Source:

The Life of Luther Written by Himself

Collected and arranged by M. Michelet

Translated by William Hazlitt

(London, 1904)

pp. 75-78

Introduction

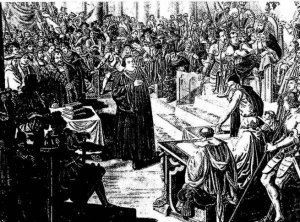

Meantime, the emperor had summoned Luther to appear at Worms*, before the imperial diet; and the two parties were now about to meet face to face.

* The emperor's mandate was in the following terms:—"Honourable, dear, and devoted Luther.—Ourself and the states of the holy Roman empire, assembled at Worms, having resolved to demand an explanation from you on the subject of your doctrines and your books, we forward you a safe-conduct, to ensure your personal immunity from danger. We would have you immediately set forth on your journey hither, so that within twenty days of the receipt of our mandate, you may appear before us and the states. You have neither violence nor snares to fear. Relying upon our imperial word, we expect your obedience to our earnest wishes.".—Luther's Werkr, ix. 10b.

Even in the diet at Worms, there were partisans of Luther. In one of the sittings, somebody openly produced a paper, setting forth that four hundred nobles had sworn to defend him, and after reading it, cried out,"Buntschuh! Buntschuh!"1 —the rallying word of the insurgent peasantry. The Catholics, indeed, were not altogether sure of the emperor. During the diet, Hutten writes: "Caesar has, they say, made up his mind to side with the pope." In the town itself, among the populace, the Lutherans were numerous. Hermann Busch writes to Hutten, that a priest, coming cut of the imperial palace with two Spanish soldiers, attempted, at the very gates of the palace, to take away eighty-four copies of the Captivity of Babylon, that a man was selling, but was soon compelled by the indignant people to take refuge in the interior of the palace. At the same time, to induce Hutten at once to take up arms, he describes to him the Spaniards insolently parading about the streets of Worms on their mules, and making the people give way before them.

"The audacity of the Romanists," he writes to Hutten, "grows greater and greater; for, as they say, you bark, but don't bite."

Another man of letters, Helius Eobanus Hessus, also urged Hutten to take up arms for Luther. "Franz Von Sickengen will be there to back us, and you two together, I predict, will be the thunder and lightning that shall crush the monster of Rome."

The hostile biographer of Luther, Cochlaeus, relates in a satirical manner, the reformer's progress to the diet:—"A chariot was prepared for him in the form of a closed litter. Around him were many learned personages; the provost Jonas, Doctor Schurf, the theologian Amsdorff, &c. Wherever he passed, there was a great concourse of people. In the taverns was good cheer, joyous libations, and even music. Luther himself, to draw all eyes upon him, played the harp like another Orpheus—a shaved and capuchined Orpheus.

Although the safe-conduct of the emperor prohibited him from preaching on his route, he yet preached at Erfurt on Easter Sunday, and had his sermon printed." This portrait of Luther by no means accords with the one given of him by a friendly contemporary, Mosellanus, some time before the diet:—

"Martin is of the middle height; cares and studies have made him so thin, that one may count all the bones in his body; yet he is in all the force and verdure of his age. His voice is clear and piercing. Powerful in his doctrine, wonderful for his knowledge of the Scriptures, every one of the verses of which, almost, he could recite one after another, he learned the Greek and Hebrew for the purpose of comparing and weighing the translations of the Word. He is never at a loss, and has at his disposition a world of thought! and words. In his conversation he is agreeable and easy, and there is nothing hard or austere in his air. He even permits himself to enjoy the pleasures of life. In society he is gay, jocund, and unembarrassed; and preserves a perfect serenity of countenance, despite the atrocious menaces of his adversaries. It is difficult to believe that this man could undertake such great things without Divine protection. The only reproach that almost everybody joins in making against him, is, that he is too caustic in his replies— hesitating at no bitterness of expression when he is angry."

....We are indebted to Luther himself for a fine narrative of what took place at the diet—a narrative in all essential points conformable with that which has been given of it by his enemies:—

pp. 79-85

"The herald summoned me on the Tuesday in Holy Week, and brought me safe-conducts from the emperor, and from several princes. On the very next day, Wednesday, these safe conducts were, in effect, violated at Worms, where they condemned and burned my writings. Intelligence of this reached me when I was at Worms. The condemnation, in fact, was already published in every town, so that the herald himself asked me whether I still intended to repair to Worms.

