America was not always the “Land of Liberty.” In the 1630s, in the Massachusetts Bay Colony, questioning Puritan dogma could bring you a world of trouble. It could get you shunned, it could get you ex-communicated, it could even get you criminally convicted and banished. Anne Hutchinson found all this out in 1637. But Hutchinson’s trial and conviction also, in ways that would have surprised her detractors, helped set American on a path towards greater toleration for religious differences.

Background

Hutchinson’s story, like so many of the Colonial Era, begins in England. In the late 1620s, John Winthrop, who, as the Governor of the Colony would later decide to prosecute Hutchinson, grew disenchanted with what he saw as the “papist” (Catholic) leanings of the Church under King Charles I. He also was unhappy with what he and other Puritans believed was a moral decline in his country. (The word “Puritan” is derived from the goal of the sect to “purify” the church of its Catholic excesses and tendencies and return to a church more like one that early Christians might have recognized.) The final straw for Winthrop and a band of Puritans was decision of King Charles to abrogate Parliament in 1629 rather to accede to Parliament’s demands that Charles pull back from what Puritans saw as his movement toward “popery.”

When Winthrop and other Puritan landholders asked to leave England and establish a new colony in America based on Puritan principles, King Charles saw it as a good riddance and granted the colonial charter. Winthrop and nearly one thousand other Puritans set sail across the Atlantic in eleven ships in the spring of 1630.

Anne Hutchinson was the daughter of Francis Marbury, a member of the clergy who himself had been tried and convicted of heresy in 1578 in London. Anne was born in 1591 and grew up in the town of Alford, population less than 500, near the central east coast of England. With her father under house arrest for again attacking the Church of England, Ann could enjoy, in her early years, his tutoring, including readings from the transcript of his own heresy trial.

Francis Marbury finally promised to cease his criticism of his superiors and regained his license to preach. Francis accepted a post as vicar in London when Anne was 14, and the family followed him there. Six years later, Francis Marbury died suddenly, but not before he had given Anne not only a strong Christian faith, but also a healthy contempt for the Anglican Church.

At age 21, Anne Marbury married William Hutchinson, five years her senior. The couple moved in to a home in Alford. One Sunday they traveled to the Church of St. Botolph’s, some 24 miles from Alford, to hear a sermon delivered by the minister John Cotton, who was rapidly gaining a reputation as a gifted speaker. They would make the six-hour trip many times more. Cotton preached that God offers salvation to the elect without condition—that neither faith nor good works was required. “Absolute grace,” he called it, and Anne saw Cotton’s view as absolute truth.

With the ascension of Prince Charles to the throne in 1625, England began to shift back toward Rome and away from Calvinism and Puritanism. All books on the subject of religion required a license from the Anglican Church and sermons departing from orthodox teaching were banned. In this increasingly hostile environment, Puritans faced a choice—they could go underground, they could go to prison, or they could go to America, where they might hope to continue preaching as they saw fit openly.

John Winthrop

In April of 1630, the Massachusetts Bay Company, led by John Winthrop, boarded a fleet of ships near the Isle of Wright.

The first year in the New World was hard. Two hundred settlers died of cold, illness, or starvation. When the first supply ship arrived, 80 settlers took the return trip back to England.

Three years later, John Cotton left hiding in the Puritan underground and sailed for Massachusetts. He soon became the most popular preacher in the new colony. His Sunday sermons, running up to six or seven hours in length, were copied by church-goers and discussed at length.

Cotton’s departure for America left Hutchinson without her most important religious inspiration. She said that after Cotton and another minister she admired left, “there was none in England that I durst hear.” She experienced a revelation that she should follow Cotton to the New World. She should “go thither also” even though “there I should be persecuted and suffer much trouble.” William sold his business and bought the family, including ten children, tickets (at 100 pounds per person) for the trip to America.

Anne Hutchinson arrived in Boston harbor in September of 1634. John Cotton greeted her on the pier and led the Hutchinson family up the dock to their new home. Upon their arrival, Massachusetts Bay Colony had about 5,000 English settlers, with about 1,000 of those living in Boston, the colony’s largest town.

