|

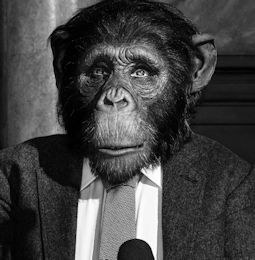

Police sketch from 1954 of a possible suspect in the Sheppard murder.

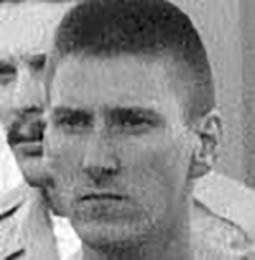

Richard Eberling in prison

Eberling Didn't Do It: Ten Reasons to Believe He's Innocent

1. As much reason as their might be to suspect Eberling, there's even more reason to believe Sam murdered Marilyn. See: DID SAM DO IT?

2. Despite the conclusion of an expert for the Sheppard family who found only 1 of 42 people having DNA profiles matching blood in Marilyn's bedroom, and that Eberling--but not Sam Sheppard--was among the small group with a consistent DNA profile, the blood evidence points in the other direction. Eberling had type A blood. No type A blood was found in the Sheppard bedroom.

3. Despite Eberling's confessions and near-confessions, there is reason to doubt their validity. Eberling was facing life in prison anyway, so what did it matter to him if people suspected him of killing Marilyn? He might have enjoyed all the attention from the media and litigators that came from his Sheppard connection and his statements about the case.

4. Eberling offered several demonstrably false accounts of the Sheppard murder. He spun a wild story about a double murder committed by Spencer and Esther Houk, for example. In short, he's a known liar.

5. Eberling passed a lie detector test in 1959. His answer that he did not kill Marilyn showed no signs of deception, according to the evaluating expert at the time.

6. In 2004, a dying man who worked for Dick's Window Cleaning service said it was he--and not Eberling, as Eberling had said--who washed windows at the Sheppard home two days before the murder, on July 2, 1954.

7. There was no sign of forced entry into the Sheppard home.

8. Sam Sheppard, even as he sat near Eberling as Eberling gave testimony in Sam's 1966 retrial, never suggested that Eberling was the "bushy-haired man" that he fought with on July 4, 1954. In fact, Sheppard, working with attorney F. Lee Bailey, helped develop the Houks-as-murderers theory.

9. Eberling had no clear motive for killing Marilyn. Nothing belonging to the Sheppards was found in Eberling's house except Marilyn's cocktail ring--and that was stolen three years after her murder from a box at the home of another member of the Sheppard family.

10. Eberling's fingerprints did not turn up in a search of the Sheppard home. Sam's, of course, did.

Dates

April 29, 1996: Kathie Collins, the former nurse for Durkin, says that Eberling revealed to her that he killed Marilyn Sheppard. Eberling later denies ever making such a statement.

March 4, 1998: Terry Gilbert, lawyer for the Sheppard family, announces that DNA tests performed by Dr. Mohammed Tahir of the Indianapolis -Marion County Forensic Services Agency, exclude Sam Sheppard as the source of blood found at the murder scene and show that the blood of Eberling is consistent with the blood type found at the scene.

July 25, 1998: Richard Eberling dies while serving a life sentence for murder.

August 19, 1998: Robert Lee Parks, an inmate at the Oriental Correctional Institution, says that shortly before he died, Eberling confessed to Marilyn Sheppard's murder.

In Eberling's Own Words

(Source: Cooper and Sheppard, A Mockery of Justice (1995), pp. 314-316)

Question: What would you like to be remembered for?

Eberling: Actually, nothing. I'd like to dry up and go away. I'd like to be remembered for good things. I helped people out. I've been very considerate of people.

--------------------------------------------------------------------

Eberling: I'm a pretty self-reliant person.

Question: Meaning?

Eberling: That means I can cope on my own. Even in here [prison].

Question: Is that part of the problem?

Eberling: I cope with that also. I think I can control myself

Question: Well, yes, but can you control events around you?