"Though, in truth, I was physically fearful and trembling, I replied to him—' I will repair thither, though 1 should find there as many devils as there are tiles on the house tops.' When I arrived at Oppenheim, near Worms, Master Bucer came to see me, and tried to dissuade me from entering the city. He told me that Glapion, the emperor's confessor had been to him, and had entreated him to warn me not to go to Worms; for that if I did, I should be burned. I should do well, he added, to stop in the neighbourhood, at Franz Von Sickengen's, who would be very glad to entertain me.

"The wretches did this for the purpose of preventing me from making my appearance within the time prescribed; they knew that if I delayed only three more days, my safe-conduct would have been no longer available, and then they would have shut the gates in my face, and, without hearing what I had to say, have arbitrarily condemned me. I went on, then, in the purity of my heart, and on coming within sight of the city, at once sent forward word to Spalatin that I had arrived, and desired to know where I was to lodge. All were astonished at hearing of my near approach; for it had been generally imagined that, a victim to the trick sought to be practised on me, my terrors would have kept me away.

Two nobles, the seigneur Von Hirschfeldt and John Schott, came to me by order of the elector, and took me to the house in which they were staying. No prince came at the time to see me, but several counts and other nobles did, who gazed at me fixedly. These were they who had presented to his majesty the four hundred articles against ecclesiastical abuses, praying that they might be reformed, and intimating that they would take the remedy into their own hands if need were. They had all been freed by my gospel!"

"The pope had written to the emperor desiring him not to observe the safe-conduct. The bishops urged his majesty to comply with the pope's request, but the prince and the states would not listen to it; for such conduct would have excited a great disturbance. All this brought me still more prominently into general notice, and my enemies might well have been more afraid of me than I was of them. The landgrave of Hesse, still a young man at that time, desired to have a conference with me, came to my lodgings, and after a long interview said, on going away : 'Dear doctor, if you be in the right, as I think you are, God will aid you.'

"On my arrival, I had written to Glapion, the emperor's confessor, entreating him to come and see me at his first leisure; but he refused, saying it would be useless for him to do so.

"I was then cited, and appeared before the whole council of the imperial diet in the town hall, where the emperor, the electors, and the princes, were assembled. Dr. Eck, official of the archbishop of Treves, opened the business by saying to me, first in Latin, and then in German:

"'Martin Luther, his sacred and invincible majesty, with the advice of the states of the empire, has summoned you hither, that you may reply to the two questions I am now about to put to you: do you acknowledge yourself the author of the writings published in your name, and which are here before me, and will you consent to retract certain of the doctrines which are therein inculcated ?'

I think the books are mine,' replied I. But immediately, Dr. Jerome Scburff added: 'Let the titles of the works be read.' When they had read the titles, I said: Yes, the books are mine.'

"Then he asked me: ' "Will you retract the doctrines therein?'

I replied: 'Gracious emperor,—as to the question whether I will retract the opinions I have given forth, a question of faith in which are directly interested my own eternal salvation, and the free enunciation of the Divine Word—that word which knows no master either on earth or in heaven, and which we are all bound to adore, be we as great as we may—it would be rash and dangerous for me to reply to such a question, until I had meditated thereupon in silence and retreat, least I incur the anger of our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ, who has said, He who shall deny me before men, I will deny him before my Father which is in heaven. I therefore entreat your sacred majesty to grant me the time necessary to enable me to reply with full knowledge of the point at issue, and without fear of blaspheming the word of God, or endangering the salvation of my own soul.' They gave me till the next day at the same hour.

"The following morning I was sent for by the bishops and others who were directed to confer with me, and endeavour to induce me to retract. I said to them: 'The Word of God is not my word : I therefore cannot abandon it. But in all things short of that, I am ready to be docile and obedient.' The margrave Joachim then interposed, and said : 'Sir doctor, as I understand it, your desire is to listen to counsel and to instruction on all points that do not trench upon the Word?' 'Yes,' I replied, 'that is my desire.'

"Then they told me that I ought to place myself entirely in the hands of his majesty, but I said, I could not consent to this. They asked me, whether they were not themselves Christians, and entitled to have a voice in deciding the questions between us, as well as I? Whereunto I answered, 'That I was ready to accept their opinions in all points which did not offend against the Word, but that from the Word I would not depart,' repeating, that as it was not my own I could not abandon it. They insisted that I ought to rely upon them, and have full confidence that they would decide rightly. 'I am not,' rejoined I, ' by any means disposed to place my trust in men who have already condemned me without a hearing, although under safe-conduct. But to show you my zeal and sincerity, I tell you what I will do; act with me as you please; I consent to renounce my safeconduct, and to place it unreservedly in your hands.' At this my lord Frederic de Feilitsch observed, 'Truly this is saying quite enough, or indeed, too much.'

