by Douglas O. Linder (2019)

The German submarine maneuvered along the Long Island shoreline. Shortly after midnight, on June 13, 1942, six men got into a rubber boat. Two crew members began paddling toward the beach, their task made more difficult by the four boxes of explosives and other equipment carried along with them. Waves nearly capsized the boat, but they made their landing. While two men used an attached rope to guide the rubber boat back toward the sub, the four members of the sabotage team changed from their military uniforms into civilian garb.

Ponte Vedre Beach

Four days later, a similar scene unfolded at Ponte Vedra, near Jacksonville, Florida. A second four-member German sabotage team made a beach landing, changed into civilian clothes, and buried boxes of explosives. This team walked along the beach for hours before catching a bus that took them into Jacksonville.

Sabotage School

The eight Germans who landed on beaches were all graduates of a training school for saboteurs. The idea for a sabotage effort in America developed in late 1941, soon after a German spy network in the United States imploded when one of the spies turned out to be a double agent. The double agent identified dozens of Nazi spies working in the U.S. Thirty-three spies were rounded up and convicted in September, 1941.

The collapse of the spy ring infuriated Hitler, who demanded that Nazi intelligence officers immediately initiate a sabotage plan against America. One of the intelligence officers confronted by Hitler, Admiral Wilhelm Canaris, knew that any such sabotage program faced long odds. He said, that in any program involving more than a small handful of men “someone always talks.” Nonetheless, he knew better than to cross the Fuehrer. So “Operation Pastorius” was born.

Walter Kappe

Walter Kappe was tapped to prepare candidates for the sabotage effort. Ten men were identified who spoke good English and had spent time in the United States, and eight of those made the cut to participate in the training. The eight men, aged 22 to 39, were George Dasch, Ernest Burger, Heinrich Heinck, Richard Quirin, Edward Kerling, Herbert Haupt, Hermann Neubauer, and Werner Thiel. The eight men, by the end of the training, were split into two teams of four, one headed by Dasch and the other by Kerling.

Kappe based his sabotage school at a farm near Brandenburg. The property included a main house, a greenhouse, a gymnasium, two shooting ranges, and a two-room garage. The garage space was divided between a classroom and a laboratory.

The training program lasted three weeks. The men began each morning with calisthenics, then attended three-hour sessions on the use of explosives and timing devices. In the afternoon, they worked on their English and sat through lectures on American sabotage targets, including railroads, dams, and industrial sites. They studied maps and practiced water landings. They chose false names for themselves and created false personal histories. All instruction had to be memorized. Whatever notes they took were destroyed.

In their free time, they played soccer, took trips to Berlin, and drank at local taverns. Hiking along local roads, the men would sometimes sing popular American songs; “Oh, Susanna!” was one of their favorites.

The eight saboteurs

By the end of the program, each team had been given a set of targets. The team led by Dasch was to dynamite aluminum plants in Alcoa, Tennessee, East St. Louis, and Massina, New York, as well as a cryolite plant in Philadelphia. They also were assigned the job of sabotaging locks along the Ohio River. Kerling’s team was to focus mainly on railroads, including a station in Newark and the Hell Gate Bridge in New York.

After being given ten days to say their good-byes to families, the men returned to the school to receive final instructions written in secret ink. The men then returned to Berlin for three days of tours of aluminum plants, railroad yards, and canal locks. Instructors provided practical tips, such as how to strike and disable high-tension poles carrying electricity to plants. After a final farewell banquet, the men were given American money and sent on their way. They traveled first to Paris, then to the French coast where they boarded the submarines.

Things Go Awry

Only moments after their arrival on Long Island’s Amagansett Beach, the four would-be saboteurs saw, through a thick fog, a man walking towards them. The man turned out to be a coast guardsman named John Cullen. If the Germans had followed instructions, they would have overpowered Cullen, but they didn’t. Instead, when asked who they were and what they were doing, they claimed to be lost fisherman. They said they planned to stay on the beach until morning and then they “will be alright.” A fishy story indeed.

Cullen told the men to follow him back to the Amagansett station, but they refused. Dasch claimed that they lacked fishing permits and wanted to avoid trouble. Then he tried a different approach. He told Cullen that he assumed he would like to see his parents again, adding “Well, I wouldn’t want to kill you.” Dasch told Cullen to forget what he’d seen and then offered a bundle of money, $260 when it was counted at the Coast Guard station. Dasch gave his name as “George John Davis” and told Cullen, strangely, he’d soon hear some news about him from Washington. Dasch asked Cullen if he would recognize him again. Cullen told him that he would not.

