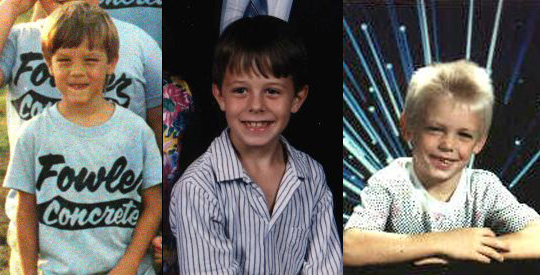

On a warm sunny May day three eight-year-old boys set off on a bike ride around their hometown of West Memphis, Arkansas. The next afternoon, their bruised and mutilated hog-tied naked bodies were pulled from a stream, setting off an all-out effort to find their murderers. Within a month, investigators were convinced they had found the killers, three out-of-the-mainstream teenagers who would become known as "The West Memphis Three." The convictions and court battles that followed provide a cautionary tale for police and prosecutors too sure of their instincts and too quick to rely on the questionable evidence that supports them.

The Investigation

About 8 P.M. on May 5, 1993, the West Memphis police department received a call from John Mark Byers reporting that his son, Christopher Byers, was missing. Byers and his wife Melissa told a patrol officer that Chris had last been seen about 5:30 working in the yard. Within the next ninety minutes, police responded to two more calls from worried parents. Dana Moore said she saw her son, Michael, riding off on bikes with two friends around six o'clock, but he never made it back for dinner. Pamela Hobbs said she hadn't seen her son, Stevie Branch, since he left for school. News of the three missing eight-year-old boys led to a search of a mosquito-infested four-acre woods near Interstate 40, where neighborhood children would sometimes play. The search, of the woods called Robin Hood Hills, turned up nothing--at least that night.

The next morning, Chief Inspector Gary Gitchell announced he would be heading up the search for the missing boys. In the early afternoon, Steve Jones, a juvenile officer, spotted a black tennis shoe floating in the water of a ditch in the Robin Hood Hills, near where the woods bordered the Blue Beacon car wash. Fifteen minutes later, Sergeant Mike Allen of the West Memphis Police Department pulled the naked body of a child to banks of the ditch, and yellow crime tape went up around the area. Within an hour, police recovered two more bodies of children. Both were naked, with wrists bound to ankles with shoelaces. The body of one of the boys, identified as that of Chris Byers, was found with its scrotum gone and its penis skinned. Gitchell walked to the edge of the woods, where a large crowd had gathered, to report the news of their discovery. Upon hearing the news, Terry Hobbs, stepfather of Stevie Branch, fell to the ground and wept.

Soon after the bodies were removed from Robin Hood Hills, rumors began circulating that the killings might have been the work of devil worshipers. Inspector Gitchell did nothing to squelch the rumors when he told reporters that his department was investigating the possibility that the murders were connected with "cult activity." The West Memphis Police Department assigned the case number 93-05-0 666 to the murder file.

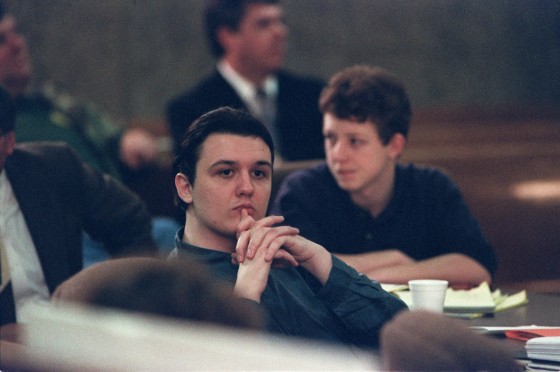

On May 7, Steve Jones, the juvenile officer who first discovered the bodies, interviewed a troubled local teenager, Damien Echols, who had been under the watchful eye of another juvenile officer, Jerry Driver, for some time. Echols was a seventeen-year-old dropout with a history of psychiatric problems, including major depression. Echols wrote dark poems, dressed mostly in black, wore long hair, had a tattoo on his upper arm, and was a self-described Wiccan. In the previous couple of years, Echols allegedly had threatened his former girlfriend and the boy she was then dating, as well as his father. During part of a several-month stay with his mother in Oregon in 1992, Echols had been admitted to a psychiatric ward and placed under suicide watch. Returning to Arkansas in the fall, Echols briefly entered a juvenile detention center before being transferred to a psychiatric hospital in Little Rock after biting and attempting to suck blood from the arm of another detainee. Following his release from the Little Rock hospital, Echols returned to West Memphis, where he met regularly with a social worker at a mental health center. The social worker reported in her notes that Echols told her he might become another "Charles Manson or Ted Bundy." Jerry Driver's knowledge of Echols convinced him that Damien might have a lot to do with the murders of Chris Byers, Michael Moore, and Stevie Branch--and he pushed his suspicions with members of the West Memphis Police Department.

Police questioned Echols about the Robin Hood Hills murders three separate times between May 7 and May 10, twice at the trailer park where he lived and once at the police station. Echols told investigators he "never heard of" the three boys and that the person who committed the murders was obviously "sick." He said he spent the evening of May 5 at home with his mother, talking on the phone with two girlfriends in Memphis. In his notes of the police station interview, Lt. James Sudbury reported that stated "the killer is probably someone local and that he won't run." He noted that Echols "likes to read books by..Steven [sic] King" and has "EVIL across his left knuckles." Echols willingly took a polygraph test. The administering officer concluded that Echols "recorded significant responses indicative of deception." In addition to Echols, investigators focused their attention on Jason Baldwin, a friend of Damien's who also had "EVIL" inked across his left knuckles. Like Echols, Baldwin denied any involvement in the killings, but detectives on the case increasingly thought otherwise.