"By and by they said: 'Will you, at all events, abandon some of the articles ?' I replied: ' In the name of God I will not defend for a moment any articles that are opposed to the Scripture.' Hereupon two bishops slipped out, and went and told the emperor I was retracting. At this a message came to me, asking whether I really consented to place myself in the hands of the emperor and of the diet? I answered: that I had consented to nothing of the sort, and should never consent to it. So I went on, resisting, alone, the attempts of them all, for Dr. Schurff and my other friends had become angry with me for my obstinacy, as they called it. Some of my disputants said to me, that if I would come over to them, they would in return, give up to me and abandon the articles which had been condemned at the council of Constance. To all which I simply replied: ' Here is my body, here my life: do with them as you will.'

"Then Cochlaeus came up to me, and said: 'Martin, if thou wilt renounce the safe-conduct, I will dispute with thee.' I, in my simplicity and good faith, would have consented to this, but Dr. Jerome Schurff replied, with an ironical laugh: ' Ay, truly, that were a good idea—that were a fair bargain, i'faith; you must needs think the doctor a fool.' So I refused to give up the safe-conduct. Several worthy friends of mine, who were present, had already, at the bare mention of the proposition, advanced towards me, as if to protect me, exclaiming to Cochlaeus; ' What, you would carry him off a prisoner, then! That shall not be.'

"Meantime, there came a doctor of the retinue of the margrave of Baden, who essayed to move me by fine flourishes: I ought, he said, to do a very great deal, to grant a very great deal, for the love of charity, that peace and union might continue, and no tumult arise. All, he urged, were called upon to obey his imperial majesty, as being the supreme authority; we ought all to avoid creating unseemly disturbances, and therefore, he concluded, I ought to retract. 'I will,' replied I, 'with all my heart, in the name of charity, do all things, and obey in all things, which are not opposed to the faith and honour of Christ.'

"Then the chancellor of Treves said to me: 'Martin, thou art disobedient to his imperial majesty; wherefore depart hence, under the safe-conduct which has been given thee.' I answered: 'It has been as it pleased the Lord it should be. And you,' I added, 'do all of you, on your part, consider well the position in which you are.' And so I departed, in singleness of heart, without remarking or comprehending their machinations.

"Soon afterwards they put in force their cruel edict—that ban, which gave all ill men an opportunity of taking vengeance with impunity on their personal enemies, under the pretext of their being Lutheran heretics; and yet, in the end, the tyrants found themselves under the necessity of recalling what they had done.

" And this is what happened to me at Worms, where I had no other aid than the Holy Spirit."

pp. 85-95

We find other curious details in a more extended narrative of the conference at Worms—written immediately afterwards, by Luther himself, in all probability, though he speaks in the third person:

"The day after, at four in the afternoon, the imperial chamberlain, and the herald who had accompanied him from Wittemberg, came to him at his inn, The Court of Germany, and conducted him to the town hall, along bye-ways, in order to avoid the crowds which had assembled in the leading streets. Notwithstanding this precaution, there were numbers collected at the gates of the town hall, and who essayed to enter with him, but the guards kept them back. Many persons had got upon the roofs of houses to see Dr. Martin. As he proceeded tip the kail, several noblemen successively addressed to him words of encouragement. ' Be bold,' said they, 'and fear not those who can kill the body, but are powerless against the soul.' Monk,' said the famous captain George Freundesberg, putting his hand cheeringly on Martin's shoulder, 'take heed what thou doest; thou art adventuring on a more perilous path than any of us have ever trod. But if thou art in the right, God will not abandon thee.' Duke John of Weimar had previously supplied the doctor with the money for his journey.

"Luther made his answers in Latin and German.

"The official opened the proceedings: ' Martin Luther, yesterday you acknowledged the books published in your name. Do you retract those books, or not ? This is the question we before addressed to you, and which you declined answering, under the pretext that it was a question of faith we were putting, and that you had need of time for reflection ere you replied, though a theologian like you must know very well that a Christian should always be ready to answer any questions touching his faith. Explain yourself now. Will you defend all your writings, or disavow some of them?'

