In 1741, English colonists in New York City felt anxious. They worried about Spanish and French plans to gain control of North America. They felt threatened by a recent influx of Irish immigrants, whose Catholicism might incline them to accept jobs as Spanish spies. And, above all, they feared that the city's growing slave population, now numbering about 20% of the 11,000 residents of Manhattan and increasingly competing with white tradesmen for jobs, might revolt. When a series of thirteen fires broke out in March and April of 1741, English colonists suspected a Negro plot--perhaps one involving poor whites. Much as in Salem a half-century before, hysteria came to colonial America, and soon New York City's jails were filled to overflowing. In the end, despite grave questions about the contours of the suspected conspiracy, thirty-four defendants were executed. Thirteen black men burned at the stake and seventeen more hanged. In addition, four alleged white ringleaders--two men and two women--made trips to New York City's gallows.

"Fire!"

On March 18, 1741, as the coldest New York winter anyone could remembered neared its end, smoke began rising from the roof of the Lieutenant Governor Clarke's mansion inside the stone walls of Fort George, the hilltop fort built in 1626 along the city's harbor that stood as the city's principal protection from foreign invaders. The city's alarm bell rang. Two horse-drawn wagons carrying fire engines set off toward the fort and a brigade formed in the Fort Garden to pass water buckets along to fight the fire. The fire, however, continued to spread. Flames leaped from the Lieutenant Governor's mansion to nearby barracks and a chapel, and then outside the fort, to the Secretary's Office, where an archive of important documents was housed. In the end, it wasn't the fire engines or the bucket brigade that saved the city from an even more devastating fire, but rather a timely rain. Nearly everyone assumed at first that the Fort George fire was an accident, perhaps started by sparks from a fire pot carried by a plumber for soddering.

A week later, another fire broke out, this one belonging to a prominent sea captain. Then, again exactly seven days later, a third fire. A dockside warehouse burned to the ground, along with everything in it. Suspicions mounted: three fires on three consecutive Wednesdays? New Yorkers began talking about arson.

The pace of fires picked up. Three days after the warehouse fire, a cow stable began burning in the East Ward and, even as that fire was being put out, there was "a second cry of fire," this one for a house on the city's West Side. The following day, after a trail of coals were found leading from a house to a nearby haystack, nobody believed the rash of fires was an accident. On Monday April 6, four new fires broke out. In the case of one of the fires, a disgruntled "Spanish Negro" (one of a group of men seized by the English after an attack on a Spanish ship, and then auctioned off as slaves in New York) came under strong suspicion. Soon the cry of "Take up the Spanish Negroes!" reverberated from street to street. Vigilantes soon succeeded in rounding up five "Spanish Negroes" and hauling them down to City Hall. The interrogation had barely begun when the fire alarm rang again, this time to signal a fire at another warehouse. A Dutch firefighter spotted a black slave named Cuffee fleeing the scene. As a mob described as "upwards of a thousand men" chased Cuffee, a new chant went up in the streets of New York City: "The Negroes are rising!"

The round-up of blacks continued with renewed energy. Many Negroes unfortunate enough to be out on the streets of New York found themselves soon sitting in jail under suspicion for arson. In City Hall, with smoke visible from the windows, City Recorder Daniel Horsmanden and city magistrates questioned the Spanish Negroes and the captured slaves. Meanwhile, Lieutenant Governor Clarke ordered the militia to patrol the city from dusk to dawn, a watch that would continue for the next three months.

Five days later, the Common Council posted notice of a 100-pound reward and a pardon for anyone who would identify persons "concerned in setting fire to any dwelling house or store house." The Council also voted to send out search parties who would search virtually all buildings in the city and stop anyone carrying "bags or bundles." The search turned up little of value to the investigation.

Court Convenes

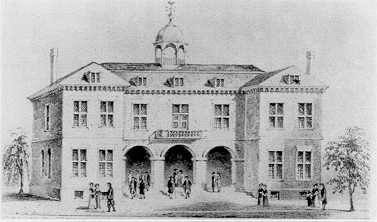

At ten o'clock on April 21, The Supreme Court of Judicature of the Province of New York convened at City Hall, at the corner of Wall and Broad streets. Justice Phillipse began the proceedings by commanding the sheriff to impanel a grand jury. Seventeen men stood up to be sworn as grand jurors, including some (such as a man whose warehouse had recently burned to the ground) whose impartiality might easily be questioned. "My charge, gentleman," Phillipse told the jurors, is "to present all conspiracies, combinations, and other treasons down to trespasses" that related to "the many frights and terrors which the good people of this city have of late been put into, by repeated and unusual fires."

