The “Reign of Terror” that overtook the Osage Reservation in 1921 is just one chapter in the long story of mistreatment of Native Americans by whites—but is one of the most horrifying. Before the chapter ends, untold dozens of Osage tribal members (and those who dared support them) are murdered. Many are poisoned, others blown up as they sleep in their homes, shot in the head, thrown off moving trains, or killed in other gruesome ways. And it’s all for money. In the end, there will be a series of trials from 1926 to 1929. Some of the murderers will pay a price for their evil, but many others will escape prosecution.

Background

As was so often the case for Native Americans, the Osage were forced to cede their ancestral lands—lands between the Missouri and Arkansas Rivers. First moved to a reservation in Kansas, the Osage in 1870 sold their Kansas lands for $1.25 an acre to settlers and were driven to land in northeastern Oklahoma that, until 1866, had belonged to the Cherokee. The reservation encompasses all of Osage County, about a million and a half acres. Unsurprisingly, the reservation land in Oklahoma is hilly, thickly wooded in places, and was deemed at the time largely unsuitable for most agricultural purposes.

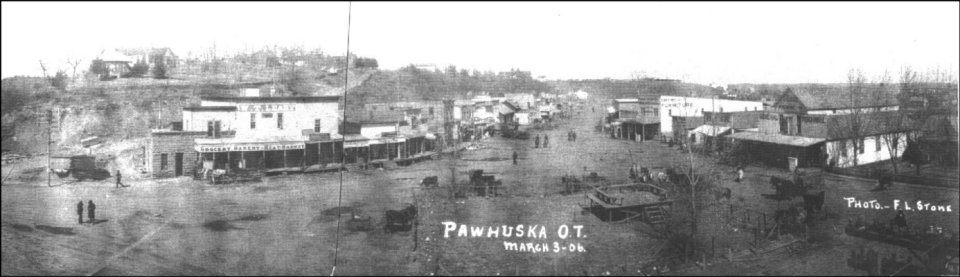

Pawhuska, Osage Nation, Oklahoma (1906)

But not for all purposes. Oil was discovered on the Osage reservation—lots of oil. And the Osage Act of 1906 had given each of the 2,229 members of the tribe “headrights” for money received for the production of oil on reservation land. As the oil production boomed, the Osage became rich. Net per capita distribution of funds from oil rose from $221 in 1915 to $12,400 in 1923 (roughly comparable to $200,000 today), the year of the murders that will lead to the trials of 1926 to 1929.

The enormous wealth of the Osage attracted criminal elements and unscrupulous traders and business people. The notorious Al Spencer gang of bank robbers hid out in Osage County. Gangs of bootleggers operated a privately owned power plant and used the county as a distribution center. Dozens of bank and train robbers even held a convention of sorts in Osage County in the free-wheeling 1920s. But the biggest game around was taking money from the wealthy Osage, by overcharging for goods and services, by fraud, or by murders that might enable the murderer to acquire money either through insurance or (for those whites who married into Indian families) gaining greater shares of the valuable head rights. We will never know exactly how many Osage died for their money. Osage historian Louis Burns said, “I don’t know of a single Osage family that didn’t lose at least one family member because of head rights.” A federal agent who investigated the reign of terror on the reservation said, “There are so many of these murder cases. There are hundreds and hundreds.”

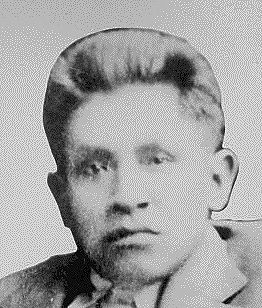

Charles Whitehorn

The killing began in earnest in1921. Charles Whitehorn, a full-blooded Osage, was last seen alive on May 14. Two weeks later his body was discovered on a hill about a mile from downtown Pawhuska. Whitehorn had been shot twice between the eyes. After Whitehorn’s murder, his widow Hattie married a disreputable white man named LeRoy Smitherman. Investigators would later conclude that the murder was orchestrated for Charles’s valuable head rights by Hattie, Smitherman, and a boarding house operator in Pawhuska named Minnie Savage, but no one would ever be prosecuted. Hattie told an investigating agent, “If I tell you [what happened], you will send me to the electric chair.” And so she said nothing and escaped punishment, like most of the Osage murderers.

This account will focus largely on the murders that did result in prosecutions. Five murders in particular: The May 22, 1921 shooting of Anna Brown, the February 6, 1923 shooting of Henry Roan, and the March 10, 1923 explosion that took the lives of Bill and Rita Smith, as well as their servant, Nettie Brookshire.

The Murder of Anna Brown

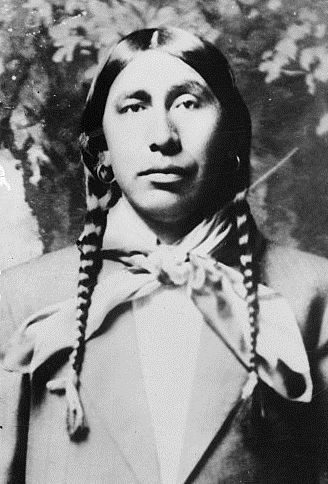

Anna Brown, age 34, was a registered member of the Osage tribe and one of four daughters of Lizzie Q. Her sister Minnie had died three years earlier of what doctors called "a peculiar wasting illness." Minnie was just 27 when she died--and had been in excellent health until the onset of her confounding disease. Anna was the wildest of the three sisters. She had divorced her husband, Oda Brown, and taken to drinking, dancing, and carousing with friends until the sun rose. According to her servants, Anna had "very loose morals with white men."

