg as Floyd lay stomach-down in the street, and Kueng, who was holding onto Floyd’s back." Richman added, "It seems that keeping someone … in a prone position on your stomach and having pressure placed on your back causes respiratory difficulties.”

Thomas Lane's attorney filed a motion asking that all charges against his client be dismissed. Lane's attorney cited the transcript of police video cameras which show that Lane twice suggested to Chauvin that Floyd should be rolled over on his side, but that Chauvin curtly refused the suggestion. The transcript also suggests Lane shared concerns about Floyd's medical condition and did what he could in the ambulance to help revive him. But camera footage, released on July 15, raised troubling questions about the police response. The video showed that Officer Lane gave George Floyd no explanation for why they were questioning him before he pointed a gun, swore at him and forced him out of his vehicle. Floyd grew terrified and two minutes into the video began crying. Civil rights attorney Nekima Levy Armstrong, who viewed the video (available for viewing only by appointment), described what she watched as "horrifying." Armstrong said, “They did not treat George Floyd as if he was human from the moment they approached the vehicle — holding him at gunpoint, not listening to him, not taking his concerns seriously.” On August 18, Thomas Lane's attorney Earl Gray filed a 21-page attack on the charges against his client. Gray argued that Floyd's past criminal record, including a conviction for a 2007 robbery in Texas where he robbed a woman at gunpoint, and a 2019 arrest in which cocaine was found in his car, gave Lane and the other officers reason to doubt Floyd's veracity. According to Gray, “With this background in mind, the State’s suggestion that Officer Lane was required somehow to believe Mr. Floyd’s denial of culpability invites an adventure into Pollyana[sic] land.”

A one-hour-thirty-seven minute audio recording of a BCA interview of Thomas Lane was released in August. Lane said the officers’ decide to restrain Floyd with handcuffs, stomach-down, because he appeared to be on drugs. Lane said, “Once Floyd kind of stopped fighting us, I think I had said again, ‘I think we should roll him onto his side,’ and I believe Chauvin said, ‘We have him, there’s an ambulance coming and we got him. We’re just going to hold him here.’ ” Lane said that made sense to him "just because I’ve had experiences with people who are OD’ing or they’ll be out one minute and they’ll come back and really be aggressive with you.”

Alexander Kueng was one of 80 black officers (his father is from Nigeria, his mother is white) on the MPD force of 900. He joined the force, his mother told the New York Times, because he wanted "to bridge that gap in the community, change the narrative between officers and the black community." She says for her son "to be wrapped up in a racially motivated incident like this is just unfathomable." Kueng, she said, was always a doer. He joined his family helping at an orphanage in Haiti, and took a break from school to volunteer there after an earthquake struck the country in 2010.

Four Officers Fired, but All Hell Breaks Loose

On the morning after Floyd’s death, Frazier’s video was the most watched video on social media and was replayed over and over on both broadcast and cable news programs. The almost universal reaction to the video was shock. Not only did it seem to show a clear case of unjustified force, to many it seemed to be irrefutable evidence of a cold-blooded murder of a defenseless black man by a white officer.

The Floyd video came after a string of recent incidents and controversial videos that seemed to show racist conduct by either police officers or members of the public. In March, a 26-year-old emergency medical technician named Breonna Taylor was fatally shot by Louisville police officers executing a no-knock search warrant at her apartment. She was shot eight times. In early May, a video went viral that showed the gunning down by two white residents of Ahmaud Arbery, a 25-year-old African American man who was jogging near Brunswick, Georgia. Then, on the same day Floyd was killed a viral video showed a white woman in Central Park, asked to put her dog on a leash (as park rules require) by Christian Cooper, an African-American birdwatcher, responding by pulling out her cellphone and calling police. She tells Cooper, “I’m going to tell them there’s an African-American man threatening my life.” Tinder was piled high. The Floyd video was the match.

Officer Thao, keeping anxious bystanders away from Chauvin and Floyd

Officer Thao, keeping anxious bystanders away from Chauvin and Floyd

The day after the death of George Floyd, all four officers were fired from the Minneapolis police force. In announcing the terminations, Minneapolis Mayor Jacob Frey said, “It is the right decision for our city, the right decision for our community. It is the right decision for the Minneapolis Police Department.” Frey added, “For five minutes we watched as a white officer pressed his knee into the neck of a black man who was helpless. For five whole minutes. This was not a matter of a split-second poor decision.” Minneapolis Police Chief Medaria Arradondo, an African-American, told reporters during the news conference that he had asked the FBI to investigate the incident. A few weeks later, on June 23, the Chief elablorated on his decision in even more forceful terms. “Chauvin knew what he was doing," he said. “This was murder — it wasn’t a lack of training. This is why I took swift action regarding the involved officers’ employment with MPD.” Arradondo also told Leslie Stahl, in an interview for CBS's Sixty Minutes, that he believed even the rookie officers had a duty to intervene to end the choking of Floyd--with physical force applied against Chauvin if necessary.

George Floyd’s family, meanwhile, demanded murder charges be brought against the officers. That night, a crowd marched to the 3rd Precinct police headquarters. A clash broke out between protesters and police clad in riot gear. Police fired tear gas to disperse the crowd. It was just a mild skirmish compared to what would happen in the Twin Cities over the next three nights.

Red paint and the word "Murderer" on Chauvin's suburban driveway

On day two of the protests, thousands poured into the streets. The protests started peacefully, but descended into chaos after nightfall. Several buildings were set afire. A Target, Foot Locker, and other smaller businesses were looted. Police fired flash bang grenades and rubber bullets at rioters. Thick teargas drifted through neighborhood streets. Meanwhile, in the suburb of Oakdale, hundreds of protesters on Wednesday gathered outside the home of Officer Derek Chauvin. Someone poured red paint on his driveway and the word “killer” was written on his garage door.

The following morning, state and local officials to pled for peace. Representative Ilhan Omar, whose district covers much of the riot-torn area tweeted, “Violence only begets violence. More force is only going to lead to more lives lost and more devastation.” Police Chief Arradondo told media the majority of the protesters remained peaceful, and that the demonstrations had been “hijacked” by a relatively small number of looters, vandalizers, and arsonists.

Things got even worse on May 28, the third night of protests. Protesters overran the 3rd Precinct headquarters of the MPD on Lake Street and Minnehaha Avenue, pulling down a wire fence constructed to protect it. Officers abandoned the building and protesters set it aflame about a half hour later. The destruction of a police station is unprecedented in modern U.S. history. The last time a station was destroyed was during the New York Draft Riots of 1863. Among the other buildings burned was a six-story building under construction about a block away that was to provide nearly 200 apartments of affordable housing. A black woman watching the flames said, “We’re burning our own neighborhood. This is where we live, where we shop, and they destroyed it.”

The escalating protests captured the attention of President Donald Trump. Shortly before midnight he tweeted, “I can’t stand back & watch this happen to a great American City, Minneapolis.” He called the protesters “THUGS” and said either the “weak Radical Left Mayor” should bring the city under control “or I will send in the National Guard & get the job done right.” Trump also tweeted, “When the looting starts, the shooting starts”—a tweet that was flagged by Twitter for “glorifying violence.”

Before sending his tweets into cyberspace, President Trump spoke to Governor Walz, who was waiting for authorization from Mayor Frey to send in activated National Guard units. When the authorization came, and the guard was deployed on Minneapolis streets, a measure of order was restored after a fourth night of protests. The worst was over—for Minneapolis, that is.

