The Nat Turner “Slave Revolt” Trials: An Account

by Douglas O. Linder (2020)

Nat Turner meets with his confederates before the revolt at Cabin Pond in Southampton County, Virginia

The most famous slave revolt in American history took place in a backwater Virginia county in August 1831. The revolt, led by a 30-year-old slave named Nat Turner, would lead to the deaths of over 200 slaves and free blacks, and about sixty whites. In the trials that followed the revolt, twenty-one participants, including Turner, would be sentenced to be hanged.

The Turner-led revolt profoundly affected the course of American politics. Many southern whites came to see the revolt as part of a larger Northern abolitionist plot. Their charges brought national attention to outspoken abolitionists such as William Lloyd Garrison. For the first time, major political leaders including the governor of Virginia, began suggesting that southern states consider secession.

On the other hand, some southern politicians saw the revolt as evidence that slavery came at too high of a cost and began arguing with emancipation or removal of all African-Americans from their states. They would lose that argument, of course. Instead, southern states passed laws strengthening militias, banning large gatherings of slaves in churches and elsewhere, banning “anti-southern” books and literature, and eliminating slave schools. Southern states determined to make sure that such a revolt could never happen again. The response of the southern states to the Turner Revolt was to dig in—a response that inevitably set America on course for the Civil War. The Turner Revolt was a highly consequential event in our history.

The Evolution of Nat Turner

Nat Turner’s childhood seems to have been—for slaves in the antebellum South—a pleasant one. He was raised on the tobacco, corn, and apple farm of Benjamin Turner in Southampton County, Virginia. The Turner family were prominent Methodists, and held Sunday services for their thirty-or-so slaves, and took them to Sunday chapel. Nat played with the Turner children, and was especially close to John Turner, one of his master’s sons who was about his age.

Nat was precocious. His reading and writing skills amazed everyone. Stephen Oates, in his history of the Slave Revolt, describes Nat as “a source of wonder around the Turner neighborhood.” He also, as he grew into a young man, was different, more serious than his friends. He didn’t drink alcohol, swear, steal, or play practical jokes.

Life changes came quickly and usually without warning for many southern slaves, and Nat was no exception. His father escaped from the Turner farm and headed north to freedom. Nat never saw him again, but he remained an important figure in his life. In 1809, Nat and his mother, as well as six other of Ben Turner’s slaves were loaned to Ben’s son Samuel, a young bachelor. Samuel was less forgiving, and a harsher taskmaster, than his father.

In 1812, at the age of twelve, Nat was required to begin his life of back-breaking work. He milked cows and fed hogs before dawn, and worked the fields until dusk. He and other slaves planted cotton in March, stripped tobacco leaves from stalks in August, picked cotton in October. In between, they hoed, grubbed, chopped firewood, and repaired fences. Slaves had Sundays off, plus four holidays a year.

Young Nat spent a lot of time thinking about religion. He began to hear “the Spirit” call out to him. He began to believe, as he later said, “I was ordained for some great purpose in the hands of the Almighty.” He took his assignment seriously, and began memorizing the books of the Old Testament.

By the time he reached 21, Nat was consciously working on his image as a prophet. To others, he seemed aloof and mysterious. Nat said, “Having soon discovered to be great, I must appear so, and therefore studiously avoided mixing in society, and wrapped myself in mystery, devoting myself to fasting and prayer.”

Nat took to spreading word of his connections with the Spirit among his fellow slaves, in both the fields during the day and the cabins at night. Many began to see Nat as a holy man, a man capable of miracles. Nat told friends that something big was going to happen—something that would be fulfillment of “the great promise made to me.”

In 1821, a new and more severe overseer at the Samuel Turner farm flogged Nat for some unknown reason. Nat responded by running for the swamps, but returned freely to the farm thirty days after his escape. Nat said later “The Spirit appeared to me . . . and said that I should return to the service of my earthly master.” He settled briefly back into slave life, and married a young slave girl named Cherry.

The next year, Samuel Turner died. Nat and Cherry, and the other Turner slaves and property, went to auction. Nat was sold for $400 to a farmer named Thomas Moore; Cherry to another nearby slave owner. Work on Moore’s 720 acres was harder than it ever had been at the Turner farm.

