The Two Ulysses Trials: An Account

by Douglas O. Linder (2020)

James Joyce in 1922, the year Ulysses was first published in France

It is the most infamously obscene book in ancient or modern literature….All the secret sewers of vice are canalized in its flood of unimaginable thoughts, images and pornographic words. And its unclean lunacies are larded with appalling and revolting blasphemies directed against the Christian religion and against the name of Christ—blasphemies hitherto associated with the most degraded orgies of Satanism and the Black Mass.

–U. S. Attorney Martin Conboy, quoting James Douglas's comments about Ulysses in the London Sunday Express, in argument before the 2nd Circuit Court of Appeals in U. S. v One Book Enittled Ulyssses (5/16/1934)

Ulysses began in the mind of James Joyce in 1906 as an idea for a short story. He thought it clever to attach a Homeric-style name to a drunk he met one night in Dublin. Ulysses’ story, unlike the journey of Homer’s Odysseus, would be anything but heroic--the thoughts and ramblings of a near-middle aged, somewhat pitiable, Irish advertising salesman as he traveled around Dublin one late spring day. But the short story would become a novel, and it grew and grew over the course of 15 years of writing by Joyce in Trieste, Zurich, and Paris to a total of 732 pages in notebooks and on sheets of paper.

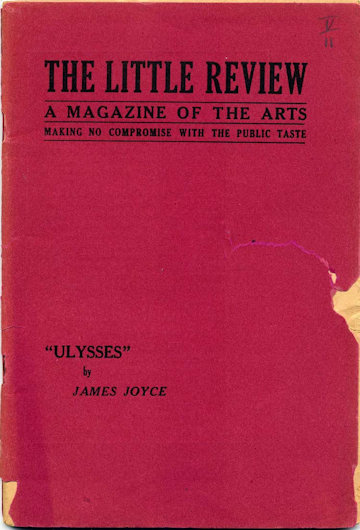

Some contemporary writers, such as T. S. Eliot and Ernest Hemingway, called Joyce’s modernist epic a masterpiece. But others just called it obscene. Before Joyce could declare a final victory, his book would be the subject of two obscenity trials in the United States. The first resulted in the criminal conviction of two daring publishers of the literary magazine The Little Review. The publishers were ordered to seize and desist publishing episodes of Ulysses, and existing copies held by the post office were burned. The second, which effectively gave Random House the greenlight to publish Ulysses in the United States, also produced a landmark opinion—an opinion which undid a repressive obscenity test which had stood for more than half a century and replaced it with one which allowed serious writers to tell stories with candor, realism, and honesty. Ulysses changed the course of literature.

The story of the Ulysses trials brings together literary geniuses, bold publishers, puritanical crusaders determined to protect the public from impure thoughts, crafty lawyers, and one of the most celebrated jurists in American history. As Molly Bloom might say: Yes!

Joyce Finds a Publisher

Margaret Anderson decided she would publish a cutting-edge literary magazine with a feminist bent. Her lively intellect, persistence, and striking beauty all served her well in pulling together funding for her venture. She secured promises of ads from publishers like Scribner’s and Houghton Mifflin, as well as donations from modernist intellectuals, including $100 from architect Frank Lloyd Wright.

Margaret Anderson, publisher of The Little Review

In the inaugural 1914 quarterly issue of The Little Review, Anderson declared her magazine a place for “untrammeled liberty which is the life of Art.” She added, we are done with letting “husbands, fathers, and brothers decide for us what is best to do.” Two years after its debut, Anderson brought to the Review’s offices a kindred spirt in Jane Heap, who had fled the prairies of Kansas to join the Chicago theater scene. In Anderson’s words, “Jane and I began talking. We talked for days, months, years” and formed a “consolidation that was to make us much loved and even more loathed.”

A published complaint by Anderson concerning the quality of recent submitted manuscripts, produced a response from the poet Ezra Pound, who wrote to suggest that a place be set aside in each issue where he and T. S. Eliot might appear regularly, and where “Joyce can appear when he likes.” Pound told Anderson that if the space could be set aside, he knew of a “Mr. X” who agreed to provide funding of $750 a year for himself and the other writers he promoted. The “Mr. X” turned out to be lawyer and art and manuscript collector John Quinn—the lawyer who, for better or worse (mostly worse), would defend Anderson and Heap in the criminal obscenity trial which was to come. Pound and Quinn had first met in 1910 at Petitpas', a French restaurant and boardinghouse in the Chelsea district of Manhattan, which was a regular gathering place for poets. John Butler Yeats introduced the two men.

