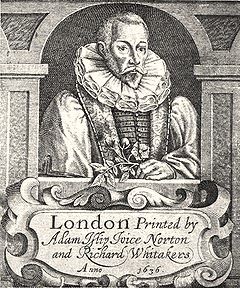

Father John Gerard's (1564 - 1637) A Narrative of the Gunpowder Plot

THE PREFACE [omitted]

CHAPTER II. [omitted]

THE STATE OF PERSECUTED CATHOLICS AT THE QUEEN*S

DEATH AND THE KING'S ENTRY, WITH THEIR HOPES

OF RELAXATION BY HIM, WHEREOF THEY FAILED.

CHAPTER III.

HOW UPON THESE AND THE LIKE MOTIVES DIVERS

GENTLEMEN DID CONSPIRE AND CONCLUDE UPON

SOME VIOLENT REMEDY.

BY that which hath been set down in the former chapter, every prudent man will easily conceive what was like to be the sense and feeling of all Catholics in this so great increase of their long-endured afflictions, in this utter despair of any help from His Majesty, (in whose promised clemency all their hopes were placed), and in a certain expectation of other most cruel and newly-invented laws to be further imposed upon them at the next Parliament as against traitors not worthy to live in a commonwealth, and as such already published in books framed and printed by authority, and so censured and pronounced by the King himself. In what other state could they be but a general and most afflicting desolation, and as the Prophet Esay Esay saith, " Omne caput languidum et omne cor mcerens " , from the highest to the lowest.

But the cogitations of men, as they were all much afflicted in such an inundation of evils upon them without hope of ease or end, so yet no doubt they were very dif- ferent according to the divers states of minds in plenty or penury of grace, and partly also according to their different natures and dispositions, some more able and apt than others to bear injuries with patience. We know right well, and all England will witness with us, that the greatest part by much did follow the example and exhortation of the Religious and Priests that were their guides, moving them and leading them by their own practice to make their refuge unto God in so great extremities, " Qui nunquam deserit sperantes in se;" " Nee patietur nos tentari supra id quod possumus, sed faciet cum tentatione proventum ut i possimus sustinere." " Immo modicum passes ipse proficiet, confirmabit, solidabitque." This we found to be believed practically by most, and followed as faithfully, preparing themselves by more often frequentation of the Sacraments, by more fervent prayer, and by perfect resignation of their will to God, against the cloud that was like to cover them, and the shower that might be expected would pour down upon them after the Parliament, unto which all the chief Puritans of the land were called, and only they or their friends selected out of every shire to be the framers of the laws, which thereby we might easily know were chiefly intended and prepared against us. But in so great a multitude all are not so perfect, some few fainted in courage, and, as St. Cyprian noteth of his times, did offer themselves unto the persecutors before they felt the chief force of the blow that was to be expected.

Others again (as since it hath appeared) were much different from these, and ran headlong into a contrary error. For being resolved never to yield or forsake their faith, they had not patience and longanimity to expect the Providence of God, " qui attingit a fine usque ad finem fortiter et disponit omnia suaviter." They would not endure to see their brethren so trodden upon by every Puritan, so made a prey to every needy follower of the Court or servant to a Councillor, so presented and pursued by every churchwarden and minister, so hauled to every sessions when the Justices list to meet, so wronged on every side by the process of excommunication or out- lawry, and forced to seek for their own by law, and then also to be denied law, because they were Papists ; finally both themselves and all others to be denounced traitors, and designed to the slaughter. These things they would not endure now to begin afresh after so long endurance, .and therefore began amongst themselves to consult what remedy they might apply to all these evils (and few greater than these by the daily destruction of innumerable souls, as they alleged at their death), so that it seems they did not so much respect what the remedy were, or how it might be procured, as that it might be sure and speedy, to wit, to take effect before the end of the Parliament from whence they seemed to expect their greatest harm.

