Tokyo World War II War Crimes Trial (1946-1948) : An Account

by Douglas O. Linder (2024)

The judges called it the “biggest trial in the world” and in many ways it was. The 1946 to 1948 trial of 25 Japanese political and military leaders for their actions during World War II covered many of the most gruesome or bloody events in the Pacific Theatre: the Bataan “Death March” of American and Filipino prisoners of war; rape and massacre in occupied Nanjing, China (as many as 20,000 rapes in the first month alone); the forced construction of the Burma to Thailand railway during which thousands of Australian and Asian prisoners died; the surprise bombing of Pearl Harbor. The aim of the Tokyo trial, like its counterpart in Nuremberg, was to establish a regime of international law that would make a safer world. The trial was big, but also unwieldy and with unexpected turns. Whether it achieved its grand ambitions is at best debatable. But the trial surely revealed, as no other event could, the complicated tensions of postwar Asia.

The War Ends. What Next?

But for Secretary of War Henry Stimson, there probably would have been no international war crimes tribunals in either Nuremberg or Tokyo. The American public (90% of it) favored swift punishment of Japanese warlords, but only 4% believed the Japanese war leaders deserved anything like a fair trial. Before his death in April 1945, President Franklin Roosevelt, as well as his influential Cabinet members, including Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau and Secretary Cordell Hull, also thought quick executions were the answer. President Harry Truman, on the other hand, was much more open to Stimson’s argument that trials, rather than summary executions, would teach needed stern lessons to the people of Axis countries about what Truman called the “crimes of the gangsters they placed in power.” Truman wrote about Nuremberg, “I believe the effect will be very great on future was—at least I hope it will prevent them.”

After Hitler’s fall in Germany, surrender by the Japanese Empire seemed only a matter of time, but in that time hundreds of thousands of lives would be lost. Truman was determined to minimize the number of lost American lives in that final count. That meant avoiding a land invasion of Japan.

On July 16, 1945, Truman learned of the successful test of an atomic bomb in New Mexico. According to Secretary Stimson, Truman was “highly delighted.” Meanwhile, Emperor Hirohito had called an imperial conference in which he pressed the nation’s military leaders to find a way to halt the fighting, which had cost the lives of 1.5 million Japanese in the last year alone.

On July 25, Truman noted in his diary that he would use the atomic bomb against Japan “between now and August 10th.” Among Truman’s top advisors, only General Eisenhower expressed “grave misgivings” about using such a terrible weapon that would cause mass civilian casualties. On July 26, Allies issued their Potsdam Declaration offering Japan one last chance to surrender or face “the inevitable and complete destruction of the Japanese armed forces and just as inevitably the devastation of the Japanese homeland.” The Declaration also stated that “stern justice will be meted out to all war criminals.”

At 8:15 a.m. on August 6, a brilliant yellow-orange flash of light appeared above Hiroshima. Truman learned of the blast aboard a cruiser in the Atlantic. He told the ship’s crew, “This is the greatest thing in history.” Japan formally protested the use of the atomic bomb, calling it an “inhuman weapon” deployed in “defiance of the essential principles of humanitarian laws.” In private, Truman said he used the bomb because he felt it “absolutely necessary” to save American lives, but that “I certainly regret the necessity of wiping out whole populations because of the pigheadedness of leaders of a nation.”

On the night of August 9, the same day that a second atomic bomb dropped on Nagasaki, Japanese leaders met in an air raid shelter at the Imperial Palace. Foreign Minister Togo Shigenori urged that Japan surrender under the terms of the Potsdam Declaration with a stipulation that it would not prejudice the status of the emperor. Maintaining the monarchy, he and most others agreed, was essential to avoiding anarchy or a leftist revolution. Army ministers urged that the nation fight on, even if millions more must die. After hours of debate, the foreign minister asked Emperor Hirohito for his decision. Wiping away tears, Hirohito said that they must “bear the unbearable”: Japan would surrender.