While this conversation was happening, another member of the team, Ernest Berger, was dragging a bag through the sand. Then he took out writings in German, a package of German cigarettes, and his cap with the insignia of the German Marine Infantry in various places around the beach.

Coast Guardsmen at Amagansett Station in 1942

Cullen headed back to the station, ready to report and begin an investigation. Dasch and his group buried the boxes of explosives and their German military uniforms, then headed toward the highway, eventually finding railroad tracks that they followed to the station at Amagansett. While buying tickets to head towards New York City, Dasch complained to the agent about the lousy fishing and said that they were headed home. By 9 am, the men reached Manhattan. They split into two pairs and checked into the Hotel Governor Clinton and the Hotel Martinique.

That evening, over dinner and at the hotel, Dasch and Burger began to share their strong hatred for the Nazi government and their plan to not carry through with their instructions to commit sabotage. They each had their reasons. Dasch had lived in the United States for seventeen years, from 1922 to 1939. He'd worked jobs as a fry cook, a waiter, and a salesman. He'd spent a year in Hawaii in the Aviation Corps. In a book he later wrote, Dasch said he thought of the United States as "my country" and "I was proud of it." Burger was a former Nazi. He had participated in the "Beer Hall Putsch" of 1923 and worked as a Storm Trooper. But he left Germany in 1927, worked as a tool maker in the Midwest, joined the Wisconsin National Guard, and became a U.S. citizen in 1933. He returned to Germany shortly after gaining U.S. citizenship, but found himself on the wrong side of an intra-party dispute between the SS and the Storm Troopers. He was charged with falsification of papers and spent 17 months in prison. He never forgave the Nazi party, blaming the pressure they placed on his wife for her miscarriage and her breakdown. Fellow sabotage school graduate Herbert Haupt said of Burger that he hated the Gestapo "more than anything on earth."

Five days later, Dasch boarded a train at Pennsylvania Station and headed to Washington D.C. He planned to tell the whole story personally to FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover. The next morning, Dasch called a number at the federal government to ask who should call to report espionage. The operator suggested he try to Adjutant General’s Office. Dasch called the office, talked to a secretary, and reported that he had landed with a group of Germans. Then he called the FBI and got hold of an agent. The agent said he would send over some people to escort him to the Justice Department where he could tell his story.