Eberling: Probably. Like I know I'm gonna be out of here. I'll kick and scream until I get out. The only thing I know [is] it takes time.

Question: What do you do when you get mad?

Eberling: I don't normally get mad. In here, I've learned more patience than ever. I ride over it.

Question: Where does the anger go?

Eberling: It's just held within. It wastes itself out. It just works itself out.

------------------------------------------------------------------------

Question: What did you think of Marilyn Sheppard?

Eberling: Marilyn had trouble up till the day she died. She was a lovely lady. A very fine lady. She was very respectable. I think she was lonesome because she let a lot of family dirt out to me.

Question: Would you have dated Marilyn Sheppard if you had met her before [Dr.] Sam?

Eberling: I probably would have dated her once or twice. [Shaking his head.] Probably not. I was an orphan, she was a golden girl. A golden girl looks for position, and me, being a nobody ... I wasn't good enough.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------

Eberling: (Referring to a claimed rape, unrelated to the Sheppard case): If she paraded for him like she paraded for me, she asked for it. She was all dolled up in the middle of the afternoon for the window washer. Put on all that feminine charm.

Question: Why do you say, "She asked for it"?

Eberling: Beguiling ways. Built the heat up. A man doesn't walk into a woman's house and rape her unless something provoked him. I place the blame on her. She decorated that place like a cheap whorehouse.... The way the house was decorated it set a provocative mood.

Question: You're saying that a man...

Eberling: I know that does not call for raping a woman. None of that calls for raping a woman.... Rape-usually it's an intentional thing. I can't understand how a man can enter a woman's home and rape her. Unless the husband went someplace…

Question: Do you know about an attempted rape of Marilyn Sheppard?

Eberling: I don't believe there was an attempt to rape. Rape was not as common as today. For a neighbor to go in that would not have made sense. That would have closed off all social avenues.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------

Question: A prisoner wrote and said that he met a man who worked for a hospital in a bar outside Cleveland, this was in the seventies, and the man said he had murdered Mrs. Sheppard.

Eberling: If Sam had hired someone to kill Marilyn, it would be a different story. I don't know why anyone would say that. Some things you tell and some things you don't tell. Why would anyone sit in a bar and claim that?

------------------------------------------------------------------------

Question: A detective named Howard Winter wrote an article in the fifties, and he thought the murderer was someone who had been watching Mrs. Sheppard, maybe knew her casually, and was emotionally disturbed or unstable in some way, confused about his sexuality.

Eberling: Nobody in the neighborhood fits that.

------------------------------------------------------------------------

Question: What did you mean you said Esther Houk's mind was on a merry-go-round?

Eberling: I think that's what happened. The more she thought the more she thought. After the deed was done, Spen thought he could cover it up.

Question: That merry-go-round, is that like what happens to you?

Eberling: Yep. My mind goes a mile a minute.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------

Question: What would happen if you were in touch with your feelings?

Eberling: I think I have feelings. I have feelings. Like this place [prison] I consider my home. The guards I consider babysitters.

Question: Is that a feeling?

Eberling: That's a feeling. So I don't hate it; I just adjusted to it.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Eberling: I've never thought about my feelings and "do I love myself."

When it comes up, I don't think about it. I don't expel on it.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------

Eberling: I have a staying power. I hurt. My mind just churns around.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------

Question: How would you feel if you did something that you didn't know about?

Eberling: I would be lost in another world. If you are referring to my blackouts, I don't honestly think that I ever went into another personality

Question: What happens when you go into blackouts?

Eberling: It just hits me.... I can't recount every moment leading up to this feeling. It's like switching a light plate. A light switch.

------------------------------------------------------------------------

Eberling: To understand Richard a bit better. He always looks to tomorrow and feels the streets are littered with gold. Meaning all one has to do is to stoop over and pick it up.

------------------------------------------------------------------------

Question: Why do you refer to yourself in the third person, such as, "Richard thinks this," or "Richard says that"?

Eberling: I go through my writings and take the I's out on purpose. It's too pretentious.