The first person summoned to appear before the grand jury was Mary Burton, the sixteen-year-old servant of tavern owner John Hughson. She was a reluctant witness, and not until she was being led to City Hall's dungeon did she reconsider her initial refusal to testify. Once she began talking, however, she really talked. Burton described a vast conspiracy, including meetings at Hughson's where her master, an Irish prostitute named Peggy Kerry, and two slaves named Prince and Caesar, conspired to burn the Fort and "the whole town." When "white people came to extinguish" the blazes, Burton said, they would "kill and destroy them." When all was done, Caesar would become Governor and Hughson "should be King." Needless to say, Burton's testimony created quite a stir. Justices of the Supreme Court called together all the leading members of New York's bar to consider how and where to conduct prosecutions of slaves. The group decided that the trials should be in municipal sessions court "under the care of the Supreme Court."

Justice Horsmanden assumed the role of principal investigator into the conspiracy. When suspects were rounded up, he would question them himself before turning them over to the grand jury. By modern standards, of course, it would be a clear violation of due process for a judge in a case to conduct an initial investigation, especially when the defendants had no lawyers, but in the early eighteenth century, no such restrictions existed.

On May 1, slaves Caesar and Price faced trial on charges unconnected with the fires. Both men had been charged with the theft of Spanish pieces of eight from a shop owned by Robert and Rebecca Hogg. After hearing from prosecution witnesses including the Hoggs and a white sailor who had participated in the theft and then betrayed the two slaves, the jury returned quick convictions. The Hughsons, who seem to have run a sort of fence operation out of their tavern, and Peggy Kerry were scheduled to face trial the next day on charges of receiving the stolen property. Before the second trial began, however, an indentured servant named Arthur Price (not to be confused with the accused slave also named Price) being held in the jail on robbery charges revealed to Judge Horsmanden that Peggy Kerry had told him that the Hughsons were involved in the arson conspiracy, as well as Prince, Caesar, and two other slaves, Cuffee and Bastian. Sensing the value of his jail house snitch, Justice Horsmanden arranged for Arthur Price to placed in the same cell as Cuffee and for them to be given "a tankard of punch now and then, in order to clear up their spirits, and make them more sociable." The plan worked, and within a day Horsmanden had the name of the Fort George arsonist, a slave named Quack. As Jill Lepore writes in her book New York Burning, "from the prosecutor's point of view, Price was priceless."

The cascade of accusations and confessions continued. On May 9, Peggy Kerry admitted knowing about the arson plot and began naming the names of slaves who, she claimed, played more active roles. Two days later a horse-drawn cart took Kerry's boyfriend and the father of the child she carried, Caesar, and Price to specially erected gallows on a small hill at the edge of the city. Both men died without confessing, the first victims of a long and grisly summer of executions. After the hanging, Caesar's corpse was removed and gibbeted, and then placed on display to, in the words of Daniel Horsmanden, serve as an "example" and to induce others "to unfold this mystery of iniquity."

Whether to end beatings or beat death sentences, accused slaves pointed fingers at other slaves. In return for a promise that his own life would be spared, a slave named Sandy identified fifteen blacks, including four "Spanish Negroes," as plotters. One of the slaves fingered by Sandy, a slave named Fortune, in turn testified before the grand jury that Quack told him two days before the Fort George fire "that the fort would be burnt." Fortune also testified that Cuffee was involved in one of the warehouse fires.

