U. S. v Korematsu (Japanese-American Exclusion Case)

United States v Korematsu (The Japanese-American Exclusion Case)

In the 2018 case of Trump v Hawaii, the Supreme Court upheld the Trump Administration’s policy of banning most residents of seven countries from entering the US. The Court upheld the ban on a 5 to 4 vote, rejecting arguments that the ban was “anti-Muslim.” Curiously, Chief Justice John Roberts in his opinion for the Court, chose to say something about a case decided in the middle of World War II, Korematsu v. United States. The Chief Justice wrote, “Korematsu was gravely wrong the day it was decided, has been overruled in the court of history, and—to be clear—has no place in law under the Constitution.”

It seemed to be the one thing all nine of the justices could agree on. Korematsu was a terrible decision. So how did it happen?

Fred Korematsu’s father emigrated from Japan in 1904. He settled in San Francisco in 1905, the same year delegates met there to form the Asiatic Exclusion League. The press regularly warned about the growing “yellow peril.” Fred’s mother immigrated to the United States from Japan nine years later.

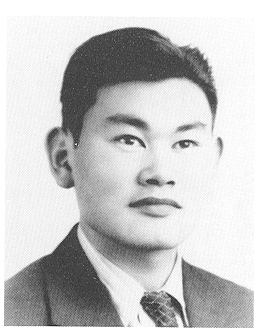

Fred was the third son, born in 1919. Fred was not his given name. An elementary school teacher found his real name to be unpronounceable and asked him one day, “How would you like to be called ‘Fred’?”

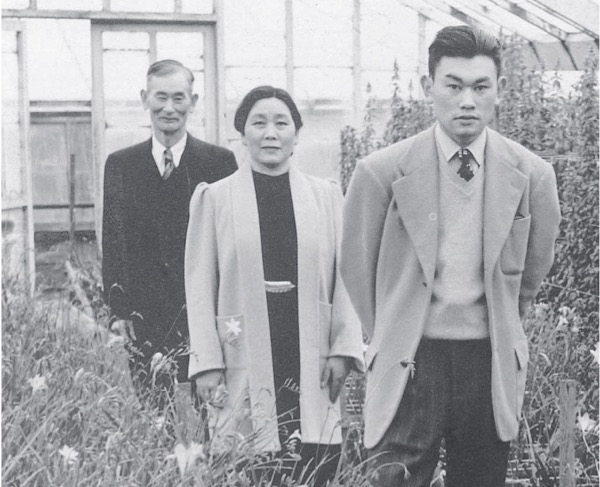

Fred’s family ran a flower nursery in East Oakland. They regularly attended samurai movies at the Buddhist temple, but the family converted to Christianity. Fred attended church every Sunday and became a member of a Boy Scout troop. Almost all of Fred’s friends were white; few Japanese-Americans lived close by.

Korematsu with his parents in their family nursery in East Oakland, California

Fred was not the favored son. He helped at the nursery, but never liked the work. He got into more mischief than his brothers. Fred was shy and reserved, but he loved to dance to Big Band music. He liked competitive sports and participated on his high school tennis and swim teams.

Fred said, “in high school, I felt equal.” In public, he felt different. He had to go to Chinatown because none of the barbers near his home would cut his hair. Some restaurants would refuse to serve him.

Despite the discrimination, Fred was patriotic. In 1940, when Congress instituted its first peacetime draft, Fred registered on the first day. He was classified 4-F because of a gastric ulcer. He tried to volunteer for navy radio work, but wasn’t accepted. He got a job in a shipyard and was about to be promoted to foreman when we was expelled from the union because of his race. The same thing happened at his next job, at the Golden Gate Iron Works.

On the morning of December 7, 1941, Fred Korematsu was on a hillside in a car with his girlfriend listening to music on the car radio. The music was interrupted with a bulletin announcing the bombing of Pearl Harbor. Fred said he thought it “was a dream.” “It burned me up that this happened,” he said. He told his Italian-American girlfriend, “I better get back home.”

Within hours of the bombing, President Roosevelt declared all Japanese immigrants over the age of fourteen to be “enemy aliens” . . . . Continued