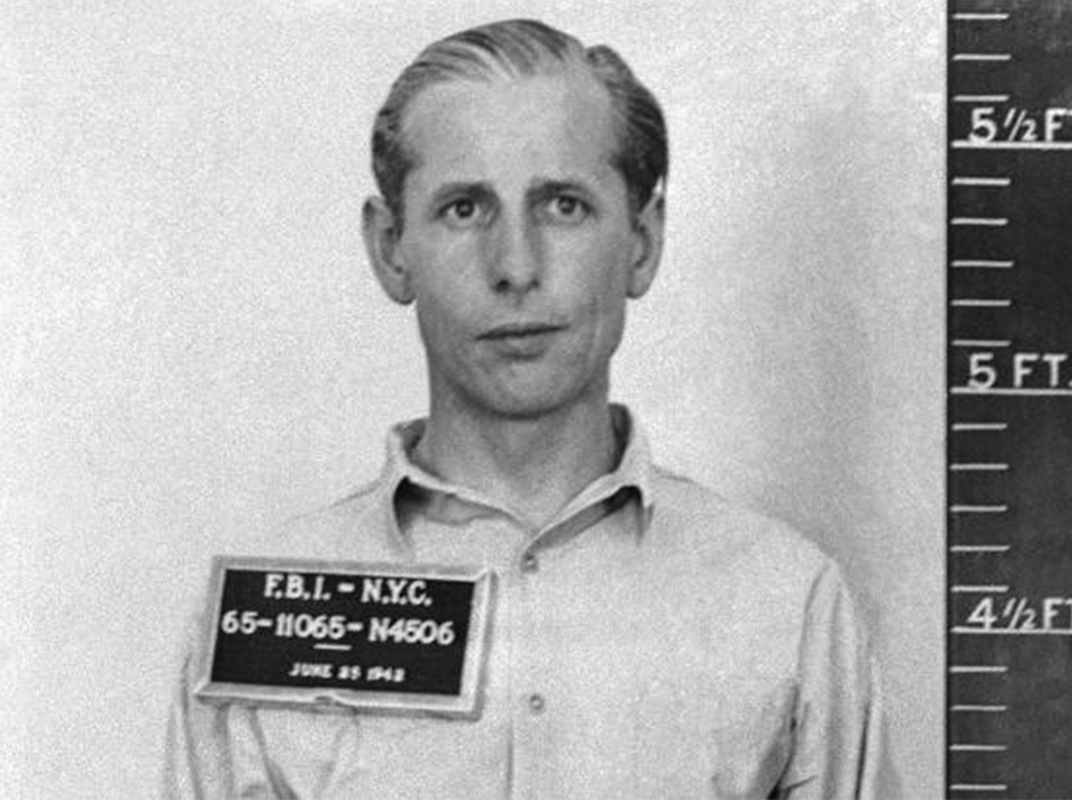

George Dasch

Agent Duane Traynor said he initially found Dasch’s story hard to believe. But he began to think differently when Dasch opened up his briefcase and displayed $82,550 in $50 bills.

In the days before Dasch’s journey to the capitol, the Coast Guard had made some interesting discoveries. They found Berger’s discarded cigarette package and uncovered the boxes buried in the sand. When they opened the boxes back at the station, they found detonators and time-bomb mechanisms, blasting caps, a cap with a swastika, uniforms, and other incriminating material.

Burger's cap, found at Amagansett Beach

Two days before Dasch met the FBI agents, the second sabotage team had made its landing in Florida. The four men arrived on Jacksonville Beach in their swimming suits, changed into civilian clothes, hopped a bus to Jacksonville, split into pairs, and checked into two hotels. Over the next two day they took two different trains to Cincinnati. From there, two men headed on to Chicago, while the other two took a train to New York City. On July 26, radio bulletins reported the news that German agents had landed by submarines on the East Coast.

FBI agents dig for evidence near Jacksonville, Florida

With Dasch providing all the answers he could give to the FBI, the round-up of the eight didn’t take long. Dasch gave the agents Burger’s room number at his New York hotel, and then Burger told agents where to find Quirin and Heinck. Kerling and Thiel were arrested outside of the Commodore Hotel in Cincinnati. Haupt and Neubauer were tracked down and arrested in Chicago.

The Trial

There would have to be a trial. But in what sort of court and where? The usual place for criminal trials, of course, is a civilian court—and, in the case of a violation of federal law, specifically a federal district court. But the Administration began thinking of another option—one that had last been used to try persons who conspired with John Wilkes Booth to assassinate President Lincoln.

A trial by a military commission would have several distinct advantages, as many in the Administration saw it. First, the proceeding could be kept largely secret. J. Edgar Hoover and the FBI had been basking in the public glory of the quick arrests of the saboteurs, and they preferred the public not to learn the real truth—that the quick arrests almost entirely was due to the information voluntarily provided by one of the saboteurs. In a civilian court, Dasch would almost certainly provide full details of his meetings with FBI agents and the helpful information he provided. Moreover, the Administration saw a benefit in the public not learning how easily two German submarines reached American beaches without being detected.

Second, a military commission would likely produce prompt convictions and severe sentences. Major General Myron Cramer, Judge Advocate General of the Army, worried that sabotage charges in a civilian court would not stick. None of the eight defendants had actually committed sabotage, and the planning and the landing on beaches might not be considered enough to constitute “an attempt” to commit sabotage. Yes, there entry into the United States almost certainly could be shown to violate immigration and custom laws, but those were at most two-year sentences. If the Administration wanted to inflict the ultimate penalty on most of the saboteurs, it would have to be done through a military tribunal, where the alleged crimes and process for trying them could be tailored as the government thought best.

President Roosevelt had told advisers that he considered the death penalty in this case “almost obligatory.” He compared the case to the hanging of British major John Andre, a spy who had assisted Benedict Arnold during the Revolutionary War. Any distinction between that case and this, Roosevelt said, “would be splitting hairs.”