On May 21, 1923, Anna--at the urging of her younger sister Mollie--came to Gray Horse to take care of her bedridden mother. But Anna was drunk on bootleg whiskey and things did not go well. After she sobered up a bit and had a bite to eat, Bryan Burkhart, the younger brother of Mollie's husband Ernest, offered to drop Anna off at her home. Anna said goodbye to Mollie and headed out the door with Bryan. It was the last time Mollie ever saw her sister.

Anna Brown (left), with her mother, Lizzie, and her sister, Mollie

A week later, a boy who was squirrel hunting near a ravine north of the town of Fairfax found a rotting corpse. The gold fillings and the blanket meant it had to be the body of Anna Brown. Two local doctors, James and David Shoun, performed an autopsy. The autopsy revealed Anna had been dead for about a week and that she had been shot in the head with a .32-caliber bullet.

Mollie had, she thought, a powerful ally in support for her quest for justice for the murder of her sister Anna, William Hale. Hale was the uncle of her husband Ernest and his brother, Bryan. Called "King of the Osage Hills," Hale was wealthy, powerful, and well-connected. He was a neat dresser with a ruddy complexion and "a self-confident and military air." He signed his letters "Rev. W. K. Hale" and called himself a "true friend" of the Osages. He donated money to schools and hospitals, acted as a deputy sheriff in Fairfax, owned 45,000 acres of prime grazing land, and recited poetry to boot. He controlled a Fairfax bank and owned a stable of fine horses. Hale told Mollie he would help find Anna's killer. He described Anna as a "mighty good friend."

William K. Hale

A coroner's inquest into Anna's murder provided few answers. Bryan Burkhart told inquest jurors that he had dropped Anna off at her house on the day of her murder around "5 or 4:30" and never saw her afterwards. Some suspected Anna's murderer came from off the reservation, while others considered her ex-husband, Oda Brown, to be the prime suspect. But prosecutors had little solid evidence. Mollie's family offered a $2000 reward for information leading to the arrest of Anna's killer, but still no one stepped forward. Hale also promised his own rewards, both for the killer of Anna and the killer of Charles Whitehorn, saying "We've got to stop this bloody business."

Meanwhile, Lizzie got weaker and weaker--from what many assumed to be the same strange wasting disease that claimed the life of her daughter, Minnie. Lizzie died in July. Mollie's brother-in-law, Bill Smith, suspected that Lizzie's death had nothing to do with a peculiar disease. He believed she was poisoned--and that Lizzie's death, as well as Minnie's and Anna's, had a lot to do with the valuable headright in Osage oil that her family claimed. No one could buy or sell headrights. But they could be inherited.

As detectives continued their investigations, other Osage members died under suspicious circumstances. William Stepson, a 21-year-old champion steer roper, fell into convulsions and suffocated--both classic indications of strychnine poisoning. A month later, an Osage woman died of what was also believed to be a poisoning. In August 1922, Barney McBride --a wealthy oilman trusted by the Osage--traveled to Washington DC to urge a federal investigation of the string of murders in Oklahoma. After an evening playing billiards in the capital, McBride stepped outside the club where someone tied a burlap sack around his head and then stabbed him over twenty times. McBride's murder attracted national attention. A headline in the Washington Post stated what was becoming obvious to many in Oklahoma: CONSPIRACY BELIEVED TO KILL RICH INDIANS.

The Murder of Henry Roan

In February 1923, two men out hunting spotted a car down a steep slope northwest of the town of Fairfax, Oklahoma. The hunters reported their discovery to local authorities who found in the car the body of a man slumped behind the steering wheel. He had been shot in the back of the head. The victim was 40-year-old Henry Roan. Roan was married and the father of two children. J. Edgar Hoover later described Roan as "a picturesque, full-blood Osage Indian, six-foot tall and a fine looking specimen."

Henry Roan

Bill Hale, of course, was one of the first to be told by authorities of Roan's murder. The mayor of Fairfax said Roan "considered W. K. Hale his best friend." At Roan's well-attended funeral, where Osage elders sang their traditional death songs, Hale served as a pallbearer. Only a couple of weeks before Roan's murder, Hale had visited Roan and attempted to help him deal with his recent discovery that his wife was having an affair with a man named Roy Bunch. Could Bunch have been the murderer? Hale suggested that he should at least be considered a suspect. Hale, meanwhile, had to be thinking about the $25,000 he would soon receive, having been listed as Roan's beneficiary on his life insurance policy.

With Roan's death, the level of fear among the Osage reached new heights. They lighted their homes against the darkness and wondered who would be next. Among the worried were Bill and Rita Smith, who decided to leave their isolated home in the country in favor of the relative safety of a new home in Fairfax. Like many Osage, the Smiths kept a dog as a measure of protection. But in March of 1923, dogs around their neighborhood began to die--poisoned.

The Murders of Bill and Rita Smith and Nettie Brookshire

Bill Smith had been one of the most outspoken Osage in demanding that murders be tracked down. When he appeared before the Tribal Council to call for justice, some Osage suggested that an "evil spirit" was stalking their community. "No!" said Smith. "There is no evil spirit except one in human form." When some in the crowd asked him to name the murderer, Smith remained silent. To name the killer or killers would be a virtual death sentence.

On March 9, after checking out an investigative lead into Roan's murder with a friend, Bill Smith drove his Studebaker back to his home in Fairfax. His wife, Rita, was waiting for him. Their white servant, seventeen-year-old Nettie Brookshire, was also spending the night at the Smith home. At 2:50 in the morning, a loud explosion blew the Smith home to smithereens. Rita and Nettie died almost instantly, but--miraculously--Bill Smith managed to survive for several days, even though burned almost beyond recognition. Hovering near death, Smith would cry out, "They got Rita and now it looks as though they've got me."