And this I do guess to have been the likeliest motive, to make that stratagem of the Parliament House to come into their head, unless perhaps they did think it was impossible for them to prevail any other way. Now peace being concluded by other Princes, they could not expect any sufficient aid from them. And they saw that other Princes were willing with the peace in regard of their own affairs (which might be cause sufficient), although there the peace of Catholics was not included ; yea presently upon the concluding of that, they saw and felt that the persecution began afresh and in far worse manner than before (as in the precedent chapters hath been related), yea they found that their case would not be understood in many Princes' Courts, but rather the Ambassadors and other instruments employed by their persecutors believed, than their case credited when it was laid down by witnesses of unstained integrity. And seeing for these causes no hope of help from others, they knew well that of themselves by open rising in field they were not able to resist and repel the force of the whole State, both because all Catholics would not join in those courses, and because both Protestants and Puritans would then join together against them ; therefore this public course being not probable to take effect, it is like they fell to search out what private way might be within their power and yet might be effectual. And then, as it seems by their confessions (made after to the Council), Mr. Catesby proposed that fatal and final course of overthrowing the Parliament House, alleging for his reason that which before I gathered to be his mind out of his own words : that so, said he, we may deliver our country from the servitude she is in> and at one instant deliver us from all our bonds, and although we can have no foreign help, yet so may we plant again the Catholic religion in our country. Thus you may see how good desires may be followed by unfit means, and how much a man may be deceived when he doth follow but his own ways, how good or great soever the motives be or the wished effect of that he goetli about, for u non est faciendum malum ut inde eveniat bonum."

And when one of his companions, called Mr. Winter, proposed that the matter was so great and imported so many,, that it would be well considered of, Mr. Catesby answered,. "The nature of the disease was such that it required so sharp a remedy, and that the Parliament was the place where all the laws had been made against Catholics, and therefore the fittest for the makers of those laws there to receive their punishment, especially there being then chosen all the Puritans of the realm, of purpose to make much more cruel laws than before ; so that at one blow they should cut off all the greatest enemies of God's Church, and the greatest persecutors both of their souls and bodies, which they could not do by any other possible means ; and not doing that, they would never prevail nor save the whole country from destruction of their souls. nor their brethren and themselves from slaughter of their bodies." Thus he. This, therefore, seeming probable and pious to their deceived judgments, they fell upon that conclusion, that they would prepare for it as soon as they could, but in such secret manner that no living creature for no cause should understand of their designments but themselves that then consulted, who were but five in number, and they would take an oath of secrecy upon a Primer to that effect. Only some months after, when they found some more help was needful for them, they con- cluded that three of the five, whereof Mr. Catesby and another of the chiefest to be two, might impart it to some other chosen person to draw him into the action. So great care they had, that it might not be so much as suspected by other Catholics, and especially they meant to keep it from their ghostly Fathers and all kind of Religious men or Priests, knowing well they should never have their assent to an action of that nature. And besides, for that they had no doubt at that time or any scruple in the matter for the causes before alleged, gathered out of Mr. Catesby his words, though afterwards when the matter depended much longer than they expected, upon some occasion or other that belike was offered, they began to doubt of one circumstance, and then sought resolution, but in such cunning and close manner, as shall afterwards appear in the process of the story. And thirdly, for that they feared their ghostly Fathers would assuredly draw them out of that course if they should have understanding of it, which to be a principal cause of their keeping the matter so secret from them, may appear by the speeches which Sir Everard Digby used afterwards at the time of his arraignment.

The five that concluded first upon this preposterous Plot of Powder were these, Mr. Robert Catesby, Mr. Thomas Percy, Mr. Thomas Winter, Mr. John Wright, and Mr. Guy Fawks, as appeareth by the confession of the said Mr. Thomas Winter, out of whose examinations with the others that were made in the time of their imprisonment, I must gather and set down all that is to be said or collected of their purposes and proceedings in this heady enterprise. For that as I have said, they kept it so wholly secret from all men, that until their flight and apprehension it was not known to any that such a matter was in hand, and then there could none have access unto them to learn the particulars. But we must be contented with that which some of those that lived to be examined, did therein deliver. Only for that some of their servants that were up in arms with them in the country did afterwards escape, somewhat might be learned by them of their carriage in their last extremities, and some such words as they then uttered, whereby their mind in the whole matter is something the more opened, and all as I have heard then I will faithfully relate.

But first that these first conspirators may be the better known, together with the matter and manner of their conspiracy, it shall be good to let you see in particular what the persons were.

Mr. Catesby (who as it seems by many circumstances was the first inventor and the chiefest furtherer of the Plot) was a gentleman of an ancient and great family in England, whose chief estate and dwelling was in Warwickshire, though his ancestors had much living in other shires also. Some of his ancestors had borne great sway in England. But commonly the greatest men are not the best. Some others have been of great esteem for virtue, as namely one knight of his house (I take it some four or five descents ago) was commonly known and called in all the country, "good Sir William Catesby/' of whom this memorable thing is recorded ; that when he had lived long in the fear of God and works of charity, one time as he was walking in the fields, his good Angel appeared and showed him the anatomy of a dead man and willed him to prepare him, for he should die by such a time. The good knight presently accepting of the message willingly, recommended himself with a fervent prayer unto our Blessed Lady in that place and then went home and settled all his business both towards God and the world, and died at his time appointed. This story is painted upon a wall in the church of Ashby, where that knight and other of Mr. Catesby's ancestors lie buried. Myself have both seen the pictures and read the prayer in that place.