Investigations might have stalled were it not for the work of a local waitress named Vicki Hutcheson. Hutcheson told police she suspected the killings were cult-related and that she was willing to "play detective." She believed that her connection with a seventeen-year-old neighbor, Jesse Misskelley, who sometimes babysat her children and mowed her yard, might provide an opportunity for her to explore the secret life of Damien Echols. Hutcheson told authorities that Misskelley, who had a IQ substantially below the normal range of intelligence, told her about Echols, his friend who "drank blood and stuff." With the blessing of the West Memphis Police Department, Hutcheson asked Misskelley to arrange an introduction to Damien, who she said she would like to go out with. Jesse agreed, and shortly thereafter brought Damien over to Hutcheson's house and made introductions.

What exactly happened between Hutcheson and Echols became clear only years later, but for the benefit of local law enforcement authorities, Vicki hatched quite a tale. She told investigators that on the night of May 19 she and Jesse were driven by Damien in a red Ford Escort (odd, given that Echols had no car and was never once known to have driven one) to an "esbat" (a gathering of witches) in a field outside of town where she encountered ten young people, each with faces and arms painted black, stripping off their clothes and "touching each other." She claimed those participating in the orgy used nicknames like Spider, Snake, and Lucifer. Offended by the naked activity, Hutcheson, according to her story, asked Damien to drive her back home, which he did, leaving Jesse at the orgy. In late May, Vicki Hutcheson and her eight-year-old son, Aaron, met with detectives. While Vicki shared her story about the esbat, Aaron told authorities the he and the three murdered boys often visited Robin Hood woods together, and that on one visit to the woods they saw five men sitting in a circle chanting and doing "what men and ladies do." On June 2, West Memphis police polygraphed Vicki Hutcheson (West Memphis seemed to have a lot of faith in polygraphs). Polygraph administrator Bill Durham reported that Hutcheson was telling the truth.

Arrests and a Confession

Convinced by the polygraph results that they had their murderer, the police pick up Jesse Miskelley for questioning about 9 A.M. the next day. They tell Jesse there was a $35,000 reward for information leading to convictions in the case and, if he helps them solve the case, his family will be eligible for the money. In a polygraph interview, Jesse initially denies participating in either Satanic rituals or the murders, but Detective Durham tells another officer Jesse is "lying his ass off." (Do polygraph examiners ever get it right in West Memphis?) After hours of harsh questioning by Gitchell and Ridge, Jesse begins to tell the officers what they want to hear: that he and Damien and Jason committed the murders. Later, Jesse would offer this account of his experience:

I kept telling [Inspector Gitchell and Detective Ridge] I didn't know who did it--I just knew of it--what my friend had told me. But they kept hollering at me...They kept saying they knew I had something to do with it, because other people had told 'em. After I told 'em what the three boys were wearing, Gary Gitchell told me, was any of them tied up? That's when I went along with him. I repeated what he told me. I said, yes they were tied up. He asked, "What was they tied up with?" I told 'em a rope. He got mad. He told me, "God damn it , Jesse, don't mess with me." He said, "No. They was tied up with shoestrings." I had to go through the story again until I got it right. They hollered at me until I got it right. So whatever he was telling me, I started telling him back. But I figured something was wrong, 'cause if I'd a killed 'em, I'd a known how I done it.

Eventually the inconsistencies that trouble officers (such as Jesse saying the murders occurred in the daytime when they actually occurred at night, or that they tied up the boys with rope when the actual murderer used shoelaces) are ironed out, and Jesse's story begins to match the known facts of the case. Some five hours after picking Jesse up, police taped Jesse's "confession." In the taped confession, Jesse states that while in Robin Hood Woods with Damien Echols and Jesse Baldwin, he watched Echols hit Chris Byers in the head "with his fist and bruised him all up real bad, and then Jason turned around and hit Steve Branch,...then the other one took off, Michael Moore took off running, so I chased him and grabbed him and hold him, until they got there and then I left." Jesse stated that when he returned to the scene minutes later, all three boys have their clothes off and are tied up: "Then they tied them up, tied their hands up, they started screwing them and stuff, cutting them and stuff, and I saw it and turned around and looked, and then I took off running, I went home, then they called me and asked me, how come I didn't stay, I told them, I just couldn't."

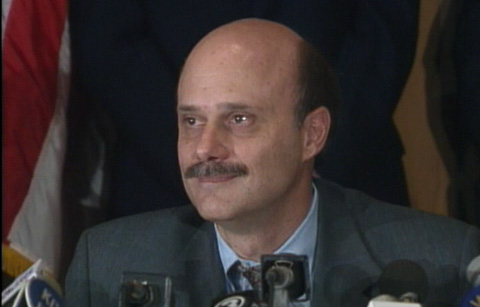

Within hours after securing Jesse's confession, Deputy prosecutor John Fogleman appeared before a municipal court judge for warrants that would allow searches of the homes of Misskelley, Baldwin, and Echols. By 10:30 P.M. on June 3, 1993, all three teenagers were rounded up and each charged with three counts of capital murder. At a press conference the next morning held to announce the arrests, Gary Gitchell is asked how confident he felt about his case, on a one-to-ten scale. Gitchell answers, "Eleven."

Working to strengthen their case to something beyond eleven on the ten-point scale, police decide to re-interview Vicki Hutcheson's eight-year-old son, Aaron. Aaron now tells a detective that he actually had been with the three boys in the woods and witnessed their murders. According to Aaron's account, he received a call the night before the murders from Jesse Misskelley inviting him to bring his three friends to the woods the next day where they would all "do something." Once there, Aaron said, Jesse, Jason, and Damien "slapped" his friends. "I ran and Jesse caught me. Then I got away, and he caught me again, and...he tied me up. I um, stayed there for about forty seconds and got untied." Asked by Gitchell how he was tied up, Aaron replied, "With a rope." Aaron said, "They couldn't hurt me, 'cause I kicked every one of them with a foot." Meanwhile, he said, his friends "got stabbed" and had their clothes pulled off. Then, he said, "They cut off the private spot." From a distance, Aaron told Gitchell, he watched as the three teens "raped Michael, Chris, and Steve." While Aaron's story would strike most people as wildly implausible, Gitchell was pleased: he now had a second eyewitness to the Robin Hills murders.