In the early hours of August 10, in a note passed on through the governments of Sweden and Switzerland, Japan notified Truman of its willingness to surrender. The Truman Administration accepted the surrender allowing that the form of government of Japan “be established by the freely expressed will of the Japanese people.” Japanese leaders fretted and argued over whether the language about “the freely expressed will of the Japanese people” guaranteed the continuation of the monarchy, but on August 14, the Emperor said he would broadcast the news of surrender to the Japanese people in an imperial address. That night, a group of military officers broke into the Imperial Palace hoping to find and destroy the phonograph recording of the surrender message, set to be broadcast the following day. The army, however, put down the insurrection. Two plotters committed suicide in front of the palace. On August 16, the emperor formally ordered his military to cease all hostilities immediately. The war was over. On September 2, surrender documents were formally signed in Tokyo Bay abord the USS Missouri.

Japanese delegation, as nation prepares to sign formal surrender document on the USS Missouri on Sept. 2, 1945

In a policy approved by Truman, Japan would not be divided into zones run by separate Allies; the United States would be the sole occupying authority. The United States also determined that the imperial court could be a useful tool during its occupation, and so made the decision to not blame the Emperor for the war. Preserving the Emperor might also speed the rehabilitation of Japan, something the U.S. saw in its interest as it looked to gain allies in the emerging Cold War.

Arrests and an International Tribunal Established

On September 11, the Supreme Allied Commander in the Pacific, General Douglas MacArthur, ordered the arrest of forty war criminals. The principle catch was Tojo Hideki, the prime minister of Japan during most of World War II. A group of U.S. soldiers arrived at his cottage in the suburbs of Tokyo, only to be stalled by a servant . Finally, hearing a gunshot from inside the home, they kicked in the door. They found Tojo standing upright, holding a pistol, blood streaming through his white shirt. The Americans raced Tojo to a military hospital where he wavered for hours between life and death, but eventually survived. He said it what he had hoped would be a final statement, “I would not like to be judged in front of a conqueror’s court. I wait for the righteous judgment of history.”

Others arrested that day included the entire cabinet at the time of Pearl Harbor as well as top military leaders. Included in the round up was foreign minister Togo Shigenori, even though Togo had strongly argued against war in the days leading up to Pearl Harbor. A second wave of arrests on September 21 sent additional suspects to Sugamo Prison.

A Truman Administration directive gave General MacArthur broad authority to create a special military court that might include other Allied countries, as well as establish the rules for such a court and review any verdicts the court might issue. The Administration ordered MacArthur to “take no action against the Emperor as a war criminal” without specific orders. For his part, MacArthur was happy to leave Hirohito off the hook in exchange for support by Japanese leaders for his occupation. Beginning on September 27, and on ten following occasions, MacArthur and the Emperor met privately to discuss developing events, and developed what historian Gary Bass described as “an odd, secretive rapport.” MacArthur called the Emperor’s decision to end the war “very heroic,” while Hirohito said he “personally wanted to do everything he could to avoid the war” and called the war itself “regrettable.”

Douglas MacArthur and Emperor Hirohito in 1945

The Emperor would not be indicted, despite some Allied governments (especially Australia) pushing hard for Hirohito to be tried. The Emperor had, proponents of indictment argued, appointed hawkish Tojo Hideki as prime minister and given—however reluctantly—his necessary permission (called an imperial rescript) for a declaration of war against the United States and the British Empire. Hirohito’s closest advisor, however, was not so lucky. Marquis Kido Koichi was arrested. After his arrest, Kido shocked Americans by informing them that he had kept a diary since 1930 of the inner workings of the Imperial Palace, over 6,000 entries in all. He turned the diary over to his captors. It would be immensely useful to the prosecution. Many of the major war criminals (who spent the final months of the war destroying every potentially incriminating document they could lay their hands on) resented Kido’s decision.

On October 4, MacArthur issued a civil liberties directive opening up freedom of assembly and the press in Japan. Soon thereafter, the Emperor selected a trusted liberal as the new prime minister of Japan, and just days later, General Headquarters instructed the new government to draft and implement a new liberal constitution. Japan began the process of rapidly transforming to a free country.