Mr. Catesby his estate in his father's time was great, above 3,ooo/. a year, which now were worth much more; but Sir William Catesby, his father, being a Catholic and often in prison for his faith, suffered many losses and much impaired his estate. This son of his when he came to the living was very wild, and as he kept company with the best noblemen of the land, so he spent much above his rate and so wasted also good part of his living. Some four or five years before Queen Elizabeth died, he was reclaimed from his wild courses and became a Catholic, unto which he had always been inclined in opinion, though not in practice. But after this time he left his swearing and excess of play and apparel and all wild company and began to use daily practices of religion instead of them, insomuch that his former companions did marvel to see him so changed ; for he concealed his being a Catholic a long time. After that, about three years before the Queen's death, when the Earl of Essex did intend and attempt by force to put down some of those that ruled the State and meant (as it is thought) to have brought in His Majesty that now is into the realm at that time, and to that end combined many noblemen and gentlemen together in the enterprise, then was Mr. Catesby a principal man in the action, having first received a faithful promise from the Earl of toleration at least for all Catholics : yea and to that end he procured some other Catholics to join also.

In that business, though it was weakly performed by those that had the chief carriage, especially that Earl of Essex, yet did Mr. Catesby show such valour and fought so long and stoutly, as divers afterwards of those swordsmen did exceedingly esteem him and follow him in regard thereof, and only commended Sir Christopher Blunt and him, both which were often compared together, as well for their performance, as for the hurts they received ; though Mr. Catesby kept his very secret in prison, being in hope to escape with a ransom, as he did, paying 2,ooo/., but it cost him 3,ooo/. before he got out. All which I therefore relate, as a chief means of his getting aid and followers in the other enterprise following, in which although he and his complices did us as great a wrong as might be, and took themselves a most wrong course in their deceived zeal ; yet I will not wrong them with false reports in anything, nor wrong the reader so much, as not to let him plainly know what kind of men they were, and to that end do relate both their good and their evil.

When Mr. Catesby was cured of his hurts and had paid his ransom and procured his liberty, he was so much esteemed and respected in all companies of such as are counted there swordsmen or men of action, that few were in the opinions of most men preferred before him, and he increased much his acquaintance and friends. Upon which occasion he then began to labour to win many to the Catholic faith, which he performed, and brought many to be Catholics of the better sort, and was a continual means of helping others to often frequentation of the Sacraments, to which end he kept and maintained Priests in several places. And for himself he duly received the Blessed Sacrament every Sunday and Festival-day, and grew to such a composition of manners and carriage, to such a care in his speech (that it might never be hurtful to others, but taking all occasions of doing good), to such a zealous course of life, both for the cause in general and every particular person whom he could help in God's service, as that he grew to be very much respected by most of the better and graver sort of Catholics, and of Priests, and Religious also, whom he did much satisfy in the care of his conscience ; so that it might plainly appear he had the fear of God joined with an earnest desire to serve Him. And so no marvel though many Priests did know him and were often in his company. He was moreover very wise and of great judgment, though his utterance not so good. Besides he was so liberal and apt to help all sorts, as it got him much love. He was of person above two yards high and, though slender, yet as well proportioned to his height as any man one should see. His age (I take it) at his death was about thirty-five, or thereabouts. And to do him right, if he had not fallen into this foul action and followed his own judgment in it (to the hurt and scandal of many), asking no advice but of his own reasons deceived and blinded under the shadow of zeal ; if, I say, it had not been for this, he had truly been a man worthy to be highly esteemed and prized in any commonwealth.