Minnesota Governor Tim Walz

After first criticizing state officials, Trump later offered praise for Walz’s handling of the situation. Trump said, “I fully agree with the way he handled it the last couple of days. I asked him to do that. He had a lot of men.” Walz told the president the mobilization of the Guard had been one of the largest in the state’s history. In their phone conversation, Trump replied, “But Tim, it shows the incredible difference between your great state yesterday and the day before compared to the first few days which was just a [inaudible].”

Protests Spread Beyond Minneapolis

But the George Floyd protests were really just beginning, spreading from city to city. By early June, protests had been held in all fifty states. . Many protesters echoed the words of George Floyd, and chanted “I can’t breathe!” While most protests were non-violent, some turned ugly, especially after sundown. Protesters burned police cars, charged police stations, smashed windows, looted, and set fires, in cities from New York and Atlanta to Portland and San Jose. Two hundred cities imposed curfews and over 60,000 National Guard personnel were activated. Property losses climbed into the billions. Over twenty lives were lost, not counted some additional number whose involvement in demonstrations might have caused them to contract fatal cases of Covid.

President Trump threatened to deploy the army to quell the unrest, a move that would require invoking the Insurrection Act of 1807. On June 3 he said, "If a city or state refuses to take the actions necessary to defend the life and property of their residents, then I will deploy the United States military and quickly solve the problem for them." The threat, however, was never carried out.

Protests also spread from nation to nation, continent to continent, with protesters rallying against both police brutality and racial discrimination. Nationwide, protests peaked on June 6, when on that single day more than half a million people took to the streets in nearly 550 locations. Polls suggest that somewher around 20 million Americans protested in the weeks following Floyd's death, making the Floyd/Black Lives Matter protests the largest movement in the history of the United States.

American Indian Movement (AIM) protesters pull down a statue of Christopher Columbus in St. Paul

The movement set in motion by Floyd’s death even had consequences for monuments across the world that had stood for decades. Statues memorializing Confederate leaders and other famous people associated with racist causes began to be toppled: General Stuart in Richmond, Edward Colston in Bristol, Christopher Columbus in St. Paul. On June 19, the statue of Confederate Gen. Albert Pike, which had stood in Washington D.C.’s Judiciary Square, was toppled. The number of monuments were either toppled, vandalized, or removed and placed into storage grew into the hundreds. Portraits came down too. On June 18, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi had ordered the removal of four portraits from the Capitol building each depicting a former Speaker of the House that served the Confederacy. The next day, in Minneapolis, at Target Field, home to the Minnesota Twins, a statue of Calvin Griffith was taken down. Griffith, a former owner who moved the Washington Senators to Minnesota in 1961, had been quoted in 1978 as saying, ""I'll tell you why we came to Minnesota. It was when we found out you only had 15,000 blacks here. Black people don't go to ballgames, but they'll fill up a rassling ring and put up such a chant it'll scare you to death. We came here because you've got good, hardworking white people here." Griffith had to come down. It was also announced the same day that Calhoun Square, a large retail center just two miles from the site of Floyd's arrest, would change its name. People had often wondered why a shopping district in Minneapolis was named after a southern senator who fought to preserve slavery. Consequences of the movement set in motion by Floyd's death even reached Mississippi, where state legislators voted to remove the Confederate battle emblem from the upper right-corner of the state flag, where it had been since 1894.

The statute toppling trend was bound to reach a point of absurdity, and it soon did. On June 19, protesters in Portland tore down a statue of George Washington (because he owned slaves) and in San Francisco a statue of Ulysses S. Grant, arguably the best friend in the White House African-Americans ever had in the nineteenth century, came tumbling down. The ignorant and provocative behavior seemed all but certain to provoke a backlash that could only hurt the movement. In Trump's first re-election rally in Tulsa on June 20, President Trump was quick to point to the tearing down of the George Washington Monument in Seattle, as well as the occupation of part of that city by anarchic protesters, as signs of what will happen everywhere in America if Joe Biden is elected president in November. While polls taken after Floyd's death show a substantial majority of Americans see racial discrimination in law enforcement as a serious problem that should be addressed, it's likely not 5% of Americans supported the burning or toppling, say, of George Washington statues.

By mid-July 2020, much of the nation's focus on the protest movement shifted to Portland, Oregon, where Border Patrol SWAT teams from the agency’s BORTAC tactical unit faced off against protesters including anarchists wielding fireworks, laser pointers and slingshots. In Portland, the federal law enforcement units continued to patrol streets for weeks, based on a claimed need to defend the federal courthouse. Democratic officials in Oregon asked the Trump administration to withdraw from Portland, arguing that the tactics of DHS agents have exacerbated tensions.

President Trump refused the request by Oregon officials to withdraw troops, including those in unmarked uniforms and cars that had prompted comparisons with fascist regimes. Trump called the unrest in Portland “worse than Afghanistan,” and threatened to send federal agents into other cities experiencing unrest in the wake of Floyd's death. “We’re looking at Chicago, too. We’re looking New York,” Trump told reporters on July 20. “All run by very liberal Democrats. All run, really, by the radical left. . . .This is worse than anything anyone’s ever seen,” Trump said. “And you know what? If Biden got in, that would be true for the country. The whole country would go to hell.”

Charges Upgraded and Pre-Trial Developments

On June 3, Minnesota Attorney General Keith Ellison upgraded the charge against Chauvin to second-degree murder and charged the other three officers at the scene with aiding and abetting murder and manslaughter. The decision came two days after, at the request of Governor Tim Walz, Ellison took over the prosecution from Hennepin County Attorney Mike Freeman, who seemed to Ellison insufficiently committed to a vigorous prosecution. The three former officers who were present but failed to intervene were booked into the Hennepin County jail. The prosecution of the four officers was begun quicker than any case in Minnesota history involving officers on the job who killed civilians. Chauvin said of his and charges, "I'm here because of perceived racism and politics."

Speaking to the press, Ellison said, “To the Floyd family, to our beloved community, and everyone that is watching, I say: George Floyd mattered. He was loved. His life was important. His life had value. We will seek justice for him and for you and we will find it.” In response to a question, Ellison dismissed the idea that intense public pressure affected the process.

Minnesota Attorney General Keith Ellison announcing new charges in the Floyd case

Governor Walz said after the new charges were announced, “I laid flowers at George Floyd’s memorial this morning. As a former high school history teacher, I looked up at the mural of George’s face painted above and I reflected on what his death will mean for future generations. What will our young people learn about this moment? Will his death be just another blip in a textbook? Or will it go down in history as when our country turned toward justice and change?” He added, “It’s on each of us to determine that answer.”

Benjamin Crump, an attorney representing Floyd’s family, Benjamin Crump, also commented on the charges against the officers. He said the move was “a significant step forward on the road to justice” and expressed gratitude that “this important action was brought before George Floyd’s body was laid to rest.”

Few people knew at the time how close the case against Derek Chauvin came to being closed before it even began. Not until February 2021 was it revealed that three days after George Floyd's arrest, at a time when soldiers were preparing to take to the streets, officer Derek Chauvin concluded that the case against him was so strong that he agreed to plead guilty to third-degree murder, a conviction that could have resulted in more than 10 years of jail time. Under the deal, Chauvin would serve his time in federal prison and be assured that no additional federal civil rights charges would be brought against him. But just before local officials could announce the deal, it fell apart because it was rejected by Attorney General William Barr, who worried that a plea deal, so early in the process and before a full investigation had concluded, would be perceived as too lenient by the many protesters across the country.

On June 4, attorneys for two former rookie Minneapolis police officers, Hueng and Lane, said that any blame for the killing of George Floyd rested on Officer Chauvin, the senior officer who they said ignored their inexperienced clients.

