One beautiful girl, two extravagant and prominent men. Throw in jealousy and a family history of mental instability and you have the recipe for a shocking murder, at an outdoor theater in the heart of New York City in front of nearly a thousand witnesses. The trial that followed was quickly dubbed "the trial of the century." The 1907 trial, and a second the next year after the first jury hung, helped closed the curtains on America's "Gilded Age."

Fifteen-year-old Evelyn Nesbit came to New York City in December 1900 to continue a modeling career that had begun to blossom in her home state of Pennsylvania. Within days of her arrival, one of the city's most respected painters, James Carroll Beckwith , hired what he called this "perfectly formed nymph" to pose twice a week at his 57th Street studio. Soon, Nesbit, with her fresh and inscrutable face, found herself in great demand for modeling jobs, both among photographers and portrait artists. The girl dubbed by reporters as "the Little Sphinx" appeared on post cards and magazines such as Cosmopolitan, Vanity Fair, Harper's Bazaar, and the Ladies' Home Journal. Evelyn Nesbit became America's first genuine pin-up girl. Her stunning looks overcame a lack of training as a actress when, in May 1901, she accepted a role as a chorus girl in Broadway's most popular musical of the day, Florodora.

The Red Velvet Swing

Nesbit's charms attracted the interest of Stanford White , New York City's most famous architect. White-designed landmarks could be found all over the city, from his Washington Memorial Arch to the Bowery Savings Bank to the Gould Library at NYU. White's Madison Square Garden, a large entertainment center in Spanish Renaissance mode, was the site for concerts, horse shows, balls, exhibitions and live theater. The building featured a soaring, elegant tower (then the city's highest) topped by a scandalously nude thirteen-foot statue of Diana shooting a bow and arrow. (Diana's nakedness became an obsession of the prudish Anthony Comstock, who temporarily succeeded in getting the naked goddess bundled in clothing, only to watch it blow off in a nasty gale. White responded by putting lights below Diana which drew even more attention to the statue.)

White biographer Brendan Gill described the architect as a "big, bluff, open, lovable man of superb talent, and the predatory...satyr." Stanford White had a nearly insatiable desire for young girls and wild sex. In 1887, White and a group of fellow New York City libertines started the Sewer Club, a place for drinking and sexual excess. Girls seemed to find White's money and power irresistible, enabling him to keep several affairs going at a time. White's granddaughter, Suzannah Lessard, in her biography Architect of Desire, describes her talented forebear as "all over the place sexually--he was out of control."

Forty-six-year-old Stanford White persuaded another Florodora chorus girl to arrange Evelyn Nesbit's attendance at what Nesbit came to assume was a "society luncheon" at a posh New York City venue. Instead, Nesbit's introduction to White came at lunch for just four at the architect's West Twenty-fourth Street apartment. Later, Nesbit recalled thinking White "terribly old," but she instantly found attractive White's boundless playfulness. After lunch, White led Evelyn and her female friend to an upstairs room where a red velvet swing hung suspended from the ceiling. White urged Nesbit on to the swing, gave several vigorous pushes, and then laughed and clapped with delight as the young object of his fancy soared toward the ceiling.

Over the course of the next several weeks, Stanford White won the confidence of Evelyn's protective, yet gullible, mother. With Mrs. Nesbit convinced that the clever and kindly White had only a paternal interest in her daughter's welfare, she gave her blessing to Evelyn's attendance at a series of lunches and parties hosted by the architect. Mrs. Nesbit's decision to encourage the relationship doubtless was made easier by White's generosity; she began calling Stanny their "benefactor." Evelyn, her mother, and White became, in the words of the young model, "fast friends."