Yeats at Petitpas' by John Sloan (1914)(Yeats is second from right)

In May 1917, Anderson accepted Quinn’s financial support and appointed Ezra Pound foreign editor of the Review. Pound secured for publication 21 poems from W. B. Yeats and eight from T.S. Eliot. But the biggest prize secured by Pound were episodes of Joyce’s ever-growing, evermore mystifying novel, Ulysses. In December, Joyce began sending episodes to Pound, who passed them along to Anderson. Pound knew Joyce’s material well and was aware of the risk of prosecution. “I suppose we’ll be suppressed if we print the text as it stands,” he wrote Joyce, “BUT it damnwell worth it. I see no reason why nations should sit in darkness merely because Anthony Comstock was horrified by the sight of his grandparents in copulation.” (Anthony Comstock was an anti-vice activist, United States Postal Inspector and secretary of the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice.)

Anderson loved Joyce’s first episodes. “This is the most beautiful thing we’ll ever have,” she told Heap. “We’ll print it if it’s the last effort of our lives.” She announced in the January 1918 issue of The Little Review that the magazine was “about to publish a prose masterpiece.”

Ezra Pound (far right), John Quinn (standing), and James Joyce (far left)

Between 1918 and 1920, eleven chapters (“episodes”) of Ulysses were serialized in The Little Review. John Quinn was not among the book’s fans. He referred to the first episode as “the Joyce thing” and dismissed later episodes as “toilet-room literature” that would be “subject … to damnation in thirty seconds by any court or jury.” Not exactly the support you might want from your attorney. Quinn announced he would no longer provide financial support for the Review and in an October 1918 letter to Pound, referring to Anderson and Heap, said, “They can go to hell as far as I’m concerned.”

Postal authorities began taking a hard look at Joyce’s contributions to The Little Review. Whether because of a complaint or on his own action is unclear, but the Postmaster decided to suppress the January 19 issue of the magazine containing Joyce’s seventh episode, Lestrygonians. It appears the Postmaster was most moved to act by a passage in which Joyce has Leopold Bloom, one of the book’s two main protagonists, remembers his first sexual encounter with his wife, Molly: "Wildly I lay on her, kissed her: eyes, her lips, her stretched neck beating, woman’s breasts full in her blouse of nun’s veiling, fat nipples upright. Hot I tongued her. She kissed me. I was kissed. All yielding she tossed her hair. Kissed, she kissed me."

The next issue of The Little Review was also suppressed, although it is not clear why. Anderson had taken the precaution of excising a description of the protagonist Stephen Dedalus pissing on his doorstep and a couple of lines in a ballad referring to masturbation. The lack of obviously erotic material in episode 8 led Quinn, at the request of his clients, to file a memorandum with the Solicitor of the Post Office arguing against suppression of the issue. The Solicitor replied that the suppression was based “on the magazine as a whole.”

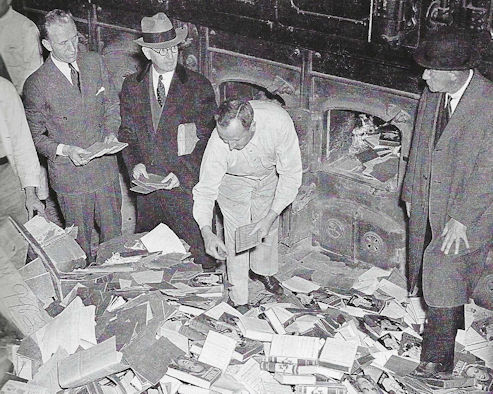

Undeterred, The Little Review continued to publish additional chapters from Ulysses until January 1920, when the entire issue was seized and burned by the Post Office based on Joyce’s words in the Cyclops episode.

Anderson said the burning of her magazine felt “like a burning at the stake.” She wrote about her “excitement of anticipating the world’s response to the literary masterpiece of a generation” and then, instead, receiving a notice from the Post Office: “BURNED.”