Nat Turner read and reread the Bible. In 1825, Nat thought hard about the meaning of a verse in Exodus: “And he that stealeth a man, and selleth him. . . shall surely be put to death.” Exodus tells the story of Moses, leading his people to the promised land. Nat began to think of himself as a modern-day Moses, a prophet who might lead his people, black people, to a better future. Nat reported having apocalyptic visions around this time: “I saw white spirits and black spirits engaged in battle.” He saw “the sun and sky darkened” and “blood flowing in streams.” One day he saw blood on corn; another day he saw leaves with hieroglyphic characters etched on them. He felt called to preach, to spread his message, in praise meetings at black churches and meeting houses. His master, Thomas Moore, considered his religious obsession harmless. By 1826, Nat was identifying blacks he could trust, and began preparing them for what he called “his mission.”

In 1828, Nat received from the heavens what he considered a clear sign of what he was called to do: “The Spirit instantly appeared to me and said that the Serpent was loosened . . .and that I should take it on and fight against the Serpent, for the time was fast approaching when the first shall be last and the last should be first.” It was his job, he concluded, “to arise and prepare myself, and slay my enemies with their own weapons.” Nat was bold enough to tell his master that slaves should be free and, “one way or another” would be some day. For that suggestion, Nat received a beating in the shed.

Later that year, Thomas Moore died, and Nat became the legal property of his nine-year-old son, Putnam Moore. The next year, Sally Moore remarried and her new husband, Joseph Travis, took command of seventeen slaves, including Nat. Nat considered Joseph a kind master.

Although slave revolts had occurred elsewhere, including a planned attack in 1822 in Charleston conceived by Denmark Vesey that led the execution of thirty-five conspirators (including Vesey), Southampton whites thought Virginia in general, and their county in particular, was virtually immune from such troubles. Compared with other slave states, Virginia’s laws were relatively permissive. Virginia slaves, the thinking went, were happier than slaves elsewhere.

Nat Turner’s Slave Revolt

An 1831 eclipse of the sun was taken by Nat as a sign that the time had come for action. He identified four trusted slaves—Hark, Henry, Nelson, and Sam. They would be his lieutenants. Nat took on the title “General Nat.” Nat and his four lieutenants put together a list of other slaves that could be counted on when the insurrection commenced.

On Saturday August 13, as Nat described it later, “a black spot passed over the sun.” To him, this could only mean “so shall the blacks pass over the earth.” It was now time to move. Word began to circulate among slaves in Southampton county that something momentous was about to happen, and that General Nat was behind it.

On the afternoon of Sunday August 21, Nat and his lieutenants gathered at Cabin Pond, deep in the Southampton County woods. They made final plans. The killing would began that night. Nat expected that once the insurrection began, slaves and free blacks all over the county would join the cause.

They set out, carrying a torch, shortly after midnight towards the Travis farm. When they came out the woods, they put out their torch and made their way across the fields Nat had long labored in. After some drinking at the farm’s cider press, and wielding axes, they headed to the house. Nat entered through a second-story window and unbarred the door. Nat and a trusted recruit named Will surprised a sleeping Joseph Travis and his wife in their bedroom. Will hacked both to death, the first victims of the Turner Slave Revolt. Within minutes, five other whites in the house, including an infant in its cradle, were slaughtered.

The home of Catharine Whitehead, where Nat beat to death Margaret Whitehead

The bloody pattern was repeated at farm house after farm house that night. Near sunrise, at the plantation of Wiley Francis, the band of fifteen insurgents encountered serious resistance and, instead of fighting, moved on to their next target. The killing at Caty Whitehead’s farm was especially violent, with a preacher axed to death, followed by the butchering of three Whitehead girls and a grandchild. It was at the Whitehouse farm that General Nat committed his only murder with his own hand, beating Caty’s daughter Margaret to death with a fence rail over he overtook her, fleeing through a field.

Nat killing Margaret Whitehead

Margaret’s sister Harriet escaped. She was found later by a search party in the woods, muddy and bug-bitten, and brought to the settlement of Cross Keys. There, Harriet shocked people with her tale of blood and gore.