About two months after the relationship began, Mrs. Nesbit took a trip back home to Pittsburgh after White promised to pay the fare and make all necessary arrangements. Before she left, Mrs. Nesbit made Evelyn promise to see no one other than Mr. White while she was gone. A few days later the inevitable happened. A cab requested by White deposited Evelyn, who was expecting to be entertained at another party, at his apartment. There were no guests to be found. White apologized, explaining that all his other invitations were turned down, but they'd make the best of the evening. The champagne flowed freely and before long, Nesbit, according to her account, passed out. When she awoke, she found herself lying nude on silk sheets in a mirrored canopied bed. A streak of blood ran down her inner thigh. As Evelyn started to cry, White passed her a kimono and said, "Don't cry, Kittens. It's all over. Now you belong to me."

It took Evelyn several days to sort out her complicated feelings, but eventually she returned to the man she later called her "benevolent vampire." For the next six months, White and Nesbit saw each other almost daily. For her seventeenth birthday in December 1901, White presented Evelyn with a pearl necklace, three diamond rings, and a set of white fox furs. Nesbit soared again on the red velvet swing, but not always with her clothes. Decades later in her memoirs, Nesbit would say of the middle-aged man she gave her virginity to: "Stanford White was a great man...That he did me wrong, that from certain moral standards he was perverse and decadent, does not blind my judgment."

In the late summer of 1902, a new and younger man entered Evelyn's life. John Barrymore, a rakish twenty-one-year-old newspaper sketch artist (Barrymore would later become one of the greatest stage actors of his generation), met Evelyn at one of White's festive parties in the Tower of his Madison Square Garden. When Stanford White set off for Canada on a two-week fishing trip, Barrymore made his move and soon the young couple's budding relationship became a focus of town gossip. When Mrs. Nesbit learned of her daughter's new love, she swept into action, asking Stanford White to intervene and break up the relationship. Faced with a two-prong attack from White and her mother, Evelyn reluctantly agreed to a hastily thrown-together plan to enroll her in a boarding school in New Jersey. Meanwhile, yet another man had been watching her every move.

Harry K. Thaw

To Evelyn, during the run of the show "Wild Rose" in which she starred, "Mr. Munroe" was just one of the countless men who seemed to have a crush on her. "Mr. Munroe"attended forty performances of "Wild Rose" and regularly sent Evelyn flowers, letters, and offers of larger gifts. He also asked for dates, which Evelyn politely declined. "Mr. Munroe" was, in fact, eccentric millionaire Harry K. Thaw from Pittsburgh. Thaw's interest in Nesbit seemed to have its source in Thaw's obsessive hatred of Stanford White, who he believed was blackballing him from New York City clubs he sought to join, and who he considered to be a "wholesale ravisher of young girls." Fueling Thaw's love of Nesbit was his desire to protect Evelyn from the dastardly Mr. White. In 1902, "Mr. Munroe" finally succeeded, through an intermediary, in arranging a lunch date with Evelyn. Meeting her for the first time in a restaurant at high tea, "Mr. Munroe" fell to his knees, kissed the hem of Nesbit's dress, and pronounced Evelyn to be "the prettiest girl in New York." Thaw was nothing if not persistent in his courtship of his dream girl, and in due time revealed himself, with great flourish, to be the very rich "Harry Kendall Thaw, of Pittsburgh!" Evelyn later wrote, "A disguised Napoleon revealing himself to a near-sighted veteran on Elba could not have made the revelation with greater aplomb."

In April of 1903, while nearing the end of her term at boarding school, Nesbit developed acute appendicitis requiring live-saving surgery. Thaw rushed to her hospital room and kissed Evelyn's shaking hand. During the operation, Thaw and Mrs. Nesbit discussed Evelyn's future. A few months later, in what Evelyn later would call "the worst mistake of her life," she and her mother and Harry Thaw sailed from New York for an extended vacation in Europe.

In a Paris hotel suite, at Thaw's urging, Evelyn Nesbit told the story of her champagne-fueled deflowering two years earlier in Stanford White's mirrored bedroom. As she did so, Harry shuddered, gaped, whimpered, and went limp. Over and over again he said, "Poor child! Poor child!" or "Oh, God! Oh, God!" The story of that fall night on 24th Street would continue for years to haunt the mind of Harry K. Thaw.