There was, however, a potential problem with going the route of the military tribunal. The Supreme Court, in an 1866 case called Ex Parte Milligan, had reversed the conspiracy conviction of a pro-Confederate editor and agitator from Indiana named Lambdin Milligan. Milligan had been found guilty and was sentenced to be hanged by a military tribunal, but the Court held that Congress lacked the power to authorize the use of military commissions in places and at times when federal courts were open and operating.

But almost any case can be distinguished, and the Administration was reasonably confident they could distinguish this case from Ex Parte Milligan. The Administration could argue “the law of war” could be applied in a case like this where enemies have entered into U.S. territory during wartime with an intent to commit acts of sabotage.

On July 2, 1942, President Roosevelt issued a proclamation creating a military tribunal to try the saboteurs. The tribunal would consist of seven military officers. The commission would be empowered to make its own rules for the proceedings. The order stated that convictions could stand on a two-thirds vote and that no appeals could be made from the decisions of the commission. Final reviewing authority would vest only in the president himself. Attorney General Francis Biddle and Judge Advocate General Cramer were chosen to conduct the prosecution. Three military officers were appointed as defense counsel, one to represent George Dasch and the other two to represent the other seven defendants.

On July 7, the tribunal adopted a rule making the proceedings secret. A statement issued by the prosecution team explained, “We do not propose to tell to our enemies the answers to questions which are puzzling them.” Each day of the trial, the tribunal would provide a brief summary of what happened in the courtroom on the fifth floor of the Justice Department. Only on one day of the trial, and just for 15 minutes, were a group of reporters and photographers allowed to enter the room. They took notes, photographs of the eight rather ordinary-looking defendants, and examined some of the physical evidence assembled on a table.

Each of the eight defendants was charged with four crimes. Charge I accused the Germans of “secretly and covertly” entering the United States “in civilian dress, contrary to the law of war,” for “the purpose of committing acts of sabotage, espionage, and other hostile acts.” Charge II accused the defendants of knowingly “communicating with and giving intelligence to each other and enemies of the United States.” Charge III said the men “were found lurking or acting as spies” in civilian clothes “in or about the fortifications, posts, and encampments of armies of the United States and elsewhere.” Finally, Charge IV accused the defendants of plotting, planning, and conspiring “with each other and the German Reich” to commit each of the crimes specified in the first three charges.

The military tribunal in session on July 11, 1942

The trial had scarcely begun when defense lawyer Colonel Kenneth Royall argued that the presidential order establishing the military tribunal was “invalid and unconstitutional.” He contended that the federal district court in Washington was open and operating and that, under the precedent of Ex Parte Milligan, the trial had to be held there. Attorney General Biddle responded by expressing shock that a colonel in the army would challenge a proclamation signed by his commander-in-chief. Royall suggested that as military officers, members of the commission might find it “difficult or embarrassing” to “reach a judgment in favor of the defendants if the evidence should so indicate.”

Later, on the twelfth day of trial, Royall announced he would do what he first hinted he might do on July 8. He would go to federal court to challenge the validity of FDR’s order establishing a military tribunal. He did so only after being told by the president he was free to exercise his own judgment on the issue of having the proclamation tested. Roosevelt had been warned by Attorney General Biddle that denying authority to the defense to contest the tribunal “might tend to give the public the impression that the prisoners are not being given a fair trial.”

Royall prepared the paperwork for a petition for a writ of habeas corpus. It was the middle of the summer and the Supreme Court was not in session, so Royall decided to contact justices directly. After Justice Black told Royall he didn’t want to hear the case, he turned to Justice Owen Roberts. Roberts agreed that the matter “ought to be reviewed.” Justice Roberts told Royall that before the Supreme Court could hear the matter there needed to first be a ruling from the federal district court in Washington. On the evening of July 28, District Judge James Morris issued a brief ruling that petition of habeas corpus for Royall’s seven defendants was denied because the president’s order prevented any remedy for the defendants “in the courts of the United States.” The Supreme Court heard oral arguments in In Ex Parte Quirin over the course of the next two days. On July 31, the Court issued a short per curiam decision upholding the jurisdiction of the military tribunal to try the Germans. A full written decision would not be published for three months.

Biddle gives a document to a witness

The trial had both tedium and drama. Early in the trial, the defense attorney for George Dasch, Colonel Carl Ristine, insisted on reading into the record a 254-page single-spaced statement by his client. The boring and time-consuming (it took nearly two days to read) exercise so annoyed Biddle that refused to be in the courtroom for most of the reading.

