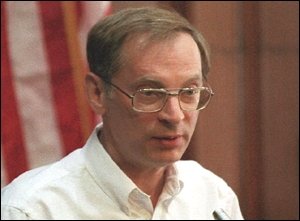

The Saturday afternoon before Christmas in 1984, on a New York City subway car making its run downtown, two black teenagers approached Bernhard Goetz. One of the teens said to the slightly built blond man, "Give me five dollars." Seconds later, Goetz fired five shots from his Smith & Wesson revolver and four young men were injured--one with a severed spinal cord. After the train came to a quick stop, Goetz jumped to the tracks below and disappeared into the darkness of the subway tunnel. City newspapers dubbed the gunman "the subway vigilante."

During the 1980s, New York City experienced unprecedented rates of crime. Murders during the decade averaged almost 2,000 a year and, in the city's increasingly dangerous subway system, thirty-eight crimes a day, on average, were reported. Citizens did not feel safe. It is not surprising, therefore, when the city's newspapers ran stories on the December 22 shooting on the IRT express, the shooter was widely praised for his actions: "Finally," many a New Yorker said, "someone has had the courage to stand up to these thugs."

THE SHOOTING AND EVENTS PRIOR TO TRIAL

Barry Allen, Troy Canty, James Ramseur and Darrell Cabey boarded the subway about 1:00 P.M. The boys, concealing screwdrivers, planned to visit a video arcade, where they hoped to steal quarters. Each of the boys, 18 or 19 years of age and high school drop-outs, all had a criminal arrest record. The other 15 to 20 passengers on the car, wary of the boisterous gang, moved toward the other end of the car. At the 14th Street station, Bernhard Goetz, age 37, entered the subway car and took a seat near the youths.

When Canty and Allen approached Goetz with their demand for five dollars, they knew nothing of Goetz's history and how the intense man, dressed in jeans and a windbreaker, would soon transform their lives. Three years earlier, Goetz had been mugged by three African-American young men and he had a permanently damaged knee to show for it. He resolved not to be a victim again and regularly carried a .38 revolver in his waistband.

When Goetz asked Canty to repeat what he just said, Canty again asked for five dollars. As Goetz later would tell investigators, "When I saw his smile and the look in his eye,... I saw they were intending to play with me like a cat plays with a mouse." He opened fire. Goetz stated that he “started spinning and pulling the trigger, trying to get as many of them as he could.” The first shot hit Troy Canty directly in the chest. The second shot hit Barry Allen in the back. The third shot traveled through the arm of James Ramseur and became lodged in his left side. The fourth bullet missed Darrell Cabey. Goetz moved towards Cabey and said (or at least thought), "You don’t look so bad, here’s another.” He fired a fifth and final shot at point blank range, severing Cabey’s spinal cord. The conductor, after bringing the subway train to a screeching halt, approached Goetz and asked, "Are you a cop?" "No," Goetz replied, "I don't know why I did it. They tried to rip me off."

The story of the subway shooter struck a chord with the frightened public, who generally proclaimed him to be a hero. Stories strongly suggested that the shooting thwarted an assault and that it would send a message to other would-be muggers. Polls showed large majorities of both white and black respondents sympathetic to the subway vigilante. Few stories emphasized that the shooter used hollow-point bullets--bullets designed to inflict maximum damage--or that two of those shot were hit in the back. One of the few public figures to criticize the shooting was New York Mayor Ed Koch who, two days after the story broke, labeled the action "animal behavior" and said "a vigilante is not a hero."

After the subway shooting, Goetz rented a car and fled to Bennington, Vermont, where he burned his jacket and dismantled his gun, scattering pieces of his weapon in the woods. On December 26, an anonymous hot line caller told the NYPD that Bernhard Goetz matched published descriptions of the gunman. Calling a neighbor, Myra Friedman, three days later, Goetz discovered that police were looking for him. He decided to end his wandering from one New England motel to another and returned to his New York apartment on West Fourteenth Street, where he gave two of his guns to Myra Friedman for safekeeping and picked up some clothes and business papers. After a drive back to New England, Goetz showed up at police headquarters in Concord, New Hampshire at 12:10 P.M. on New Year's Eve and announced that he was the subway shooter that New York police were seeking.