Weeks later, after her mother had sailed back to the United States, Evelyn found herself with Harry in a rented castle in rural Austria. In her biography of Nesbit, American Eve, Paulu Uruburu describes the castle as "a huge Gothic nightmare of cold stones and dimly lit, drafty passageways, grimmer than anything in the Grimm brothers' tales." On her first night at the castle, asleep in her bedroom, Evelyn was suddenly awakened by a "bug-eyed, seething, and startlingly naked Harry," who threw her coverings aside and began lashing her legs with a leather riding crop. Harry, then tore the nightgown off of the bleeding Evelyn and proceeded to rape her, screaming all the time about Stanford White and his debauchery.

One would not think, after that nightmarish assault in a castle, that a marriage between Harry and Evelyn would be possible. Yet it happened. Two years of non-stop pursuit, aided by a more solicitous tone, lavish spending, and considerable attention to her mother, landed Thaw his prize. On April 5, 1905, in a private ceremony in Pittsburgh, Evelyn Nesbit became Mrs. Harry K. Thaw. The couple moved into the large, depressing Pittsburgh mansion that was also home to Harry's mother. For the next fourteen months, Evelyn spent much of her time feeling like a bird in a gilded cage.

June 25, 1906: Murder at Stanny's Garden

In the spring of 1906, Evelyn and Harry decided to take a trip to England. Harry scheduled a June 28 sailing on a German luxury liner from the port of New York. Plans were made to spend a week in the city before heading off across the Atlantic.

Around six o'clock on June 25, Evelyn left her suite in the Lorraine hotel on Fifth Avenue. Evelyn met Harry at a nearby bar, where he already had put three drinks already under his belt (and paid the $3 bar tab with a hundred dollar bill), and then the couple headed off for Cafe Martin. In the course of a dinner at Cafe Martin shared with two friends, Evelyn was startled to see Stanford White, accompanied by his son, walk into the restaurant. In spite of the near-record heat of the day, Evelyn, as she recalled later, "went cold with fear" for her husband's reaction if he were to spot the architect. Sensing a change in his wife's mood, Harry asked Evelyn if anything was wrong. She scribbled a note: "The B was here but has left." After reading the note, Harry kept his emotions surprisingly well in check, it seemed to Evelyn, until after dinner when he retrieved his straw hat from a cloakroom attendant. Harry slammed the hat on to his head with such force as to crack the brim. As they left the restaurant, Harry announced he had bought tickets for a new musical, Mamzelle Champagne, playing at Madison Square Garden's open-air rooftop theater .

Sometime during the show, Harry learned that Stanford White planned to catch part of the show. Later, witnesses reported seeing Thaw pacing around the rear of the theater "like a caged tiger." Shortly before eleven o'clock, with the show approaching its conclusion, White took his customary seat at a small table five rows from the stage. It took Harry a few minutes to become aware of his arch-enemy's entrance, but once he did, he stood up with a dazed look in his eyes. Evelyn suggested that they leave, and they began heading towards the elevator. As Evelyn conversed briefly with a friend, Harry slipped away.

As a line of chorus girls sang "I Could Love a Thousand Girls," the audience heard a burst of gunfire, followed quickly by two more shots. Evelyn knew immediately what had happened. "He shot him!" she cried. As the architect's blood poured on to the tablecloth of his overturned table, Harry Thaw shouted his triumph: "I did it because he ruined my wife! He had it coming to him! He took advantage of the girl and then deserted her!" White had been shot twice in the head and once in the shoulder. The first shot was fired from a distance of about twelve feet, after Thaw had made a beeline to White's table and then pulled a revolver out from under his coat. The second and third shots came from even closer range, perhaps two or three feet away.

Chaos ensued. Some members of the audience screamed, while others rushed for the exit. Meanwhile, L. Lawrence, manager of the show jumped on a table and commanded that the show go on. "Go on playing!" he yelled. "Bring on that chorus!" As Thaw was led away by a police officer, Evelyn said to her husband, "Look at the fix you are in." "It's all right dear," Harry replied, "I have probably saved your life."