What's left of the Smith house after the March 10, 1923 explosion

After the Smith murders, the Tribal Chieftain said: "We must appeal to the white father in Washington. Our people, once peaceful and happy, are afraid for their lives....No one knows when he will be called to the Happy Hunting Grounds." The Tribal Council adopted a resolution asking "the Honorable Secretary of the Interior be requested to obtain the services of the Department of Justice in capturing and prosecuting the murderers of the members of the Osage Tribe."

The Investigation

The explosion lent even more urgency to the search to find the killers, but many Osage saw corruption everywhere and didn't know who to trust. One local attorney and former prosecutor, W. V. Vaughan, tried as best he could to solve the crimes. In June 1923, Vaughan received word that an Osage member named George Bigheart had information about the murders but was dying of a suspected poisoning in an Oklahoma City hospital. (Not coincidentally, most likely, Bigheart had been seen with Hale shortly before Bigheart began failing and was taken to the hospital.) The only person Bigheart would share his information with was Vaughan--he trusted no one else. So Vaughan rushed to Oklahoma City to meet with Bigheart. After Bigheart died in his company, Vaughan phoned the sheriff of Osage County to report he had new critically important information about the series of Osage killings and that he was leaving on the first train. Thirty-six hours later, Vaughan's body was discovered lying near railroad tracks north of Oklahoma City. He had been stripped, his neck broken, and thrown off the train.

In the summer of 1925, the new boss man at the Bureau of Investigation (later to be better known as the FBI), thirty-year-old J. Edgar Hoover, summoned Tom White, head of the Bureau's Houston office, to Washington. White had a reputation for competence and straight-shooting--and Hoover had an important job for him. He asked him to direct the Bureau's investigation, which had begun in 1923, into the Osage murders. Hoover called the situation "acute and delicate." The job meant moving his family to Oklahoma City, to head up the field office there, and would--given recent history--put him at significant personal risk of death or injury. But White told Hoover, "I am human enough and ambitious enough to want" the job.

Tom White and J. Edgar Hoover

When White took over the investigation, he poured through voluminous records on the case. Agents had concentrated on the cases they considered most likely to be solved and prosecuted--specifically, the bombing deaths of Bill and Rita Smith and their servant, and the shootings of Henry Roan, Anna Brown, and Charles Whitehorn. The investigation had been difficult. As might be expected, almost anyone who knew anything was reluctant to talk, fearing that they might be the killers' next victim. With the exception of White, almost all agents operated undercover as an insurance salesman, a "medicine man,".a cattleman, and a prospector. In a 1953 history of the Osage murder cases, the Bureau describes "the general class of the citizenry in the territory" as "very low. The rich oil fields produced not only an abundance of oil, but also graft, easy money, gambling, prostitution, whisky and parasites bent on the milking the Indian out of all he owned." According to the FBI report, Osage distrust of whites was "almost universal" and "agents had to rebuild their confidence in law enforcement."

The investigation into the murder of Anna Brown raised questions before it produced answers. Why, if there was no exit wound in the front of Anna's skull, was no bullet found at the autopsy? Could the examining doctors, David and James Shoun, have taken it? What about the report by a Kaw Indian woman that Rose Osage had Anna killed because she tried to seduce his boyfriend? But Rose Osage's alibi checked out and the Kaw Indian's story didn't add up. Why would she lie to investigators? Is she being paid to protect the real killer?

The first significant break in the Anna Brown case came when an elderly farmer told agents he had seen Anna on the night of her murder. She was sitting inside a car that stopped by a hotel in Ralston. She said hello to someone in his group. The farmer's wife added critical information. The man driving the car was Bryan Burkhart. When they pulled away from the curb, she said, Burkhart headed "straight west from there." Burkhart, agents knew, had said he had dropped Anna off at her home around "5 or 4:30" and never saw her after that alive. If the farm couple were right, then Burkhart was lying. Gathering information from other sources, the agents began to create a timeline that put Burkhart and Anna, and an unidentified "third man," at a speakeasy until about 1:00 a.m. Another witness reported seeing Bryan shouting at Anna around 3:00 a.m., saying "Stop your foolishness, Annie, and get into this car." Bryan Burkhart was not seen again until about sunrise, when he finally returned home.

Bryan Burkhart

Another break in the investigation came when a private eye, supposedly hired by W. K. Hale, found himself arrested for robbery in Tulsa. The "private eye" revealed to agents that he had actually been hired by Hale to "shape an alibi" by producing witnesses willing to lie. He offered another useful piece of information. He said that when he met with Hale and Bryan Burkhart to discuss his muddying-the-waters campaign, Ernest Burkhart was often present as well.

Tom White interviewed people who had been in the hospital room with Bill Smith in the four days before he died of injuries from the explosion. No one he talked to said Smith actually named his murderers, but Smith's lawyer reported that Smith had told him as Smith lay in his hospital bed: "You know, I only had two enemies in the world," Hale and Ernest Burkhart. In addition, Smith's nurse revealed she had been visited by Hale, and that Hale asked her whether Smith had named his likely killers.