J Alexander Kueng, Thomas K. Lane, and Tou Thao made their first court appearances. Hennepin County District Judge Paul Scoggin set bail for each of the other three at $1 million without conditions, or $750,000 with conditions. The bail hearing turn contentious when Lane’s attorney, Earl Gray, argued, “What is my client supposed to do but follow what the [senior] officer says? What was [Lane] supposed to do … go up to Mr. Chauvin and grab him and throw him off?” Gray noted that his client twice asked Chauvin if they should roll Floyd on to his side, but Chauvin rebuffed the suggestion. Lane’s attorney called the strength of the state’s case “extremely weak.” Kueng’s attorney, Thomas Plunkett, made similar arguments. Plunkett told the court, “[Kueng] was trying — they were trying to communicate that this situation needs to change direction.” On the other hand, Thao’s attorney, Robert Paule, made no attempt to shift blame to Chauvin, his client’s partner.

Assistant Attorney General Matthew Frank countered by arguing that the charges were “very serious” and that the officers were “flight risks.”

Gray indicated he would file a motion to argue that there’s not enough evidence to prosecute Lane. Asked whether Lane had a duty to get Chauvin off Floyd’s neck, Gray said, “I guess the jury will decide that. In my opinion, no. It would be unreasonable for my client to go up and drag Chauvin off the deceased. … You’ve got a 20-year [sic] cop in the front and my guy’s back there with four days and he says, ‘Should we roll him over?’ and [Chauvin] says, ‘No, we’ll wait for the ambulance’ twice. … I don’t know what you’re supposed to do as a cop.”

On June 12, Hennepin County District Judge Peter Cahill was assigned the unenviable task of trying the MPD case. Cahill began his career as a defense attorney before serving as the top staff attorney to U.S. Sen. Amy Klobuchar when she was county attorney. He was appointed to the bench by Governor Tim Pawlenty. Cahill has tried a number of high-profile cases and has a reputation for being decisive and direct. Cahill's first decision in the case was to reject a defense request to allow camera in the pretrial hearing. Cahill noted that Minnesota court rules require both the defense and prosecution to agree in order for cameras to be admitted. The judge also wrote in his June 26 order that "Given that this is a case that has already received substantial pretrial media coverage, the Court finds that audio or video coverage of the pretrial hearings. . . would risk tainting a potential Hennepin County jury pool.”

Attorney Thomas Plunkett and his client (center), Alexander Kueng

Federal Probe into Floyd's Death

Federal authorities began an inquiry into Floyd's death almost as soon as state authorities did. They sought to determine whether one or more of the officers could be charged with depriving Floyd of "rights under color of law." Color-of-law cases are difficult to prove because prosecutors must convince jurors that the officers knew what they were doing was illegal, but they did it anyway. In addition, the situation must be considered from the standpoint of "a reasonable law enforcement officer at the scene," not an objective, neutral observer. In most cases, federal charges are a backup to state charges. Charging officers with a federal crime so soon after the incident would be a departure from past practice. According to former U.S. Attorney for Minnesota Thomas Heffelfinger, the government "would be forfeiting, to some degree, the advantage of patience." In February 2021, federal prosecutors in Minneapolis convened a grand jury to consider federal charges against Derek Chauvin. U.S. Attorney Erica MacDonald said the case a top priority for the Justice Department and that the investigation “must be done right.” The Justice Department investigation ran parallel to the state case.

Remembering Floyd

At the place where Derek Chauvin’s knee met George Floyd’s neck, a memorial to Floyd grew from a few flowers and signs to something much larger. A large painted blue and orange mural, featuring Floyd, appeared on an outer wall of Cup Foods. A wooden sculpture of an upraised fist, the symbol of the Black Lives Matter movement, appeared in the center of the intersection.

In the days that followed Floyd’s death, the tribute became a place for thousands of people, somewhere to gather and try to express nearly inexpressible feelings. The site also became a center for Black Lives Matter protest and television correspondents used at as a backdrop for news stories.

The MPD announced they had no intention to alter or decommission the memorial of Floyd, tweeting “We respect the memory of him and will not disrupt the meaningful artifacts that honor the importance of his life.” There is an expectation that the memorial at East 38th Street and Chicago Avenue will evolve into a permanent tribute of some sort.

Rev. Sharpton speaking at the Minneapolis memorial for Floyd

On Thursday, June 4, a celebration—both somber and defiant—of Floyd’s life took place in a chapel on the campus of North Central University in Minneapolis. Floyd’s brother, Philonise Floyd, said of George, “Everywhere you and see people, they wanted to be around him.” A cousin said the thing she would miss most about George was his big hugs. Benjamin Crump, a civil rights lawyer representing the Floyd family, said George was killed by “the pandemic of racism.” Reverend Al Sharpton said black people have had to live with a knee on their necks for “401 years.” He said, “George Floyd’s story has been the story of black folks.”

In the days that followed, two more memorial services took place for Floyd. One in Houston, the city where he spent most of his life, and the second in Raeford, North Carolina, Floyd’s birthplace.

On June 9, a carriage pulled by two white horses carried George Floyd's body, in a gold-colored casket to a cemetery in the Houston suburb of Pearland on Tuesday, where Floyd was buried next to his mother.