More compelling was the personal testimony of each of the eight defendants. Dasch and Burger each testified that they never had any intention of committing sabotage. Rather, they said, they went through the sabotage school in the hope of getting out of Germany and finding refuse in the United States. Burger stated his desire succinctly. He wanted, he said, to “get out and get even.” Weighing against the testimony of Dasch and Burger, as well as the other defendants, was the fact that all had once lived in the United States, but then chosen to return to Germany, in some cases having to overcome great logistical difficulties to do so.

Various defendants testified that they attended sabotage school only to spare family and friends the reprisals by authorities that might have come had they refused to do so. Some defendants admitted that they had, while going through the sabotage training, intended to carry out their instructions in America, but changed their minds once they arrived in the United States. Two defendants, Kerling and Thiel, testified they had been subjected to slaps and hair-pulling by FBI agents during their interrogations. (FBI agents denied the charge, though they admitted to “rough” questioning of the two men.)

Five of the defendants during their trial

In his closing argument on July 31, Royall suggested that the tribunal give special consideration to two of his seven clients, Burger and Haupt. Both men, he argued, had made clear by their actions that they had no intention of committing sabotage and, on the contrary, entertained the hope of becoming loyal Americans, supportive of the war against Germany. Royall also reminded the tribunal that they had to find guilt beyond a reasonable doubt and that they should remember the precedent they established in this case might be used later by enemies against “our own boys” overseas. The evidence that any of the defendants actually committed the crimes laid out in the charges, Royall said, was pathetically thin. He told the commission that, even if they were to find his clients guilty, death would be an excessive punishment: “They did not hurt anybody. They did not blow up anything.”

Dasch’s defense attorney, Carl Ristine, told the commission that Dasch paid little attention to any of the instruction and sabotage school and could not have implemented any of the Reich’s plans even if he had wanted to. He ridiculed the prosecution’s argument that by failing to go to the FBI immediately after landing he deprived authorities of the opportunity to intercept the second submarine as it approached the Florida coast. How that information might have helped apprehend a submarine along a 700-mile-long coast, Ristine said, “I do not know.”

Closing for the prosecution, Myron Cramer said the commission needed to send a message to our enemies that they these attempts at sabotage would be dealt with harshly. He argued that the notion that a sophisticated German intelligence officer like George Kappe would send over “eight morons” who “had no intention with going through with this at all” was preposterous. He suggested that any change of heart they had about committing sabotage was due simply to their increased fear of getting caught after they arrived. Both Cramer and Biddle asked the commission to impose the death penalty for all eight defendants.

On August 3, after two days of deliberations, the tribunal announced its verdict. All eight men were found guilty and sentenced to death. President Roosevelt met with J. Edgar Hoover, Cramer, and others the next day to discuss, among other things, the manner of execution. Should they be shot, hanged, or electrocuted? Electrocuted, it turned out.

Roosevelt, Biddle, and Cramer also talked about whether two of the convicted men, Dasch and Burger, should have their sentences commuted. The decision was made to commute their sentences to life in prison because of “their assistance…in the apprehension and conviction of the others.” Sparing the lives of Dasch and Burger, it was reasoned, might encourage other potential enemy saboteurs to undermine the efforts of colleagues in order to receive leniency.

On August 8, for three hours, one after another of the convicted saboteurs took their seat on the electric chair. Three days later, they were buried in pine boxes in Potters Field, Blue Pains. D.C.

Bodies of the executed saboteurs being taken by ambulance to the Walter Reed Hospital morgue.

Louis Fischer, in his book Nazi Saboteurs on Trial, reports a story about Hitler’s reaction to the failed sabotage scheme. He supposedly yelled at his intelligence chiefs: “Why didn’t you take Jews for that?” The most likely interpretation of Hitler’s outburst, Fisher believed, is that despite his hatred for Jews, he admired their “intelligence and competence.” It is perhaps telling that after the failure of “Operation Pastorius,” Jews began to be hired for jobs in the German Intelligence Service.

In 1948, Attorney General Tom Clark recommended to President Truman that Dasch and Burger have the remainders of their sentences commuted and be sent back to Germany. The two men were taken by Army transport to the American Zone.