Quack and Cuffee Trial

The trial of King v Quack and Cuffee would be the next trial in the series. Attorney General Richard Bradley delivered the government's opening statement, accusing Quack and Cuffee of committing a crime "so cruel and detestable...that one would think could never have entered into the minds of any but a conclave of devils." The prosecution case that followed consisted of eleven witnesses. Mary Burton testified first, stating that the defendants hatched the arson plot at Hughson's. Following Burton, the slaves Fortune and Sandy repeated the testimony they had previously given in the grand jury proceedings. Sandy stated that Quack had told him, after the burning of the fort, "The business is done." Cuffee, meanwhile, had announced his intention to "set fire to the town" even if it meant his own hanging or burning. (In colonial New York, slave evidence was admissible, but only against other slaves, and only in cases involving murder, arson, and conspiracy.) Except for Arthur Price, and his testimony concerning Cuffee's alleged jail cell confession, the remaining witnesses (all white) provided far less damning evidence. Quack and Cuffee, forced to conduct their own defense, called ten witnesses, who mostly presented alibi evidence. William Smith offered the government's closing argument. Smith claimed that the evidence proved Quack and Cuffee participated in a conspiracy to "establish themselves in peace and freedom in the plundered wealth of their slaughtered masters." The jury quickly returned its verdict: Guilty as charged. Justice Horsmanden pronounced sentence: "You shall be chained to a stake, and burnt to death." On May 30, a large crowd watched as the two convicted slaves were chained to two tall wooden poles surrounded by piles of wood. Both men offered hasty confessions in the hopes that they might be spared a painful death. Cuffee admitted starting the storehouse fire with lighted charcoal, while Quack said he placed "a lighted stick" between the shingles and the roof of Clarke's Fort George mansion. In addition, Quack and Cuffee identified John Hughson as "the first contriver" of the plot and provided names of other conspirators. Despite the last-minute confessions, there would be no reprieve. The piles were lit.

Hughson Trial

Authorities seemed of the view that no conspiracy as broad as the one recently endured by New York could come solely from the minds of slaves. After Quack's and Cuffee's confessions at the stake, they settled on tavern owner John Hughson as the chief author of the plot. The trial of Hughson, his wife Sarah, their daughter, and Peggy Kerry brought a standing-room-only crowd to City Hall on June 4. The trial spectators witnesses followed different rules than the two previous plot trials because, as whites, the defendants were entitled under New York law to more protections. Granted twenty peremptory challenges of potential jurors, the defendants used them all--including one against, it seems, a favorite client of Peggy Kerry's.

In his opening statement, Attorney General Bradley savagely attacked the "infamous Hughson": "Gentlemen, this is that Hughson whose name and most detestable conspiracies will no doubt be had in everlasting remembrance...This is the man! This is the grand incendiary!--that arch rebel against God, his king, and his country!--that devil incarnate, the chief agent of the old Abbadon of the infernal pit, and Geryon of darkness."

Limited by law to presenting white witnesses, the prosecution first called two officials who witnessed the last-minute confessions and statements of Cuffee and Quack. (Fortunately for the prosecution, the dying confessions of blacks--although not their testimony while living--was admissible.) White servants Mary Burton and Arthur Price also testified. Burton told jurors she had witnessed at Hughson's tavern numerous gatherings, usually on Sundays, of twenty to thirty Negroes. Among those frequently present, she said, were Caesar, Prince, Cuffee, and other slaves accused of arson. Burton testified that Hughson provided Negroes with guns and conspired with them to "burn the whole town" and "cut their masters' and their mistresses' throats." When this was done, Burton said, "Hughson was to be king, and Caesar governor." During Burton's testimony, according to Daniel Horsmanden's trial account, the prisoners "threw up their hands and cast up their eyes, as if astonished."

John Hughson conducted the defense for all four defendants. None of the four defense witnesses offered especially compelling testimony. For example, a lodger at Hughson's named Eleanor Ryan testified that she never saw large groups of Negroes at Hughson's and certainly "never saw any entertainments there for Negroes." On the other hand, Eleanor Ryan's testimony was undoubtedly more helpful to the defense than that of another defense witness, Adam King, who claimed to have seen "whole companies of Negroes playing dice" at Hughson's.

Unsurprisingly, especially in view of Justice Horsmanden's urging that they do so, the jury returned a verdict of guilty for all defendants. Upon sentencing the four to death by hanging, Justice Philipse expressed amazement at the dastardly plot that had been uncovered: "...To encourage these black seed of Cain to burn the city and to kill and destroy us all--Good God!" On June 12, John and Sarah Hughson and Peggy Kerry (the execution of Hughson's daughter was postponed) were hanged. To the disappointment of officials, none of the three confessed.