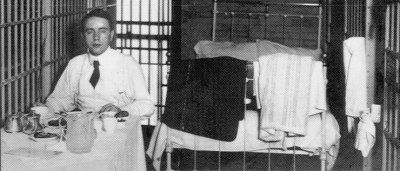

At three a.m. the next morning, Thaw was charged with murder and escorted from the station house across the Bridge of Sighs into the Tombs prison , where he was locked in a humid cell. Evelyn managed to escape the press (she earned the name "the Girl Houdini") and spent two sleepless nights holed up at the apartment of a friend in the theater district. Meanwhile, the city was abuzz with rumors about possible motives for the killing, and Thomas Edison's studio worked overtime to rush a film version of the Rooftop Murder into nickelodeons.

The First Trial: "Dementia Americana"

The original strategy of District Attorney William T. Jerome was to have Thaw declared legally insane and shipped off to an asylum. The state would save a great deal of money, and the theory seemed consistent with a defendant who shot his victim in front of one thousand witnesses and then used every opportunity to boast about his good deed. Thaw's original attorney, Lewis Delafield, seemed content to go along with the district attorney's approach, concluding it to be the only sure way his client could avoid the electric chair. Harry Thaw, however, wanted no part of an insanity plea, and quickly labeled his attorney "The Traitor" for even suggesting it. Three weeks after Delafield took the case, Thaw dismissed him. Harry looked forward to his trial and his chance to expose the "set of perverts" who preyed on young girls and deserved nothing less than death.

Jury selection began in January 1907. After questioning six hundred prospective jurors, a jury of twelve men was finally seated. Meanwhile, the proud Thaw family, unable to stomach a traditional insanity case, settled on proving, through their new team of lawyers, that Harry had experienced a "brainstorm," a brief bout of temporary insanity that could be expected of almost any American male put to the same stresses.

To prosecutor Jerome, the case was a simple one: Thaw killed White out of simple jealousy. Thaw was not Evelyn's savior, and Jerome intended to disprove any such suggestion. He told reporters that if Evelyn sought to portray her husband as a hero, he would "tear her limb to limb and exhibit the interesting remains triumphantly."

When the trial opened on February 4 of Justice James Fitzgerald , the prosecution delivered a seven-minute opening statement, offered two hours of testimony outlining the bare events surrounding the rooftop murder, and then rested its case. Eyewitness Warner Paxon described the shooting and told jurors how he led Thaw out of the theater and down an elevator, to where a police officer might be found. Paxon testified that Thaw explained as he was being led away, "I did it because he ruined my wife," to which his wife responded, "Yes, Harry, but look at the fix you're in now." Thaw replied to Evelyn, "I probably saved your life." Coroner Timothy Kahane testified that White died instantly, from "a cerebral hemorrhage as the result of pistol shot wounds in the skull."

After a recess, defense attorney John B. Gleason gave his opening statement. As Harry Thaw sat with his eyes fixed on the table in front of him, Gleason that the defense will primarily rest on evidence that "the defendant killed White under the delusion that he was the agent of Providence." Gleason said that Thaw had "for three years been suffering from a disease of the brain which culminated in the killing." Gleason blamed the insanity on "two things, heredity and stress." He promised jurors that they would learn from Evelyn Nesbit's "own lips" about a conversation she had with Thaw in June 1903 that would account for Thaw's obsession with White.

The first witness for the defense was Dr. C. C. Wiley, the Thaw family psychiatrist. Dr. Wiley testified that the murder "was the act of an insane man" and that Thaw's comment to his wife, immediately after the shooting, "I have probably saved your life" was "an indication of insane delusion."

Next on the stand was Benjamin Bowman, a doorkeeper at Madison Square Garden, who testified that, in December 1903, Stanford White in the belief that Evelyn had left the theater with Harry Thaw, "pulled a pistol from his pocket and muttered, 'I'll find and kill that [vulgar term omitted in record] before daylight." Bowman said that he warned Thaw of White's threat and that Thaw became "black in the face with anger."