In the months before the major war criminals trial, a U.S. military court in the Philippines tried and convicted General Yamashita Tomoyuki, commander of Japanese forces in the islands for allowing soldiers to commit atrocities. But Yamashita’s lawyers filed a motion in the U.S. Supreme Court for leave to seek a writ of habeas corpus and challenge the jurisdiction of the Manila commission. The lawyers argued that anyone held under U.S. authority had a right to a fair trial under the Fifth Amendment, and happened in Manila to their client was not fair process. On February 6, 1946, the Court ruled 6 to 2, with Justices Murphy and Rutledge dissenting, that Congress had granted the Army to establish military courts and that no civilian courts had jurisdiction to review their decisions. Yamashita was quickly hanged and the legal way cleared for establishment of additional military tribunals to try low-ranking war criminals, and for an international tribunal of major war criminals in Tokyo.

On January 19, 1946, MacArthur issued General Orders No. 1, establishing the international war crimes tribunals. The order set off arguments among the Allied governments as to which Japanese participants in the war should be defendants. The defendants selected for trial were mostly those who attended key conferences preceding Pearl Harbor or who were determined to have played major roles based on Kido’s diary. Eventually, twenty-eight Japanese leaders were indicted. Two would never see their trial, one dying and another determined to be insane.

The indictment consisted of fifty-five counts. Defendants were accused of conspiring to wage an aggressive war; of “murdering, maiming, and ill-treating” prisoners of war”; of perpetrating “mass murder, rape, pillage, brigandage, torture, and other barbaric cruelties upon the helpless citizens of the over-run countries.” Legal authority for the charges relied primarily on international treaties, including the Geneva and Hague Conventions as well as the Kellogg-Briand Pact of 1928 making aggressive war a crime.

Truman named Joseph Keenan, a former assistant attorney general, as chief prosecutor for Japanese war criminals accused of waging a war of aggression. He was a bad choice, lacking the intellect and eloquence of Robert Jackson, the chief U.S. prosecutor in Nuremberg. Worse, Keenan knew next to nothing about Asia and was an alcoholic to boot. The State Department also proposed that MacArthur establish a bench of nine judges from various Allied countries that had signed the surrender on the USS Missouri, including judges from Britain, France, Holland, China, and Australia. Additional judges from Russia, India, and the Philippines completed the panel. Australia’s Sir William Webb, chief justice of Queensland and on friendly terms with MacArthur, was appointed chief judge of the Court.

Each defendant had a Japanese lawyer to represent him as well as American or British lawyer more familiar with a court that followed western procedures. The defense lawyers were drawn from both military and civilian ranks. Defendant generally expressed gratitude for their help and professionalism. Marquis Kido Kochi, for example, expressed amazement that the lawyers “genuinely took the side of the defendants.”