Jack's Confession and the Real Plot

The parade of defendants to the City Hall courtroom accelerated. After a three-day trial in early June, six more blacks were convicted and sentenced to die in connection with the arson plot. One of the condemned six, a slave named Jack, offered to tell judges all he knew of the conspiracy if only his life could be spared. Jack's confession, described a large meeting of Negroes in February in the home of his master, Gerardus Comfort. Somewhat troubling to authorities was the fact that Jack placed the start of the conspiracy at the home of Comfort, while Mary Burton testified that the conspiracy had its origins at Hughson's, Comfort's next-door neighbor. Still, they considered Jack's confession a godsend. Particularly helpful to the prosecution was Jack's willingness to name each Negro present and to state exactly what each agreed to do to further the conspiracy. For example, Jack said, York complained that his master had "scolded at him and he would kill her." Cato, he told judges, "said he would get his master's sword and then set the house on fire." Another round up began, and soon seven more suspects could contemplate their bleak futures in the discomfort of the City Hall dungeon. Jack, meanwhile, received a pardon.

Confessions, accusations, arrests, convictions, and executions continued as the summer warmed. By the end of June, over a hundred slaves sat in New York's jail. Some people began to worry that blacks were making false confessions and accusing the innocent in order to gain pardons and save their own lives. Daniel Horsmanden, recorder of the confessions, remained convinced that the confessions were genuine: "Could these be dreams, or is it more rational to conclude, from what has happened amongst us, that they were founded on realities?" The latter, he concluded--but when slaves burned maintaining to the end their innocence, others grew doubtful.

What really happened in New York in 1741 will never be entirely clear, and many of the condemned were probably without guilt, but there was a real plot and it did involve slaves. Although the biases of authorities led them to suspect that whites must have been the masterminds of such an extensive and diabolical plot, that most likely was not the case. The plot was probably more Jack's than Hughson's, argues historian Jill Lepore. She notes that other slaves put Jack at the center of the plot. A slave named Sandy, for example, told the grand jury that one day in February, as he was walking past Comfort's house, Jack invited him into the home. Inside, he found "about twenty Negroes." "They gave me a drink," Sandy is reported to have testified, "and then asked me to burn houses." Lepore believes that Jack was member of New York's Akan-speaking community. (Akans were an ethnic group from Ghana.) She attaches significance to the fact that while Akan speakers represented only 4% of New York's slave population, there were nearly 40% of those burned at the stake. Lepore also notes that "much of the plotting to which slaves confessed in 1741 bears considerable resemblance to ceremonies known to have taken place among the Akan-influenced communities of the New World." While Jack and others plotted, Lepore contends, the feast for Negroes at Hughson's was "essentially a prank that grew out of proportion," a ceremony intended as a mockery of Masonic initiations practiced by many of the city's leading white citizens.

The motive behind the conspiracy?--for most slaves, it was a simple desire for liberty. According to testimony concerning the meeting of slaves at Comfort's house, a slave named Ben pointed to denials of basic freedom as the justification for arson: "[We] could not so much as take a walk after church-out, but that the constables took [us] up; ...in order to be free, [we] must set the houses on fire and kill all the white people." For Quack, whose fire-setting at Fort George started it all, motivation came from the Governor's decision to deny him the right to spend occasional nights with his wife at the fort, where she served as a slave.

Some slaves saw hope for liberty in the ongoing war between England and Spain, and English authorities worried that "Spanish Negroes" might, of allegiance with Spain, be only too happy to join in a conspiracy aimed at the many English settlers in New York City. It is hardly surprising, therefore, that a number of Spanish slaves found themselves on trial for conspiracy in the summer of 1741. On June 17, five accused Spanish slaves (originally claimed as prizes when they were seized by the English on a Spanish ship) listened (with the aid of an interpreter) as five prosecution witnesses accused them of involvement in the arson plot. The fact that the prosecution witnesses understood little or no Spanish raised, even in the minds of hardened judges, some credibility questions. In their own defense, the Spanish offered alibi evidence and argued that by law they should be free men, not slaves, and thus should be entitled to all the procedural protections of white citizens. Despite the very weak evidence of guilt, the jury returned all defendants guilty after only thirty minutes of deliberation. The verdicts in the "Spanish Negroes" trial marked perhaps the clearest example yet of injustice. As Jill Lepore writes: "What Spain promised [freedom for slaves that deserted English colonies] led New York slaves to seek alliance with "Spanish Negroes," and later to betray them in confessions, but there is little evidence that Spanish slaves joined either "Hughson's Plot" or the "Negro Plot."