When the clearly over matched John Gleason withdrew as defense attorney, Delphin Delmas of San Francisco (famous for never having lost a case) was appointed the new lead counsel. With the appointment, the defense strategy changed to one much more to Harry Thaw's liking. Instead of focusing on Harry's alleged madness, Delmas worked to make the jury hate Harry's victim so much that they could forgive his client's murder. No one, Delmas knew, was in a better position to make the jury despise Stanford White than Evelyn Nesbit Thaw. At first Evelyn was nauseous at the thought of revealing her deepest, darkest secrets in public, but she finally consented to Delmas's urgent pleading.

The public eagerly anticipated the testimony of Evelyn, who took the stand on February 8. In two hours of often tearful testimony, she told a crowded and hushed courtroom her version of the events of the night of the murder. In response to questioning from Delphin Delmas, Evelyn said she was "not a bit" interested in the play and suggested to Harry that they leave early. After Harry disappeared while she talked with another theatergoer on the way to the exit, she heard gunfire and said, "I think he has shot him."

Evelyn's description of a conversation with Harry on a June night in 1903 provided the day's most compelling testimony. Evelyn said that on that night, after Harry proposed marriage, she balked and began to cry. Harry suspected that White might be the cause of her tears and begged that she tell him the whole story of her first sexual encounter with the architect. Telling the story to jurors proved too much for Evelyn. She fell back in the witness chair, collapsed, and murmured: "I can't go on! I can't! I can't" After the courtroom windows were opened and restoratives of some sort applied to Nesbit by a doctor, she continued her testimony. Reaching the climax of her story, Evelyn fought back tears as she told what happened after an evening of drinking champagne in White's apartment:

"When I came to myself I was greatly frightened and started to scream. Mr. White came and tried to quiet me. As I sat up, I saw mirrors all over. I began to scream again, and Mr. White asked me to keep quiet, saying that it was all over. When he threw the kimono over me he left the room. I screamed harder than ever. I don't remember much of anything after that. He took me home and I sat up all night crying."

Delmas asked Evelyn what White told her after that night. Evelyn replied, "He made me swear that I would never tell my mother about it....He said that it was all right--that there was 'nothing so nice as young girls and nothing so loathsome as fat ones. You must never get fat.'" According to a contemporary trial account, "the jury gasped at every sentence, shuddered at every disclosure" of the beautiful witness in the navy blue suit, white linen collar, and black velvet hat with artificial violets.

The next day, Evelyn testified about the intensifying feud between White and Thaw. She told jurors that after her return from her European trip with Thaw, White warned her to stay away from that morphine addict and arranged for her to meet an attorney, Abe Hummel, who could protect her from Thaw. She testified that Hummel "put in [an affidavit] a lot of stuff that I had been carried away [to Europe] against my will"--even though she told him "I certainly had gone of my own accord." Evelyn testified that when she later told Harry about her encounter with White's lawyer he became "very much agitated" and called Hummel "a blackmailer." After her conversation with Harry, Evelyn went down to Hummel's office and demanded that the papers she signed be destroyed. "Then they put the paper in a big jardiniere," she testified, "and burned it." Evelyn said that anytime thereafter that she reported to Harry about even the briefest chance meeting with White, Harry "bit his nails and look excited."

Delmas quizzed Evelyn about some of the more scandalous episodes in White's past, including his infamous "girl-in-a-pie" stag dinner. Evelyn testified that a girl, about age 15, in a gauze dress "was put in a big pie with a lot of birds." During the dinner, "the girl jumped out of the pie and the birds flew all about the room." Evelyn said, "I told Mr. White I had heard [later] he had ruined the girl that night, but he only laughed."