The Trial

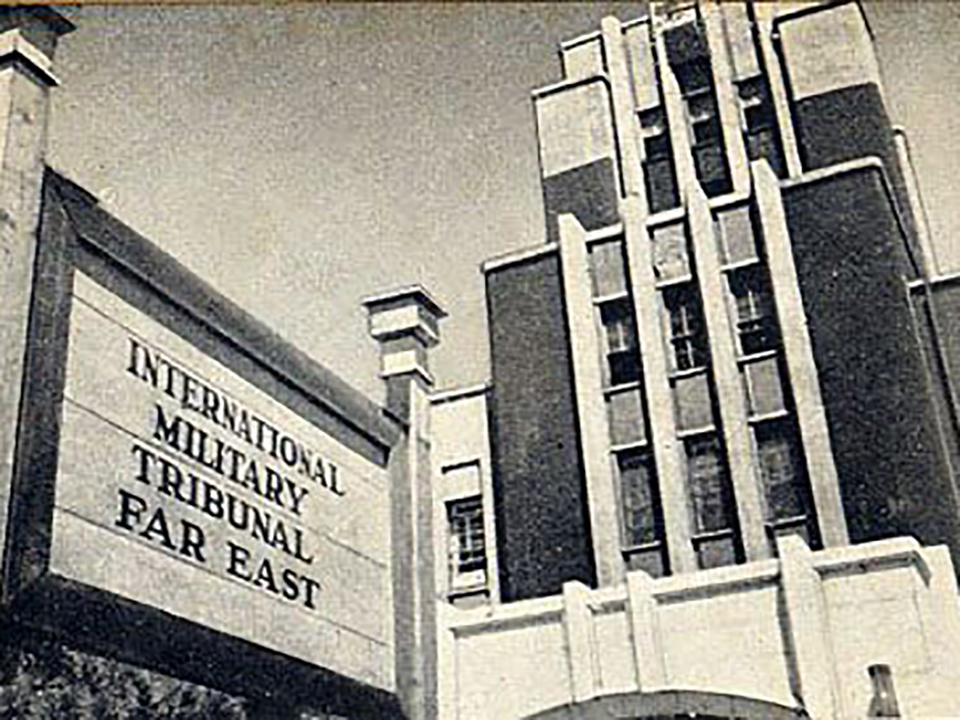

The Tokyo War Crimes proceedings opened before the International Military Tribunal for the Far East (IMTFE) on May 3, 1946 at a renovated former Army Ministry building on a hilltop in central Tokyo, two miles from the Imperial Palace. Tojo’s office during the war became a meeting room for Allied judges. The judges, in their black robes, sat on a raised bench just twenty feet from the twenty-six defendants.

Judge Webb began the proceedings by saying, “There has been no more important criminal trial in all history.” He promised that to “their great task” the judges “bring open minds both on the facts and on the law.” The rest of the day, and part of the next, was consumed by an hours-long reading, in both English and Japanese translation, of the lengthy indictment. Each of the defendants rose to declare themselves “not guilty.”

The judges then listened to arguments challenging the legitimacy of the court and arguments that crimes against peace and crimes against humanity, two main charges in the indictment, were not in fact crimes at all under international law. They also argued that if the bombing of Pearl Harbor was murder (as charged in the indictment), then President Truman was equally guilty of murder for his authorization of the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. After deliberations, the judges could only agree to reject all the defense challenges for “reasons to be given later.” June 3 was set as the opening date for the trial.

Opening for the prosecution, Joseph Keenan said the trial was “a part of the determined battle of civilization to preserve the entire world from destruction.” Keenan recounted the history of Japanese aggression beginning with the invasion of Manchuria in 1931 through the end of the war. He said the prosecution would present evidence of massacres and tortures that included electric shock treatments, hanging prisoners upside down, prying fingernails, and horrible beatings.

Manchuria Phase

In the first phase of the trial, dealing with the Manchurian invasion, the prosecution called Japanese centrists who described their unsuccessful efforts to convince noisy nationalists and militarists within the government to abandon their plans to build a Japanese Empire in Asia, beginning with a takeover of Manchuria.

The prosecution’s Manchuria case was made difficult by the fact that almost all the evidence that could tie specific defendants to atrocities such as the raping and shooting of Chinese civilians was destroyed in the last days of the war. The fall of the Nationalist capital of Nanjing in 1937, and the shocking events that followed, was the heart of the prosecution’s China case.

IMTFE in session in 1946

Three Americans who had been working in Nanjing at the time testified. Robert Wilson, a Harvard-educated doctor, had been working at a hospital when the city fell. The surgeon described horrific injuries inflicted by the Japanese on patients entering the hospital, including the fatal burns of a man who had gasoline dumped on him and set aflame, the deep lacerations of a police officer who was the sole survivor of a group of men put up against a wall and machine-gunned, the vaginal wounds and syphilis suffered by a fifteen-year-old girl gang raped by Japanese soldiers. And on and on. In his letters home, Wilson described what he saw as “the modern Dante’s Inferno, written in huge letters with blood and rape.” Miner Bates, a missionary described what happened to two of his Chinese neighbors who objected after soldiers raped their wives: they were shot. He described unsuccessfully trying to pull soldiers away during acts of rape and estimated that 8,000 girls and women were raped just in the Safety Zone of Nanjing, a small portion of the city. Reverend John Magee, an Episcopal minister, described “passing columns of men taken out to be killed.” He described watching one Chinese man shot in the face at close range “with no more feeling than one taking a shot at a wild duck.” Several Chinese survivors also appeared as witnesses, adding their gruesome stories to the prosecution case of crimes against humanity. News reports suggested the Japanese public found the evidence of their troops atrocities distressing.