Concord police advised the NYPD that they had their man and then questioned Goetz for over two hours. In his rambling audiotaped interview, Goetz admitted to firing five bullets in the subway and told investigators that he used dumdum bullets because "you need maximum stopping power." After three NYPD detectives arrived in Concord, Goetz gave a second, more contentious and videotaped, confession, again making admissions that prosecutors would rely on heavily in his trial. Among other incriminating statements, Goetz told detectives that after perceiving a threat, "I decided to kill them after all, murder them all, do anything."

On January 3, with his popularity still at its peak, Goetz was brought back to New York City and arraigned on four charges of attempted murder. Later that month, a grand jury listened to Goetz's confessions and heard from a few eyewitnesses. The grand jury indicted Goetz on three charges of illegal possession of a weapon, but refused to indict on the attempted murder charges or even reckless endangerment.

Public opinion began to turn against Goetz in February with the publication of information concerning his racist views (including his use of the "n word") and the words he admitted to using before permanently paralyzing Darrell Cabey: "You seem to be doing all right; here's another." After the District Attorney's Office was granted court permission to resubmit attempted murder and assault charges to a second grand jury, additional witnesses--including two of the four victims--testified. The D.A.'s efforts paid off, and the grand jury indicted Goetz on four counts of attempted murder, four counts of assault, and one count of reckless endangerment.

Attorneys for Goetz moved to dismiss the second indictment on the grounds of prejudicial instructions on the issue of justification and perjured testimony of the two victims, Ramseur and Canty. The Criminal Term Court granted the defense motion to dismiss in January 1986, but six months later the Court of Appeals of New York reversed the lower court and reinstated all counts of the indictment. The trial was set to begin in New York City in December.

THE TRIAL

Judge Stephen Crane opened the Goetz trial on December 12, but it would be the end of April before the first witness took the stand. Jury selection took nearly four months, first a long process of "prescreening" potential jurors for bias, then two weeks of voir dire for those potential jurors who passed the first test. On April 7, 1987, the last member of the eight men, four-women jury was seated.

District Attorney Gregory Waples told jurors in his opening statement that the evidence will show that Goetz shot one of the teens "in the center of the back as he tried to flee" and that Darrell Cabey was shot and permanently paralyzed while "sitting down in a subway seat,...absolutely helpless and doing absolutely nothing to threaten or menace Bernhard Goetz." He said that Goetz's two confessions would reveal him to be a man with a "very twisted and self-righteous sense of right and wrong." He concluded by telling the jurors, "You are here to decide whether the idea of equal justice under the law for all people is a reality or is an empty dream."

Attorney Barry Slotnick followed with the opening statement for the defense. Slotnick painted his client as "neither Rambo nor a vicious predator," but rather as someone surrounded by threatening youths intent on robbing him and who, in response, took "proper and appropriate action." He warned the jury to be skeptical of evidence presented by the two testifying witnesses, Canty and Ramseur because they had a motive to lie to further their pending multi-million dollars civil suits against Goetz. He variously referred to Goetz's shooting victims as "hoodlums," "criminals," "savages," "punks," "low-lifes," and "thugs." He told jurors that the four youths "assumed the risk that a citizen like Bernhard Goetz would lawfully, justifiably, fire a weapon in protection of his property."

The State's Case

After two days of early scene-setting testimony from a paramedic, John Filangeri, who treated the shooting victims, and Detective Charles Haase, who investigated the shootings, the prosecution played for the jury Goetz's audiotaped confession made to Concord police officers. Listening through wireless headphones, the jurors heard Goetz lament, "I wish this were a dream, but it's not." He told detectives the shootings were unplanned. "If this were premeditated," he asked, "why wouldn't I have simply put on a fake mustache and worn different glasses?" He told Concord detective Christopher Domian that his prior mugging was "an education" that convinced him "the city doesn't care what happens to you" and you have to protect yourself. Goetz said the "body language" of the teens told him he was in danger and that he went into "a different state of mind." "You react," he explained, and remember that "speed is everything." He admitted going over to a seated Darrell Cabey and telling him, "You seem to be all right; here's another" as he pulled the trigger for a fifth and final time. Goetz fled after the shooting, he said, because if he stayed, "they would have wiped the floor with me."