White saw in the $25,000 insurance policy held by Hale for Henry Roan's life a possible key clue to that murder. The policy provided an obvious motive. An insurance salesman told agents that Hale's story that Roan insisted on making Hale, a close friend, his beneficiary was not true. In fact, the salesman said, Hale had asked for the policy. "Hells bells, that's just like spearing fish in a keg," Hale had told him. Further investigation revealed that Hale had to shop around for a doctor who would approve Roan for the policy. Many doctors would balk at approving a man with a history of heavy drinking and a prior driving accident while intoxicated. But Dr. James Shoun was willing to authorize the medical approval. White found another interesting connection between Hale and Roan. Hale had previously attempted to purchase Roan's headright, but the transaction never occurred after an expected change in the law allowing such sales failed to pass.

White also began to piece together a thread linking the Brown and Smith murders. With Anna, unwed and without children, being the first victim, her headright passed to her still-living mother, Lizzie. Then Lizzie's death, probably through poisoning, meant that her headright passed to her two surviving daughters, Rita and Mollie. If Rita and Bill were to be killed simultaneously, as they almost were in the explosion, the headrights for them would pass entirely to the last remaining sister, Mollie. And Mollie, of course, was married to Ernest Burkhart, Hale's nephew. White wondered whether Ernest's marriage to Mollie in 1919 might actually have been the first step in a long and murderous plot.

Ernest Burkhart and Mollie

An informer told White the name of the "soup man," the explosives expert who designed the bomb that blew up the Smith house. The man's name was Asa Kirby. But Kirby was dead, and it seemed, Kirby's death was also Hale's doing--another potential witness disposed of. Kirby had been killed when he attempted to rob diamonds from a jewelry store. The shopkeeper had been informed by William Hale about the planned robbery and was waiting with a shotgun when Kirby showed up. In turned out, Hale even had set up the robbery, telling Kirby about the stash of diamonds and suggesting the perfect time to rob them. Not so perfect for Kirby.

In the fall of 1925, Mollie revealed to a priest that she believed someone was trying to poison her. Mollie had been getting injections of what she assumed was insulin from the Shoun brothers, but her condition was worsening, not improving. White and other agents found her illness to be "very suspicious" and arranged to have her taken to a hospital for treatment. Once she was no longer receiving "insulin injections" from the brothers Shoun, her condition improved markedly. An agent's report stated, "It is an established fact that when she was removed from the control of Hale and Burkhart, she immediately regained her health." Asked later about the injections he administered to Mollie, James Shoun was evasive. "Weren't you giving her insulin?" a prosecutor asked. "I may have been," Shoun answered.

Mollie's illness, fear and impatience in the Osage community, and other factors convinced the Department of Justice it was time to act. Warrants for the arrest of Hale and Ernest Burkhart for the murders of Bill and Rita Smith and Nettie Brookshire were issued on January 4, 1926. On his way to jail in Guthrie, Oklahoma, Hale refused the opportunity to make a statement to the press about his case other than to say, "I'll not try my case in the newspapers, but in the courts of this country." In Guthrie, White and Agent Frank Smith questioned Burkhart, hoping to secure a confession. They brought to Guthrie an incarcerated outlaw named Blackie Thompson. Thompson told Burkhart that he had revealed to agents that Burkhart had had asked him to kill Bill Smith in return for a new automobile.

Rita Smith and Nettie Brookshire, two of the bombing victims

Later that night, Burkhart decided to talk. Burkhart said he initially objected to the plan to blow up the Smith home. But, he said, he "relied on Uncle Bill's judgement--and Hale pointed out that his wife would get the additional money from the inherited headrights. Burkhart said he tried to get Blackie Thompson to do the job, but when he wouldn't do it, Hale turned to Asa Kirby. "Acie would do it, that's what Hale told me." Burkhart said that shortly before Hale left for Texas he told him to deliver a message to a thief and bootlegger named John Ramsey. The message was that the time had come to pull off the Smith job. As soon as the blast went off, Burkhart said, "I knew what it was." Burkhart also identified Ramsey as the triggerman in the Henry Roan murder. After Burkhart's confession, White sent orders to agents to pick up Ramsey and take him into custody.

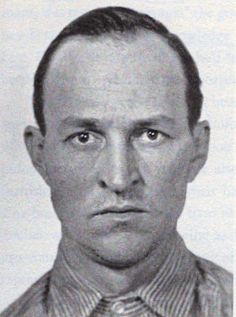

When Ramsey was shown Burkhart's signed statement, he said "I guess it's my neck now. Get your pencils." In his confession, Ramsey admitted to killing Roan--"a little job Hale wanted done." He said he described drinking whiskey with Roan on the running board of his car. The when "the Indian got in his car to leave, I shot him in the back of the head." Ramsey seemed to think of Indians as less than fully human. He told the agents "white people in Oklahoma thought no more of killing an Indian than they did in 1724."

Burkhart, in his statement, refused to implicate his brother Bryan in the murder of Anna Brown, but he did identify the "third man" that had been seen with Anna shortly before her murder. The man turned out to be a person the agents had enlisted to help them in getting to the bottom of the very murder he participated in, Kelsie Morrison. Morrison, according to Burkhart, was Anna's killer. Authorities had yet one more person to bring in for questioning.

Finally, White decided it was time to talk to Hale. White told Hale, "We have unquestioned signed statements implicating you as the principal in the Henry Roan and Smith family murders. We have evidence to convict you." Hale replied, "I'll fight it." And he likely thought he would win that fight. He had money and he had influence.

The Trials

The Department of Justice was well aware of Hale's influence and understood that convicting him in state court would be extremely difficult. So they examined the various murders to see if any might be the basis for a prosecution in federal court rather than state court. Crimes committed on Indian territory provided a basis for federal jurisdiction. On the other hand, crimes committed on lands sold to whites or that were otherwise not under tribal control could only be prosecuted in state court. The Roan case seemed the most promising for federal jurisdiction, as Roan's murder occurred on what was still an Osage allotment. Charges against Hale and Ramsey for the murder of Henry Roan were brought in federal district court in Oklahoma. The prosecution team included U. S. Attorney Roy St. Lewis and John Leahy, a lawyer hired by the Osage Tribal Council. Tom White later described Leahy as a man of "splendid character" and "one of the best attorneys in the state of Oklahoma."