Floyd's Death Leads to Policing Reform

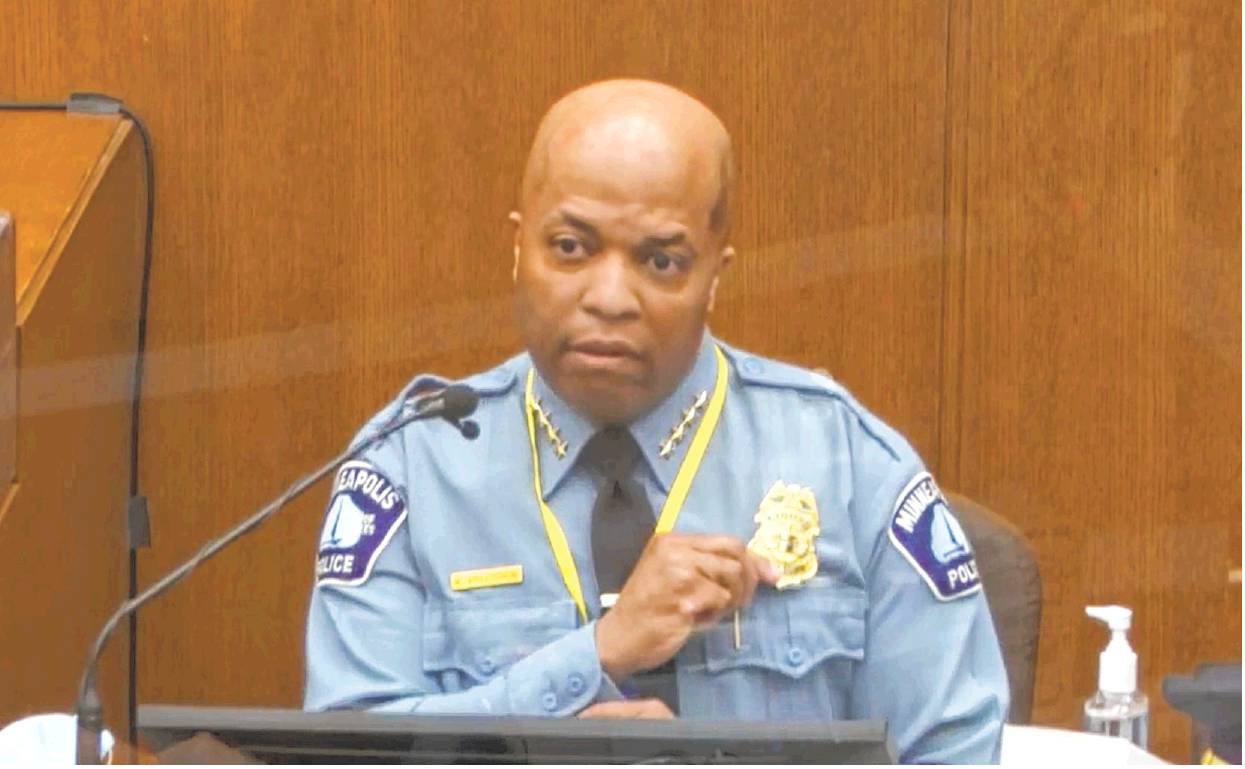

Minneapolis Police Chief Medaria Arradondo

Two weeks after Floyd’s death, The House Public Safety and Criminal Justice Reform Division of the Minnesota legislature began considering proposals to reform police practices and use-of-deadly-force cases. Floyd’s nephew asked the committee to ban chokeholds, a proposal that has bipartisan support. The sister of a man Chauvin shot in 2008 called for greater transparency concerning the handling of officer complaints. Another proposal under consideration would put prosecution of deadly officer-involved cases in the hands of Attorney General’s office. The association that represents Minnesota county attorneys voted to support the proposed change. Another proposal, with primarily Democratic support would change the state’s use-of-force standard. Under the proposal, force could only be used when the risk of death or great bodily harm to an officer or another person is “imminent”, as opposed to the current language which allows force when the risk is “apparent.”

On July 21, 2020, Minnesota legislators, in special session, passed legislation that substantially changed the state’s criminal justice system. The legislation included a ban on chokeholds and neck restraints — such as the one used on Floyd. It also prohibited warrior-style training for officers, improved data collection relating to deadly force encounters, required officers to intervene in life-threatening situations such as the one involving George Floyd, and created a new state unit to investigate such cases. Finally, the legislation created a panel of expert arbitrators to handle police misconduct cases and established incentives for officers to live in the communities they police.

Mayor Jacob Frey being jeered by protesters for not supporting defunding of the MPD

A majority of the Minneapolis Council suggested taking reform to a more radical level, declaring their intention to completely defund the MPD and replace it with something new—perhaps neighborhood-based entities charged with not only securing the peace, but social justice as well. Mayor Frey, however, indicated that he opposed abolishing the MPD.

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell said the House bill “is going nowhere in the Senate.” Republicans rallied around legislation that focused on improved officer training in uses of force, discourage the use of chokeholds, and establish a system for local departments to better report police-citizen encounters that result in serious injury or death. But, on June 23, Senate Democrats said they also had the votes to block the weaker Senate bill from getting the necessary 60 votes to advance. It's an election year and everyone wants to play politics, so it seems unlikely even modest reforms will be able to make it through Congress in 2020.

Not to be left out, Donald Trump, on June 17, signed an executive order, adopting ideas from the Senate plan, that encouraged better police practices and created a national database to track officers with a history of excessive use of force complaints.

Pre-Trial Developments

The months that followed were eventful ones, as the country dealt with the worst pandemic in over a century, a hotly contested presidential election, and an insurrection at the Capitol by Trump supporters protesting an election they believed was stolen.

Meanwhile, in Minneapolis, Judge Peter Cahill sorted through hundreds of motions by prosecutors and attorneys representing the four officers. Perhaps the most important issue Cahill considered was whether the four officers should be tried separately or together. The prosecution proposed to try all four men in one trial. The prosecution based its argument for a single trial on potential harm to witnesses and family members who "are likely to be traumatized by multiple trials" and "would allow the community and the nation to absorb the verdicts for the four defendants at once." Attorneys for the four officers objected, arguing for separate trials. Chauvin's lawyer, Eric Nelson, argued that the other three officers may collude in an attempt to place all blame on his client. Nelson said, “As is evident from pretrial pleadings, the other three defendants are prepared to place the blame for Mr. Floyd’s death squarely on Mr. Chauvin’s shoulders.” Nelson continued, “Mr. Chauvin will be required to defend the case differently from the other defendants. While they will need to cast doubt on their knowledge of Mr. Chauvin’s alleged intent — which, as is evident from their pretrial pleadings, they have already begun to do — Mr. Chauvin will need to dispute that he intended to assault Mr. Floyd.” Nelson argued for a single trial for his client and a joint trial for the other three officers.

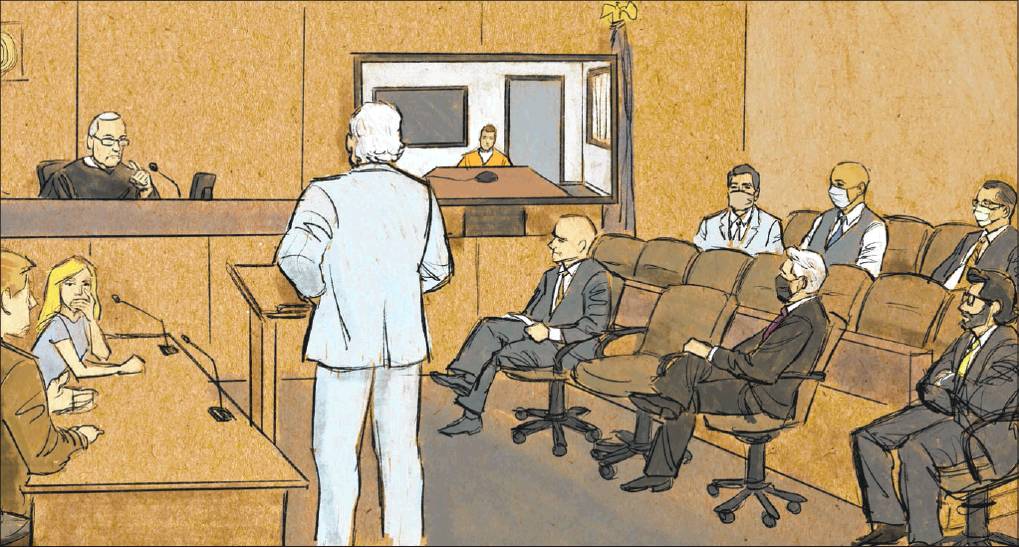

Judge Cahill presides at a pre-trial hearing in July 2020.

On September 11, Judge Cahill held a three-hour-plus hearing attended by all four defendants, to consider the separate trial issue and other trial-related matters. Protesters gathered around the courthouse before the session started. The group set up a sound system and microphone. What followed was nearly four hours of music and emotional speeches. The crowd chanted, “Indict, convict, send those killer cops to jail! The whole damn system is guilty as hell!” When the defendants tried to make their way to their cars after the hearing, they were accosted by angry protesters.

Judge Cahill initially sided with the prosecution, ruling in November that all four officers would stand trial together. Cahill said that "they acted in concert with each other, and the evidence against them is similar, so it is right to try them in one trial.” The judge also denied a defense motion to move the trial out of the Twin Cities--at least for now, leaving open the possibility of a change in venue if it becomes impossible to seat an untainted jury because of the tremendous amount of pre-trial publicity. Cahill said, “The murder of George Floyd occurred in Minneapolis, and it is right that the defendants should be tried in Minneapolis.”