Troy Canty, dressed in a business suit, spent more than two days on the stand describing his version of events. Under questioning from Waples, Canty admitted to heavy use of crack cocaine and convictions on several misdemeanor charges. He explained that on December 22 he and the three other youths boarded the subway with the intention of going to Manhattan to rob video games at Pace University. He testified that he was three or four feet away from Goetz when he asked him, "Mister can I have five dollars?" Goetz responded, "You can all have it!" According to Canty, Goetz then unzipped his jacket, pulled out his pistol, and began firing. "I grabbed my chest," Canty testified, "then I fell to the floor." He told jurors he heard subsequent shots, then the voice of Darrell Cabey crying, "Why did he shoot me? Why did he shoot me?"

On cross-examination, Canty admitted that he might have said "Give me five dollars" instead of "Can I have five dollars?" He denied, however, telling a reporter for the National Enquirer, "If we get caught, we plea-bargain a felony down to a misdemeanor, then walk away." He also denied telling an officer on the train, in the minutes after the shooting, "We were robbing the white guy and he shot us." Slotnick questioned Canty about prior arrests or allegations concerning robberies and threats, then questioned the witness sharply about his possible monetary interest in the outcome of Goetz's criminal case, the civil suit he had brought against the shooter for the injuries Canty suffered in 1984.

Two of the three other shooting victims were called as state's witnesses. James Ramseur, called the day after Canty finished his testimony, refused to take the stand despite having received immunity from prosecution. When a court officer reached out with a Bible, Ramseur pushed it away. Ordered by Judge Crane to take the oath, Ramseur, hands in pockets, stated, "I refuse." The judge cited Ramseur for contempt and he was led out of the courtroom. Barry Allen, who had not been granted immunity from prosecution, asserted his Fifth Amendment right not to incriminate himself in response to nearly every question from both Waples and Slotnick. Despite the constant invocations of the the Fifth Amendment privilege, Slotnick persisted in asking Allen question after question for over twenty minutes--in an apparent attempt to impress the jury with what he hoped they would see as Allen's unreasonable intransigence.

Amanda Gilbert attended to the injured young men after the shooting. She testified for the state that one of the injured youths told her, "Miss, I've been shot through the heart and I'm dying." Gilbert assured him otherwise. She testified that Darrell Cabey, leaning over in his seat told her, "I didn't do anything. He shot me for nothing." (After argument by attorneys, the judge ruled the statements by the shooting victims to be inadmissible hearsay and told the jury not to consider the statements in their deliberations.)

The prosecution called numerous eyewitnesses to the shooting--nine in all--to testify in the Goetz trial. Victor Flores told jurors he noticed "a group of kids" about fifteen feet away from his seat on the subway car. After the first shot rang out, he saw Goetz, in rapid succession, "shooting the kids in front of him." He saw two of the youths fall to the floor and a third slump into a seat. Goetz, he said, "looked like he was very mad" at the time of the shooting, but afterwards "seemed like he was worried." Flores testified that he did not hear Goetz address Cabey or any of the other shooting victims. Armando Soler, the conductor, described the scene after the shooting as "mass confusion: everybody was running for cover." Goetz, however, "was just sitting there, very calm." "I asked [Goetz] if he was a police officer," Soler testified, "and he said no." Solitaire MacFoy testified that he witnessed Goetz take out his gun and, with "a calm and bland" and "somewhat calculating" expression, began firing very deliberately at each of the young men around him.

Oftentimes, the state's eyewitnesses hurt as much as helped the government's case. Loren Michaels, a credit manager for a trading company, testified that before the shooting the young men "seemed to be kind of laughing and moving around on the seats." On cross-examination, Michaels admitted that in his grand jury appearance he had characterized their activity as "a bit noisy and rude" and that he had considered at the time the possibility that the teenagers might be about to create some sort of disturbance. Garth Reid was holding his child in a subway train seat when the shooting began. He testified that he did not see any of the youths display any weapons or make any threatening gestures to Goetz before the bullets starting flying. On cross-examination, when Slotnick asked whether, before the shooting, someone said, 'Look at those four punks bothering that man?', the prosecution objected on the ground of hearsay and a heated discussion between attorneys ensued at the bench. After Judge Crane overruled the objection, Reid conceded that he had heard the statement made about the four trouble-making "punks" before Goetz drew his gun. (Later, when Garth's wife, Andrea Reid, testified, it was revealed that the comment about the four "punks" came from her.) Mary Gant, an actress and the next eyewitness, told jurors that she never saw Canty "make any kind of menacing gesture" or raise his voice. On cross, however, Gant conceded that the behavior of the youths made her anxious: "I was concerned. I was afraid." Another eyewitness, Josephine Holt, also aided the defense by admitting on cross-examination that she had described, in her grand jury testimony, the youths as "standing around the white man" and acting in a loud, harassing, and menacing manner.