Trial of the "Priest," John Ury

By mid-summer, Lieutenant Governor Clarke concluded that the conspiracy trials were getting out of hand. In June he wrote to London, "I desired the Judges to single out only a few of the most notorious for execution, and that I would pardon the rest." In late June, the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, James DeLancey returned from overseas to meet with his fellow justices who had been conducting the plot trials. The meeting came at a time when some slaves were recanting confessions and "Negro Evidence" was rapidly losing its credibility. Chief Justice DeLancey might well have reminded the other judges that wholesale executions of slaves were costing city slaveholders their valuable property. DeLancey, in his first significant act in the proceedings, announced the pardon of forty-two accused blacks. Under his plan, the slaves would be boarded on ships and sold as slaves in foreign lands, with the owners of the slaves receiving the proceeds of the slave sales. A trial on July 15, which resulted in the conviction of eight black men, would be the last of the slave trials.

Still, one more trial remained. Confessing slaves had made reference to a short white man who had the power to forgive their sins, a man that authorities immediately assumed must be a priest. On June 24, constables found their suspected priest, a recent arrival in the city named John Ury. Court records note that Ury came to the city "pretending to teach Greek and Latin." (Simply being a Catholic priest was, in New York City in 1741, a crime punishable by death.) Mary Burton, asked if she could identify Ury, told investigating judge Horsmanden that she had "often seen" Ury in John Hughson's home.

Later, contradicting an earlier statement, Burton claimed to have witnessed an Irish soldier named William Kane discussing the arson plot with Hughson. Kane surprised authorities with a confession that seemed to suggest a whole new plot, one that had little to do with those considered in earlier trials. According to Kane, a group of conspiring clandestine Catholics planned "to burn the English Church," as well as what they could of the city, and then take what goods and riches they could and distribute them among the city's poor. Kane identified Ury, "who acted as a priest," as one of the plotters.

On the opening day of John Ury's trial, July 29, Attorney General Bradley told jurors that Ury "with a cross in his hand" swore black men into Hughson's plot. He promised the men, Bradley said, to forgive their sins. Bradley claimed Ury believed that it was justified to "kill and destroy" all those that do not share what Bradley described as "their detestable religion," their "hocus pocus, bloody religion."

The prosecution presented three key witnesses. Mary Burton testified concerning Ury's promise of forgiveness to plotters and his alleged conducting some sort of ritual that included "a black thing like a baby on a table" and his reading from a book. William Kane testified that Ury tried to convert him into Catholicism and, one night at Hughson's swore him into the plot. Sarah Hughson, the convicted daughter of John Hughson, and who had received a pardon only minutes before Ury's trial began, testified that Ury had encouraged slaves to burn the city and promised that, if they did, he could pardon their sins.

Ury conducted his own defense. He produced witnesses who testified he was just what he claimed to be, a school teacher in ancient languages. He tried to show that he was a dissenter from Anglican Church teachings, but not a papist. In a statement he read to the jury, Ury suggested he would have to have been a "lunatic" to have organized a massive arson plot and then remained in the city as the investigation went on for months afterwards.

When the nine-hour trial ended, the twelve jurors withdrew to deliberate. Fifteen minutes later they came back with their verdict of "Guilty." On August 29, Ury offered his last words before he was hanged: "[Death] is the cup that my Heavenly Father has put into my hand, and I drink it with pleasure."

Epilogue

Justice Horsmanden's edited account of the trials is our principal source of information for the 1741 arson conspiracy.

With the conviction of John Ury, Justice Horsmanden felt happy that the investigation into the 1741 conspiracy had finally reached "the bottom." In his view, all the plots before Ury's were subplots, all folded under the priest's large umbrella conspiracy. On September 24, New York City celebrated "a Day of Thanksgiving" for the "deliverance from the destruction threatened by the late conspiracy."

Unhappily, from Horsmanden's point of view, there was in the land a growing chorus of skeptics, fueled by more recantations from prosecution witnesses and revelations that Mary Burton had told some obvious lies during the course of her interrogation. A rare surviving letter from one trial critic suggested that the New York trials brought to mind the discredit witch trials in Salem a half-century earlier.

To deal with such critics, Horsmanden took on the task of preparing for publication an edited account of the 1741 trials. In the spring of 1744, Horsmanden's Journal finally was published. It sold poorly; there were new concerns in the city. Today it survives as one of the most complete trial accounts of America's colonial period.