The First Ulysses Trial (The Criminal Trial of Margaret Anderson and Jane Heap)

The Nausicaa episode published in the July-August issue of the Review finally prompted authorities to file a criminal complaint against Anderson and Heap for violating New York’s obscenity law. The episode includes a scene at a beach strand where an 18-year-old girl named Gerty MacDowell is sitting on a rock, dreaming about men. Leopold Bloom observes her, becomes sexually excited as she arches back, and masturbates. The description is not terribly graphic, but leaves little doubt as to what is happening. Bloom recomposes his shirt, then thinks: “Did she know that I? Course. Lord, I am wet. For this relief much thanks.”

John Sumner, successor to Anthony Comstock as secretary of the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice, thought Bloom’s masturbation session was beyond the pale and filed a complaint. Anderson and Heap were charged with illegally distributing “obscene, lewd, lascivious, filthy, indecent, or disgusting” material.

John Sumner (in hat) presiding over a book burning in 1935

Under the prevailing obscenity test, dating back to the 1868 English case of Regina v Hicklin, courts focused on the most allegedly obscene or filthy portions of the work, and considered their possible effects on the most susceptible of readers, and did not bother to consider whether the work as a whole had serious literary merit or even whether the average reader would find the identified passages to incite lust. If Hicklin was the test, Anderson and Heap were in trouble, and their attorney, John Quinn, knew it.

While Anderson and Heap faced an uphill battle, Quinn made it even worse for two reasons. First, he had a conflict of interest. He believed that conviction of his clients, and an end to the serialization of Ulysses, would be great publicity for what he imagined might be an expensive private edition of the finished book, presumably for experts in literature—and that a private edition would be less likely to attract the attention of censors and prosecutors. Second, he didn’t really believe in either his clients or their cause. In private letters, Quinn referred to Anderson and Heap as having “the perverted courage of the bugger and the lesbian,” and described The Little Review as “a sewer that covers [its contents] with common stench and filth.”

Quinn, his heart not really in the battle, did not make the potentially stronger argument that Ulysses was great literature, presented life and thoughts realistically (what John Butler Yeats called Joyce’s “terrible veracity”) and, taken as a whole, was not a book likely to incite lust. Instead, Quinn argued in a pre-trial hearing that Joyce depicted sex in a filthy, non-erotic sort of a way and, therefore, the book was more likely to deter immoral behavior than encourage it.

The Little Review trial opened in February 1921. When the prosecutor was about to read the allegedly obscene passages, one of the three judges trying the case suggested, paternalistically, that it might be appropriate to excuse Anderson and Heap from the courtroom so they might be protected from the shock of it. But Quinn pointed out that the women were, after all, the publishers of the offending passages and had a right to hear the prosecutor read them.

Quinn changed his approach in the trial from that employed in the previous hearing, and argued less that Ulysses was disgusting, and therefore not likely to corrupt, and more that the book was simply so incomprehensible that few will read it, and even fewer will understand it. In a letter to Joyce, Quinn explained his strategy as the only one having any chance of success in a trial before “three stupid judges.” Moreover, Quinn argued to the judges, if a reader does make sense of the book it is likely to make him angry, not lustful. Quinn said: "That’s what Joyce does. That’s what Ulysses does. It makes people angry. They want to break something. They want somebody to be convicted. They feel like prosecuting everybody connected with it, even if they don’t know how to pronounce the name 'Ulysses.' But it doesn’t drive them into the arms of some siren. And, after all, it isn’t a crime to make someone angry."

The judges laughed and seemed amused by Quinn’s rather surprising argument but, in the end, it did not persuade them from finding Anderson and Heap guilty as charged. They were each fined $50 and were ordered to publish no further installments of Ulysses in The Little Review. Quinn said that he would not appeal.

In a short note on the last page of the next issue of The Little Review, Jane Heap noted the defeat. “We limp from the field,” she wrote.

The Second Ulysses Trial: The United States of America v One Book Entitled Ulysses

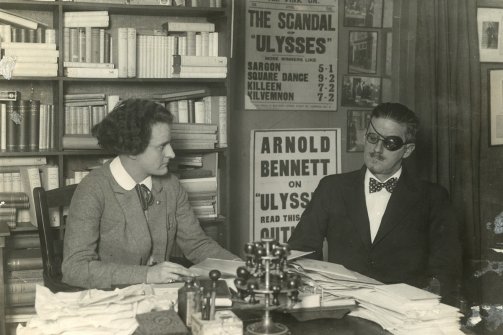

With publication in the United States not possible, James Joyce accepted the offer of Sylvia Beach to publish Ulysses in France under the imprint of her own bookstore, Shakespeare and Company. The book came off the presses in Paris on February 2, 1922, Joyce’s fortieth birthday.