Many trial observers believed that the prosecution's star eyewitness was Christopher Boucher, the one witness who testified that he saw Goetz shoot Darrell Cabey as he sat helplessly in a seat by the conductor's cab. The testimony was damning:

Boucher: [Cabey was] sitting back with his hands like grasping the bench and a frightened look on his face...[Goetz's] hand was already up with the gun....He was standing, holding his gun pointed at the individual and in just a matter of seconds he fired...

Waples: And what did the person who was sitting down do at the moment the shot was fired?

Boucher: Well, he was sitting, grasping the bench, and he just tightened.

Waples: Did you ever see that person try to get out of that seat?

Boucher: No.

Waples: Did you ever see him threatening Mr. Goetz?

Boucher: No.

Waples: Did he have anything in his hand that you saw?

Boucher: No....

Waples: Is there any doubt in your mind that you saw a person sitting in that seat when the shot was fired?

Boucher: No, no doubt.

Waples: And how is your eyesight?

Boucher: It's perfect.

The prosecution followed up Boucher's dramatic testimony with a showing of the videotape of the interview of Goetz by New York City police officers in Concord. With the lights dimmed, jurors watched the tense confrontation between suspect and detectives on a 27-inch Sony monitor set in front of the jury box. Goetz bristled with hostility toward Detective Susan Braver, complaining about her voice, the way she framed questions, her attitude, and the city that employed her. At one point in his confession, Goetz lectured Braver: "Do you know how sick your legal system makes me Miss?...New York city is a system that knows so much and is so good you decide what you decide what is right and wrong....This city doesn’t care about lawlessness. You talk about anarchy that’s what there is now....What I did down there was, let’s say it’s wrong, that doesn’t bother me, but what this did is it showed the system as being a sham." In the video Goetz compared his actions on the subway to that of a trapped rat: "What you have here is nothing more than a vicious rat. That’s all it is is. It’s not Clint Eastwood." Mark Lesly, one of the Goetz trial jurors, later wrote that the videotaped confession provided "our only glimpse of the dangerous nature of Goetz's wrath." Otherwise, Lesly said, jurors could never have imagined "the meek-looking, mild-mannered individual sitting across from us in the courtroom had been capable of committing the violent acts that he did."

District Attorney Waples probably should have ended the state's case with the videotape. Instead, James Ramseur was recalled to the stand--and ended up causing serious damage to the prosecution case. After offering his version of events in his direct testimony, Ramseur blew up under the relentless and hard-hitting cross-examination of Barry Slotnick, who seemed much more interested in Ramseur's criminal past than anything that happened on the subway. Slotnick also suggested through his questions that Ramseur was shaping his testimony to help convict Goetz in the hopes that a conviction would improve prospects for the civil suit he and others had filed against Goetz. Ramseur discounted this idea (presciently), "He’s gonna be found not guilty anyway. I know what time it is." As questions continued, the exchanges became more and more heated, with Ramseur accusing Slotnick of "twisting" his words and arguing that certain questions were "none of your business." Eventually, Ramseur pleaded "Take me out of here!" and refused even the direct order of Judge Crane to answer a question ("I refuse."). He was held in contempt and his testimony stricken from the record. At Ramseur's sentencing for contempt, Judge Crane admonished him for behavior which, he said, "conveyed viciousness and selfishness more eloquently than words could." Slotnick, the judge said, "owes you a vote of thanks."

The Defense Case

The defense, in an attempt to get jurors to understand Goetz's reaction in the subway, opened its case by presenting evidence concerning the injuries Goetz had sustained in a mugging in January 1981. Charles Cozza testified that he came to Goetz's aid after he saw him being "repeatedly punched and kicked" by an assailant. Dr. Murray Burton told jurors that the assault had left Goetz with a permanently damaged right knee.

Officer Peter Smith was called to support the defense contention that Goetz's shooting victims were a gang of thugs intent on robbing him. Smith, one of the first members of NYPD to arrive on the scene, testified that Troy Canty--still lying on the floor of the subway car--told him, "we were going to rob him but he shot us first." The prosecution, however, produced a videotaped interview Smith had with a television reporter on the day of the subway shooting. In the interview, Smith said, "[Canty] said they were just fooling around with the guy." On cross-examination, Smith said he was "nervous" during the television interview and stood by his statement in court the previous day.