" 'Most serene emperor,' replied Martin, 'illustrious princes, most clement lords, I am again before you, appearing at the hour appointed, and supplicating you to listen to me with benevolence and equity. If in my statement' or my replies, I should omit to give you the titles of honour due to you, if I offend against the etiquette of courts, you will, I trust, pardon me, for I have never been accustomed to palaces; I am nothing but a poor monk, the inmate of a humble cell, who have, I assure you, never preached aught, never written aught, but in singleness of heart, and for the glory of my God, and the honour of the Gospel.

"'Most serene emperor, and princes of the empire: to the two questions put to me yesterday, whether I acknowledged as mine the books published in my name, and whether I persevered in defending them, I answer now, as before, and as I will answer to the hour of my death—Yes, the books which have been published by me, or which have been published in my name, are mine; I acknowledge them, I avow them, and will always avow them, so long as they remain the same as I sent them forth, undistorted by malice, knavery, or mistaken prudence. I acknowledge, further, that whatever I have written, was first matured in my mind by earnest thought and meditation.

"'Before replying to the second question, I entreat your majesty and the states of the empire to consider that my writings do not all treat of the same matter. Some of them are preceptive, destined for the edification of the faithful, for the advancement of piety, for the amelioration of manners; yet the bull, while admitting the innocence and advantage of such treatises, condemns these equally with the rest. If I were to disavow them, what practically should I be doing? Proscribing a mode of instruction which every Christian sanctions, and thus putting myself in opposition to the universal voice of the faithful.

"'There is another class of writings in which I attack the papacy and the belief of the papists, as monstrosities, involving the ruin of sound doctrine and of men's souls. None can deny, who will listen to the cries and the evidences of the conscience within, that the pope's decretals have thrown utter disorder into Christianity, have surprised, imprisoned, tortured the faith of the faithful, have devoured as a prey this noble Germany, for that she has protested alond against lying tales, contrary to the gospel and to the opinions of the Hither. If I were to retract these writings, I should lend additional strength and audacity to the Roman tyranny, I should open the floodgates to the torrent of impiety, making for it a breach by which it would rush in and overwhelm the Christian world. My recantation would only serve to extend and strengthen the reign of iniquity; more especially when it should be known that it was solely by order of your majesty, and your serene highnesses, that I had made such retraction.

"'Finally, there is another class of works, which have been published under my name; I speak of those books of polemics, which I have written against some of my adversaries, advocates of the Roman tyranny. I have no hesitation in admitting that in these I have shown greater violence than befitted a man of my calling; I do not set up for a saint, I do not say that my conduct has been above reproach; my dispute is not about that conduct, but about the doctrine of Christ. But though I have been violent overmuch at times, I cannot consent to disavow these writings, because Rome would make use of the disavowal, to extend her kingdom and oppress men's souls.

"'A man, and not God, I would not seek to shield my books under any other patronage than that with which Christ covered his doctrine. When interrogated before the high-priest, as to what he taught, and his cheek buffeted by a varlet: "If I have spoken evil," he said, " bear witness of the evil." If the Lord Jesus, who knew himself incapable of sin, did not reject the testimony which the vilest mouths might give respecting his Divine Word, ought not I, scum of the earth that I am, and capable only of sin, to solicit the examination of my doctrines ?

"'I therefore, in the name of the living God, entreat your sacred majesty, your illustrious highnesses, every human creature, to come and depose what they can against me, and, with the Prophets and the Gospel in their hands, to convict me, if they can, of error. I stand here, ready, if any one can prove me to have written falsely, to retract my errors, and to throw my books into the fire with my own hand.

"' Be assured I have well weighed the dangers, the pains, the strife, and hatred that my doctrine will bring into the world; and I rejoice to see the word of God producing, as its first fruits, discord and dissension, for such is the lot and destiny of the Divine Word, as our Lord has set forth: I came not to send peace, but a sword, to set the son against his father.

"'Forget not that God is admirable and terrible in all his counsels ; and beware, least, if you condemn the Divine Word, that Word send forth upon you a deluge of ills, and the reign of our noble young emperor, upon whom, next to God, repose all our hopes, be speedily and sorely troubled.

"'I might here, in examples drawn from Holy Writ, exhibit to you Pharaoh, king of Egypt, and the kings of Israel, ruined from seeking to reign at first by peace, and by what they termed wisdom. For God confounds the hypocrite in his hypocrisy, and overturns mountains ere they know of their fall: fear is the work of God.