Six weeks later Anne was accepted for full membership in the Boston church. Religion was everything in a Puritan community. The Bible was often the only book in a home. Scripture was read and studied on a daily basis. Church services were long and frequent. Events that today would be explained by science, luck, or coincidence were explained in Biblical terms. Historian Frank Collinson described the life of a Puritan as “in one sense a continuous act of worship.”

Services were held in spare meetinghouses without altars or statuary. There was no singing or formal liturgy. No Christmas or wedding celebrations, no carnivals or sacred places. It was all rather severe.

In the Massachusetts Bay Colony, women, banned from participation in church services, often met in their homes to discuss their minister’s last sermon or Biblical text. It was all that was left them. Women could not be ministers, could not vote on church matters, and could not even talk in church. They entered the church meetinghouse through a separate door and sat together on a separate side of the building.

It was in these women’s religious study groups held in private homes that Anne Hutchinson first began in 1635 to make a name for herself as an astute interpreter of the Bible. Her meetings grew in popularity. She added a second weekly session to accommodate all the women who wanted to hear her wisdom. Anne’s influence came from not only her Biblical training and intelligence, but also because of the high social status of her family in the colony. Will Hutchinson, Anne’s husband was wealthy. They lived in an impressive gabled home just across from Governor Winthrop’s house in Boston.

Hutchinson began to raise eyebrows in the colony when word leaked that in her study groups she had questioned the Biblical interpretations of local ministers in their sermons. In particular, Anne took issue with ministers who suggested that people need to display their faith, perform good deeds, and act as a decent Puritan should in order to show that they have been saved. Anne rejected this view, which was called a “covenant of works.” Instead, she insisted that the Bible makes clear that salvation is a matter of grace—that God chose souls before birth and granted the gift of salvation without conditions. This was called “a covenant of grace.” A covenant of works versus a covenant of grace: that theological question would take center stage in the trial of Anne Hutchinson.

The Apostle Paul, as noted by Anne and others, seemed to side with the covenant of grace in Ephesians 2:8-9: “For it is by grace you have been saved, through faith—and this is not from yourselves, it is the gift of God—not by works, so that no one can boast.” Luther and Calvin, key figures in the Reformation, also accepted salvation as a matter of grace. The Puritan ministers undoubtedly saw a problem with the suggestion that people could sit idly by and expect salvation—it was all too easy and might discourage rule-following and even, God forbid, skipping church services. Winthrop saw the Hutchinson view as “a very easy and acceptable way to heaven—to see nothing, to have nothing, but wait for Christ to do all.”

The crisis deepened in 1636 when Hutchinson, upset with a sermon being delivered by John Wilson, a minister hand-picked by Governor Winthrop to replace a minister favored by Anne, stood up and walked out of the meetinghouse. A number of other women followed her out. A colleague of the minister complained of Hutchinson and her supporters, “Now the faithful ministers of Christ must have dung cast on their faces.”

For Hutchinson, things turned toward the better. Her political supporter, Henry Vane, was elected governor, replacing John Winthrop. And she soon found a new minister who shared her theological views. John Wheelwright arrived from England in May 1636, and began preaching in Boston the next month. Winthrop was left to stew, writing in his diary about Hutchinson’s “dangerous errors.” But the schism over the question of salvation and whether it came unconditionally from God or had to be earned through works continued to deepen.