In January, Judge Cahill reversed himself. He ruled that Derek Chauvin would be tried separately from the other three officers and set Chauvin's trial date for March 8. Cahill set the trial for officers Kueng, Lane, and Thao as August 23, 2021. The judge said that, for those three officers, the defendants’ defenses “will substantially overlap” and that separate trials would be complex and place an “undue burden” on state prosecutors and the court system. Minnesota Attorney General Keith Ellison said in a statement that he “respectfully disagreed” with the court’s decision, arguing that multiple trials “may retraumatize eyewitnesses and family members” and taint subsequent jury pools.

In other important rulings, Cahill decided that the trials would be live-streamed. Cahill wrote, “Without question, deprivation of the constitutional rights that are the hallmarks of a public criminal trial would be a ‘manifest injustice. The only real issue then, is whether there is a reasonable alternative to televising the trial that would vindicate the defendants’ Sixth Amendment rights and the First Amendment rights of the public and the press. … The Court concludes that televising the trial is the only reasonable and meaningful method to safeguard the Sixth and First Amendment rights implicated in these cases.” Cahill cited the size of the Hennepin County courtrooms and the “unique and unprecedented situation” brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic as justifications for his decision.

A protester yells at former officer Thomas Lane, as he leaves the courthouse on September 11, 2020

Cahill also disposed of numerous motions related to evidentiary questions. Cahill was unsympathetic to a plan by three defense attorneys to introduce evidence that Floyd was involved in a 2019 drug case in Minneapolis and a 2007 drug-related robbery in Texas. Cahill asked, “What is the possible relevance of that [Texas] case in this case?” Cahill ruled against admitting evidence of either case, but cautioned the prosecution that if it argues at trial that Floyd had not ingested drugs around the time of his death, then defense attorneys could again request to admit evidence from the prior cases.

In another key ruling regarding the admissibility of past incidents in Derek Chauvin's police career, Cahill decided that two incidents of alleged excessive use of force by Chauvin could be admitted, while several other incidents in which Chauvin used a neck or head restraint on a civilian could not be introduced. Judge Cahill also ruled that defense attorneys could not introduce certain evidence relating to a 2019 arrest of George Floyd during a traffic stop (during which Floyd swallowed pills and required transport to a hospital), or evidence of his conviction for aggravated robbery when he lived in Texas. The two incidents involving Chauvin's checkered career as a police officer that would be admitted include a 2015 incident in which Chauvin and other officers responded to a suicidal and intoxicated male. Other officers used a stun gun on the male and placed him in a “side-recovery position.” Medical professionals later told the officers that if they had restrained him longer or delayed transporting him to a hospital he could have died. Also admissible is evidence relating to a 2017 incident in which Chauvin placed his knee on a female’s neck while she lay on the ground. Prosecutors wrote in a court filing that Chauvin kept his knee on her neck “beyond the point when such force was needed.” Cahill also denied the prosecution’s request to admit evidence about nine incidents involving Officers Thao and Kueng.

A late wrinkle was thrown into defense strategies for the trials when prosecutors announced on February 4 their intention to add third-degree murder charges against all four officers. Trial observers called the late prosecution effort to add a third-degree murder charge a strategic move to give jurors more opportunities to convict Chauvin against a history of public deference toward officers’ legal right to use deadly force on the job. Law professor Joseph Daly told the Minneapolis Star: “I think they’re afraid he’s not going to be found guilty of murder in the second degree, and [jurors will] go straight to manslaughter, and what [prosecutors] think is what he did is much more serious than manslaughter. They want to include all possible offenses that could arise from these facts.” Prosecutors said their decision to add the charge was based on a new appellate court ruling that upheld a third-degree murder conviction involving a Minneapolis police officer to fatally shot an Australian woman, Justine Damond, in 2017. Judge Cahill had previously dismissed the third-degree charge against Chauvin. Cahill cited state law saying that “a third-degree murder charge can be sustained only in situations in which the defendant’s actions ... were not specifically directed at the particular person whose death occurred.”

Judge Cahill rejected the state's request to add a third-degree murder charge for Derek Chauvin, noting that the appeallate's court ruling had not become final, and therefore precedential. But the Minnesota Court of Appeals ruled on March 5 that Cahill erred in refusing the prosecutors' request to add third-degree murder against former Chauvin. (Minnesota sentencing guidelines call for identical presumptive prison terms for second- and third-degree murder, but second-degree murder is punishable by up to 40 years in prison and third-degree murder is punishable by up to 25 years.)

Normally, prosecutions in Minnesota are reviewed and led by county attorneys for the jurisdiction in which the crime occurred. But in this case, the prosecution effort was directed by Minnesota Attorney General Keith Ellison. As the tral opening approached, the prosecution team of about 13 outside attorneys (all working for free) assigned to committees covering different topics (law enforcement and policing, medical issues, causation of death) continued to meet. Prosecutor Steve Schleicher said of the unprecedented state effort, “It was not a pirate ship, it was a warship, and it was ready to go.” The mantra for the prosecution, credited to special prosecutor Jerry Blackwell, was "You can believe your eyes."

Defense attorney Eric Nelson was forced to deal with many obstacles, some of which were ethically questionable, put in place by the prosecution's "dream team" of lawyers. For example, the prosecution put together a witness list of over 300 people, even though only thirty would eventually testify. The apparent strategy of the prosecution was to "conflict out" (create conflicts of interest) as many medical and forensic experts as possible, making it difficult for the defense to obtain its own witnesses. Also, when asked to supply (as the prosecution was required under the law to do) Bureau of Criminal Apprehension files relating to the case, which the prosecution had on an organized and searchable disk drive, the prosecution opted instead to supply Nelson with a single 6,000-page unsearchable file, causing Nelson to have to spend more than 150 hours hand-organizing the massive document.

The Trial of Derek Chauvin

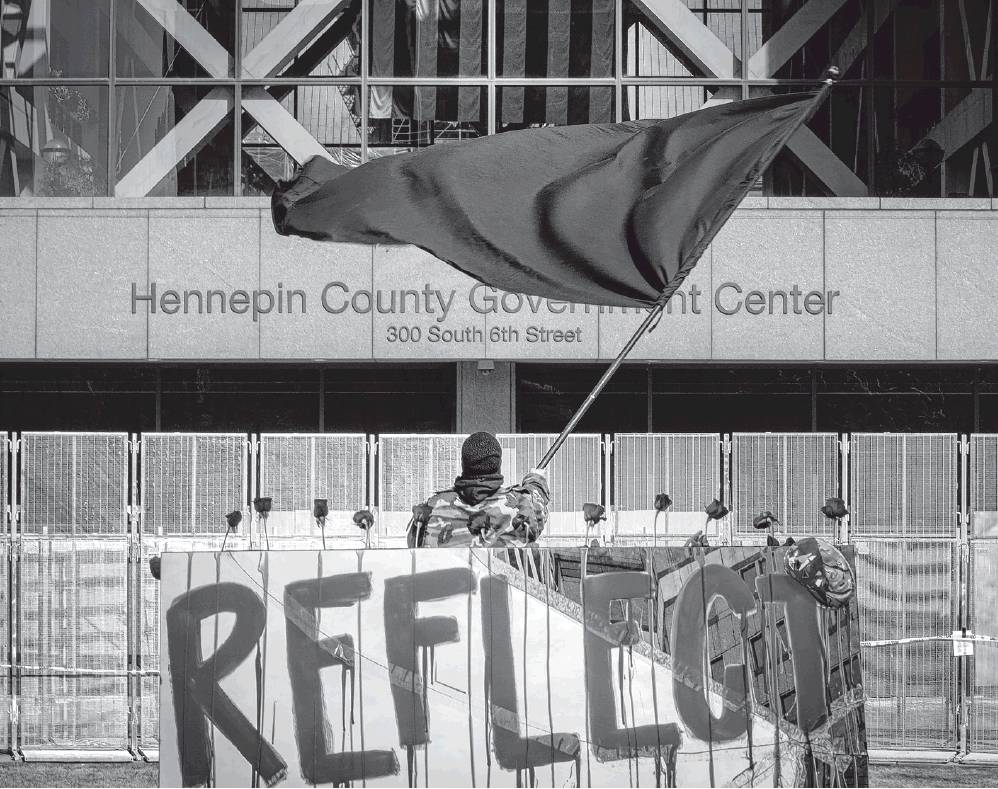

On March 8, 2021, on an unusually warm Minnesota day, the trial of Derek Chauvin opened in the heavily fortified Hennepin County Government Center. A crowd of about one thousand peaceful protesters, almost all hoping for a conviction in the case, gathered outside the building in downtown Minneapolis. They chanted: “No more killer cops!” and “Ain’t no power like the power of the people!” And they held banners: “The world is watching.” “Justice for stolen lives.”