In his cross-examination of Nesbit, Jerome tried to sully Evelyn's reputation. Through a series of questions, Jerome suggested that she posed in the nude, but Nesbit ("her cheeks flamed with color") repeatedly denied ever appearing before a painter or photographer in the all-together. She also denied engaging in "unruly" behavior in 1901, such as setting off alone with a man on a yacht. Jerome asked her whether, prior to her heart-to-heart with Harry in Paris, that she recognized that sexual activity with an older, married man was wrong. Evelyn said she knew it was "indelicate and vulgar," but that she didn't fully appreciate its wrongfulness "until I went to Paris." She admitted to later developing a "hostility against [White]" for certain things he had done, but refused to call it "enmity." Nesbit admitted that for many months White provided financial support for her and her mother. She surprised most in the courtroom by saying of White, that except for having "a strong personality," he "had been a very grand man. He was very good to me, and very kind. When I told Mr. Thaw this, he said it only made White all the more dangerous." Testifying that day was not easy for Evelyn; according to an account of the trial, "her tears flowed almost constantly."

The defense produced an affidavit from the New York City's leading self-appointed defender of decency, the Reverend Anthony Comstock. Comstock stated that he last saw Thaw about three weeks before he shot White, Harry was "in a desperate state--like a man who is well-nigh frantic. He said to me wildly: 'You must keep on, you must stop this man, he must be stopped now--at once.'" The defense also introduced a letter sent by Thaw to Comstock which described, in words and drawings, White's West Twenty-fourth Street studio, a place "consecrated to debauchery" in which "workmen outside the building have frequently heard the screams of young women." Thaw's letter included sketches of the red velvet swing and the mirrored bedroom.

Psychiatrist Dr. Charles Wagner bolstered the defense's temporary insanity theory. Wagner said Thaw acted out of "a sudden impulse" and "had no idea of killing White up to the very time he shot him." Wagner said Thaw told him, "I knew he was a foul creature, destroying all mothers and daughters in America, but I wanted to bring him to trial." Thaw told him he fired the shot because "Providence took care of it." Wagner said Thaw only carried a gun that night out of fear of "thugs" that "were the hired agents of Stanford White."

Mrs. William Thaw, Harry's mother, was the defense's last witness. She testified that White had sent her son spinning into a downward emotional spiral. Harry, she said, repeatedly blamed White, who he called "the worst man in New York," for "ruining his life." She told jurors that White caused her son to spend countless sleepless nights sobbing in bed. As Mrs. Thaw left the stand, Delmas announced, "the defense rests."

Then, in a startling change in course apparently caused by Jerome's conclusion that the jury was buying the defense's temporary insanity theory and a death verdict was now unlikely, the prosecution suddenly changed course and sought to prove Thaw insane, both at the time of the murder and at present. Jerome introduced what the press called "the most remarkable exhibit ever introduced in a New York law court," Nesbit's October 1903 affidavit drafted in Abe Hummel's law office and produced for the case of Evelyn Nesbit v Harry K. Thaw. The affidavit described Evelyn's terrifying night in an Austrian castle during which she was approached by Thaw with "his eyes glaring and his hands grasping a raw-hide whip." Nesbit, in the affidavit, asserted Thaw "tried to choke me" and "and inflicted on me several severe blows with the rawhide whip." As Evelyn "screamed for help," Harry "renewed his brutal attacks until I was unable to move." The affidavit asserted that never thereafter did Thaw "attempt to make the slightest excuse for his conduct." Evelyn, in her statement, also alleged Harry "was addicted to the taking of cocaine." Jerome called to the stand a parade of alienists, as psychiatrists were generally called at the time, who expressed their opinion that Thaw remained dangerously insane.

The district attorney's sudden shift in strategy led to an angry shouting match between attorneys. Jerome said the law let him have it both ways: "[Thaw] is a paranoiac, and while he is insane, he is not insane in the eyes of the law, for strictly speaking he knows the nature and quality of his acts." The district attorney conceded that he had considered requesting the court to appoint "a lunacy commission" to evaluate and submit a report on Thaw's condition, and Delmas announced his opposition to the idea. Jerome quoted from an affidavit of alienist Dr. Carlos MacDonald, which stated that Thaw suffered from paranoia from "which it is reasonably certain he will not recover, and that the discharge of the said Harry K. Thaw would be dangerous to the public peace and safety." A few days after arguments, on March 26, Justice Fitzgerald announced that he had appointed a commission of disinterested psychiatric experts to prepare a report on Thaw's sanity or insanity.