U.S. Attorney Roy St. Lewis

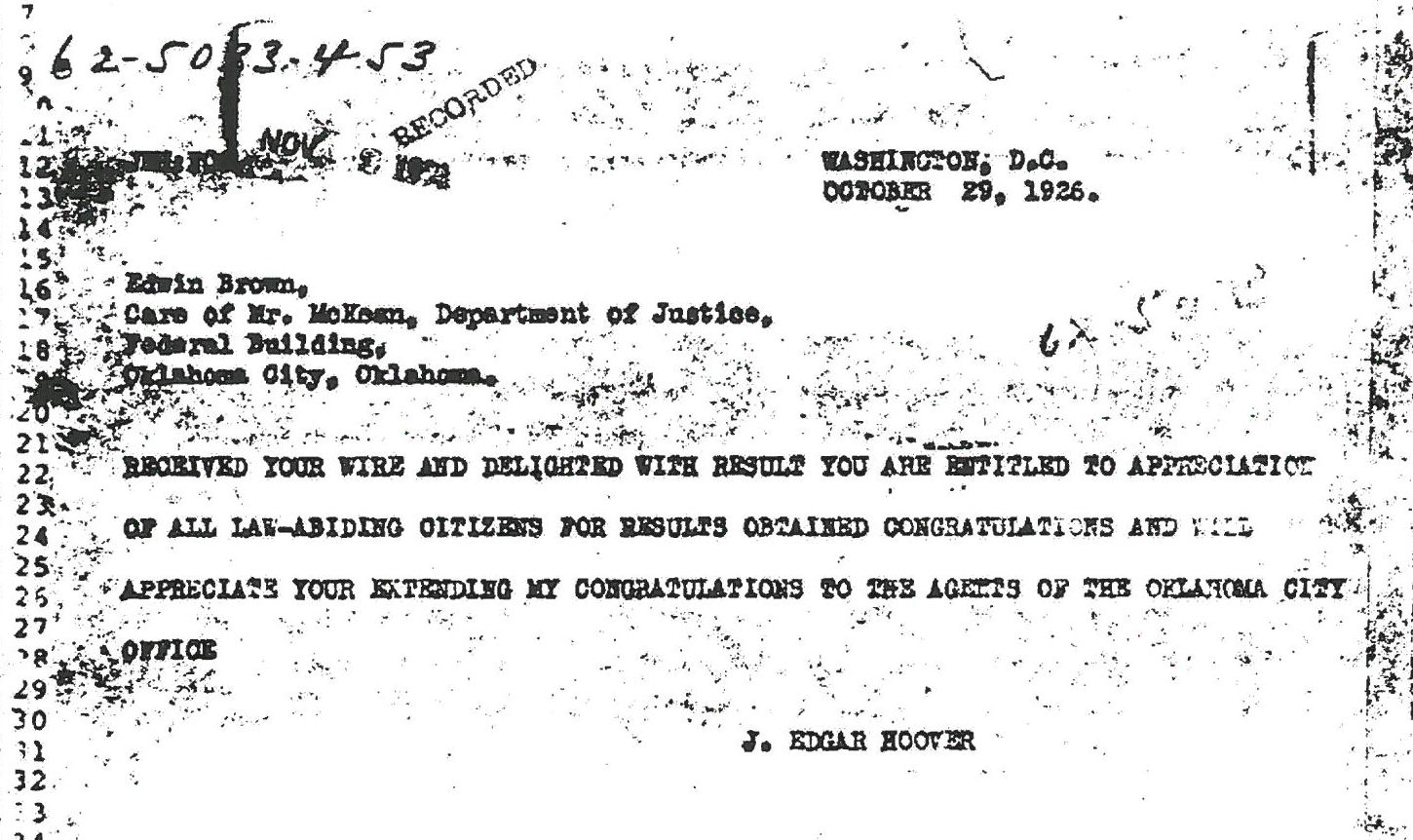

Grand jury proceedings began in early January 1926. The New York Times reported: "Seldom in the long history of the white man's dubious dealings with the Indian has there been such a determined combination of craft and violence as that described by witnesses before the grand jury." The evidence convinced the grand jury to issue the requested indictments.

Hale's chosen lawyer to represent John Ramsey, Jim Springer (a local attorney with a reputation for playing fast and loose), wasted no time in getting his client to recant his confession. "I never killed anyone," Ramsey now declared. Beginning with the grand jury proceedings in January 1926, Springer would try every trick in the book. He and his associates enlisted witnesses to lie, intoxicated witnesses who might incriminate their clients to reduce the value of their testimony, threatened potential hostile witnesses, bribed jurors, and made outrageous claims that had no basis in fact. Springer claimed, for example, that the statements signed by Burkhart and Ramsey were made only after being subjected to torture by federal agents. (The tactics would so infuriate White and J. Edgar Hoover as to cause them to pressure the Department of Justice to prosecute Springer, as well as defense witnesses who committed perjury.) An FBI account of the case stated, "Hale's lawyers employed every device, legal and illegal, to obtain their client's freedom."