"'I seek not herein to offer advice to your high and mighty understandings ; but I owed this testimony of a loving heart to my native Germany. I conclude with recommending myself to your sacred majesty and your highnesses, humbly entreating you not to suffer my enemies to indulge their hatred against me under your sanction. I have said what I had to say.'

"Then the emperor's orator hastily rose, and exclaimed that Luther had not directed himself to the question; that what the assembly had to do was not to listen to a discussion whether councils had decided right or wrong, but to ascertain from Luther whether he would retract; this was the question to which he had to reply: yay or no.

"Thereupon Luther resumed in these words:

"'Since then your imperial majesty and your highnesses demand a simple answer, I will give you one; brief and simple, but deprived of neither its teeth nor its horns. Unless I am convicted of error by the testimony of Scripture, or by manifest evidence (for I put no faith in the mere authority of the pope, or of councils, which have often been mistaken, and which have often contradicted one another, recognising, as I do, no other guide than the Bible, the Word of God), I cannot and will not retract, for we must never act contrary to our conscience.

"'Such is my profession of faith, and expect none other from me. I have done: God help me! Amen !'

"The states retired to deliberate; on their return, the official thus addressed Luther:

"'Martin, you have assumed a tone which becomes not a man of your condition; and you have not answered the questions put to you. Doubtless you have written some pieces which are in no way liable to censure ; and had you retracted those works of yours, in which you inculcate your mischievous errors, his majesty, in his infinite goodness, would not have permitted any proceedings to be taken against those which contain only right doctrine. You have resuscitated dogmas which have been distinctly condemned by the council of Constance, and you demand to be convicted thereupon out of the Scriptures. But if every one were at liberty to bring back into discussion points which for ages have been settled by the church and by councils, nothing would be certain and fixed, doctrine or dogma, and there would be no belief which men must adhere to under pain of eternal damnation. You, for instance, who today reject the authority of the council of Constance, tomorrow may, in like manner, proscribe all councils together, and next the fathers, and the doctors; and there would remain no authority whatever, but that individual word which you call to witness, and which we also invoke. His majesty, therefore, once more demands a simple and precise answer, affirmative or negative; will you defend all your principles, as catholic principles, or are there any of them which you are prepared to retract?'

"Then Luther besought the emperor not to permit him to he thus called upon to belie his conscience, which was bound up with the sacred writings. They had required of him a categorical answer, and he had given one. He could only repeat what he had already declared : that unless they proved to him by irresistible arguments that he was in the wrong, he would not go back a single inch; that what the councils h id laid down, was no article of faith ; that councils had oft an erred, had often contradicted each other, and that their testimony, consequently, was not convincing ; and that lie could not disavow what was written in the inspired books.

"The official sharply observed, that Luther could not show the councils to have erred.

"Martin said he would undertake to do so at any time that might be assigned him.

"By this time, the evening drawing in, it grew dark, and the diet arose. When the man of God left the town hall to return to his lodging, he was followed and insulted by some Spaniards.**

"Next day, the emperor*** sent for the electors and states to discuss with them the form of the imperial ban against Luther and his adherents. The safe-conduct, however, was retained in it.****

"Meantime, Luther was visited by a great number of princes, counts, barons, prelates, and other persons of distinction, lay and ecclesiastical. ['The doctor's little room,' writes Spalatin, 'could not contain all the visitors who presented themselves. I saw among them duke William of Brunswick, the landgrave, Philip of Hesse, count Wilhebn of Henneburg, the elector Frederick, and many others.']

"On the Wednesday following, (eight days after his first appearance before the diet,) he was requested by the archbishop of Treves to wait upon him. Luther accordingly presented himself before that prelate, attended by the imperial herald, and accompanied by the friends who had followed him from Saxony and Thuringia. In the apartment of the archbishop they found assembled Joachim of Brandenburg, the elector George, the bishops of Augsburg and Brandenburg, count George, grand-master of the Teutonic order; John Boeck of Strasburg, and Dr. Peutinger. Veh, (Vehus,) chancellor of Baden, opened the proceedings, in the name of those present, by declaring that they had not invited Luther there with any view to polemical discussion, but out of a pure feeling of charity and kindness towards him.