Dr. Bernard Yudwitz, a neuropsychiatrist, testified in support of the defense's theory that the five shots fired by Goetz were all part of a single "adrenaline response." Yudwitz suggested that with the very first shot, Goetz went on "automatic pilot" and had no real opportunity to re-evaluate the situation until the last bullet had been fired. Obviously, Yudwitz (who had never examined Goetz) was critical to the defense's attempt to explain the final, most troubling, shot that paralyzed Cabey and which, according to Goetz's own statement, came only after he approached Cabey and said, "You don't look so bad; here's another." On cross-examination, Waples got from Yudwitz a concession that the "automatic pilot" response is not universal, and that each person's response to a stressful situation can be different. Juror Mark Lesly later described Yudwitz's testimony as "an important consideration in our deliberations about whether Goetz's actions could be legally justified."

On May 29, the jury took a field trip. They visited a New York City subway car that was essentially identical to the one in which the shooting took place. Judge Crane instructed that no one address the jurors during their inspection of the car, so jurors were left to their own imaginings and role playing. Mark Lesly said the visit impressed on him how Goetz "had no real room to escape" and how, while he fired at Canty, "he was extremely vulnerable to an attack if Cabey or Ramseur tried to jump him." He called the field trip "very valuable" and said that it won "some crucial points for the defense."

Ballistics expert Joseph Quirk re-created a scenario for the subway shooting that he said was consistent with the ballistics evidence. For his courtroom demonstration, Quirk employed four roughly dressed African-American youths, all members of the Guardian Angels group, to stand in for the four youths shot by Goetz. Probably quite intentionally, the defense's demonstration helped drive home to jurors how threatening the developments on the subway might have appeared to Goetz. The identified purpose, however, was to demonstrate possible bullet paths in relation to each injured youths. Quirk testified that he believed Allen was shot ducking down rather than (as the prosecution suggested) running away and that Cabey was shot standing up by the fourth bullet, and then fell backward into the subway seat. The fifth bullet, Quirk contended, probably missed all of the victims and instead hit the subway car's steel panel directly. If Quirk's interpretation of the ballistics evidence was correct, Goetz did not approach Cabey after his fourth shot and make his incriminating statement before firing a final, paralyzing bullet. On cross-examination, Quirk admitted that the prosecution's theory of the firing pattern was also consistent with the ballistics evidence, but insisted that his own interpretation was "more likely." He also admitted to receiving $1500 from the defense team for his expert testimony. Quirk also conceded, after the prosecution produced a photo showing a bullet entry wound in Barry Allen's back, that he had based his conclusion about the position of Allen on incorrect information provided him by the defense.

Following Quirk, Dr. Dominick DiMaio, a former medical examiner, testified that he believed the bullet wounds of the four youths largely supported the defense's theory of the shooting--a theory Waples called "preposterous." DiMaio contended that Cabey's wound suggested he was shot standing rather than sitting, because otherwise the trajectory of the bullet indicated Goetz would have had to have been almost "on his knees to inflict the wound." On cross-examination, DiMaio admitted that while serving as New York City medical officer in 1976 his office concluded that six women had died of natural causes when in fact, it later was discovered, each had been smothered by a serial killer.

Closing Arguments, Deliberations, and Verdict

The prosecution's rebuttal witnesses included two medical experts who strongly challenged the defense's theory of the shooting as presented by Quirk and DiMaio, and then it was time for summations. Barry Slotnick argued that the prosecution had failed to prove "in any manner, form, or shape whatsoever that Darrell Cabey was shot while sitting down." He contended that the evidence showed that the five bullets came in rapid succession and argued that Goetz, in the words of Dr. Yudwitz, had gone on "automatic pilot." He described the shooting victims as "a gang of four" and told jurors that when they prey on people they "take a chance...that it may backfire on them." When Goetz told detectives what he said to Cabey he was, according to Slotnick, "fantasizing." Slotnick called Goetz's memory of the "here's another" statement unreliable, coming as it did in Goetz's "post-traumatic" period. Slotnick ended his four-hour summation by telling jurors, "They came in without a case; let them walk out without a conviction."