The biggest threat to Hale, as he saw it, was Ernest Burkhart. With justification, Burkhart feared for his life. On January 20, Burkhart told White that he felt he would soon be "bumped off," and White arranged for Burkhart to be transported out of state and guarded until trial. He was registered in hotels under an alias. In a letter to Hoover, White said that while "every precaution is being taken," he worried that someone hired by Hale might "slip poison" to Burkhart.

On March 1, prosecutors received bad news. The trial judge ruled that an Osage allotment is not the same as tribal land, and that the murder trial would have to proceed, if at all, in state court. The federal government immediately announced its intent to appeal the decision to the U.S. Supreme Court. Meanwhile, however, to prevent Hale and Ramsey from fleeing any prosecution, they arranged for the men's arrest on state murder charges. Getting a jury to convict in Osage County would be next to impossible, but they had no other option.

Hale and Ramsey

The preliminary hearing on March 12 in Pawhuska was a spectacle. "Seldom if ever has such a crowd been gathered in a courtroom before," reported the Tulsa Tribune. The crowd included "well-groomed businessmen" and "society women", as well as "cowboys in broad-brimmed hats" and "Osage chiefs in beaded garb." Mollie Burkhart was there. So was Hale's wife. Things went fairly predictably until the afternoon session when Ernest Burkhart took the stand. One of Hale's lawyers rose and asked permission to meet privately with Burkhart on the ground that he had not been advised of his rights. "This man is my client," he insisted. Asked by the judge if the attorney's assertion were true, Burkhart said, "He's not my attorney--but I'm willing to talk to him." To the dismay of prosecutors, Burkhart stepped down from the witness stand and trotted to the judge's chambers to meet with Hale's lawyers. Twenty minutes later, Hale's attorney Sargent Freeling emerged from the room to ask the court to give Burkhart the rest of the day to meet with the defense. The judge agreed.

When Burkhart showed up the next morning in court he took the stand again--but as a witness for the defense, not the state. Burkhart, contradicting his January statement, testified that he never discussed the murder of Roan with Hale. Hale looked on, grinning, as Burkhart recanted line after line of his statement.

Ernest Burkhart Trial

The trial of Ernest Burkhart for his role in the bombing of the Smith house began in May. Burkhart was tried in state court in Pawhuska specifically for the murder of Bill Smith. Attorneys for Hale were anxious to secure acquittal for Ernest because they knew that if convicted he would likely testify for the prosecution in the Roan case.

The defense produced testimony to show that the confessions of Ramsey and Burkhart were coerced. None of it was true--but no matter. It was dramatic stuff. Hale testified that a federal agent cocked a pistol behind his head and, as he turned around to see it, Agent "Smith jumped across the room, grabbed me by the shoulder, and shoved a big gun in my face." He claimed that Tom White told him, "We will have you put in the hot chair." Then, he testified, agents pushed him into a chair, put a black hood over his head, and then attached a device that looked like a catcher's mask to his head. "They talked about putting the juice to me." One agent sniffed and exclaimed, "Don't you smell that human flesh burning?"

Testimony like that gets attention. The Washington Post and other national newspapers ran stories about the alleged shocking treatment of a prisoner by federal agents. When J. Edgar Hoover demanded an explanation from Tom White, White wrote back to call Hale's story a "fabrication from start to finish." In the courtroom, defense attorneys and prosecutors shouted at each other, with one prosecutor threatening to meet a defense attorney "out in the courtyard."

The Court excluded from evidence Burkhart's confession made in Guthrie in January, but not based on Hale and Ramsey's story of torture. The judge said he thought Hale and Ramsey's allegations were implausible. Nonetheless, Burkhart made his statement in the early morning hours after a long period of detention and this, the judge ruled, was enough reason to exclude it.

But the prosecutors had one key card to play in the Burkhart trial and his name was Kelsie Morrison. On May 18, in Guthrie, Morrison had confessed to his role in Anna Brown's murder. Morrison stated that he and Byran Burkhart got Anna drunk and then drove her to a place about three miles from Fairfax. He said he took Anna "about forty steps" down a ravine and "gave her a big drink and left her." Two or three hours later, he shot Anna with a gun furnished by Hale. Anna "fell back down" without a sound. Hale paid him, he stated, $1600 for the job.

Morrison also had much to say about the explosion at the Smith home. He stated Hale had approached him "any number of times" about shooting Bill Smith and his wife "at his home at night," but that he had refused. He said that killing the Smiths would make Mollie heir to the estates, "and then Ernest Burkhart would make it right with me." The triple murders could have added about $150,000 to the estate of the Ernest Burkhart family.

W. E. (Bill) Smith

According to Tom White, who attended the trial, Burkhart "seemed to be very restless and nervous" throughout. On June 8, after his trial had been interrupted by the sudden death of his and Mollies' four-year-old daughter, Ernest Burkhart passed a note to a deputy sheriff who was escorting him from the courtroom back to jail. The note indicated that Burkhart wished to meet with prosecutor John Leahy. When the two men met in Burkhart's cell, Burkhart said he was "through lying" and didn't "want to go on with this trial any longer." He couldn't tell his own lawyer--Hale might have him killed. When Burkhart next appeared in court, he walked straight to the judge, said something to him, then announced to a stunned defense team and a courtroom full of spectators, "I wish to discharge the defense attorneys. Mr. [Flint] Moss will now represent me." Moss then said, "Mr. Burkhart wishes to withdraw his plea of not guilty and enter a plea of guilty." Burkhart read a statement indicating that he had delivered the message from Hale to his soup man, Asa Kirby, telling him the time had come to blow up the Smith house. "I feel in my heart that I did it because I was requested to do it by Hale, who is my uncle." Burkhart also admitted that the allegation of physical abuse by federal agents was a lie. The only duress, he said, was being questioned for long hours into the night. On June 21, 1926, Burkhart was sentenced to life in prison.