On August 4, 1993, Judge David Burnett presided at a pretrial hearing in Marion, Arkansas. Burnett ruled that Misskelley should be tried separately from Echols and Baldwin. Burnett also ruled that the state could introduce Jesse's confession, despite defense arguments that it was obtained under coercive circumstances. (The defense pointed to, among other things, the officers' "repeated refusals to believe his statements," showing Jesse a circle a diagram and telling him he had a choice to be in the circle "with the killers" or outside it "with the police," and playing a spooky audio tape of Aaron Hutcheson's voice in which he said, "Nobody knows what happened but me.") In another important pretrial ruling, Burnett concludes that all three defendants should be tried as adults rather than juveniles.

The Jesse Misskelley Trial

On January 18, 1994, jury selection in the Jesse Misskelley trial began in a one-story cinder block courthouse in Corning, Arkansas. In short order, a jury of seven women and five men was chosen, and John Fogleman rose to deliver the state's opening argument. Fogleman told jurors that while they might find errors and discrepancies in Jesse's confession, they were largely explained by Misskelley's efforts to minimize his own role in the killings. "I think you'll find that he lessened his own involvement," Fogleman said, but that "the proof is going to show that this defendant was an accomplice to Damien Echols and Jason Baldwin in the commission of these horrifying murders." Dan Stidham, representing Jesse, said the prosecution of his client was the result of "tremendous pressure" for arrests in this case and the "Damien Echols tunnel vision" of investigators that existed "from day one." He argued that Jesse's so-called confession came when interrogators "broke his will" and "scared him beyond all measure."

The first witnesses for the state were the mothers of each of the murdered boys. Each described the last time they saw their son on May 5 of the previous year. Despite the suspicions of defense attorney Stidham that the husband, John Mark Byers, of Melissa Byers might have been involved in the killings, he resisted the temptation to pursue that theory in cross-examination, fearing that to do so might only anger jurors who naturally sympathized with the parents. (Suspicion about John Mark Byers's possible role in the killings continued for years after the trial, fueled in large part by filmmakers of a documentary about the case. By 2012, however, almost no one believed Byers had anything to do with the murders. Instead, a new group of suspects emerged).

Fogleman took jurors on a disturbingly graphic journey. Detective Byrn Ridge testified about his search in the woods for the three missing boys, and the eventual discovery of the bodies. As he did so, jurors could gaze at the bicycles of the three eight-year-old boys, leaning against a wall at the front of the courtroom. Fogleman introduced into evidence more than thirty grisly photos of the boys, white, bound, and mutilated. Dr. Frank Peretti reported the findings of his autopsies as the jurors viewed more photos, these of bodies on the autopsy table.

Inspector Gary Gitchell took the stand to describe the circumstances surrounding Jesse's confession. Gitchell asserted that Jesse remained "very relaxed" during his long interrogation. Then Fogleman played the audiotape of Misskelley's thirty-four-minute long confession. The jury listened silently as the tape played. On cross-examination, Gitchell conceded that Jesse's initial story contained a number of errors, including that the killings took place near noon and that the boys had been tied up with brown rope. Gitchell dismissed the errors: "Jesse simply got confused. That's all."

Most courtroom observers expected the prosecution to call eight-year-old Aaron Hutcheson to the stand. After all, young Aaron was, according to the state, an eyewitness to the murders and his statements led to the arrests of Jesse, Damien, and Jason. Fogleman, however, knew that Aaron's account was implausible in numerous particulars, and feared what Stidham might do on cross-examination. He decided not to have Aaron testify, and instead called only his mother, Vicki Hutcheson. On the stand, Hutcheson told jurors she was motivated to "play detective" because "I loved those boys, and I wanted to see their killers caught." She described going to an esbat with Damien and Jesse, but--after a ruling by Judge Burnett that testimony about faces painted black and an orgy might be too prejudicial--offered few details other that she saw "twelve to fifteen" other young people at the gathering. On cross-examination, Hutcheson denied that the prospect of earning $35,000 in reward money had anything to do with her detective-playing.

With virtually no physical evidence connecting Jesse to the crime, Fogleman was left to call Lisa Sakevicius of the state crime lab, who testified that a green polyester fiber found on a cub scout cap of one of the boys was "microscopically similar" to fibers found on a shirt in Damien's house and that a red rayon fiber found near the bodies was also "microscopically similar" to the fiber of a red bathrobe found in Jesse's home. Sakevicius admitted that the results did not imply either the shirt or the bathrobe was worn by the murderers at the crime scene, but that it was possible the fibers were carried to the crime scene via a "secondary transfer." On cross-examination, the crime lab's finding appeared even less probative after Sakevicius conceded that many fibers are "microscopically similar" to each other and that the "discovery proved nothing." With that, and a few bits of evidence that allegedly supported the state's theory of a cult-motivated killing, such as the introduction of a book found in Damien's house titled Never on a Broomstick, the state rested its case.

The critical decision faced by defense attorney Dan Stidham was whether to allow Jesse to testify. Jesse's low IQ presented a problem. Stidham feared that Jesse could be made to say almost anything in a grueling cross-examination by Fogleman. Instead, Stidham decided upon a theory of attempting to raise reasonable doubts about the prosecution's story.