The next morning, Gregory Waples addressed the twelve jurors. Waples began by saying that the law protects "the worst man" the same as the best--and that "this case presents a monumental challenge to this most precious tenet of a free and democratic society." Waples argued Goetz, "by his own admission, did everything within his power to murder four young men in the subway system." He called the case "sad" and "confusing," but asked jurors to base their verdict "solely on the law and the evidence" rather than "capitulate to the fear of crime." "Troy Canty, Barry Allen, James Ramseur, and Darrell Cabey are not on trial in this case," Waples noted. What is on trial, he said, is "a question of civilization." Waples asked the jurors to consider especially the shooting of Cabey: there can be no excuse, he said, "for the totally needless injury that the defendant inflicted on Darrell Cabey." Any attempt to justify that shooting, the prosecutor contended, is "a cruel joke." He argued that "no reasonable person could have fired that shot." Believe Goetz's own words, Waples told the jurors. The account of the shooting by "this strange and troubled man" was not some fantasy, it included vivid detail showing the defendant had his full cognitive powers at the time and "lived each split second." Waples ended his lengthy summation by telling jurors that if they choose to acquit Goetz on the major charges "I will be disappointed, but the cause of justice will suffer more."

Jury deliberations began on the afternoon of June 12, 1987. The jury quickly voted to find Goetz guilty on the charge of illegally possessing a loaded firearm outside of his home or business--it was impossible to deny that Goetz had a loaded gun on the subway, and it he was not licensed to carry one. From that point on, though, deliberations tipped the defendant's way. Jurors voted to acquit Goetz on the four attempted murder charges on the theory that, while he wanted to end the real or imagined threat posed by the teenagers, he lacked the motivation to kill them. In the words of one juror, Goetz might have been reasonable or unreasonable in his feeling that he was trapped, "but he didn't go out hunting." The most difficult deliberations concerned charge 11, assault in the first degree against Darrell Cabey. The fifth bullet fired by Goetz, the one that paralyzed (a most likely seated) Darrell Cabey, was hard to excuse. The jury debated whether Goetz had time to conclude that whatever threat the youths presented were effectively ended by the time he went over to Cabey and, according to his own confession, said, "You seem to be doing all right; here's another," before firing his final shot. Some jurors noted that Goetz's account contradicted several other witnesses who described the shots as coming in rapid succession. The "rapid succession" theory allowed jurors to accept the defense argument that Goetz effectively went on "automatic pilot" after he fired the first shot; the five shots were all really one event. Jurors speculated that Goetz might not in fact have said "here's another," but just had that thought in his mind, and possibly only after the shooting. One witness, however, presented problems for the defense: Christopher Boucher. Boucher testified that Goetz did pause between his fourth and fifth shot, and went over to Cabey and fired the last shot point blank into Cabey's side as he sat in a subway seat. The fact that the evidence concerning the location of Cabey's entry wound was inconsistent with Boucher's testimony allowed some jurors to speculate that Boucher made his whole story up, though for what possible reason the jurors had a hard time determining. In the end, the concept of reasonable doubt turned the jury to a not guilty vote. On the afternoon of June 16, the jury announced its verdict. With the announcement of the "not guilty" verdict on the Cabey count, spectators gasped. With the jury foreman James Hurley's final "not guilty," Bernhard Goetz smiled.

Judge Crane sentenced Goetz to a six month jail term, five years probation, a $5000 fine, 200 hours of community service, and an order that he seek psychiatric help. On appeal, his sentence was changed to one year, with no probation. He served eight months. In 1996, a New York jury awarded Darrell Cabey $43 million in a civil suit he had brought against Goetz for his injuries.

Goetz ran for mayor of New York City in 2001 and the position of Public Advocate in 2005, but lost badly in both contests. He campaigned for offering vegetarian dishes in public schools and worked tirelessly for the cause of squirrel rescue. (Goetz installs squirrel houses, feeds squirrels, and applies first aid to injured squirrels.) He appeared in the 2002 film Every Move You Make, playing a criminalist who instructed a female stalking victim on how to carry a concealed weapon.

The Goetz case stands as a monument to a particular time in our cultural history, a time during which tension over issues of race and crime was spiking. It was a difficult case; justice is sometimes hard to define.

In a 2004 interview, CNN's Nancy Grace asked Goetz, "Do you ever wish you had just given them $5?" Goetz replied, "I think it would have been the better thing for me, in my life, if I had just given them all my money, even though they might have pushed me around and beat me up for a second." But Goetz then added, "But I think it was good for New York City. What happened was very good for New York City because it forced them to address crime."