Hale-Ramsey Trial

By May, the U.S. Supreme Court had ruled that the Hale-Ramsey trial for the murder of Henry Roan could take place in federal court after all. On July 26,1926, in the brick courthouse in Guthrie, the trial opened with prosecution witnesses under heavy guard. The prosecution knew it faced a challenge in finding twelve untainted jurors, and they asked each potential juror during voir dire whether they had been approached by anyone interested in obtaining a particular verdict. Each swore that they had not. But the prosecutors had another concern. The victim was a Native American and many white Oklahomans, in the view of one Osage, considered the murder of an Indian as a crime on par with "cruelty to animals."

Hale (center) leaving court

Ernest Burkhart was the prosecution's star witness. After his guilty plea, with tears in his eyes, he had told White he would from then on tell the truth in any courtroom, regardless of the consequences. Burkhart told jurors that Hale's original plan to kill Roan was to use poisoned moonshine, a method he had employed before with success. (In the years of the "reign of terror," more Osage were poisoned that killed by all other methods.) He testified that Hale became upset when he found out that Ramsey had shot Roan through the back of the head and taken the gun. Ramsey was supposed to have shot Roan through the front of the head, then left the gun by his side to make the death appear to be a suicide. If he'd only followed instructions, Hale had said, "nobody would have known."

Bootlegger Matt Williams testified that Hale revealed to him in January 1923 that he had taken out a $25,000 life insurance policy on Henry Roan with the Denver Insurance company. Hale set that he had lent Roan some cattle and could make it look like the policy was "security for the cattle deal." He added that he had made arrangements with John Ramsey to "bump Roan off." Three days after Roan's murder, Williams testified, he met with John Ramsey who told him he shot Roan after luring him with whiskey. Interestingly, Williams said that Hale was already thinking about legal strategy. He told Williams that he had talked to his lawyers about whether "pulling off jobs" on Indian lands would allow federal prosecutions, and that his lawyer had assured him that "the government had no jurisdiction." Dick Gregg, a member of the notorious Al Spencer gang of bank robbers, testified that Hale had unsuccessfully tried to hire him to murder Osage members. O. C. Webb testified that before the Roan murder he heard Hale tell Ramsey, "We are ready to go--everything is ready to go." After Hale was arrested and concerned about what Webb knew, he said to Webb, "I want you to stand pat old boy--I'll depend on you!" Other witness testimony focused on Hale's policy on the life of Roan. An insurance examiner testified that when he asked Hale if he was planning to kill "that Indian" for his insurance, Hale answered "Oh God, I am--hell yes!"

When the defense had its turn, Hale testified, "I never devised a scheme to have Roan killed. I never desired his death." The defense also called to the stand a number of witnesses who either corroborated alibis for Hale or Ramsey, or tried to shift blame to Roy Bunch, who had been having an affair with Roan's wife, or to an outlaw (since deceased) named Curley Johnson. Much of the testimony was perjured--bought and paid for by Hale. Typical was the testimony provided by Buster Jarrett, residing in a Pawhuska jail on a bank robbery charge at the time of trial, who testified that he saw Roy Bunch pay Curley Johnson for killing Roan. (Jarrett later confessed that he was persuaded to give his perjured testimony during a 90-minute jail cell visit from Hale's attorney. Hale's attorney promised to "snatch him out of prison" if he testified as asked.)

In his closing argument, prosecutor Roy St. Lewis told jurors that the evidence proved that "the richest tribe of Indians on the globe has become the illegitimate prey of white men." And the worst predator of all has been the defendant, "the ruthless freebooter of death."

The jury deliberated for five days but could not reach a verdict. St. Lewis announced in court that he knew the reason why: at least one, and possibly more, jurors had been bribed. (Later, it was revealed that the jury stood 6 to 6 on the issue of guilt.) There would be another trial.

The retrial began on October 20 in Oklahoma City. The prosecution's witness list for the retrial was similar to the first trial, but the examination of witnesses was tighter and more focused. The defense made an effort to pin the blame for the Roan murder on Ernest Burkhart. Burkhart conceded that he had plead guilty to murdering his wife's sister, her husband, and their servant. Rattling off the list of Mollie's murdered, and probably murdered, relatives, Hale's attorney asked, "Has your wife now any surviving relatives outside of the two children she has by you?" "She has not," Burkhart answered.

After a day of deliberations, the jury announced that it had reached a verdict. When the clerk read the verdict, Hale and Ramsey appeared stunned. Guilty--guilty of murder in the first-degree. The vote on the first ballot had been unanimous. The two men were sentenced to prison for the "period of your natural lives." Hale and Ramsey were sent to Leavenworth, Kansas to serve their sentences. Just months later the two men would meet the newly appointed warden, Tom White.

Ravine where Anna Brown's body was found

Kelsie Morrison Trial

In 1927, Kelsie Morrison faced trial for the murder of Anna Brown. Morrison had recanted his confession and even, as discovered from a letter sent to Hale and seized by prison authorities, threatened to "burn" down authorities "if I ever get the chance." Morrison promised his "old friend" Hale that if called as a witness in his trial, "I won't forget you" and "I will be there with bells on."