Sylvia Beach and James Joyce in Paris

In 1926, a publisher named Samuel Roth (later a defendant in a landmark 1957 Supreme Court obscenity decision) began published unauthorized and expurgated installments of Ulysses in his magazine, Two Worlds Monthly. Joyce launched a publicity campaign to stop the unauthorized publication of his work, enlisting in his protest such figures as Virginia Woolf, T. S. Eliot, W. B. Yeats, Bertrand Russell, and Albert Einstein. Joyce followed that up with a lawsuit he filed in New York, alleging that Roth had violated his “right of publicity” under New York law. Roth had neither the will nor the money to contest the suit, and consented to an injunction against further publication of Ulysses.

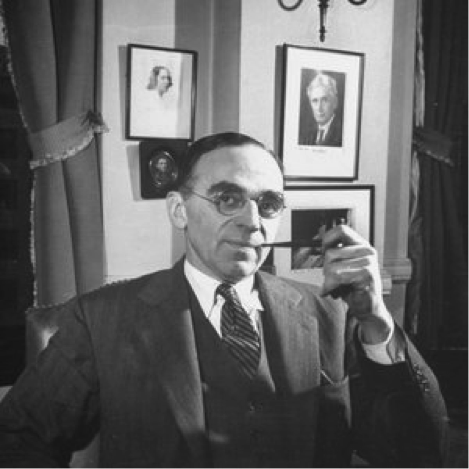

Bennett Cerf was the founder of a new publishing company called Random House. He was looking for an opportunity to attract attention to Random House and better compete with bigger, more established companies. He saw in Ulysses an opportunity. If he could somehow work his way around the obscenity problem, publishing an epic and controversial novel like Ulysses would make the splash we was looking for.

Cerf reached out to a respected veteran of dirty book battles, Morris Ernst, general counsel to the American Civil Liberties Union. Ernst admired Joyce’s work and jumped at the chance to help Cerf navigate through choppy obscenity works and bring Ulysses safely to the United States. He agreed to take the case in exchange for a 5% of any sales of the book.

Morris Ernst

Ernst knew the law and how to use it to his client’s advantage. He saw the Tariff Act of 1930 as providing the best opportunity to bring Ulysses to publication. The Act allowed customs agents to seize obscene books and magazines at points of entry and incinerate them. Because the Tariff Act was federal law, the case would be heard in federal court, where the hope for a sympathetic judge tended to be greater than in state courts.

To create a Tariff Act case, it first became necessary to have the Customs Bureau seize a copy of a book sent from France to Random House. The defendant, in a Tariff Act case, is not a person, but rather the object seized. So the case would become United States of America v. One Book Entitled Ulysses.

Bennett Cerf, publisher of Random House

Cerf grabbed a boat to Europe and met with Joyce and his French publisher, Sylvia Beach. Once Cerf and Joyce reached an agreement on rights and royalties, Joyce’s assistant, Paul Leon, bought a copy of Ulysses from Shakespeare and Company in Paris, and arranged to have a willing accomplice carry the book across the Atlantic on the steamship Bremen. Ernst arranged to have the carried book packed with glowing reviews of Ulysses, making sure that all those reviews would then become part of the evidence in any upcoming trial.

Ernst had an associate in his firm contact a lawyer in Customs to let them know that Ulysses was on its way and would be arriving soon on the Bremen at Brooklyn’s North German/Lloyd piers. Unfortunately, Customs officers made no attempt to seize the book; Leon’s confederate marched right through the Customs checkpoint and delivered book, unwanted, directly to Random House’s office. When Ernst inquired as to what went wrong, a customs agent said, “Everybody brings that in. We don’t pay any attention to it.”

Ernst took the book back to the Brooklyn pier and demanded that it immediately be seized. It took some effort by Ernst, but eventually the agents agreed that the book was dirty enough to seize. More months later, the Brooklyn customs office turned Ulysses over to an assistant U. S. Attorney. Finally, more months went by as assistant U.S. attorney, Samuel Coleman, completed the task of reading the book, then weighing whether to bring charges. Coleman had mixed feelings about filing charges. He called the book “a literary masterpiece.”

