Gunpowder Plot

The Gunpowder Plot Treason Trials (1606): An Account

Please to remember the Fifth of November

Gunpowder Treason and Plot.

We know no reason why Gunpowder Treason

Should ever be forgot.

—Translation of “In Quintum Novembris” (“On the Fifth of November”) by John Milton (1626).

Few trials have better stood the test of time than the Gunpowder Plot treason trials of 1606. Even today, bonfires are lighted in celebration all across England on November 5, Guy Fawkes Day, the day on which in 1605 one of the Gunpowder plotters, Guy Fawkes, was discovered lurking in the cellar below Westminster Palace, where he intended the next morning to light a large stockpile of gunpowder—when King James, Queen Anne, and Prince Henry would all be attending the long-delayed opening session of Parliament.

The Gunpowder Plot, and the trials that followed, can only be understood in the context of the time. A time when English Catholics faced cruel persecution from Protestant authorities. A time when Catholic hopes for outside intervention from Spain or other Catholic nations were dashed. A time when a band of Catholic extremists might decide that blowing about Parliament, and the King along with it, was worth the risk.

Background: A Religiously-Divided Nation

Before the 16th century, England was, like other European nations, a Roman Catholic country. Any citizen who publicly questioned the teachings of the Catholic Church was deemed a heretic and subject to punishment.

Martin Luther and the Reformation, with its origins in 1517 in Germany, challenged some of the practices of the Catholic Church and the Protestant movement rapidly gained adherents, primarily across norther Europe. England’s break with Rome came in 1534 when King Henry VIII, incensed that the Pope refused to grant him an annulment from the marriage to his first wife, Catherine of Aragon, thus allowing him to marry the object of his infatuation, Ann Bolelyn, declared himself the Supreme Head of the Church of England. King Henry VIII closed England’s monasteries and stripped them of their lands and assets. Henry’s son, King Edward VI, continued to push Protestant reforms during his short six-year reign from 1547 to 1553.

With Edward’s death, his sister Mary, a staunch Roman Catholic, became Queen. Queen Mary attempted to reverse the Reformation in England. During her rule, Protestants faced persecution and outspoken Protestant figures, from churchmen to ordinary citizens, faced punishments ranging from imprisonment to being burned at the stake.

When Queen Mary died at age 42 in 1558, England again lurched back toward Protestantism and persecution under the rule of Queen Elizabeth I. Attendance at Protestant churches became mandatory and Catholics wishing to practice their religion were again forced underground.

Religious tension and persecution of Catholics in England heated up following a failed 1569 plot to assassinate Queen Elizabeth and replace her with her cousin, the Catholic Mary Queen of Scots. Tensions rose further the following year when Pope Pius V excommunicated Elizabeth and absolved all her subjects from allegiance to her. The Pope’s action had the unsurprising effect of convincing Elizabeth to stiffen penalties and clamp down more forcefully on English Catholics. Internationally, Catholic Spain and England were in constant conflict and on the Continent, Protestant English were horrified by reports of Catholics atrocities, including massacres of Protestants in France and Antwerp. English Catholics came to be viewed as a serious national security threat – an ‘enemy within.’ Priests and lay Catholics soon filled every prison in the country.

It was a crime for priest to say Mass. Catholics were prohibited from baptizing their children in the Catholic faith or sending them abroad to a Catholic country. Every Catholic was required to attend a Protestant church on Sundays. All office holders and clergy had to swear allegiance to the sovereign as head of the Church. Priests were charged with treason and drawn and quartered.

English Catholics during the late 1500s were divided. Some saw their religious beliefs as a private matter, practiced their religion discreetly in their own home, and urged loyalty to the Crown. Other Catholics, called “recusants,” considered the situation intolerable and some among them advocated direct action, including violence if necessary, to restore the right to practice their religion more openly.

In March of 1603, Queen Elizabeth, in her seventieth year and childless and without consort, was depressed, weak, and dying. The Councilors of State gathered at Richmond Palace to make a momentous decision. They would decide who would be the next ruler of England. The Councilors chose as Elizabeth’s successor King James of Scotland, whose grandmother was a Tudor princess. When death came to the Queen on the morning of March 24, the Councilors drafted a document proclaiming James King of England.

The choice of James to be the new king was welcomed by English Catholics, hopeful that the Catholicism of James’ mother, Mary Queen of Scots’, would lead King James to lift the heavy penalties imposed on Catholics during the reign of Elizabeth. They also took hope from the fact that James’ wife, Queen Anne, was a privately practicing Catholic. Some even allowed themselves to imagine that James himself might convert to Catholicism. Adding to Catholic hopes, Pope Clement VIII extended his good wishes toward the new king. In April, Father Henry Garnet, the Jesuit Superior of England, called it “a golden time,” one of “unexpected freedom” and for “great hope” of “toleration” from English authorities.

But Catholics in England were disappointed. There was a large gap between their hopes and reality. King James never had any intention of becoming Catholic. In a letter, James wrote that he had no trouble with his subjects having “a diversity of opinions about religion,” but added, “I should be sorry that Catholics should so multiply that they might be able to practice their old principles on us.” And, it turned out, in the early period of James’ reign his relatively lenient policies did have the effect, according to a finding by Parliament in 1606, of multiplying the number of priests in England from one hundred to one thousand.

One year after his coronation, King James began to take a harsher line against Catholics. In 1604, he declared his “utter detestation” of Catholicism and all of its “superstitions.” James confirmed most of the harsh anti-Catholic laws of the previous reign. In April 1604, a bill was introduced in Parliament that would declare all Catholics to be outlaws. The next month, a group of Catholic fanatics began plotting.

The Gunpowder Plot

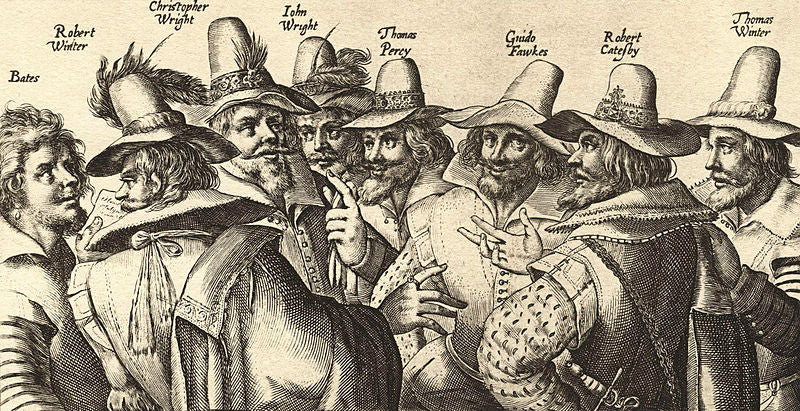

The origins of the Gunpowder Plot can be traced to a meeting at a London inn called the Duck and Drake on Sunday, May 20, 1604. Five conspirators attended, but their number would eventually grow to thirteen. The prime mover was Robert (“Robin”) Catesby, a handsome, charismatic young man, loved by friends and family alike. He had a passion for theology and considered himself a man of action. The other original conspirators included Robin’s cousin, Tom Wintour, Jack Wright and his brother-in-law Thomas Percy, and the man who history would make the face of the Gunpowder Plot, Guido (“Guy”) Fawkes. . .Continued