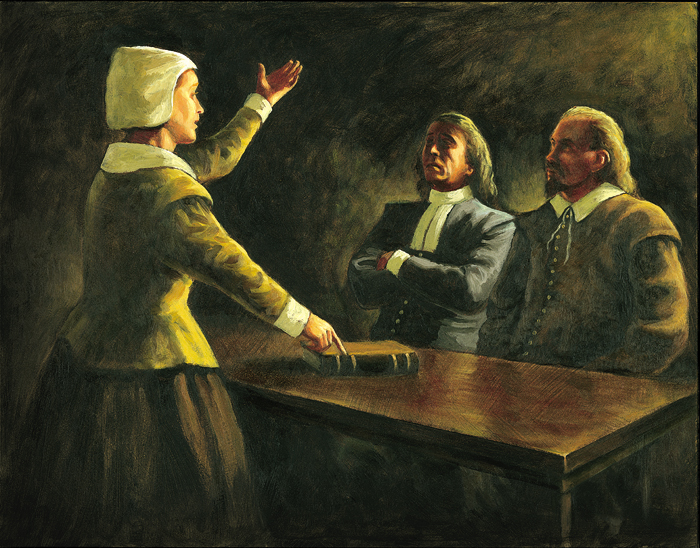

Anne Hutchinson was called to a meeting in December 1636. She faced a panel of seven ministers who demanded to know her views on the Scripture and on their own preaching. Two and a half months later, ministers meeting in Cambridge for a Synod identified 82 errors held by Hutchinson that had been recorded in their meeting with her. They also banned her from leading religious discussion groups, which they called inappropriately “prophetical” and “disorderly.” Governor Winthrop offered a summary of her grave mistakes: She would “interpret passages at her pleasure and expound dark places of Scripture and make it her own.” Rather that sticking to “wholesome truths,” she “set forth her own stuff.”

Winthrop succeeded in dispatching Reverend Wheelwright to Mount Wollaston, where he could cause less harm. May 17, 1637 was a turning point in the history of Massachusetts Bay. Magistrates and freemen assembled in Cambridge Common to decide who would control the colony. Supporters of John Winthrop and his orthodox theology carried the day. Winthrop was elected Governor for a second time, replacing Henry Vane, who had been strongly backed by the Hutchinson.

The Great and General Court of Massachusetts rotated its sessions between Boston and Cambridge (or Newtown, as Cambridge was called at the time). When Winthrop decided to put Hutchinson on trial, he determined that his prospects for conviction were better in Cambridge than in Boston. The residents of Cambridge tended to be landed gentry and more conservative than the residents of Boston, who held more mercantile interests.

The Trial

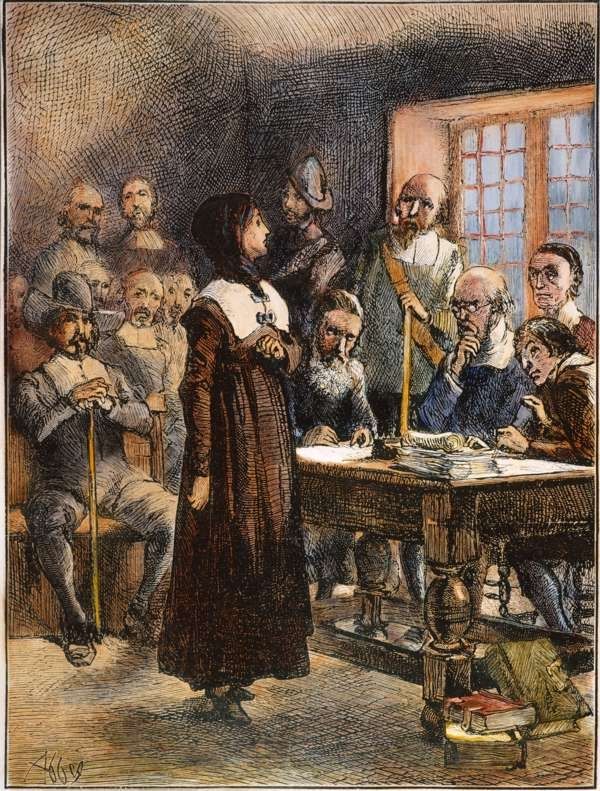

The trial of Anne Hutchinson began on November 7, 1637 in a thatched-roof meetinghouse in Cambridge. Wearing a black wool cloak, a white bonnet over her long hair, and a white linen smock, Hutchinson entered the room and a voice announced, “Anne Hutchinson is present.” The nine magistrates and thirty-one deputies of the General Court of Massachusetts, including the governor, deputy governor, a team of assistants, and freemen selected by the 14 towns of the colony, took their seats on backless wooden benches that faced the crowd. The forty men included two recently appointed replacements for judges who expressed sympathy for Hutchinson’s case. Eight ministers also strode into court, all on hand to offer their testimony.