The first days of the commission's hearings included an extensive mental and physical examination of Thaw. The commission's questions, and Thaw's answers, were never made public. After his appearance, Evelyn told reporters, Harry "is cheerful and feels confident the commission will decide in his favor." On April 4, the commission announced its finding: "no indication of insanity at the present could be found in the speech, conduct, or physical condition of the defendant." The commission concluded that "Harry K. Thaw was and is sane and was not and is not in a state of idiocy, imbecility, lunacy, or insanity." Thaw and the defense expressed pleasure with the conclusion. "It is only what I expected," declared Harry, "I am as sane as any man on earth."

On April 8, Delphin Delmas delivered a memorable summation for the defense. He said that the story of Harry and Evelyn was "the saddest, most mournful and tragic which the tongue of man has ever uttered or the ear of man ever heard in a court of justice." It might, he said, have been "written by the hand of Shakespeare." He reminded jurors of what happened to Evelyn after she was "lured" into the "den" of the evil "genius...who had promised to be her protector." White, he said, "perpetrated the most horrible crime that can deface a human heart." Delmas wondered whether the "hardened heart" of White could imagine that God would not hear the cry from Evelyn that went out that night into "the darkness of the great city," or that God would not forget his promise that "any one who afflicted a fatherless child would surely die." Harry Thaw, Delmas suggested to the jury, was an avenging agent of God. After he fired the fatal shots, he stood "facing the audience with his arms spread out in the form of a cross....Mr. Thaw stood as a priest might have stood after some ceremony of sacrificial offering, saying, 'All is over,' and dismissing the congregation."

Delmas appealed to the unwritten law. If Thaw is insane, Delmas said, then "call it Dementia Americana. That is the species of insanity which makes every American man believe his home to be sacred; that is the species of insanity which makes him believe the honor of his daughter is sacred; that is the species of insanity which makes him believe the honor of his wife is sacred; that is the species of insanity which makes him believe that whosoever invades his home, that whosoever stains the virtue of this threshold, has violated the highest of human laws and must appeal to the mercy of God, if mercy there be for him anywhere in the universe.”

Closing for the state, William Jerome asked the jury whether it was also part of the unwritten, higher law that a man may "flaunt a woman through the capitals of Europe for two years as his mistress--and then kill." This is not a case of Dementia Americana, Jerome said, but "a common, vulgar, everyday, tenderloin homicide." Why, Jerome wondered, would "the angel child" go back "again and again and again" to "the great ogre" who had supposedly wrecked her life? The answer, the district attorney asserted, came from Evelyn's own lips: "I know of know one who is nicer or kinder than Stanford White." Jerome argued, "You may paint Stanford White in as black color as you wish, but there are no colors in the artists' box black enough to paint" Harry Thaw.

Jerome turned to the Bible for his conclusion. "Will you gentlemen acquit a cold-blooded, cowardly, deliberate murderer on the ground of 'Dementia Americana'? If the only thing that lies between every man and his enemy is a brainstorm, then let every man pack a gun. There are two things I want to say. They are 'Vengeance is mine, saith the Lord,' and that other law that was thundered from Mount Sinai: 'Thou shalt not kill!'"

Jury deliberations began at 5:15 p.m. on April 10, 1907. After more than forty-seven hours of debate, the jury returned to the courtroom to announce that it was hopelessly deadlocked. Justice Fitzgerald declared a mistrial and dismissed the jury. The final vote, it was later revealed, had been seven for conviction of murder in the first degree and five for acquittal.

The Second Trial and Epilogue

The second trial was shorter, less sensational, attracted less attention, and was more predictable in its outcome than the first. Thaw's new defense team calculated that an acquittal under a self-defense or "Dementia Americana" theory was not possible, and that the only by pleading insanity could a prison term be avoided. Let's get Harry sent off to the insane asylum, the defense reasoned, then worry later about proving him sane enough to be let out.