Mr. Thomas Percy was of the name and kindred of one of the ancientest and greatest Earls in England, though I think he was not very near in blood, although they called him cousin. His estate was not great, depending most upon the same Earl that now is of the house of Percies, under whom he had the keeping of a castle and the receiving of his rents, with the overlooking and command of his tenants in those parts. For the most part of his youth he had been very wild more than ordinary, and much given to fighting, so much that it was noted in him and in Mr. John Wright (whose sister he afterwards married) that if they had heard of any man in the country to be esteemed more valiant and resolute than others, one or the other of them would surely have picked some quarrel against him and fought with him to have made trial of his valour. This Mr. Percy was for most of his time affected to Catholics and a friend unto them, and did labour and was the means to get some out of prison ; but himself far from professing the same, or following their counsel or example, until within five or six years before his death, and I think about the time of my Lord of Essex his enterprise he became Catholic ; for he was also one in the action and a very forward man, hoping that some ease at least would have come to Catholics by the means. After that he was much more reclaimed, and grew in time, by keeping Catholics' company, and often frequentation of the Sacraments, to leave all his old customs, and to live a very staid and sober life, and for a year or two before his death kept a Priest continually in the country to do good unto his family and neighbours, though himself came thither but at times, living for the most part in London, where he was made one of the Gentlemen Pensioners in Ordinary, and so continued till his death. He had a great wit and a very good delivery of his mind, and so was able to speak as well as most in the things wherein he had experience. He was tall, and of a very comely face and fashion ; of age near fifty, as I take it, for his head and beard was much changed white.

Mr. Thomas Winter was a younger brother of the house of Huddington, in the county of Worcester, whose eldest brother and another younger than himself were also brought after into the action by his means. This gentleman had spent his youth well as it seemed by the parts he had, for he was a reasonable good scholar, and able to talk in many matters of learning, but especially in philosophy or histories very well and judicially. He could speak both Latin, Italian, Spanish, and French. He had been a soldier both in Flanders, France, and, I think, against the Turk, and could discourse exceeding well of those matters. And was of such a wit, and so fine carriage, that he was of so pleasing conversation, desired much of the better sort, but an inseparable friend to Mr. Robert Catesby. He was of mean stature, but strong and comely and very valiant, about thirty-three years old or somewhat more. His means were not great, but he lived in good sort, and with the best. He was very devout and zealous In his faith, and careful to come often to the Sacraments, and of very grave and discreet carriage, offensive to no man, and fit for any employment. I wish therefore he had been employed in some better business.

Mr. John Wright was a gentleman of Yorkshire, not born to any great fortune, but lived always in place and company of the better sort. In his youth and for the most of his time very wild and disposed to fighting and trial of his manhood, as I touched before. He became Catholic about the time of my Lord of Essex his attempt, in which he was ; and after that time kept much with Mr. Catesby and some other gentlemen of his friends and acquaintance. He grew to be staid and of good sober carriage after he was Catholic, and kept house in Lincolnshire, where he had Priests come often, both for his spiritual comfort and their own in corporal helps. He was about forty years old, a strong and a stout man, and of a very good wit, though slow of speech ; much loved by Mr. Catesby for his valour and secrecy in carriage of any business, which, I suppose, was the cause why he was one of the first acquainted with this unfortunate enterprise.

Mr. Guido Faulks spent most of his time in the wars of Flanders, which is the cause that he was less known here in England, but those that have known him do affirm that as he did bear office in the camp under the English coronell on the Catholic side, so he was a man every way deserving it whilst he stayed there, both for devotion more than is ordinarily found in soldiers, and especially for his skill in martial affairs and great valour, for which he was there much esteemed. And that was the cause, as it may be thought, why Mr. Catesby and the rest of the conspirators cast their eyes upon him before others, when they desired one out of Flanders to be their assistant.

But would to God these gentlemen had used their talents better and employed them to the service of God and their country, for which they were given, and not to the offence of the one and destruction of the other, as we find nowto our great increase of grief amidst the rest of our manycalamities and heavy burthen of persecution, of which the memory of this matter is not the least. Undoubtedly they were men of able parts to perform much in God's service, and so it is like they would have continued as they had begun if they would have feared sufficiently their own fancies, and followed the grave example and advice of those from whom they sought for help in all other matters that concerned their soul. And yet at length they began to doubt in some points of this also, as shall appear in the chapter following.

CHAPTER IV.

HOW AFTER THEY HAD BEGUN THEIR ENTERPRISE,

THEY FELL INTO SOME SCRUPLE,

AND WENT ABOUT TO SATISFY THEIR CONSCIENCE BY ASKING QUESTIONS AFAR OFF, OF LEARNED MEN, WITHOUT OPENING THE CASE.