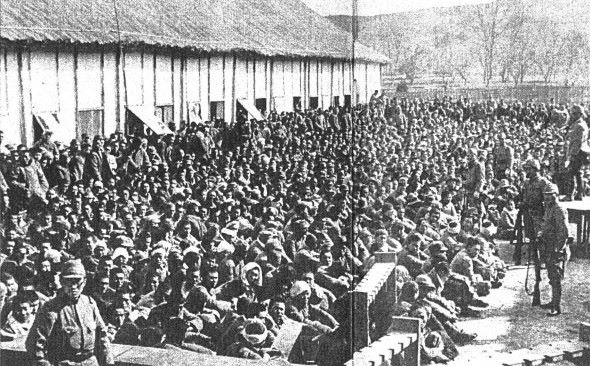

Chinese captives in Nanjing

The prosecution argued that the atrocities in Nanjing were so extensive, and the protests to the Japanese embassy so numerous, that senior officials in Japan had to know what was happening, yet they did little or nothing to stop it. The defendant most closely tied to the Nanjing atrocities was General Matsui Iwane.

Pearl Harbor Phase

In the phase of the trial focusing on the surprise bombing of Pearl Harbor, the prosecution introduced evidence of treaties and conventions that it claimed outlawed aggressive action such as seen in Hawaii in December 1941. The prosecution also presented evidence of am imperial conference in September 1941 in which Japanese leaders, hampered by a U.S. embargo on oil exports, agreed to wage war against the United States, the British Empire, and the Dutch Empire unless those Allies met certain stiff demands. (The Emperor, at this September meeting, made an effort to stop the war, even quoting an antiwar poem). After a second imperial meeting in November, Japanese leaders had all but given up on a diplomatic solution and began making preparations for war. On December 1, at a final imperial meeting, X-Day (the day for the bombing of Pearl Harbor) was set for December 7—with the approval of the Emperor.

Prosecutors showed that under the Hague Convention, hostilities must not begin until after a declaration of war. Although Japan had planned to notify the United States some minutes before the 7:55 a.m. attack, because of unanticipated delays, the Japanese ambassador did not provide actual notification until about an hour after the attack began.

War Crimes (Atrocities) Phase

Nearly one-third of all Allied soldiers captured by the Japanese died in captivity, compared to just 4% of Allied prisoners held in Europe. As historian Gary Bass noted in Judgment at Tokyo, Japan’s treatment of prisoners of war “was marked by incompetence, inexperience, and severity”—in the trial, prosecutors presented evidence that it was more than that: it was a purposeful and systemic mistreatment of prisoners in violation of the Hague Convention.

Several witnesses testified of the horror of forced work on “the death railway,” a 250-mile track construction project from Thailand through Burma, meant to open up a new war front. A captured American lieutenant in the medical corps testified that the relentless work in monsoon rains caused thousands to die of dysentery, bowel perforations, malaria, and other diseases. He told the court that on a single day he sawed off legs of 120 men suffering from leg ulcers.

A Canadian hospital chaplain testified that Japanese troops stormed a hospital in Hong Kong where injured Allied soldiers were being tended to. He testified the Japanese killed 170 soldiers, including 70 bayoneted to death in their beds.

Vivian Bullwinkel on the witness stand in the Tokyo War Crimes trial

An Australian nurse testified the Japanese bombed a ship which was evacuating army nurses and others from Singapore. When the survivors reached an Indonesian beach in life rafts, Japanese troops shot them. The nurse, Sister Vivian Bullwinkel, testified that she in a group of twenty-two surviving nurses ordered to march into the sea, where the troops opened machine-gun fire on them. Bullwinkel was shot in the wrist and carried by waves to a beach. She played dead until the troops left.

Several American soldiers testified about the “Bataan death march,” a seven-day, 65-mile forced march of prisoners along the Bataan Peninsula in the Philippines. During the march, between 500 and 650 Americans died, as well as 5,000 to 18,000 Filipino soldiers. Donald Ingle, an American soldier who was forced to march with a severely injured shoulder, was asked by the prosecutor whether he felt bitter towards the march leaders. “Well,” he replied, “there are several thousand buddies that aren’t here today that would be if it weren’t for that. Use your own judgment.” Witnesses testified about other atrocities in the Philippines, including entire villages being burned and an incident where 800 men, women and children were lured into a supposedly safe hall and then killed with dynamite. The diary of a Japanese soldier was introduced. In it, the soldier admitted to killing over a hundred Filipinos. The soldier was troubled by the violence he was ordered to commit: “Although it is for my country’s sake, it is sheer brutality. May God forgive me! May my mother forgive me!”