"Then Veh commenced a long harangue on the obedience due to the church and its decisions, to the councils and their decrees. He maintained that the church, like any other power, had its constitutions which might be modified according to the requirements of the particular nations to which they were applied, the diversity of manners, of climate, of epochs; and that herein lay the apparent contradictions which Luther had denounced as existing in the internal system of the church. These contradictions, in fact, only proved more emphatically the religious care with which the church regulated its spiritual administration, and in no degree affected the integrity of the catholic dogma. That dogma was yesterday what it is to-day, and what it will continue to be till the end of time. He called Luther's attention to the disturbances to which his innovations were everywhere giving rise. 'See,' said he, your book, De Libertate Christiana: what does that teach men? To throw off every species of subjection— to erect disobedience into a maxim. We no longer live at a time when every child of the Christian family had but one heart and one soul; when the precept was one, like the society; when the rule was one, like the precept. It became necessary to modify all this, when time itself had modified society; but without the catholic dogma ever receiving the slightest prejudice. I am quite aware, Martin,' he added, 'that many of your writings breathe a sweet odour of piety; but we have judged the general spirit of your works, as we judge a tree, not by its flowers, but by its fruits. The advice given you by the states of the empire is given in a desire of peace, with all good feeling towards yourself. Those states were established by God to watch over the security of a people whose tranquillity your doctrines are calculated to disturb. To resist them is to resist God. Doubtless, it is better to obey God than to obey man; but do you think that we, any more than yourself, are deaf to his word, or have not meditated thereupon?'

"Luther, after having expressed his thanks for the peaceful and charitable expressions made use of towards him, proceeded to answer what Veh had said respecting the authority of councils. He maintained that the council of Constance had erred in condemning this proposition of John Huss: 'Tantum una est sancta, universalis ecclesia qua est numerus prmdestinalorum.' ' No retractation!' he said, in conclusion, with an animated and firm voice: "you shall have my blood, my life, rather than a single word of retractation; for it is better to obey God than to obey man. It is no fault of mine that this matter creates confusion among you. I cannot prevent the word of Christ becoming a stumbling block to men. If the sheep of the good Shepherd were fed upon evangelical marrow, faith would live, and our spiritual masters would be honest and trustworthy. I know well that we must pay obedience to the civil magistrate, even though he be not a man after God's own heart; and I am quite ready to pay that obedience in all things that does not shut out the Word of God." Luther was then about to take his leave, but he was told to remain, and Veh pressingly urged upon him his previous arguments, and conjured him to submit his writings to the decision of the princes and states of the empire.

"Luther gently replied: ' I would fain have it understood, that I do not decline the judgment of the emperor and of the states; but the word of God, on which I rely, is to my eyes so clear, that I cannot retract what I have said, until a still more luminous authority is opposed to that Word. St. Paul has said—If an angel from heaven preach any other gospel to you let him be accursed; and I say to you, do not oner violence to my conscience, which is chained up with the Scripture.'

"The meeting then broke up; but the archbishop of Treves retained Luther, and went with him into another apartment. Jerome Schurff and Nicholas followed. John Eck, and Cochlaeus, dean of the church of the Holy Virgin at Francfort, were already in the room. Eck addressed Luther:—

" ' Martin,' said he, ' there is no one of the heresies which have torn the bosom of the church, which has not derived its origin from the various interpretation of the Scripture. The Bible itself is the arsenal whence each innovator has drawn his deceptive arguments. It was with biblical texts that Pelagius and Arius maintained their doctrines Arius, for instance, found the negation of the eternity of the Word—an eternity which you admit, in this verse of the New Testamcn—Joseph knew not his wife till she had brought forth her first-born son; and he said, in the same way that you say, that this passage enchained him. When the fathers of the council of Constance condemned this proposition of John Huss— The church of Jesus Christ is only the community of the elect, they condemned an error; for the church, like a good mother, embraces within her arms all who bear the name of Christian, all who are called to enjoy the celestial beatitude.' Luther replied, reproducing all the arguments he had before made use of. Cochkeus took him by both hand;-, and conjured him to restore peace to the church. Luther was inflexible, and so they separated.

"In the evening, the archbishop of Treves sent word to Luther that, by order of the emperor, his safe-conduct had been extended two days, and requested him to wait upon him the next day, to have another conference.

"Peutinger and the chancellor of Baden came to see Luther next morning, and renewed the conversation of the preceding evening, using every argument they could devise to induce him to submit his writings to the judgment of the emperor.