The General Court, whose authority derived from the royal charter, was an all-powerful body in the colony. It mixed legislative, executive, and judicial functions. It legislated on all aspects of colonial life, from the color of clothes that could be worn to requiring attendance at Sunday services. The only check on its power was the knowledge of its members that rulings that appeared too arbitrary or self-serving could prompt calls for a revocation of the charter.

Governor Winthrop, both the chief prosecutor and the chief judge, hoped that the trial would fortify his position of power and unify the colony, which had become divided and weakened by fighting over religious issues, especially the question of salvation. Winthrop, sitting at a desk, banged his gavel and called out, “Mistress Hutchinson, Mistress Hutchinson.” When the crowd quieted, he continued: “Mistress Hutchinson, you are called here as one of those that have troubled the peace of the commonwealth and the churches here.” Standing silently before the Governor, Hutchinson listened as the Governor outlined what he saw as her sins. “You have spoken diverse things…prejudicial to the honor of the churches and ministers….And you have maintained a meeting or general assembly in your house that hath been condemned by the general assembly as a thing not tolerable or comely in the sight of your God nor fitting for your sex.” Winthrop ended his opening remarks with a threat: “If you are obstinate in your course, then the court may take such course that you may trouble us no further.”

Hutchinson answered by complaining about the vague nature of the accusations against her: “I am called here to answer before you, but I hear no things laid to my charge.” Winthrop replied, “I have told you some already, and more I can tell you.” “Name one, sir,” Anne demanded. “Have I not named one already?” was Winthrop’s somewhat lame reply. Nothing Winthrop had alleged Hutchinson had done amounted to a criminal offence. “We are your judges and not you ours,” Winthrop reminded Hutchinson. “If you have a rule for it from God’s word, you may,” Anne countered.

Hutchinson and Winthrop proceeded to trade Biblical passages, either as evidence for or against the right of a woman to provide instruction on the meaning of Scripture. Anne pointed to Titus which says older women are the teachers of “honest things,” while Hutchinson noted that Timothy 2:12 states, “I permit not a woman to teach,…but to be in silence.” Arguments in Puritan Massachusetts were won or lost on Scripture—every word was considered meaningful and true.

“Do you think it not lawful of me to teach men and why do you call on me to teach the court?” Anne asked the Governor. Winthrop responded, angrily, “We do not call upon you to teach the court, but to lay yourself open.”

The governor conceded Hutchinson was a woman of unusual talents: “Yes, you are a woman of most note, and of best abilities.” But that made her all the more dangerous. She had influence over the opinions of others and, Winthrop insisted, “You show not in all this by what authority you take upon yourself to be such a public instructor.”

Then, suddenly, Anne seemed ready to collapse. A chair was called for, and the trial continued.

Magistrate Thomas Dudley launched into an attack on Hutchinson, claiming that “Mistress Hutchinson has depraved all the ministers and hath been the cause of what is fallen out.” The charge suggested that Hutchinson had acted seditiously and in breach of the peace—charges which, if proven, might lead to her banishment. Anne rose to say, “I pray, sir, prove it.” Dudley and Hutchinson debated whether Anne had accused ministers of preaching falsely a covenant of works. “When they do preach a covenant of works, do they preach the truth?” Dudley asked. “Yes sir,” Anne replied, “but when they preach a covenant of works for salvation, that is not the truth.” Dudley persisted, telling Anne that she not only did say ministers preached a covenant of works, but asserted that they “were not able ministers of the New Testament.” Anne argued that what she believed or said in private could not be a crime, and as women had no public role in Puritan society, what opinions she had or expressed could only be considered private—a rather clever argument.