Stidham considered one of his most important witness to be Warren Holmes, a detective and polygraph examiner associated with several well-known cases, including Watergate and the assassinations of John F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King. Holmes was prepared to testify that his review of the polygraph results indicated that Jessie truthfully answered all questions except one, a question relating to his prior drug use. Officer Durham, he believed, lied to Jesse about his polygraph results in an effort to scare Jesse into making a confession. Judge Burnett, however, thwarted Stidham's plans when he ruled that testimony about the results of a polygraph test, whether the results suggested innocence or guilt, was never admissible under Arkansas law. Burnett allowed, for purposes of a possible appeal, Holmes to testify outside of the presence of the jury about factors contributing to false confessions. Holmes said warning signs including having the confessing subject tell you nothing "you don't already know," having what they do say not fit with known facts about the case, and having the story of the crime not told "in narrative form." In the case of Jesse's confession, Holmes said, all three of these warning signs appeared. Holmes said that telling someone they failed a polygraph test can lead to a false confession because they tend to view the test as "a last hope," and when they are told they are lying, "their will is beaten to a pulp, and then they just give up." Holmes also criticized the failure of authorities to take Jesse to the crime scene where factual disputes about the truth of his statement might have been resolved. After finishing his proffered testimony, Burnett allowed Holmes to testify in front of the jury only concerning a few matters, such as the fact that Jesse "certainly knows the differences between shoelaces and a rope."

Even more critical to the defense case, in Stidham's opinion, was the testimony of social psychologist Dr. Richard Ofshe. Stidham hoped that Ofshe could explain to the jury why coercion during the police interrogation made Jesse's confession involuntary. Barely had Stidham began asking questions, however, when the prosecution objected, arguing that the matter was one for the jury to decide, not for an expert to opine about. In an in-camera hearing, Judge Burnett made clear where he stood on the matter: "I'm not prepared to allow him to testify that in his opinion [the confession] is coerced and therefore invalid. I mean, what the hell do we need a jury for?" Stidham insisted the matter of coercion was distinct for the question of validity. In the end, Judge Burnett allowed Ofshe to testify that Misskelley had given police a "false statement" when he could "no longer stand the strain of the interrogation." He also told jurors that people "who have low self-esteem" or are "mentally handicapped"--two apt descriptions of Jesse--are especially "at risk to responding to coercive and overly persuasive tactics." Ofshe was not allowed to tell jurors, however, that in his opinion the tactics used by the West Memphis Police Department overrode Jesse's will and resulted in a false confession. On cross-examination, prosecutor Brent Davis quizzed Ofshe about the meaning of coercion, forcing him to admit that police had not physically abused Jesse or treated him a degrading way, and that the "coercion" in this case consisted mainly of a few suggestive questions. Davis's questions on the nature of coercion in Jesse's interrogation opened the door for Stidham to ask question on re-direct examination that the prosecution had hoped would not be asked. Ofshe rattled off examples of suggestive questions in the initial stages of the interview that he said shaped Jesse's taped confession. On re-cross, Davis asked one final, ill-advised question. Couldn't a person always say "I don't know anything about it," he wondered? Ofshe answered, "They can. And sometimes they get to the point at which they can no longer do that and so they simply give up."

In the first closing argument for the state, Fogleman told jurors, "There is absolutely not one iota of evidence that [Ridge and Gitchell] have told anything other than the truth in this courtroom...There's no evidence of any form of coercion. What is the defense? Are they saying that the defendant was brainwashed? Is that what they're saying?" Defense attorney Stidham, in his closing, suggested, "Killing one human being by another is only exceeded by the state killing an innocent man." Finally, prosecutor Davis, in his closing argument, said that the defense's "so-called experts" had "tried through smoke and mirrors to make it sound like a person that confesses to such a heinous crime, and admits their involvement, and gives you specific details of the involvement" was forced to do so. He asked jurors do "apply your common sense" and "do what's right."

Jesse held his head low the next day when the jury returned to the courtroom the next day to announce its verdict. Guilty of first-degree on all three counts. In her account of the West Memphis case, Devil's Knot, Mara Leveritt reports Jesse's reaction (recalled years later) as he heard the verdict announced: "When that verdict came in--eeee-yewww!--I just knew my life was over right then." In the penalty phase of the trial, the jury decided to sentence Jesse to life in prison without opportunity for parole. Asked by Judge Burnett if he had anything to say before sentence was imposed, Jesse answered, "No."

The Echols/Baldwin Trial

Two weeks after the verdict in the Misskelley trial, jury selection began in a Jonesboro, Arkansas courtroom for the trial of Damien Echols and Jason Baldwin. Only the day before the trial opened, Dan Stidham announced, "Mr. Misskelley made a decision last night that he is not going to testify against his co-defendants." Without Jesse's testimony, the state was left with a thin, circumstantial case--but it did have a helpful ruling from Judge Burnett denying a motion filed by Baldwin's attorneys asking that he be tried separately. Prosecutors could hope that the evidence tying Echols to witchcraft, as well as some damaging statements by Damien, might lead a jury to a conclusion of "guilt by association" in Baldwin's case.