In the war crimes phase of the trial, along with the graphic testimony of witnesses, the prosecuted attempted with documentary evidence to tie the atrocities, using the chain of command, to various defendants. On January 24, 1947, the prosecution rested.

The Defense

After the prosecution completed its case, various defense lawyers rose to argue that even if all the prosecution evidence was assumed true, it still failed to prove guilt beyond a reasonable doubt for their clients, and they should be set free. Perhaps the strongest case was made by the defense lawyer for former foreign minister Togo Shigenori, who argued that the evidence showed Japan attacked the United States “in spite of, certainly not because of, Togo’s efforts.” Predictably though, all defense motions to dismiss charges were rejected.

The opening statement for the defense was made by Koyose Ichiro, who presented an alternative history of the war. In Koyose’s telling, Japan entered into war to protect the rights of Asians whose lives were controlled by the racist western colonialists who had carved up the continent. World War II, for Japan, was a war of self-defense. Americans were shocked by the bold defense. The New York Times called it “an impertinence.”

The defense case was a slog. Witnesses were called to deny various atrocities, or to blame the atrocities on low-level officers rather than the defendants, or to suggest that those responsible had been appropriately punished by senior officers. The defense tried to show some POW camps were run appropriately, but the camps they pointed to were small camps operated early in the war. When defense lawyers tried to present evidence that certain aggressions, such as the invasion of Manchuria, were undertaken to prevent the spread of Communism, judges cut off that line of questioning.

On September 10, 1947, in the final phase of the defense case, defendants took the stand to refute, as best they could, the charges against them. In some cases, this led to one defendant pointing a finger at another defendant, or a representative of one branch of government or the military pointing a finger at another branch. Defendants claimed they did nothing, or only obeyed orders.

Marquis Kido Koichi, the Emperor’s right-hand man, was largely considered (along with Tojo Hidecki) one of the two most important defendants on trial. The primary accusation against him concerned his role in the appointment in 1941 of the militant Tojo as prime minister. Kido tried to paint the appointment of Tojo as a necessary bowing to inevitable pressures building in the military and threatening civil war. On cross-examination, prosecutor Keenan asked, “You could not have found a much more belligerent individual in the entire Empire of Japan than Tojo on the 15th of October 1941, could you?” Kido replied, “I don’t think that criticism is just.”

Togo Shigenori sought through his testimony to show that he fought for peace, but lost. He testified that he opposed quitting the League of Nations, opposing forming an alliance with the Nazis, and opposed the invasion of Southeast Asia. While he joined others in declaring war on the United States, he said he did so reluctantly and “did not dream that the Japanese Navy would ever attack the American fleet in Pearl Harbor.” He added, “It is the great sorrow of my life that I was not successful in preventing war in 1941, but it is a matter of some consolation for me that I was able to contribute to the lessening of suffering of mankind by ending it in 1945.”

Tojo Hideki on witness stand in the Tokyo Trial, 1947

On December 26, 1947, came the moment in the trial that many had been waiting for: Tojo Hideki, the most famous defendant on trial, took the stand. A Time magazine reporter said he testified “with the cold assurance of a conquering samurai.” Tojo was unapologetic. He insisted that the war was necessary. His only regret was losing it. “I will contend to the last that it was a war of self-defense,” he said. Asked whether he was made the decision to bomb Pearl Harbor, Tojo replied, “Yes, I am responsible.” Somewhat surprisingly, Tojo insisted that the U.S. had advance knowledge of the attack in Hawaii, suggesting that the Roosevelt Administration was complicit in the deaths of U.S. soldiers. For the most part, Tojo stood his ground during the days of cross-examination and many western observers viewed his testimony as “a complete fiasco” for the Allies.

Summations, Verdict, and Sentence

Keenan, in his summation for the prosecution, argued that all of the defendants should be hanged. For its part, the defense argued that aggressive war was not a crime under international law and that punishing the defendants would be “nothing but lawless violence.” As for the many atrocities described by witnesses, the defense insisted the evidence did not tie them sufficiently to any of the accused. The Tokyo trial adjourned on April 16, 1948.