A masterpiece maybe, but one with some very dirty passages. The U.S. Attorney’s office eventually filed suit.

Ernst did not want a jury trial. He thought his prospects were better before a single judge. Ernst knew the judge he wanted to try the case, and he got him. It took some clever maneuvering, but Ernst succeeded in getting the case on the docket of Judge John Woolsey, a judge with a reputation of being skeptical of obscenity claims. Woolsey, a graduate of Yale University and Columbia Law School, read the entire 732-page book—and he read it carefully and critically. He also prevailed upon two “friends” (both fellow members of his letters and fine arts club) to be “literary assessors” and read the portions of Ulysses that prosecutors said crossed the line into illegal obscenity.

Judge John Woolsey

Particular attention was paid to the eighteenth and final chapter of the book, called the “Penelope” episode or, more commonly, “Molly’s Soliloquy.” Joyce himself admitted that Molly’s monologue was “probably more obscene than any preceding episode.”

Molly’s soliloquy comes at the end of the day detailed in the book, June 16, 1904. Lying in bed, next to her sleeping husband, Leopold Bloom, Molly’s mind wanders from her childhood in Gibraltar to past sexual encounters to the day she first made love to her husband.

A few phrases pointed to by the government suggest the rather graphic images running through Molly’s early morning brain in her Dublin bed:

“he must have come 3 or 4 times with that tremendous big red brute of a thing he has I thought the vein or whatever the dickens they call it was going to burst” ... “better for him to put it into me from behind the way Mrs Mastiansky told me her husband made her like the dogs do it and stick her tongue as far as ever she could”... “I’ll tighten my bottom well and let out a few smutty words smellrump or lick my shit or the first thing that comes into my head.” There are many additional such passages, with either descriptions of sexual activity or four-letter words.

In his brief, Morris Ernst highlighted the cultural significance and literary quality of Ulysses. He included positive reviews of the book from well-known authors such as F. Scott Fitzgerald and Theodore Dreiser. He included reviews of the book printed in major newspapers. He noted it was on a reading list for a course taught at Harvard by T. S. Eliot. He attached a map of the United States showing libraries that had indicated an interest in obtaining copies of the book.

He also argued that the book was simply too challenging for anyone intent on arousing his sexual interest to pick up. He wrote in his brief, Ulysses “is far too tedious and labyrinthine and bewildering for the untutored and impressionable who might conceivably be affected by it. Such people would not get beyond the first dozen pages.” To buttress his point, he included a list of obscure words Joyce used in the book, including hebdomadary, loodheramaun, strandentwining, hoyhnhnm, entelechy,a nd yogibogeybox. He also offered up a couple of particularly incomprehensible Joyce paragraphs. He added that Joyce’s stream-of-consciousness method “would discourage and repel rather than attract the average reader.”

As for the sex, Ernst argued that the topic “is relegated to a position of relative unimportance. As a matter of actual content it represents an insignificant part of the book.” The book, said Ernst, should not “be judged on the basis of isolated passages”—even though it does “contain occasional episodes of doubtful taste.” (Ernst downplayed the sex a bit; Joyce’s book does reveal that the author saw sexual desire as central to human lives.)

Ernst in the courtroom

In his hour of oral argument to the judge, Ernst tried to justify Joyce’s use of four-letter words and explain the need for Joyce’s unusual sexual candor. Woolsey seemed largely to be with him, but at one point said, “Still, there is that soliloquy in the last chapter. I don’t know about that.” Woolsey admitted that he found the book moving, and that it “bothered, stirred, and troubled” him. He spoke of the power he found in Joyce’s words: “Reading parts of that book almost drove me frantic.”

In his opinion, Judge Woolsey conceded that Ulysses contained erotic passages. “It must always be remembered that [Joyce’s] locale was Celtic and his season spring,” the judge wrote. But Woolsey saw the sex as part of Joyce’s “honest effort to show exactly how the minds of his characters operate.” He said Joyce’s purpose has “been so often misunderstood and misrepresented.” The book contained “no dirt for dirt’s sake,” but rather was part of an effort to paint a vivid picture of his character’s lives, lives lived in the lower middle class of Dublin in 1904.