The second trial opened on January 6, 1908 in the courtroom of Justice Victor J. Dowling. Pushing aside family scruples that affected the first trial, Thaw's new attorney Martin W. Littleton proceeded to lay bare the emotionally troubled history of the Thaws. Instead of attacking Stanford White, Littleton concentrated on proving his client "absolutely insane." Mrs. William Thaw testified not only about her son's strange behavior, but also about epileptic and weak-minded uncles who ended up in asylums. Harry's household nurse, who took care of him when he was only three or four years old, testified that he was moody, nervous, and had frequent spells during which he stared, twitched his mouth, threw himself back, and howled. Harry's kindergarten teacher remembered that Harry would tear off his clothes, throw chairs against the wall, and "spend his energy on inanimate things." She testified that after three years of dealing with Harry, she told his mother that the child had "a peculiar brain." A mathematics teacher during Harry's high school years recalled that Harry would stare, smile without warmth, and "walk in a zig-zag manner." Moving into Harry's adulthood, Littleton produced as witnesses a series of physicians and alienists, including a hotel physician in Paris who treated Harry after a probable suicide attempt using poison. Other doctors testified that they had diagnosed Thaw to be suffering from mania, paranoia, and other diseases of the mind. The consensus seemed to be that Thaw now suffered from a manic-depressive insanity.

Evelyn Thaw testified again in the second trial, but this time included evidence suggesting that Harry was mentally unstable. For example, she told jurors that a few weeks after telling her tale of lost virginity, Harry attempted to poison himself by swallowing laudanum. On cross-examination, she conceded that that this fact had been left out of her testimony in the previous trial at the insistence of defense attorney Delmas, who said "it would make him out too crazy."

District attorney Jerome, again heading the prosecution, argued in his summation that Thaw understood, when he pulled the trigger at the rooftop theater, that was he was doing was wrong. As a matter of law, Jerome argued, that made Thaw sane and responsible for his actions. Jerome ridiculed much of the testimony concerning Thaw's earlier life suggesting, for example, that "his fits of temper as a child...were the ordinary spells for which other children received a good spanking." Concluding, Jerome told jurors this was not an insanity case, it "was a fight over a poor little waif."

The next day the jury announced its verdict: "We find the defendant not guilty on the ground of insanity at the time of the commission of his act." Justice Dowling dismissed the jury and took from his desk a memorandum and began reading it. Dowling declared that Thaw's discharge would be "dangerous to public safety" and ordered him sent to the Matteawan State Hospital for the criminally insane "until thence discharged by due course of law." Harry Thaw, apparently expecting to be set free after the jury's verdict, grew intensely angry upon hearing the judge's words.

Seven years later, in June 1915, a jury convened in the Supreme Court of New York to determine whether Harry Thaw was now sane enough to be released from Matteawan. Evelyn Thaw, having lost whatever feelings she had for Harry at the time of the murder trial, offered no testimony this time. (In fact, she took up temporary residence near the Canadian border so she could cross over in the event a subpoena was headed her way.) Harry calmly testified for over five hours. Asked why he waited three years to kill White, Thaw replied, "There is no answer to that question. I cannot give you one. There was no reason." The jury found Harry sane. Two days later, Harry Thaw was a free man.

Harry's marriage survived only a few more months. In 1917, Harry severely whipped a nineteen-year-old boy, was arrested and returned to the insane asylum, where he stayed until 1924. He died in 1947.

After her divorce from Harry, Evelyn married her dance partner, Jack Clifford, but that marriage would prove to be short-lived. She never remarried. In 1955, a film entitled "The Girl in the Red Velvet Swing " (starring Joan Collins as Evelyn Nesbit) rekindled interest in the Nesbit, White, Thaw story. At the time of the movie's release, Evelyn Nesbit was living quietly as a seventy-four-year old sculptor in Los Angeles. Evelyn died in 1967 of natural causes.