Question: But why the third person like this... "Richard believes"? (Showing him)

Eberling: I do write strange. I know that. I don't know why. Sometimes I treat myself as a subject. Have I done that before?

They're trying to take things away from me. Things that have happened to me are most abnormal. I'm a very arrogant individual. I learned I come across as arrogant- but I'm not really. The average person's never gone through this journey in life. The journey I embarked on -it's good, it's interesting. It's not dull by any means.

------------------------------------------------------------------------

Eberling: People have a secret side-a lot of people never show it, ever. ... I am very much to myself.

------------------------------------------------------------------------

Eberling: On Sheppard... it'll go to my grave. And I hate it.

------------------------------------------------------------------------

Eberling: If you are my downfall, I really don't care. If I go to the electric chair, that's no problem. It isn't important any more. Life isn't important any more.

------------------------------------------------------------------------

Eberling: The Sheppard answer is in front of the entire world. Nobody bothered to look.

|

Richard Eberling and the Sheppard Case

At the time of the Sheppard murder, twenty-five-year-old Richard Eberling operated a small company called Dick's Window Cleaning. Among his company's clients were Marilyn and Sam Sheppard. Eberling, by his own account, barely knew Sam , but developed a fairly close relationship with Marilyn Sheppard. He recalled having brownies and milk with Marilyn and Chip in the Sheppard home. His comments also suggest he found Marilyn sexually attractive: "Oh, she had that California look. Tight little brief shorts and a very little blouse. She was immaculate, all in white."

In 1959, Eberling was arrested for larceny after a client of his reported money stolen and suggested him as the likely criminal. A search of Eberling's home turned up wads of cash and jewelry. Among the items recovered by police was a cocktail ring owned by Marilyn Sheppard. During questioning following his arrest, police asked--playing a hunch, perhaps--why his blood was found in the Sheppard home following Marilyn's murder (in fact, his blood had not been found). Much to the surprise of his interrogators, Eberling said that two days before the murder, while washing windows at the Sheppard home, he had cut a finger while installing screen windows. Eberling's answer made police sufficiently suspicious that they pushed him to take a lie detector test and answer questions about the Sheppard murder. Eberling indicated his willingness to do so. In November, Eberling took a polygraph test. His examiner, A. S. Kimball, concluded that Eberling did not show deception when he said that he did not kill Marilyn Sheppard. Later, other polygraph experts reviewing the data would call the results "inconclusive."

Not Very "Bushy-Haired"

Mugshots of Richard Eberling following his arrest for larceny in 1959. Although not bushy-haired, he was known to have worn toupees.