Writing an opinion, with a panel of eleven judges from different countries and each with strong views, was no easy task. Webb, the Australian chief judge, had a working majority that consisted of the British Commonwealth bloc of judges (Australia, New Zealand, Canada, Britain), the Chinese judge, the Philippine judge, the Soviet judge, and the American judge. The French and Dutch judges were less certain votes for across-the-board convictions and the Indian judge, Radhabinod Pal, was preparing a full-blown dissent. When the draft opinion was circulated, a final round of disagreement came down to sentencing.

Prisoners on transport from Sugamo Prison to courthouse

On November 4, 1948, the trial convened for the reading of the judgment and verdicts. Webb’s reading of the majority opinion went on for seven days. On November 12, Webb announced verdicts for each of the defendants. All twenty-five were found guilty on at least some of the charges. That included former foreign minister Togo Shigenori who had campaigned hard against the war. Historian Gary Bass called the verdict upon Togo “the most glaring injustice of the Tokyo trial.” When Tojo Hideki stood to hear his verdict, Webb said Tojo “bears major responsibility for Japan’s criminal attacks on her neighbors.” For his part, Tojo said “I can only say it is a victor’s trial.” After pronouncing verdicts, Webb said that “the member for India dissents from the majority opinion and has filed a statement of his reasons.” Webb added that the French and Dutch judges also had written dissents.

Judges (top bench) listen to counsel at the Tokyo trial

After a fifteen-minute break, Webb pronounced sentences for each defendant. Tojo Hideki and five other defendants were sentenced to death (on votes, it turned out, of 7 to 4 or 6 to 5 (Hirota Koki)). Tojo, after hearing that he would be sentenced to death by hanging, bowed to the court. All except two other defendants were sentenced to life in prison. The two defendants receiving the lightest punishments got terms of either 20 or 7 years. In prison awaiting his death, Tojo penned a haiku: “Oh, look, see how the cherry blossoms fall mutely.” Condemned prisoner Doihara Kenji also sent a poem to his children: “Born like a bubble of foam and to fade like the dew on the grass, my precious being.” In a letter, Tojo said he wished the judges had let him take sole responsibility. He expressed thanks, however, that the Emperor was spared.

The condemned prisoners spent their last days writing letters, reading, and playing cards. Their lawyers filed formal appeals to MacArthur to review their sentences, but MacArthur announced in a radio address that their death sentences would stand.

Sugamo Prison

American lawyers for two of the men filed a motion with the U.S. Supreme Court for a writ of habeas corpus, arguing that only Congress could authorize punishments and that the charges against their clients amounts to Ex Post Facto Clause violations. Surprising most observers, the Supreme Court voted 5 to 4 agreed to hear argument son the defense lawyer’s motion. Arguments before the Supreme Court took place over two days, December 15 and 16, 1948. Three days later, the Court announced its decision in Hirota v MacArthur. In a brief per curium opinion, the Court said that “the courts of the United States have no power or authority to review, to affirm, set aside or annul the judgments and sentences imposed.” Justice Frank Murphy dissented. Justice William O. Douglas wrote a concurring opinion arguing that the Court did have jurisdiction and expressing skepticism over some of the charges. In the end, though, Douglas viewed the question of what punishment is doled out to be a political question “in which the President as Commander-in-Chief has the final say.”

At 12:01 a.m., December 23, 1948, the executions began. American executioners led the first four prisoners to the gallows, fitted black hoods over their heads and placed ropes around their necks. After the call “Proceed!”, four trapdoors opened and the men fell. In thirty minutes, all seven prisoners were dead.

The United States decided not to press forward with additional international war crime trials. On the day after the executions, the nineteen remaining unindicted Class A criminals were released from prison and allowed to return to public life.

On April 28, 1952, in a ceremony in San Francisco, a peace treaty was signed formally ending the American occupation and restoring Japan as a sovereign country.

Beginning in 1950, paroles were granted to the defendants sentenced to prison terms. The final ten surviving parolees were unconditionally released in 1958.