Harriet’s story added to the general alarm that was spreading among whites in the county. Initial reports had come in from slaves who witnesses the massacre at the Travis and Francis homes. Another alarm was sounded by Choctaw Williams, who had seen the bloody decapitations at the Whitehead plantation and raced on a horse, south to Murfreesboro, North Carolina, to alert the state’s Guards. Meanwhile, Nat and his now mounted band of about forty men, continued their gruesome work.

By Monday morning, barricades were going up around Southampton County, with rumors circulating that an army of five hundred bloodthirsty slaves was on the march. Calls for help were sent to Richmond and other population centers. In the afternoon, two parties of armed whites set out in pursuit of the insurgents.

With word of the insurrection spreading, Nat and his small army (now about sixty or seventy men) found more and more homesteads abandoned. But killings continued. At the farm of Jacob Williams, the overseer was disemboweled, and Jacob’s wife and three children murdered at well. At Rebecca Vaughan’s house, Rebecca and her eighteen-year-old niece were shot, and her son and the farm’s overseer slaughtered. By noon on Monday, the death toll of whites reached about sixty.

Rebecca Vaughan home, scene of the last massacre in the slave revolt

Nat planned to march to the village of Jerusalem and seize whatever weapons and ammunition they could find. Near the place of James Parker, the slave army encountered a party of armed white men. In the ensuing fight, a half dozen of Nat’s men were injured, and Nat ordered a retreat into the forest.

By Tuesday, whites were mobilizing all over Virginia and northern North Carolina. Volunteer units from places such as Norfolk and Petersburg, and federal forces from Fort Monroe, headed toward Southampton County. The Governor’s Guards from Murfreesboro, North Carolina moved north. Meanwhile, the number of insurgents dwindled, both from injuries and slaves sensing the tide was turning against them and abandoning the cause. Only about twenty remained.

In a desperate attempt to rally more slaves to fight, the insurgents headed to the plantation of Dr. Simon Blunt. Whites were waiting for them. A volley of shots erupted, and when the skirmish was over several slaves lay dead. Nat and four others managed to escape into deep woods. Nat dug a hole in a pile of fence rails near Cabin Pond, dug a hole, and crawled in. “To lie by till better times arrive,” he later said.

They would never come. The killing of whites was over, the killing of blacks had just begun—not only slaves who participated in the insurrection, but many others as well who were only suspected of being sympathizers. And some, it seems, were killed simply because they were black. A cavalry unit from Murfreesboro decapitated fifteen slaves and put their heads on poles. They would remain there for weeks. The exact number of blacks killed in the days following the insurrection is not known, but probably exceeds 120.

By August 28, most of Nat’s army was either locked up in a wooden jail in Jerusalem or dead. Only Nat and five or six followers remained at large. Nat, by this time, had been determined to be the leader of the slave revolt. Everyone was looking for him.

The Trials

A Court of Oyer and Terminer met on August 31 in Jerusalem (called Courtland now) to begin trials of forty-nine blacks imprisoned for their alleged roles in the revolt. No jury was present. The fate of the prisoners would be decided by justices appointed by the governor and his council. Virginia Governor John Floyd insisted that the trials follow the letter of the law and the transcripts be authenticated by the sheriff.

Eight slaves faced arraignment on August 31. Local lawyers were appointed to defend them. Perhaps the best argument defense lawyers could make for their clients was a financial one. Under Virginia law, the state had to pay slave owners for each executed slave.

Even so, sentiment being what it was, the odds were stacked against the defendants. The justices convicted several slaves despite evidence that they participated in the insurrection against their own will, even at gunpoint. (Three convicted teenage slaves, who mounted a failed duress defense, had their sentences later commuted by the governor, and were transported outside of the United States.) Other slaves were convicted simply for voiced their support for the insurrection.