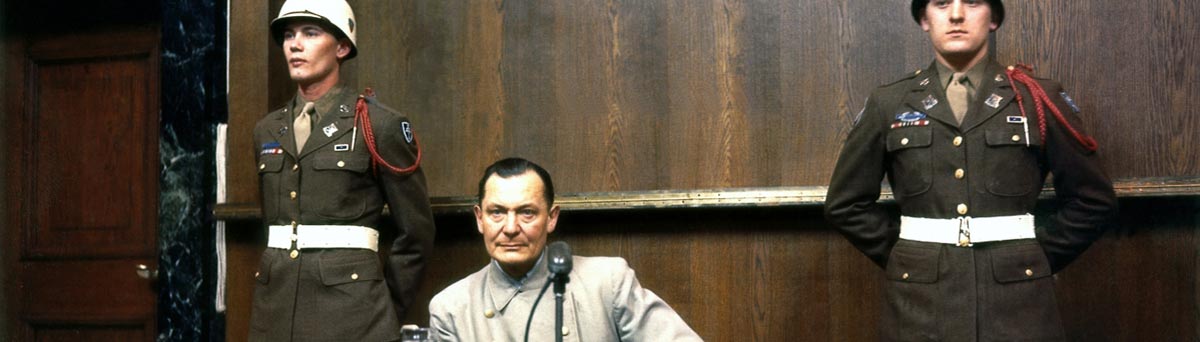

In the 1966 re-trial of Sam Sheppard, defense attorney F. Lee Bailey chose not to focus on Eberling as a suspect in the Sheppard murder. A strong believer in polygraph tests, Bailey assumed him cleared by virtue of his 1959 test. Instead, Bailey suggested that the murder was probably committed by Sheppard friends, Spencer and Esther Houk--with Esther's motivation being that Marilyn was having an affair with Spencer. Bailey actually called Eberling to the stand as a defense witness in the 1966 trial. Testifying only feet away from Sam Sheppard, Sam never suggested, "That's the man--that's the guy I wrestled with and who knocked me out twelve years ago."

Following a fine and a ninety-day suspended sentence for grand larceny, Eberling made a rather remarkable recovery that would catapult him into Cleveland's social elite. Cleveland's Republican mayor, Ralph Perk, had hired Eberling's partner, Obie Henderson, as a personal assistant. Though Obie's relationship with the mayor, Eberling succeeded in convincing the mayor's wife that she should hire him to decorate her home. Soon Eberling's interior decorating business took off, and he began hosting elaborate parties and landing ever richer clients. In 1973, he won a contract to restore Cleveland's historic City Hall. (By 1977, however, his arrogance had made enemies, and he was fired by new Cleveland mayor--and 2004 Democratic presidential candidate--Dennis Kucinich.)

As would eventually become clear, Eberling's criminal ways had not ended with his arrest for grand larceny in 1959. He committed elaborate insurance fraud. He befrauded elderly women. He even killed.

One person he killed was Ethel May Durkin, an elderly widow. (Some also suspect Eberling in the death of Durkin's sister, Myrtle Fray, who was brutally beaten on the head and strangled in her bed on May 20, 1962--a murder similar in many respects to the Sheppard murder.) In the late-1970s, Eberling became a nurse's aide for Durkin. Over time, Durkin came to trust Eberling and paid him handsomely. Around 1981, Ebrling revealed he was constructing a new will for "the old bat." On November 15, 1983, paramedics raced to the home of Ethel May Durkin to discover her facedown and comatose on her hardwood floor. Eberling, who identified himself as her nephew, told paramedics she had been walking, then fell face forward on to the floor. The nature of her injuries, and what medical evidence suggested was a lengthy delay between the injury and the emergency call, raised suspicion. Eventually, what started as an insurance investigation turned into a murder investigation. Eberling was convicted of forgery, theft, and aggravated murder in July 1989.

Eberling's conviction led to renewed interest in him as the possible murderer of Marilyn Sheppard. Many people suggested that Eberling's background as an illegitimate child who had been abandoned by his parents (he never met his father) fit the profile of someone who might brutally murder a beautiful young woman like Marilyn. Sam's brother, psychiatrist Dr. Steve Sheppard, suggested that Eberling might have released his "violent jealousy" of the successful Sheppard family through his attack on Marilyn.

In the years that followed, persons investigating the Sheppard case, such as James Neff, author of The Wrong Man, spent many hours interviewing Eberling in the hopes of gaining a confession to the Sheppard killing. Ultimately, he would disappoint, but some of his remarks might be seen as tantalizingly close to admissions of guilt. Neff reported, for example, that Eberling said he "fully expected" to be convicted of murdering Marilyn back in 1954. He complained that Sam Sheppard, who he called "a prick," ignored him. Most tellingly, Neff contends, Eberling, in an interview conducted shortly before his death in prison in 1998, described finding himself in the bloody bedroom of Marilyn Sheppard: "My God, I had never seen anything like it. I got out of there."

Despite the suspicion raised by Eberling's comments on the Sheppard case, and despite evidence produced by experts hired in Sam Sheppard's wrongful imprisonment suit suggesting a likelihood of Eberling's blood being present on the closet door next to the bloody Marilyn Sheppard, a civil jury in Cleveland in 2000 found for the county and against Sheppard. The jury, it seemed, still believed Sam Sheppard to be the more likely killer.