Protesters gather in downtown Minneapolis as the Derek Chauvin Trial opens on March 8, 2021 (R. Tsong-Taatari, Minneapolis Star Tribune)

Inside the courthouse, jury selection had been temporarily halted, as prosecutors and Chauvin's attorney Eric Nelson argued over whether the trial should be postponed because of uncertainty as to whether a third-degree murder charge would be reinstated. Assistant Attorney General Matthew Frank argued that Chauvin’s trial should be suspended since Nelson plans to ask the Minnesota Supreme Court to review whether the charge is appropriate in Chauvin’s case. “We’re not trying to delay this case,” Frank said. “We want to try it right, and we can only try it once.” (Two days later, the Minnesota Supreme Court would not review the lower court decision that strongly suggested Judge Cahill should consider allowing the the third-degree murder charge to be prosecuted. The following morning, Cahill did just that, reinstating the third-degree murder charge. Attorney General Ellison welcomed the development. He said, “The charge of third-degree murder, in addition to manslaughter and felony murder, reflects the gravity of the allegations against Mr. Chauvin. We look forward to presenting all three charges to the jury.” )

Chauvin, dressed in a navy blue suit and tie and wearing a black mask, observed the arguments closely, sometimes taking notes on a yellow legal pad and occasionally conferring with one of his two attorneys..

A lone protester waves flag outside the Hennepin County Government Center on the opening day of the Chauvin trial.

By the end of the second day, the first three jurors were seated. (For profiles of seated jurors, click on the link to article "The Jury in the George Floyd Murder Trial" in the "Other Resources" column to the right.) By the end of the first week, a total of seven jurors were seated. Prosecutors had used 9 of their available 15 peremptory challenges, while the defense had used 8 of their strikes.

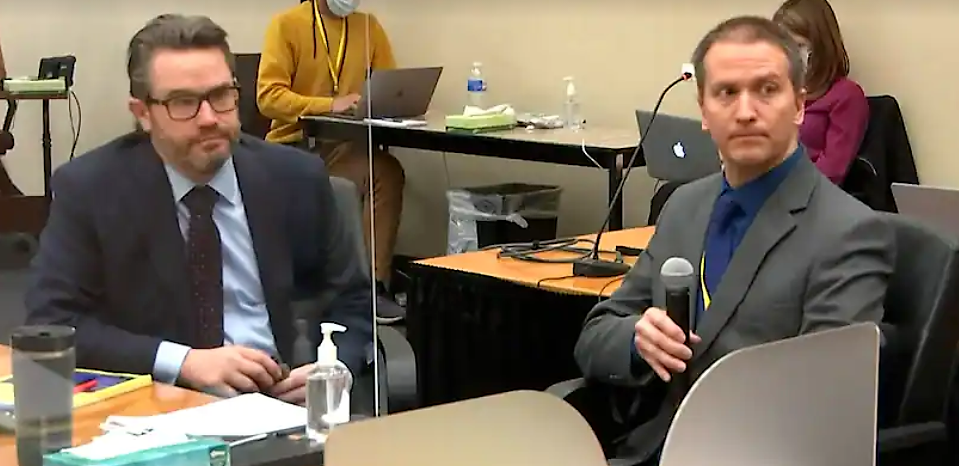

Derek Chauvin (right) and his attorney, Eric Nelson, on the opening day of the trial

At the end of the first week of jury selection, an announcement was made that threatened to delay the trial. The Minneapolis City Council signed off on a record $27 million settlement with the Floyd family in connection with a civil suit brought for the allegedly wrongful death of George Floyd at the hands of Officer Derek Chauvin. The timing of the announcement either reflected ignorance on the part of the Council of the consequences of their action for a fair trial or, at worse, a deliberate attempt to prejudice the jury in the Chauvin trial. Chauvin's attorney, Eric Nelson said, "I am gravely concerned with the news that broke on Friday related to the civil settlement." He called the timing "very suspicious" and said that it had an "incredible propensity to taint the jury pool." Prosecutor Steve Schleicher said, "We cannot control the civil aspect of the case, we cannot and do not control the Minneapolis City Council." Judge Cahill called the timing of the settlement announcement troubling. He asked Schleicher, "You would agree it's unfortunate, wouldn't you, that we have this reported all over the media when we're in the midst of jury selection?" The following day, the judge quizzed each of the nine seated jury about the civil settlement and how it might influence their view of the evidence. As a result of the interviews, Judge Cahill dismissed two jurors, a Hispanic man in his 20s and a white man in his 30s.

Prosecutor Steve Schleicher questions a potential juror on the fourth day of the Chauvin trial

The jury selection process was completed sooner than many people expected, with fifteen potential jurors selected by March 22. Two of the fifteen selected would serve as alternates and the fifteenth and last juror selected would be dismissed at the start of the trial unless one of the other fourteen were to become unavailable. The selected jurors included nine women and six men, nine whites and six people of color. They ranged in age from their 20s to their 60s. The group includes a chemist, an auditor, an information technology manager, a health care executive, a banker, a corporate consultant, a nurse, an insurance agent, a social worker, and an accountant. All jurors had seen photographs or video of Floyd's arrest. Most admitted on their 14-page juror questionnaire to having at least a "somewhat negative" view of Officer Chauvin, but all said they could decide his guilt or innocence strictly based on the evidence presented in court.

The Chauvin jury was surprisingly diverse for a Twin Cities jury. Whites make up 74% of the population of Hennepin County. Blacks represent just 14% of the county population, yet make-up a third of the jury. St. Paul defense attorney A. L. Brown said, “Anyone who’s tried a case in Hennepin or Ramsey County knows you’re not going to find six people of color on one jury. … I don’t know how that came to be,” Brown said. He added, “It’s certainly a good thing, but this is a unicorn jury given the level of diversity that you see in it.” Professor Joseph Daly of the Mitchell Hamline School of Law in St. Paul was pleased to see such a diverse jury selected for the trial: “I think it should give some people more confidence that this will be a fair process. Maybe we just lucked out in terms of getting a broad cross-section of people on the jury. … It does surprise me, and I’m glad.”