John Fogleman spoke first to the jury, telling them that the state would prove "through scientific evidence" and "the statements of these own defendants" that "they caused the deaths of Michael Moore, Stevie Branch and Chris Byers." Representing Jason Baldwin, Paul Ford argued that Jason Baldwin, only sixteen when he was arrested, "is not a troublemaker." He took care "of his two younger brothers, getting them to bed. And in the morning, when Mom is still asleep because she's been up late, and it's Jason who has the obligation of getting himself up, getting his brothers up, getting everybody dressed and fed and catch the bus and go to school. That's the kind of person Jason Baldwin is." Ford argued his client was in court only because police had disregarded statements and the physical evidence. "You'll see that this evidence that they have...has been twisted and manipulated and distorted in order to make the pieces of the puzzle they want to build to fit together. And you'll see that from their own witnesses. Lastly, you will see from their own witnesses, evidence that will show that Jason Baldwin is innocent." Scott Davidson, attorney for Damien Echols, used his opening statement to address one of his biggest concerns, that the jury might find his client guilty because of some of the strange statements and actions in his past. "He's not the all-American boy," Davidson observed. "He's kind of weird. He's not the same as maybe you and I might be...But I think you'll also see that there's simply no evidence that he murdered these three kids."

The Prosecution

The prosecution began making its case against Echols and Baldwin in much the same way as it did against Misskelley in his trial, with parents describing the last time they saw their sons and detectives describing how they found the bodies and what they found at the crime scene. When Detective Bryn Ridge, in response to a question on cross-examination about a delay of two months in retrieving a piece of crime scene evidence, said, "I didn't take that stick into evidence until the statement of Jesse Misskelley, in which he said--", Val Price immediately asked for a mistrial. Price insisted that "blurting out the fact that Jesse Misskelley gave a confession" was extremely prejudicial and unwarranted by his question, but Judge Burnett was unmoved. "There isn't a soul up on that jury or in this courtroom that doesn't know Mr. Misskelley gave a statement," the judge said, explaining his decision to deny the motion.

In later testimony, Ridge reported that during Damien's long interrogation at the police station he had claimed all persons hold "demonic forces inside them," made observations about the mystical significance of water, and noted that three--the number of boys killed, of course--was "a sacred number in the Wicca religion." Moreover, Ridge testified, Damien acknowledged reading books by Stephen King, an author famous for his horror novels--a fact Ridge thought was "strange." Further developing its theme of a cult-related motive, Fogleman called Damien's former girlfriend, Deanna Holcomb, to tell jurors Damien "wore all black" and carried knives, sometimes in his trench coat pocket. An officer who conducted a search of Damien's home testified that the search turned up eleven black T-shirts, the book Never on a Broomstick, and the skull of a dog. The prosecutor also asked Judge Burnett to take "judicial notice that there was a full moon on May 5, according to the almanac"--a request the judge found "appropriate." Delving into matters of the occult took center stage with the calling of Dr. Dale Griffis, a "cult expert" from Ohio. Griffis testified that the number three was "one of the most powerful numbers in the practice of satanic belief." When asked on cross-examination whether the number three might also have special significance in the Christian belief system (consider, for example, the notion of the Trinity), Griffis said, "I cannot make that statement." Griffis said that the murderers of the three boys "were using the trappings of occultism during this event," pointing to "the time of the moon phase" and "the removal of blood" as examples of "trappings." Asked what significance the sucking of blood might have, Griffis explained, "Blood is the life force. And usually they will take--they prefer to have a child that is young, very young, and the younger, the more innocent, the better the life force."

With medical examiner Dr. Frank Peretti on the stand, Brent Davis handed his witness a knife discovered in a lake behind Damien's house. Peretti agreed that wounds found on the body of Chris Byers were "consistent with the serrated portion of that knife." On cross-examination, Peretti conceded that the Byers' wounds were equally consistent with another serrated knife, in particular one belonging to John Mark Byers, Chris's stepfather. The knife wounds to Chris's genital area, Peretti said, were "antemortem." In other words, Chris's scrotum was cut off, and his penis skinned, while he was still alive. Peretti also told jurors that the autopsies revealed both Stevie Branch and Michael Moore received massive blows to their heads, and that Michael's lungs were filled with water, indicating that, "when he was in the water, he was breathing." Defense lawyers got Peretti to acknowledge on cross-examination that many of the descriptions of the murder offered by Jesse in his confession were not confirmed by his medical findings--none of the boys were strangled, raped, or tied with any sort of rope.

The crowd in the courtroom gasped in shock when prosecution witness Michael Carson, a sixteen-year-old who shared jail time with Baldwin, testified that Jason admitted to him that he "dismembered the kids" and "sucked the blood from the penis and scrotum and put the balls in his mouth." Carson told jurors he came forward with his story, months after his alleged conversation with Jason, because he saw on television how "brokenhearted" the parents of the missing boys were and because "I have got a soft heart. I couldn't take it." Carson's explosive testimony, and the thin reed of a bathrobe fiber from Jason's home that was said to be "microscopically similar" to a fiber found near the bodies, represented the entire prosecution case against Jason Baldwin. (The state's case against Jason was sufficiently weak that they had earlier approached his attorneys with a proposal to ask only for a sentence of forty years, with parole possible in fifteen, in return for his testifying against Damien. Jason emphatically rejected the proposal.)

Detective Mike Allen pointed to spot on a map of the area around the trailer park where Baldwin and Echols lived to indicate where in a lake divers found a serrated knife that the state now implied was the likely weapon of mutilation wielded by Damien on May 5, 1993. On cross-examination, Allen was asked whether he in fact was claiming that the knife was the murder weapon. "No, sir," Allen answered, "I am not telling the jury that." Recalled to the stand for questioning about the knife, Detective Ridge acknowledged that the idea to hunt in the lake behind the Echols trailer came not from any law enforcement officer, but from the prosecutor, John Fogleman. Besides the disputed knife, the only physical evidence allegedly connecting Echols with the crime was "a trace of blue wax" found on the shirt of one of the murdered boys and a polyester fiber recovered from a cub scout cap that, according to Lisa Sakevicius of the state crime lab, was "microscopically similar" to fibers found on a shirt in the Echols home.