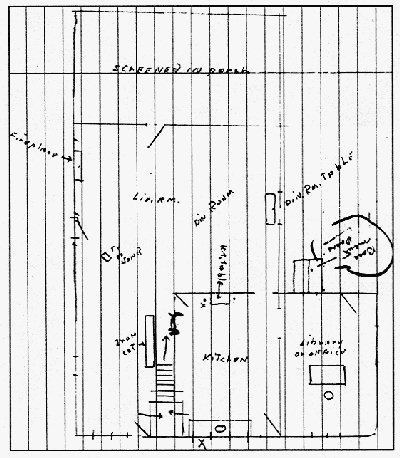

Floorplan of Sheppard home, as drawn from memory by Richard Eberling in 1992. Eberling marked the basement entrance to the home, which was ignored on the police sketch of the home. (Source: Cooper and Sheppard, Mockery of Justice (1995).) Facts Suggesting Eberling as a Suspect in the Sheppard Murder

(As outlined in Sam Reese Sheppard's Petition for a Declaration of Innocence,

filed October 19, 1995)

Richard Eberling, when arrested for a series of burglaries and thefts in 1959 (including the theft of Marilyn Sheppard's ring from the home of Dr. Sheppard's brother), disclosed that he had cut his hand washing windows at the Sheppard home, but gave conflicting times and dates as to when that supposedly occurred. In 1990, investigators tracked down a co-worker of Eberling who insisted that he, not Eberling washed the windows at the Sheppard home in the days before the murder. Incidentally, Eberling was not interrogated by police at the time of the murder, and in 1959, when Eberling was in custody, police were told to drop the matter by Coroner Gerber, Dr. Sheppard's principal accuser, as well as John T. Corrigan, the County Prosecutor.

A Scientific Investigation Unit report, also never disclosed by the prosecution, reveals that there was fresh evidence of forcible entry through the cellar door. The finding was significant enough to require a plasticine impression of the damaged doorway. Yet, the prosecution's most powerful argument against Dr. Sheppard was that there was no evidence of a break-in, and that Dr. Sheppard was the only one in the house at the time of the murder. That theory can now be debunked because the killer entered through the basement, an entry only known to a small number of people, including Eberling.

The re-investigation focused on Richard Eberling as a suspect, who is now serving a life imprisonment for the murder of Ethel Durkin. Eberling has a long and documented history of psychosis and psychopathic symptoms, beginning with neurological impairment as a child. His medical, psychological, and behavioral patterns are consistent with those of disturbed and even serial killers. The investigation reveals other unsolved killings of women, including the sisters of Ms. Durkin and others, with striking similarities to, the Sheppard murder. Eberling was obsessed with Marilyn Sheppard as indicated by his focus on owning her ring. He was a jewel thief and burglar, and on the' night of the murder, jewelry and cash were taken from the home. He was jealous of the Sheppard’s and their success in life, and the family he never had. He hated Dr. Sheppard for his athletic accomplishments, and two athletic trophies were smashed to the floor on the night of the murder, evidence of hostility and hatred. Eberling had a remarkable knowledge of the description of the property and the furnishings, and as of 1992, was able to draw an architecturally accurate drawing of the property. He cannot truthfully account for his whereabouts at the time of the murder. He fits all the available descriptions of the killer, including the build, the height, the large head, and the use of wigs. The police drawings derived from eyewitnesses who saw a man near the Sheppard home that evening, reveal a similarity to Eberling. Finally, Eberling, who granted a number of interviews and corresponded with Cynthia Cooper since 1992, has been obsessed with the Sheppard murder case and Marilyn Sheppard herself, and has made statements such as "why do women fight back when they are raped?" or "I'm looking at her now and she doesn't look pregnant." There is evidence that Marilyn Sheppard was sexually assaulted, as inferred by her nightgown pushed above her abdomen, yet this aspect was never pursued by the police.

The evidence will show that Eberling had motive, opportunity, identity, and access to kill Marilyn Sheppard.

|