Winthrop looked to the ministers in court, hoping they might have something to say that would add meat to the charges against Hutchinson. None took the bait. “Our brethren are very unwilling to answer, unless the court command us to speak,” said the Reverend Hugh Peter of Salem. Winthrop issued the command and six ministers testified. After they were done, Dudley offered a summary: “You see they have proved this, and yet you deny this, but it is clear. You say they preached a covenant of works and are not able ministers.” Winthrop added, “Here are six undeniable ministers who say [what you deny] it is true.” It had been a long day in the windowless meetinghouse. Winthrop announced, “The time now grows late. We shall therefore give you a little more time to consider of it, and therefore desire that you attend the court again in the morning.”

Hutchinson believed that one of the ministers had made a number of false statements about her private conference with the colony’s ministers the previous winter. When court reconvened, Anne asked that all the witnesses of the day before be recalled and swear to an oath that there testimony was true. The ministers expressed reluctance, being of the belief that taking an oath amounted to an affirmation of the absolute truth of everything they said—and their confidence about their testimony was less than absolute. Winthrop declared. “I see no necessity of an oath in this thing”—to which the Hutchinson supporters in the crowd shouted out, “We are not satisfied!” But Winthrop would not budge.

Asked for the names of defense witnesses, Hutchinson offered three. John Coggeshall told the court that Hutchinson “did not say all that [the ministers] lay against her.” Thomas Leverett, a lawyer, said that Anne had not specifically charged the ministers with preaching a covenant of works, only that “they did not preach a covenant of grace so clearly as Mr. Cotton did.” Hutchinson’s third and most influential witness, John Cotton, took a seat next to Anne.

Without question, the opinions of John Cotton mattered. Hutchinson biographer Eve LaPlante writes in her book American Jezebel that Cotton was “the unmitred pope of a pope-hating commonwealth.” Cotton testified reluctantly, telling the court, “I did not think I should be called to bear witness in this cause, and therefore did not labor to call to remembrance what was done.” Cotton told the court “that I was very sorry that she put comparisons between my ministry” and that of the other ministers. But Cotton added, to Anne’s relief, that he never heard her specifically accuse other ministers of preaching a covenant of works. And if Anne had left things there, she might have gotten off with an admonishment, not a conviction for heresy. But she couldn’t stop herself. She began to lecture the court.

Hutchinson told the court that the Lord told her she “must come to New England, yet I must not fear or be dismayed.” She said “the Lord did give me to see that those who did not teach the New Covenant had the spirit of the Antichrist.” She told the judges that she saw the truth “by an immediate revelation” from God—“by the voice of his own spirit to my soul.” To her judges, this was arrogance and heresy. God spoke only through ministers and Scripture, not directly to a woman. Deputy Governor Dudley announced, “I am now fully persuaded that Mrs. Hutchinson is deluded by the Devil.”

Anne was not done. She ended her lecture with a warning: “I know that for this you go about to do to me, God will ruin you and you’re your posterity and the whole state!” Historian David Hall writes that Anne’s “outburst made it easy” for the judges to do what they wanted to do anyway—rid the colony of Anne Hutchinson. In his private record of the proceedings, Winthrop called Hutchinson’s performance “the impudent boldness of a proud dame.”

When Anne finished speaking, Governor Winthrop pointed at Hutchinson and said, “This had been the ground of all these tumults and troubles. This had been the thing that has been the root of all the mischief.” Most of the judges, at least thirty of them, shouted their agreement: “We all consent with you!” Winthrop declared Hutchinson guilty. Of what, exactly, the court was less than clear. The finding seems to rest both on the heresy of claiming a revelation and sedition, in resisting the lawful authority of ministers. “The court hath declared itself,” he announced, and said it “would now consider what is to be done with her.”

Winthrop summed up the proceedings and asked for a vote. “If it be the mind of the court that she shall be banished out of liberties and imprisoned till she be sent away, let them hold up their hands.” Only two of the forty judges voted against banishment and imprisonment—and John Cotton was not among them. One minister abstained. Winthrop pronounced sentence: “Mrs. Hutchinson, the sentence of the court you hear is that you are banished from out of our jurisdiction as being a woman not fit for our society, and are to be imprisoned till the court shall send you away.” Anne demanded to know “wherefore I am banished.” But she got no answer from Winthrop: “Say no more, the court knows wherefore and is satisfied.”