Woolsey rejected the “most susceptible reader” test of the 1868 Hicklin case. He wrote instead books should be judged by how they affect “a person of average sex instincts.” He also bought Ernst’s argument that the prurient appeal of the book should be judged by its entirety, not by its dirtiest passages.

Joyce’s book, Judge Woolsey declared, was not obscene: “Ulysses may, therefore, be admitted into the United States.”

Within ten minutes of Woolsey’s decision on December 7, 1933, typesetters at Random House began working on the first American edition of Ulysses. In Paris, learning of the decision, Joyce said, “Thus one half of the English speaking world surrenders. The other half will follow.”

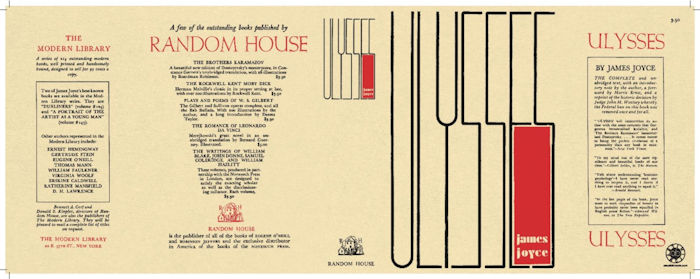

Cover for Random House's 1st Edition of James Joyce (1934)

Ernst suggested to Cerf that Judge Woolsey opinion be published as a sort of second foreword to the American edition of Ulysses. He thought the blessing of a federal judge might discourage overzealous prosecutors from using state obscenity laws to prosecute booksellers around the country. Joyce’s novel was published in New York on January 17, 1934. Time magazine put Joyce on its cover. In the accompanying story, Time said, “Last week a much-enduring traveler, world-famed but long an outcast, landed safe and sound on U. S. shores. His name was Ulysses.”

The government decided to appeal. The appeal would be heard by three judges of the Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit. One of the three judges assigned to the case was Learned Hand, often called the greatest American jurist to never sit on the Supreme Court. Joining him on the bench was his cousin, Augustus Hand, and Judge Martin Manton.

The government argued that Judge Woolsey had erred in ignoring Hicklin, and that under any fair reading of Ulysses, there were many passages that were obscene under the Hicklin test. U. S. Attorney Martin Conboy said, "The only exhibit iis the book itself." Judge Learned Hand asked, "Do you believe the court should read it?" Conboy replied, "No, I'll read a generous sampling of this product of the gutter." Conboy proceeded to spend hours reading allegedly obscene passages aloud, with special emphasis placed on Molly’s Soliloquy of the final episode. According to a New York World-Telegram report on the oral argument, Conboy stood “blushing, stammering, rocking nervously on his heels” as he read twenty-five offending passages. Meanwhile, the report said, the judges “looked solemn.”

Morris Ernst told the court that Joyce was an author of "majestic genius" and that "the real protagonist for this book is the human mind." He added, "The arena of action of Ulysses is not a Dublin brothel, but the human skull." Ernst argued, "The government was unfair in citing only excerpts from this book. It is necessary to consider it as a whole."

Learned Hand’s private memorandum to his fellow judges reveals his thinking. He noted that while some passages in the book “could excite lustful feelings,” that the passages cited by the government “are clearly necessary to the epic of the soul as Joyce conceived it.” Learned Hand called Ulysses “a very notable contribution to the literature” and the allegedly offensive parts “not sufficient to condemn” it.

Judge Augustus Hand

Augustus Hand authored the court’s opinion, which Learned Hand joined. Judge Manton wrote a dissenting opinion. Augustus Hand said the text in Joyce’s book was “sincere, truthful, relevant to the subject, and executed with real art.” He said the book had both "artistic merit and scientific insight." Rejecting the approach favored in Hicklin, Hand said Ulysses must be judged as a whole work, not just by its most offensive parts. Judge Woolsey’s decision was affirmed.

The United States decided not to file an appeal in the Supreme Court. The case was closed. Authors and publishers felt liberated.

James Joyce sent a copy of his book to Morris Ernst, who fought so hard and well to free Ulysses. Joyce wrote: “To Morris Ernst, valiant and victorious defender of this book in America, in respectful recognition, James Joyce, 5 October 1934.”