The prosecution wrapped up its case with the testimony of two girls who claimed to have overheard Damien confess to the murders while attending a softball game. Jodee Medford, a junior high school student, said she was watching the game when she heard Echols, at a distance of about twenty-five feet, "say that he killed the three little boys and before he turned himself in, that he was gonna kill two more and he already had one of 'em picked out." On cross-examination, Medford admitted that though she told her mother about the overheard comment, neither she nor her mother bothered to report the matter to police. Medford's story generally matched that of her twelve-year-old friend, Christy Van Vickle, who attended the girl's softball game with her that evening in May 1993.

The Defense

After opening its case with testimony from Pam Echols, who told jurors her son spent the night of the murders at home with her, and in phone conversation with two girlfriends, the defense called Damien to the stand. Val Price asked Damien about his family history and his interests, which Damien said included skateboarding, movies, talking on the phone, and reading. He then asked Damien about his focus on the Wicca religion, which Damien explained was "basically a close involvement with nature." "I'm not a satanist," Damien insisted. "I don't believe in human sacrifices or anything like that." Price asked Damien to read excerpts from his personal journal, which included favorite quotes such as "Life is but a walking shadow. It is a tale told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing," from Shakespeare's "Macbeth." Asked why he kept a dog skull in his bedroom, Damien replied, "I just thought it was kind of cool." Asked why he had the word "evil" tattooed across his knuckles, Damien had a similar answer: "I just kinda thought it was cool, so I did that." Questioned about why he always wore black, Damien responded, "I was told that I look good in black. And I'm real self-conscious, uh, the way I dress." And so it went. The defense sought to present Damien as a teenager who might be different from most in West Memphis, but not as someone anyone should fear. Echols denied having anything to do with the deaths of the three boys, testifying, "I'd never even heard of them before 'til I saw it on the news." Asked how he felt about being charged with the murders, the defendant said, "Sometimes angry. Sometimes sad. Sometimes scared."

The defense presented evidence raising questions about the quality of the police investigation. Gary Gitchell admitted that although West Memphis owned both a video camera and audio recorders, they hadn't bother to tape any of their several interviews with Damien Echols. Gitchell also admitted that blood samples left on the wall of a Bojangles restaurant on the evening of the murder were "as the term is, lost." John Mark Byers, the stepfather of victim Chris Byers, was called to testify about a knife he had given an HBO film crew working on a documentary about the case and that later was turned over to police. Byers testified that the blood found on the knife was his, coming from a cut, despite the fact that he had repeatedly told authorities he had "no idea" how human blood ended up on his knife. A plan by the defense to call Christopher Morgan, a teenager who once confessed (and later recanted) to California police that he might have "blacked out" and killed the three boys in West Memphis, was thwarted when Morgan's attorney announced in a hearing before Judge Burnett (from which the press was excluded) that his client, if forced to testify, would invoke his Fifth Amendment rights against self-incrimination. Of course, that's exactly what attorneys for Echols and Baldwin wanted to have happen. Prosecutors argued strenuously that Morgan's taking the Fifth, which Morgan's attorney insisted related to pending federal drug charges against his client that might be vaguely related to the murders, would mislead the jury, who would quite naturally conclude that Morgan was hiding his involvement in the actual murders of the three young boys. Burnett ruled that he would not force Morgan to testify and said that anyone who mentioned his ruling to the press "or anyone else...will be held in contempt, and I mean it."

With what defense attorneys viewed as their best witness now off the hook, they called as their final witness Robert Hicks, a police training officer with expertise about satanic crime. Hicks testified that he knew of no connection between sexual mutilation and the occult. He also told jurors that "we do have empirical evidence" that listening to Metallica music does not "lead people to commit crimes." He described the phrase "trappings of the occult," used by prosecution expert Dale Griffis, as "absolutely meaningless in considering any kind of violent crime."

That was it. The defense rested. Jason Baldwin never testified, his attorney hoping that his client's low profile and the scant evidence against him would save his client. "We wanted to just disappear on the radar screen and let Damien be the whole focus," Paul Ford said later. "We thought, if we didn't stir the pot, and they didn't stir the pot, what were they going to convict him on?"

On March 17, the jury listened to closing arguments. John Fogleman argued that while most people might not believe "this satanic stuff," what "matters is what these defendants believe." Religion, he said, "is a motivating force. It gives people who want to do evil, want to commit murders, a reason to do what they're doing." Fogleman told jurors that when "you see inside [Damien], and you look inside there, there's not a soul there." Val Price, the lead defense attorney for Damien, reminded jurors that the law required them to find his client guilty beyond a reasonable doubt--and, after listening to the evidence, they should have plenty of doubts. He pointed to the blood found on the knife owned by John Mark Byers, the bloody man who entered a local Bojangles restaurant about the time of the murders, and the almost not existent physical evidence connecting Damien with the murders. He argued that having "weird things in your room...doesn't mean you're guilty of murder." Paul Ford delivered the closing argument for Jason Baldwin, arguing that the prosecution hoped jurors would find his client "guilty by association." "Take the blindfolds off," he told jurors, and look at this case "they way it really is--and send Jason Baldwin home." The final argument belonged to prosecutor Brent Davis. Summing up, Davis said, "We have presented a circumstantial case with circumstantial evidence, and it's good enough for conviction." He told jurors "you can feel good" about convicting both defendants.

The Verdict and Sentence

The following afternoon jurors returned to the courtroom with their verdict. Judge Burnett read the from the verdict forms the jury's findings. Both defendants were guilty of capital murder in the deaths of all three boys. Family members of the murdered boys cheered and hugged. Jason seemed to cry, while Damien showed little emotion. Terry Hobbs, Stevie Branch's stepfather, told reporters he hoped both defendants would be executed: "Those guys took a life, let them lose a life." He only wished he could have "ten minutes alone" with Baldwin and Echols "to do to them what they did to the boys."