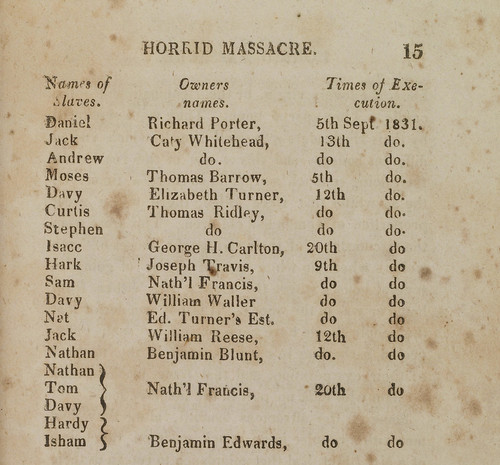

On September 3, three of Nat’s most trusted recruits—Sam, Hark, and Nelson—came up for trial. In the case of Hark, the prosecution relied on both eyewitness testimony and the testimony of Thomas Ridley, who interrogated Hark after his capture, to secure a conviction. The judges sentenced Hark to death and ordered the state to pay the Travis estate $450 for their executed slave. Death sentences were also handed down the same day for Sam and Nelson, as well as two other slaves who participated in the revolt. The governor, after examining the trial record, approved the sentences, and all five were hanged on September 9.

With thirteen defendants convicted in the first fourteen trials, Nat Turner still had not been apprehended. On September 17, Governor Floyd issued a proclamation declaring a $500 reward for his capture. Rumors abounded as to Nat’s whereabouts, with reports that he’d been found drowned, escaped to the West Indies, and spotted in Washington D. C., or was in hiding in Ohio. None was true. Nat was still holed up in Southampton County, near Cabin Pond.

In late October, hungry and desperate, Nat decided to give himself up o Nathaniel Francis, who he had grown up with and played with as a young boy. Nat assumed that Nathaniel would treat him with respect, more as a prisoner of war than as a murderous criminal. Instead, when he came out from behind a fodder stack to surrender, Nathaniel shot at Nat, blowing his hat off his head. Nat fled, but word as to his whereabouts was now out, and within an hour, fifty armed whites were in pursuit.

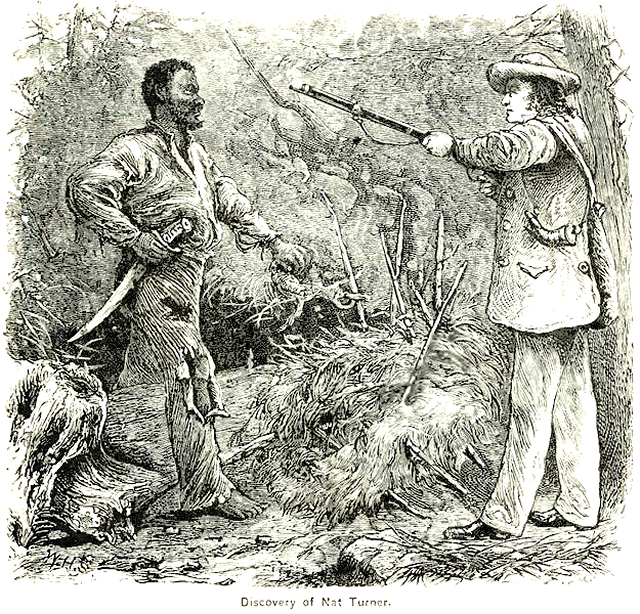

Nat was captured after a poor farmer named Benjamin Phipps spotted him poking his head out from a dug cave two miles from the Francis farm. A shotgun pointed at his head, Nat threw down his sword and surrendered. A small army of white men marched Nat down to Cross Keys. Along the way, he was spat at by angry whites and, at one point, whipped by his guards.

On October 31, Nat was taken to Jerusalem and arraigned by two justices. Nat told the judges he was ready to tell his story. For two hours, in the Jerusalem courtroom, Nat answered questions with complete candor. He said that the idea of an insurrection had been evolving in his head for several years. He talked about the signs he saw, the visions he had, what the Spirit had told him. He said only five or six people knew about his plans before the insurrection began. He said he ordered the slaughter of the whites. He admitted to personally killing Margaret Whitehead. He described massacres in grisly detail. “Indiscriminate massacre” was necessary at first, he said, to create terror. But, once the revolt was underway, he had planned to spare women and children and others who “ceased to resist.” He said he would too it all over again.