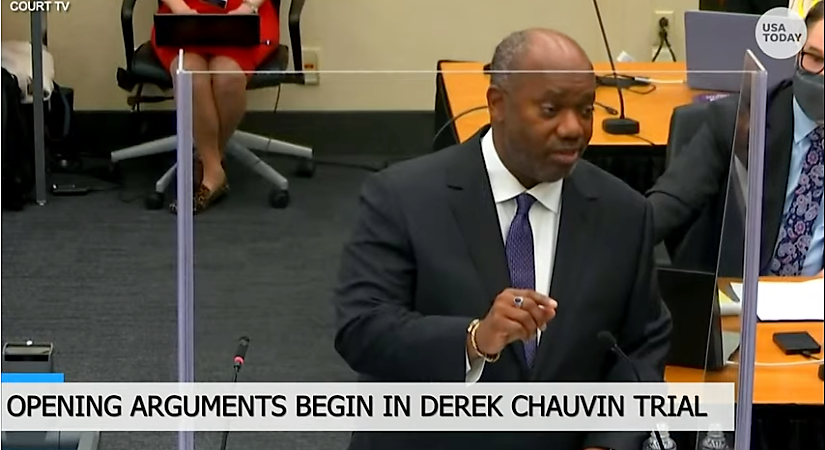

Prosecutor Jerry Blackwell presents his opening argument for the state on March 29, 2021

On the morning of March 29, a crowd of about 300 people gathered outside the courthouse to listen to speakers, including the Rev. Al Sharpton and Ben Crump, lawyer for the Floyd family. Crump said, “Today is the start of a landmark trial that will be a referendum on how far America has come on its quest for equality and justice for all.” Sharpton, Crump, members of the Floyd family and others knelt for nearly nine minutes in honor of Floyd, about the same length of time Chauvin knelt on Floyd’s neck. On the other side of the fences surrounding the barricaded Hennepin County Government Center, National Guard soldiers looked on.

About 9:30 am, oral statements began in the Chauvin trial. Jerry Blackwell, for the prosecution, delivered about hour-long address to the jury. He told the jury that the evidence would show that as George Floyd, handcuffed, non-resisting, and calling out 27 times that he couldn’t breathe, Officer Chauvin continued to grind and crush Floyd’s neck for nine minutes and 29 seconds, leading to his death. He told jurors that what Floyd did was a violation of his oath as an officer, and a violation of the Minneapolis Police Force’s policies on use of force. He said that the chief of the police force will tell them exactly that. Blackwell played a long, excruciating segment of a video filmed by a bystander. One juror gripped her armrest as she watched. “You can believe your eyes that it's a homicide,” Blackwell said. “It's murder.”

Eric Nelson presented the defense’s opening statement, telling jurors that three officers struggled to control Floyd and urging jurors to use common sense and reason. “You will learn that Derek Chauvin did exactly what he was trained to do over the course of his 19-year career,” Nelson said during his 20-minute presentation. “The use of force is not attractive, but it is a necessary component to policing.” Nelson said, “There is no social or political cause in this courtroom.”

Testimony from three prosecution witnesses followed. The state’s first witness of the trial was the 911 dispatcher, Jena Scurry, who handled the call that sent Chauvin and the other officers to Cups Foods, where Floyd had allegedly attempted to pass a counterfeit $20 bill. Scurry testified she was troubled by seeing on dispatch screens how Floyd’s arrest played out on city surveillance cameras. Seeing no movement for what seemed like a long time, Scurry said, “I first asked if the screens were frozen.” She said her “gut instincts” told her that “something was not right.” Her call to the shift sergeant was played in court: “I don’t know, you can call me a snitch if you want to but we have the cameras up for [squad] 320’s call, and … I don’t know if they had to use force or not.”

Witness Donald Williams demonstrates how Chauvin placed his knee on Floyd's neck

The last witness of the day was Donald Williams II, a wrestler, martial arts expert, and security professional, who was an eyewitness to Floyd’s arrest. Williams said Chauvin had Floyd pinned to the pavement in what he called a “blood choke,” which compresses arteries or veins in the neck. He yelled at Chauvin, pleading with him to remove his knee from Floyd. “You see Floyd fade away like the fish”, Williams said. “He vocalized that he can’t breathe and ‘I’m sorry.’ His eyes rolled back in his head.” In his cross-examination of Williams, defense attorney Nelson tried to suggest that the witness’s name-calling and angry shouts might have distracted Chauvin and contributed to his actions. Nelson rattled off a list of obscenities and names (“bum” was one of his favorites) that Williams yelled at Chauvin during the time his knee was on Floyd’s neck. He quoted an interview that Williams had with investigators after the incident in which he said, “I really wanted to beat the shit out of the police officers.” Nelson asked Williams, “You said that?” “Yeah, that’s what I felt,” Williams responded. “So again, sir, it’s fair to say that you grew angrier and angrier?” Williams answered, “No, you can’t paint me out as angry — I would say I was in a position where I had to be controlled. Controlled professionalism, I wasn’t angry.”

Testifying on the second day of the trial was Darnella Frazier, the teenager who shot the video that shocked the world. Frazier testified, “When I look at George Floyd I look at my dad, I look at my brothers, I look at my cousins, my uncles, because they are all Black,” said Frazier, her voice faltering. “I have a Black father, I have a Black brother, I have Black friends. I look at that and I look at how it could have been one of them.” Frazier expressed remorse that she didn’t do more. Fighting tears, and with many of the jurors looking on sympathetically, she said, “I’ve stayed up apologizing and apologizing to George Floyd for not doing more and not physically interacting and not saving his life.”

Firefighter Genevieve Hansen testifying

Jurors also heard on the second day from a Minneapolis firefighter, Genevieve Hansen, who happened upon the scene while off duty. She told jurors that she quickly realized that Floyd needed help and attempted to render aid only to be rebuffed by police. Hansen testified, “There is a man being killed, and I would have been able to provide medical attention to the best of my abilities, and this human was not provided that right.” Assistant Attorney General Matthew Frank asked Hansen, “How did it make you feel?” “Totally distressed,” she replied.

On the third day of testimony, jurors heard from 61-year-old Charles McMillian, who witnessed Floyd’s arrest and who repeatedly urged Floyd to cooperate with officers, telling him he “can’t win.” “I’m watching Mr. Floyd, I’m trying to get him to understand that when you make a mistake, once they get you in handcuffs there’s no such thing as being claustrophobic, you have to go. I’ve had interactions with officers myself and I realize once you get in the cuffs you can’t win,” McMillian said. With McMillian on the stand, prosecutors played a police body camera video of the incident. When the tape stopped, McMillian dropped his head, gasped and said, “Oh, my God.” Sobbing, he fought to continue his testimony, but eventually the judge called a recess to allow McMillian to compose himself. McMillian returned to the stand and described how he had confronted Chauvin immediately after Floyd’s was loaded into an ambulance. He said he told Chauvin he once got along fine with police, but “Today I got to look at you as a maggot.”

Floyd in Cup's Foods shortly before his arrest

Jurors also heard testimony from 19-year-old Christopher Martin, the clerk at Cup Foods who informed his manager of the suspected counterfeit bill Floyd used to buy cigarettes. Martin said Floyd was friendly, but that he appeared to be high on drugs. He also said he felt “guilty” about reporting the counterfeit $20 that led to Floyd’s death, but under company policy was required to report suspicious transactions to his manager.

Police video camera footage showing Floyd in handcuffs sitting outside Cup's Foods

Prosecutors played video footage of surveillance video showing Floyd inside the Cup’s Food store as well as video from the body cameras of all four officers at the scene. After Floyd is loaded on to the ambulance, Chauvin can be heard trying to justify his actions. Chauvin said, “We’ve gotta control this guy because he’s a sizable guy, looks like he’s probably on something.”

Day 4 of the Chauvin trial began with testimony from Floyd’s girlfriend of three years, 45-year-old Courteney Ross sobbed as she described how she met Floyd at a Salvation Army shelter in downtown Minneapolis on a visit to meet her son’s father. She was “fussing” because the boy’s father wasn’t coming. Floyd came up to her and asked, “You OK, sis?” in his “great, deep Southern voice, raspy.” They met again soon and had their first kiss in that lobby.