In a second punishment phase of the trial, the jury listened to evidence relating to aggravating and mitigating circumstances for each of the two defendants. After listening to several hours of testimony, much of it concerning Damien's mental state and statements he had made to a therapist, the jury retired to the jury room and began scribbling out "pros" and "cons" for Jason and for Damien. Jason earned several "pros": "stuck to story," "exhibited remorse," and "in school." He got "cons" for being "Damien's best friend," his "jailhouse confession," "low self esteem," and "frequented crime scene." Damien got "pros" only for being "intelligent" and "manic depressive," for having a "loyal family," and for sticking to his story. His long list of negatives, however, included "Satanic follower," "manipulative," "dishonest," "weird," "something to gain," "blew kisses to parents," "inappropriate thought patterns," and "eat father alive." The jurors decided to sentence Jason to life in prison without opportunity for parole. Damien, the jurors concluded, should die by lethal injection. After Judge Burnett sentenced Echols to die on May 5, the defendants were led out of the Jonesboro courtroom. Jason Baldwin was transported to the penitentiary at Pine Bluff, while Damien Echols began life on death row in the state's maximum security prison near Varner, Arkansas.

Efforts to Free the West Memphis Three

Attorneys for Misskelley, Baldwin, and Echols each filed appeals to the Arkansas Supreme Court. The Supreme Court issued a unanimous opinion on February 19, 1996, upholding Jesse's conviction. Ten months later, in a ninety-three page opinion, the seven justices unanimously upheld the convictions of Baldwin and Echols.

But that was far from the end of the controversy surrounding the convictions of what people began calling "The West Memphis Three." In 1996, HBO aired a documentary called Paradise Lost: The Child Murders at Robin Hood Hills. The film, with a sound track by Metallica, depicted West Memphis as a hellhole with residents blinded by fantasies of a satanic cults, and jurors unable to sort facts out rationally. The film spawned a movement, and soon a website dedicated to gaining the release of the West Memphis Three, wm3.org, was established. The film also led to a marriage. Lorri Davis, a landscape architect, began communicating with Damien Echols after seeing the film in New York City. In December 1999, Davis and Echols married in a Buddhist ceremony performed at the maximum security prison.

Concerns that The West Memphis Three might have been wrongfully convicted continued to grow following the release, in March 2000, of the film Paradise Lost 2: Revelations, which suggested the real killer of the three boys was John Mark Byers. The Paradise Lost sequel was followed two years later with an exhaustive analysis of the case by Mara Leveritt in her book Devil's Knot: The True Story of the West Memphis Three. Like the filmmakers, Leveritt argued that a miscarriage of justice occurred in the 1994 trials. In 2003, Vicki Hutcheson, who had testified about attending an esbat with Jesse and Echols, told a reporter for the Arkansas Police that everything she had told the police a decade earlier was a lie. She reported that she felt compelled to cooperate with police out of a fear that if she didn't, the police would take her son away.

Another bombshell fell in 2007 after DNA found at the crime scene was retested, and none is found to match the DNA of Echols, Baldwin, or Misskelley. A hair found in a knot used to tie up one of the victims is, however, found to be "not inconsistent with" Terry Hobbs, stepfather to Stevie Branch. On the basis of the new evidence, John Mark Byers told reporters that he now believed the three young men convicted were innocent. The new DNA evidence failed to convince Judge Burnett that a new trial for any of the West Memphis Three was justified, but attorneys for all three appealed Burnett's decision to the Arkansas Supreme Court.

Finally, on November 4, 2010, the defendants received the first good news in their cases that they have heard from any court anywhere. The Arkansas Supreme Court announced an opinion ordering the trial court to reconsider whether newly discovered DNA evidence, or new evidence of juror misconduct in the original trials, justified ordering a new trial or exoneration of the three defendants. Prosecutors, aghast at the prospect of retrying the case, scrambled.

In his book published in 2012, Life After Death, Damien Echols described his feelings in August 2012, as he waited for word as to whether Jason Baldwin would agree to enter an Alford plea (plead guilty and yet maintain innocence) in a deal with the state that would result in the release of the West Memphis Three:

"The prosecutor wanted all three of us--Jesse, Jason, and me--to take the deal or there would be no deal. Over the years Jason had grown to love prison. His circumstances were not the same as mine. He had a job, he had befriended the guards, and was actually looking forward to next year in prison school. Jason has also said previously that he wasn't willing to concede anything to the prosecutors. I understood that with all my heart, and I knew he still believed he would be exonerated one day and walk freely through the prison gates. But...the state was too corrupt to ever let that happen....I was trapped in a nightmare, chained to someone I couldn't communicate with.

I paced back and forth in my prison cell, two steps to the door and then two steps back. Over and over and over I paced, at all hours of the day and night. I couldn't sleep, couldn't eat, couldn't read, couldn't even sit still. I wept. I cursed. I raged. To see home so close and yet still beyond my reach was pain beyond articulation."

Jason finally agreed to the deal. He said later, "I didn't take the deal for me. I took it for Damien." At a hearing on August 19, 2011, Judge David Laser, having replaced Judge Burnett on the case, called what happened a "tragedy on all sides." And then Jesse Misskelley, Jason Baldwin, and Damien Echols walked free into the Arkansas sunshine.