Epilogue

A week after the sentencing, the General Court reconsidered its decision to erect a new college in Boston, and voted instead to build it in Cambridge because “this town was kept spotless from the contagion of opinions” that infected other parts of the colony. The new college would be named after “Mr. Harvard, who died worth 1600 pounds” and gave “half of his estate to the erecting of the school.”

The General Court had sympathy enough for Hutchinson to allow her to remain in Massachusetts through the winter. She stayed, under house arrest, at a home in Roxbury. She took with her only clothes, a Bible, and a guide to medicinal plants.

Where to go? In March 1638, William Hutchinson and 17 other men seeking a new, more religiously tolerant place, met in Boston. They incorporated themselves into what they called a “Bodie Politik.” And they all signed their names to what came to be called “the Portsmouth Compact.” The stated object of the Compact was to found a state where all “might worship God according to the dictates of conscience…unawed by civil power.”

William Hutchinson and six other Compact signers headed south. After meeting with Roger Williams and local Indians, the group settled on a new home: Aquidneck Island, south of Roger Williams’s Providence Plantations. Some years later, the new settlement of Portsmouth would become part of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations. The influence of both Williams and Hutchinson is evident in the 1663 charter for the new colony—a place where all might worship God according to the dictates of their own conscience. Or as the charter puts it: “No person …shall in any wise be molested, punished, disquieted or called into question on matters of religion—so long as he keeps the peace.”

But to return to Anne’s story. Before she could leave Massachusetts,

Meanwhile, Anne Hutchinson remained under arrest in Massachusetts, under orders to leave the colony before the end of March 1638. Before she would leave Massachusetts, however, she faced a church trial. Before the congregation of the Church of Boston, Anne was examined and excommunicated. In the proceeding, John Cotton used over-the-top language to describe the damage he believed Anne had caused in the colony: “And so your opinions fret like a gangrene and spread like a leprosy, and infect far and near, and will eat out the bowels of religion and hath so infected the churches that God knows when they will be cured!” Reverend John Wilson declared that Hutchinson had been “raised up by Satan…to cause divisions and to take away hearts and affections one from another.” By now, Hutchinson had become a community scapegoat. The proceeding ended with Wilson announcing, “I do deliver you up to Satan, that you may learn no more to blaspheme, to seduce, and to lie!”

On April 1, 1638, Anne Hutchinson began a six-day walk south to John Williams’s Providence Plantation, where she boarded a ship that took her to the island of Aquidneck. In Rhode Island, Anne could speak freely, and she could again enjoy the company of her husband, children, and grandchildren. But her husband Will, the first governor of Rhode Island, died in 1642 at the age of 55. That summer, Anne decided to leave Rhode Island and travel west to settle on land in Pellham Bay in the Dutch settlement of New Amsterdam (which would later become New York). In July 1643, Anne was warned by Dutch neighbors that Siwanoy warriors were on their way and that she and her family should flee their farmstead. But Anne put her trust in God. The warriors swept into Pellham Bay. They scalped Anne and six of her children, then burned down her house.

What to make of the trial of Anne Hutchinson? First, the trial gave Anne the chance to address not only her entire colony, but posterity—an opportunity few women in the 1600s could ever hope to enjoy. Second, and perhaps more importantly, the trial led to a decision of the General Court in November 1637 might well have been wrong, but it helped lead to the birth of a nation where liberty would take on a new and more generous meaning. While the decision ended religious freedom for those in Massachusetts whose views differed from the approved theology, it led to an exodus of dissenters who helped create more tolerant societies elsewhere. In 1663, a full charter was given to Rhode Island and Providence Plantation. The charter guaranteed religious freedom for all persons. In no small measure, Anne Hutchinson helped chart the American course toward liberty.