Floyd's girlfriend, Courteney Ross, testifies in the Chauvin trial (4/1/2021)

In a preemptive move to take away the defense’s thunder about Floyd’s drug use and addiction, prosecutors asked Ross to tell jurors about their mutual oxycodone addiction that started with prescriptions for chronic pain and led to purchasing street drugs. Ross said Floyd was using drugs at the time of his death. She also testified that Floyd was hospitalized two months earlier for several days because of a heroin overdose. (The likely source of Floyd drugs was Morries Hall, a friend of Floyd’s who was in the front seat of the car parked by the Cup’s Food store at the time of Floyd’s arrest. Hall invoked his Fifth Amendment right not to testify at the trial). On cross-examination, Ross revealed that Floyd's nickname for her was "Mama," raising the question of whether, in those minutes Floyd was under Chauvin's knee, he was calling out for his girlfriend or his dead mother.

Jurors also heard from retired supervisory Sgt. David Pleoger. Prosecutor Schleicher asked Pleoger on whether Chauvin’s force was appropriate. Ploeger replied, “When Mr. Floyd was no longer offering up any resistance to the officers, they could have ended their restraint.” Schleicher then asked if that was when Floyd was handcuffed and on the ground. “Yes,” Ploeger answered. Asked whether Chauvin initially mentioned that he applied his knee to Floyd’s neck, Pleoger said, “I don’t believe so.” On cross-examination, Eric Nelson asked Pleoger, “Would you agree with the general premise that the use of force is not necessarily attractive and sometimes officers have to do very violent things? It’s a dangerous job.” “Yes,” Pleoger replied.

Also testifying on the fourth day were the two paramedics and a fire captain who tried to resuscitate Floyd. Derek Smith, a paramedic, checked Floyd’s pulse and pupils as he lay under Chauvin’s knee. “I looked to my partner. I told him, ‘I think he’s dead.’” Smith testified that despite the lack of a pulse, they continued trying to save Floyd. “He’s a human being,” Smith said. “I was trying to give him a second chance at life.”

On Day 5 of the prosecution's case, the most senior member of the Minneapolis Police Department and head of the homicide unit, Lt. Richard Zimmerman testified that the level of force used by Chauvin on Floyd was “totally unnecessary.” Zimmerman said, “Pulling him down to the ground facedown and putting your knee on a neck for that amount of time is just uncalled for.” Zimmerman said the department’s use-of-force policy requires that prone suspects who are handcuffed must be taken off their chest as soon as possible. Asked by prosecutor Matthew Frank whether the restraint should have stopped once Floyd was handcuffed and prone on the ground, Zimmerman replied, “Absolutely.” Zimmerman added that once a suspect is handcuffed, “that person is yours. He is your responsibility. His safety is your responsibility. His well-being is your responsibility.”

Chief Medaria Arradondo testifies for the prosecution

The second week of the prosecution’s case opened with Minneapolis Police Chief Medaria Arradondo on the stand. The chief testified Chauvin used excessive force, acted inconsistent with his training and the values of the department. Arradondo said, “Once Mr. Floyd had stopped resisting — and certainly once he was in distress and trying to verbalize that — [pressure to the neck] should have stopped.” He added, “There’s an initial reasonableness of trying to just get him under control in the first few seconds, but once there was no longer any resistance, and clearly when Mr. Floyd was no longer responsive and even motionless, to continue to apply that level of force to a person proned out, handcuffed behind their back, that in no way shape or form is anything that is by policy, part of our training and is certainly not part of our ethics or values.”

Prosecutors also questioned the Hennepin County Medical Center doctor who treated Floyd and declared him dead. Dr. Bradford Wankhede Langenfeld testified that upon arrival at the hospital Floyd did not have a heartbeat “sufficient to sustain life” and that his cardiac arrest was due to a lack of oxygen. “Is there another term for that?” asked prosecutor Jerry Blackwell. “Asphyxia,” answered Langenfeld.

By Day 7, the jury was yawning and showing other signs of restlessness as the prosecution presented a parade of use-of-force trainers and experts that presented largely repetitive testimony. All the prosecution witnesses agreed on the central point that Chauvin’s long application of pressure to Floyd’s neck constituted excessive force. The defense scored some minor victories on cross-examination. For example, when Lt. Johnny Mercil, in charge of the MPD’s use-of-force training was asked to examine images that showed Chauvin’s knee on Floyd’s shoulder area. Mercil was asked by defense attorney Eric Nelson, “Does this appear to be a neck restraint?” Mercil said, “No.” Nelson also asked Mercil whether suspects under arrest “at times are making excuses,” claiming to suffer from a medical emergency by declaring “I can’t breathe” to avoid going to jail. The lieutenant agreed that happened.

Forensic experts took over on Day 8 of the state’s case. Jurors learned that George Floyd’s DNA, fentanyl and methamphetamine showed up in the forensic analysis of a white pill recovered from a second search of the squad car which Floyd temporarily occupied. BCA forensic scientist McKenzie Anderson testified the pill was found on the floor of the rear passenger seat. DNA from the pill in saliva was tested against a known sample of Floyd’s DNA. It was a match, Anderson said. Investigators also discovered two pills in the center console of Floyd’s Mercedes SUV. Breahna Giles, a chemical forensic scientist for the BCA, testified that the pills found inside Floyd’s car contained methamphetamine and fentanyl, an addictive opioid. A glass pipe from the SUV also tested positive for THC, the active substance in marijuana. The prosecution presented evidence relating to Floyd’s drug use in an attempt to “steal the thunder” from a theme that will be central to the defense case—that the real cause of Floyd’s death was drug use and a pre-existing heart condition.

Dr. Martin Tobin testifies on Day 9 of the prosecution's case

Medical testimony was the focus on Day 9 of the trial. Dr. Martin Tobin, a Chicago physician and respiratory and critical care specialist told jurors that “Mr. Floyd died from a low level of oxygen” that “caused damage to his brain that we see, and it also caused an arrhythmia that caused his heart to stop.” When the white-haired doctor with an Irish accent, who some court observers described as “right out of central casting,” used gestures to indicate specific parts of Floyd’s neck and upper anatomy, several jurors touched themselves in the same place as if to confirm the doctor’s point. Tobin showed jurors how Chauvin and Officer Kueng manipulated Floyd’s handcuffs high on his back while pinning him. “It’s like the left side is in a vise,” Tobin said, “It’s being pushed in from the street at the bottom and the way the handcuffs are manipulated [and it] totally interferes with central features of how we breathe.” As a slow-motion video was shown of Floyd’s face, Tobin described Floyd’s death: “You can see slight flickering and then it disappears, so one second he’s alive and one second he’s no longer,” Tobin said. “That’s the moment the life goes out of his body.” When prosecutor Jerry Blackwell asked Tobin if Floyd’s pre-existing health conditions had anything to do with his death, the doctor replied, “none whatsoever.”

With the prosecution’s case nearing its conclusion by Day 10, Hennepin County’s chief medical examiner, Dr. Andrew Baker, the doctor who performed Floyd's initial autopsy, testified that Floyd’s underlying heart disease contributed to his death, but he would not have died but for the pressure applied to his neck by Chauvin. Baker said, “In my opinion, the law enforcement subdual restraint and the neck compression was just more than Mr. Floyd could take by virtue of those heart conditions.” Baker described Floyd’s heart problem as “very severe” hypertensive heart disease, meaning his heart weighed more than it should. Heavy hearts require more oxygen.