Southampton County jail, where Nat was held awaiting trial

Reporting on Nat’s confession, Postmaster Trezevant said that Nat answered questions “clearly and distinctly, and without confusion or prevarication.” He also appeared to be, he wrote, in “as perfect a state of fanatical delusion as ever wretched man suffered.” (Trezevant published his account in the American Beacon. The postmaster’s account is not completely accurate, as he intended it both as reassurance to whites that the troubles were past, and a warning to slaves to not try something similar in the future. For example, Trezevant reports that Turner said he had “done wrong” and urged blacks “not to follow my example.” Nat said no such thing.)

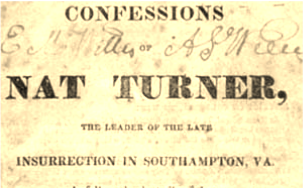

Turner’s trial was set for November 5 and he taken to the county jail. The next day, attorney Thomas Gray, who had defended several other slaves, visited Nat in jail. Gray asked Nat if he was willing to provide a full account of the insurrection that had shaken the South from to bottom. He told Nat that swirling rumors and exaggerated reports were resulting in the murder of dozens of blacks, and that telling his full story might help bring an end to the senseless violence. Nat saw it, apparently, as his chance to explain himself and set history straight. And so he agreed to talk.

The resulting account would be published later as “The Confessions of Nat Turner.” In it, Nat goes back “to the days of my infancy, and even before I was born.” He described his education, his love of reading, his family, his work life, and his growing sense of being chosen by God for a mission. He was unapologetic about what he’d done, comparing his coming execution to Christ’s crucifixion. He told Gray “I am willing to suffer the fate that awaits me.” The conversation between the two men went on for two days and left Gray impressed. He called Nat Turner a man “whose name has resounded throughout our widely extended empire.” His account was sincere and consistent with all known facts. But Gray considered him also “a complete fanatic,” and said his description of killings caused his “my blood to curdle in my veins.”

A large crowd was on hand for Nat’s trial. Deputies escorted Nat from the jail to the courthouse. Presiding Judge Jeremiah Cobb gaveled the session to order. The clerk of court read the charges: “Nat alias Nat Turner a Negro man slave the property of Putnam Moore the infant is charged with conspiring to rebel and make insurrection.”

The first witness for the prosecution was Levi Waller. Waller described the murder of several of his own family members. He testified that Nat was clearly in command and directed the actions of the actual killers. Postmaster James Trezevant was the next witness. He repeated the words of the confession Nat had made in court during his arraignment. He also noted that Nat had given a longer, and much more detailed confession in jail, which the clerk then read in court. Nat acknowledged that the confession was accurate and freely given.

It was an open and shut case. There was little his attorney, James Parker, could do. He submitted the case without argument.

Judge Cobb, speaking for a unanimous court, pronounced Nat guilty as charged. He asked Nat if he wished to make a statement before sentencing. Nat replied, “Nothing but what I’ve said before.” Judge Cobb sentenced Nat to be hanged by his neck until dead on November 11. He ordered the state of Virginia to pay the Putnam Moore estate $375, Nat’s value as a slave.

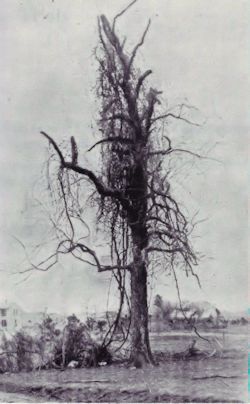

The tree from which Nat Turner was hanged

In a field northeast of Jerusalem, a huge crowd gathered to watch the execution of Nat Turner. The sheriff led Nat to an old tree that served as the local gallows. He asked Nat if he had any final words. “I’m ready,” is all that Nat said. Nat stared across the crowd and into the skies above—before he was pulled upward with a jerk of the rope.

Nat’s wife and daughter were sold to slave traders. One of Nat’s two sons is believed to have remained in Southampton County. The other, according to black tradition, made his way to freedom in Ohio.

What to make of the short and strange life of Nat Turner? Nat fought for a worthy cause, but he was no hero. Heroes don't beat girls to death or order the killing of infants. Nat Turner was a religious fanatic--and like many other fanatics, he let his fanaticism overcome his basic humanity. Good ends do not justify all means.