Bryan Burkhart, who had previously been acquitted in his own state court trial for the murder of Anna Brown, had immunity and testified for the prosecution. So did Morrison's former wife, Katherine Cole. Cole testified that she saw Morrison and Bryan Burkhart walk a very drunk Anna Brown from their car to a ravine. "I realized they were going to do something to Anna Brown, and it scared me very much. I was afraid to say anything to Kelsie for fear that he would do something to me." They returned, she testified, about a half hour later without Anna. Later that night, when she asked Kelsie about what happened, Kelsie "cursed me and told me to keep my mouth shut." Katherine Cole was right to worry. Another witness, Dewey Selph, testified that Kelsie asked him to "get shut of Katherine" (kill Katherine) "because she knew too much about the Anna Brown murder deal." Later, Selph met with Hale to discuss plans to murder Cole--plans which were never executed. Matt Williams, a bootlegger, testified that he saw Burkhart on the night Brown was killed. Burkhart told him "he had to take care of some business for Uncle Bill that night" and that Kelsie Morrison was going to meet them at the Arkansas River Bridge." Three or four days later, Williams said he met Morrison, who told him that Hale had "him do the worst job he ever pulled" and that now Hale was refusing to pay him what he'd promised for killing Anna. In Morrison's telling of the murder, Williams said, he knocked Anna from behind "while Bryan Burkhart was loving Anna" and then carried her from the car, where he shot her in the head. The jury found Morrison guilty.

Hale-Ramsey Final Re-Trials

Yet the trials were still not over. Hale and Ramsey appealed their convictions. The Eighth Circuit concluded that the trial court's refusal to Hale's request to be tried separately was prejudicial in light of his co-defendant's confession. In addition, the court noted that Hale and Ramsey were tried in federal court for the western district of Oklahoma, when they should have been tried in federal court for the northern district of Oklahoma, where the crime allegedly occurred. Hale and Ramsey were re-tried separately. Hale was convicted in January 1929 and Ramsey was convicted ten months later.

John Ramsey (mugshot)

Aftermath

The trials were over. The murders, for the most part, stopped. But that did not mean every murderer had been brought to justice. David Grann, author of the bestselling book about the Osage Reign of Terror, Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI, notes that the series of murders in the 1920s still ravages generations of Osage. He quotes a great-grandson of Henry Roan who says the murders are still "in the back of our minds....You just have it in the back of your head that you don't trust anybody."

Grann devotes a chapter of his book to describing his efforts to identify some of the killers who escaped justice. One likely killer identified by Grann was a bank president, and intimate associate of Hale, named Herbert G. Burt. Burt made a fortune lending money to the Osage "at astronomical interest rates." Grann makes a convincing case that Burt had a strong financial motive and was behind both the poisoning of George Bigheart and the murder of attorney W. W. Vaughan, who was thrown off a moving train after meeting with Bigheart as part of his investigation into the Reign of Terror murders.

Grann also re-examined evidence relating to the Charles Whitehorm murder. He concluded that the evidence suggested three people, including Whitehorn's half-white, half-Cheyenne wife, Hattie Whitehorn, and two other co-conspirators were responsible for the murder. The FBI initially looked at the evidence in the Whitehorn case but dropped it, Grann writes, because it "did not fit into the bureau's dramatic theory of the murders: that a lone mastermind (Hale) was responsible for all the killings." Grann draws an important lesson from the Whitehorn case: "the evil of Hale was not an anomaly." Far from the bureau's official estimate of twenty-four murders, Grann notes that scholars and investigators "now believe that the Osage death toll was in the scores, if not the hundreds." Most of the victims might well have died through hard-to-detect poisons, including the injection of massive amounts of morphine into already drunk Osage members. The resulting deaths, in almost all such cases, would be reported simply as deaths from alcoholic poisoning.

The list of murderers, and the "web of silent conspirators" who help them, included many of the most powerful whites in Osage County. The list includes bankers, doctors, traders, undertakers, lawyers, wealthy ranchers, and even lawmen. Grann quotes Osage leader Bacon Rind, who remarked in 1926, "There are men amongst the whites, honest men, but they are mighty scarce."

And what about the main players in the bureau's drama? Mollie divorced Ernest Burkhart during the series of federal trials. She remarried in 1928. In 1931, a court declared a previous order declaring Mollie to be incompetent was vacated and she became free to spend her money as she so wished. Mollie died in 1937 at the age of 50.

John Ramsey was paroled in 1947. Ernest Burkhart paroled in 1937, but then robbed a bank before being released again in 1959. He spent his last years in a trailer home with his brother Bryan.

William Hale served 21 years in Leavenworth before being paroled in 1947. He spent many of his prison years working on a pig farm. While working as the warden of Leavenworth, Tom White always insisted that Hale be treated just like any other prisoner. Hale never admitted ordering any killings. Before leaving jail, Hale wrote a letter in which he expressed the desire to return to Osage County. "I had rather live at Gray Horse than any place on earth." But it was not to be. As a condition of his parole, he was required to stay outside of the state of Oklahoma. Hale died in a nursing home in Arizona in 1962 and was buried in Wichita, Kansas.

The Osage Nation now includes over 10,000 members, though less than have live in Osage County. The boomtowns of the 1920s are all but gone. The gushing oil wells of an earlier day have mostly given way to "stripper" wells which generally produce less than 15 gallons a day. About 75% of the headrights to oil on the Osage reservation remain in member hands. Today, the Osage seem ready to move on from oil to a greener form of energy. In 2015, a new windmill farm sprang to life in Osage County. The times are a-changin'.

Casinos now bring in more money than oil. The Osage wealth allowed the Tribe to purchase media mogul Ted Turner's 43,000 acre Bluestem ranch in 2016. In Pawhuska, Oklahoma, visitors to the Osage Nation Museum, the oldest tribally owned museum in the United States, can explore exhibits on Osage art, culture, and history--including the Reign of Terror.