"'Yes,' said Luther, ' I am ready to do so, if you will come and controvert me, Bible in hand; otherwise, not. God has said by the mouth of the prophet-king: Put not your trust in princes, for in them there is no salvation; and, by the mouth of Jeremiah, Cursed be he who putteth his trust in man.' They urged him still more pressingly: «I will submit everything to the judgment of man,' said he, ' except the Word of God.' They then left him, saying they would return in the evening, when they hoped to find him in a better frame of mind. They came; but it was all in vain.

"There was another interview with the archbishop. In this last conference, the prelate said: 'But, dear doctor, if you will not submit this matter to the diet, or to a council, by what means shall we avert the troubles which menace the church? What remedies can we apply?'

"Luther replied: 'Nothing better can be said in this case than was said, according to St. Paul, by Gamaliel: If this work be of men, it will come to nought. The emperor and the states may write to the pope thus: if the work of Luther is not an inspiration from on high, in three years it will be no more spoken of.'

"The archbishop persisted: 'Suppose,' said he, 'that we made from your books faithful extracts of articles we object to. Would you submit them to a council?'

"'Provided they were none of those,' returned Luther, 'which the council of Constance has already condemned.'

"'But if they were?'

"Then,' said Luther, 'I would not consent to submit them to a council, for I am certain that the decrees of that council condemned the truth : I would rather lose my head than abandon the divine word. In what concerns the word of God and the faith, every Christian is as good a judge for himself as the pope can be for him; for each man must live and die according to that faith. The word of God is the common heritage of the whole Christian world, each member of which is competent to explain it. The passage of St. Paul (1 Corinthians, xiv.): If anything be revealed to another that sitteth by, let the first hold his peace, proves clearly that the master must follow the disciple, if the latter understand the .word of God better than he himself does."

"And thus ended the conference.

"Soon after this, the official sent for Luther, and in the presence of the arch-chancellor, read to him the imperial sentence.

"'Luther,' he added, 'since you have not chosen to listen to the counsels of his majesty and of the states of the empire, and to confess your errors, it is now for the emperor to act. By his order, I give you twenty days, wherein to return to Wittemberg, secure under the imperial safe-conduct, provided that on your way you excite no disorders by preaching or otherwise.'

"As the official concluded, Sturm, the herald, inclined his staff, in token of respect.

"Luther bowed, and said: 'Be it as the Lord pleases; blessed be the name of the Lord.' He added the expression of his warm gratitude towards the emperor personally, and towards his ministers, and the states of the empire, for whom, he affirmed, with his hand on his heart, he was ready to sacrifice life, honour, reputation— all, except the word of God.

"Next day, 26th April, after a collation given him by his friends, the doctor resumed the route to Wittenberg."

-------------

Notes:

**" Martin had spoken more than two hours, repeating in Latin what he first said in German. The perspiration rolled down his face, his face was haggard, and he needed rest. On his return to his lodgings, he found on the table a small can of Eimbeck beer, that had been sent him. He emptied it at one draught. On putting down the can, he asked: ' Who made me this present?' ' Duke Eric of Brunswick,' replied Amsdorf. ' Ah,' said Luther, as duke Eric has this day thought of me, so may God one day think of him.'"—Audin.

*** Spalatin relates in his Annals (50), that after Luther's second appearance, the elector of Saxony, on his return from the town hall, sent for him and said: " Doctor Martin has spoken well before the diet, but somewhat too boldly."

**** "The imperial rescript was in the following terms: 'Our ancestors, kings of Spain, archdukes of Austria, and dukes of Burgundy, protectors a:ii defenders of the catholic faith, have preserved its inviolability with their swords and with their blood, and have ever taken care that the decrees of the church should meet with that obedience which they are entitled to. We shall not lose sight of these examples, we shall walk in the footsteps of our ancestors, and defend, with all our might, that faith which we have received as a heritage. And, therefore, a monk having dared to come forward and assail at once the dogmas of the church and the head of the Catholic communion, persisting obstinately in the errors into which he has fallen, and refusing to retract, we have deemed it essential to oppose ourselves to the further progress of these disorders, even though at the peril of our life, of our dignities, of the fortune of the empire, in order that Germany may not gully herself with the crime of perjury. We will not again hear Martin Luther, who has given ourself and the diet such manifest proofs of his inflexible obstinacy; and we order him to depart hence under the faith of tbe imperial safeguard we have given him, prohibiting him at the same time from preaching or exciting any commotion on his way."—AUDIN