What Really Happened in Robin Hood Woods

A documentary film about the 1993 killings, West of Memphis (a film paid for and produced by well-known director Peter Jackson), released in 2012 strongly suggested that Terry Hobbs, stepfather of victim Stevie Branch, participated in the murders of the three boys. The filmmakers noted that the most significant piece of DNA evidence found at the crime scene, DNA in a hair found in one of the shoelaces used to tie up the boys, matched the DNA of Hobbs (as well as 1.5% of the population), and that a second hair found on a tree stump near where the bodies were found matched that of David Jacoby, a friend of Hobbs. The filmmakers also noted that Hobbs had a long history of abuse, including an admitted assault on his wife and accusations of child beating and assaults on neighbors. To this mix of circumstantial evidence, the filmmakers included an interview with an aunt of Stevie Branch, Jo Lynn McAughey, who alleged that she saw Hobbs doing laundry the night of the murders, presumably to clean the mud off of his clothes after killing the boys in the woods. The filmmakers also reported that a prized pocket knife owned by Stevie, one he almost always carried with him, was later found among Terry Hobbs's possessions. Finally, and perhaps most damningly, the filmmakers produced three young men who claimed to have been told by a nephew of Terry Hobbs that the fact that Terry killed the three boys was a closely guarded "family secret."

In 2013, what seems likely to be close to the true story of the West Memphis murders finally emerged in separate affidavits signed by Billy Wayne Stewart and Bennie Guy. The level of detail and overall plausibility of the stories told in the affidavits make them seem highly credible, even if they do come from an admitted drug dealer and a convicted felon. On May 5, 1993, according to both Stewart and Guy, Terry Hobbs, David Jacoby, and two teenagers from a local trailer park, L. G. Hollingsworth and Buddy Lucas, showed up at his West Memphis home looking to buy some pot, which Stewart provided. While Stewart sold the two boys the pot, he noticed Hobbs and Jacoby kissing in a pick-up truck across the street. (According to Stewart, Hobbs was a bisexual with a preference for sex with young boys. Hobbs, he stated, had invited his own ten-year-old son to pool parties--invitations which Stewart insisted his son decline.)

What happened after Stewart sold the pot on May 5 was told to Stewart by Buddy Lucas in April 1995. Getting back in the pick-up, Hobbs, Jacoby, and the two boys drove around town, smoking pot and drinking whiskey, before heading down a dirt road by the Blue Beacon Wood. At that point, according to Lucas's account, Terry Hobbs asked the two teenagers to get out and "wrestle" while he and Jacoby watched. While Lucas does not specifically say the wrestling soon turned into sexual activity involving him, L. G. Hollingworth and the two men, Stewart had no doubt that is what happened, asserting in his affidavit that the lowered head and shame evident on the boy's face as he told the story made it clear there was "more going on between the boys and the men than what Buddy had just told me." It was during this likely sexual activity that Chis Byers, Michael Moore, and Stevie Branch appeared on their bikes, at the wrong place at the wrong time. Stewart says Lucas told him that Terry Hobbs screamed, "Get them little fuckers!" While Jacoby beat one of the kids, Hobbs ordered Buddy and L. G. to pull off his pants. According to the Stewart affidavit, "Mr. Hobbs walked over to the boy that Mr. Jacoby had been beating and repeatedly bit the boy's penis and scrotum," then "cut the boy's genitals." Terry Hobbs then announced the other two boys had to be killed because of what they had seen, and Hobbs and Jacoby proceeded to do just that. The boys' clothes and bodies were gathered and dragged to the water, and their bikes thrown into the bayou.

Bennie Guy's affidavit tells a similar story. Guy stated that while Buddy (who Guy described as "pretty bad slow") was staying in his home in 1994 he confessed his involvement in the killings. Guy said in his affidavit that L. G. Hollingsworth also confessed to participating in the murders while both he and L. G. were incarcerated in the Crittenden County Jail in 1995. Hollingsworth's confession added a few new details to that of Buddy's. Terry Hobbs, in Hollingsworth's account, became enraged after one of the boys began kicking him. Hobbs hit the boy in the head and shouted, "I am going to teach your fucking ass." Hollingsworth said that he, Buddy, and the two older men all participated in beating the three eight-year-old boys, and he confirmed Buddy's assertion that Hobbs ordered the two teens to take off the pants of the boys, before cutting the genitals of one of them with his knife. In addition to Guy and Stewart, count Pam Hicks, the former wife of Terry Hobbs and the mother of Stevie Branch, among those convinced Hobbs murdered her son. Hicks launched a legal effort in March of 2013 to obtain additional evidence that might link Hobbs to the crime.

Shockingly, according to Billy Stewart, when he tried to call West Memphis Police investigator Bill Sanders in 1995 to tell him the story he had heard from Buddy Lucas, Sanders never even bothered to return his phone calls. If this allegation is true--and it certainly rings so--readers can debate whether that decision, which doomed three innocent young men to sixteen more years in Arkansas prisons, or the murders in the Blue Beacon Wood, was the greater tragedy.

The West Memphis Three: Life After Prison

Damien Echols now lives in Salem, Massachusetts with his wife Lorri. Although it won't win him back twenty lost years and means "constantly ripping wounds back open," Damien continues to fight for his exoneration. In his new life, he has gone paragliding in New Zealand with Peter Jackson, known to many as the director of the Lord of the Rings movies, and become good friends with actor Johnny Depp. In a 2013 article in Rolling Stone magazine, Depp said of Echols, "You expect a time bomb, but Damien's so kind and loving and open to the possibilities and the world. He's the strongest human being I've ever met."

Jesse Misskelley is the one member of the West Memphis Three who has maintained a low profile since his release. He lives and works in West Memphis, and is reluctant to talk to the media.

Jason Baldwin, who taught classes to other inmates in prison, helped produce a feature film about the West Memphis case called "Devil's Knot," starring Reese Witherspoon (as Pam Hicks, the mother of victim Stevie Branch) and Colin Firth (as defense investigator Ron Lax). He says he'd like to work on behalf of the wrongly accused and hopes to attend law school. Life is getting better, Baldwin says. "We all lived through this horrible time in our own way and got through it differently, so now I guess all have a different way of healing."