IT appeareth by the confession which Mr. Thomas Winter made unto the Lords of the Council, being published in print by order from the said Council, that these gentlemen having concluded upon this course of violent remedy (because they resolved to undertake it as their last refuge and remedy of all the evils they sought to prevent), Mr. Catesby, who first proposed this fatal blow to be given to the Parliament House, did also first propose unto them the last trial which he thought likely to prevail for redress of those evils by quiet means ; and to use his own words, there related by Mr. Winter, " First (said he to Mr, Thomas Winter) because we will leave no peaceable and quiet way untried, you shall go over and inform the Constable (who was then upon his coming in) of the state of the Catholics here in England, entreating him to solicit His Majesty at his coming hither, that the Penal Laws may be recalled, and we admitted into the rank of his other subjects." Mr. Winter went over and delivered his message unto the Constable as in the name of all the Catholics of England, whose answer was, that he had strict command from His Majesty of Spain to do all good offices for the Catholics ; and for his own part, he thought himself bound in conscience so to do, and that no good occasion should be omitted. Thus much the Constable promised at that time, and no doubt performed it both wisely and charitably in what he could. But it is an easy matter to satisfy with hopes of future favours, when he that receives the promises shall not be present to see the performance.

So soon as the peace was concluded, and the Constable [of Spain] departed, the stream of persecution began to run more violently than before. Searches were more frequent, the seizure of goods more ordinary and violent, the payment of 2O/. a month with the arrearages also were enacted, and (which terrified most) the Puritans, who were the chief men selected and summoned for the Parliament, were so full of their designments against Catholics, that they could not choose but [cast out great threats] against them in every place where they came; some affirming they would now set up their rest and have their will of Catholics ; some that they would leave no Catholics in England after a while ; others that they hoped to see them all hanged ere it were long. Yea, I know a town myself whither some Puritans came to seize some goods of Catholics long before the Parliament, where the party whose goods were taken, complaining of the rigour in the manner of proceeding, the officers answered, "They hoped to see all the Catholics' throats cut shortly, therefore this was nothing." Things therefore standing in these terms with Catholics, these gentlemen resolved to expect no further trials, but, as I said, concluded upon their intended stratagem, bound each other by oath to the highest degree of secrecy, and so it seems they went about their business, never fearing any fault in the thing itself, nor fall that might come to Catholics by their error ; and thus it continued for a good space with them.

They hired a house by the water side (as may appear in Mr. Winter's confession) where they might first land their powder when they had bought it, and from whence they might easily transport it by boat also unto the place appointed, which was a house close by the Parliament House, hired by Mr. Thomas Percy, as a fit residence for himself near the Court, being Pensioner, and to wait daily in his quarters. And Mr. Faulks went as his man to keep the house. In this house, to prevent occasions of often going out, because they would not seem to be many in the house, they bought baked meats and made provision at once for a long time. They began to work underground at such times as they could least be heard, and wrought the mine until they came to the wall of the Parliament House, which finding to be hard stone, they were long about a little progress, and were to be more wary than before in respect of the noise. Whilst they were thus together, and proceeding daily as they might, they had leisure, saith Mr. Winter, to fashion all their business, and to discourse of .all things that were to be done in the matter, whereby it may seem their first resolution of the thing itself was sudden, and such as young heads and forward minds do often bring forth, without due consideration of circumstances and likely events, which would not have been if they had asked counsel in the cause ; but rather, if the matter had been of that quality that it had been fit to have proceeded in it (as this was most unfit of all others), then would all the circumstance of importance have been foreseen beforehand, and all likely events forecast, and according to them the resolution left off or undertaken. But these gentlemen, as it seems then, with that leisure and opportunity of being so much in private together, began to fashion their business, after they had begun the enterprise. Then they began to think how they should get into their hands the next heir, whom they might set up and strengthen against the meaner sort of Puritans that would be left ; so that his authority being used in his nonage, the Catholic religion might be erected, and he so brought up, as that he would at his full years be a patron of the same. And Mr. Percy undertook that charge, being one that might best be seen in the Court, in regard of his place. Then they discoursed what foreign Princes they should acquaint with the business, in respect of their help after against the heretics, if they did stand out long. And they resolved to acquaint none ; first, because they could not oblige them by oath to secrecy, so as they might be sufficiently assured thereof, which they esteemed the most necessary point of all others, and the strength of the whole business ; secondly, for that it seemed they were doubtful the matter would be misliked by other Princes, as indeed they had cause to think it, not likely only, but certain ; and so no doubt they would have found it, if it had been imparted to any, especially if the least notice had come unto His Holiness, who had ever showed a special care of our King, and had great hope that in time he would do well both for himself and his country. Then also they began to think what Lords they should save out of the Parliament. And first they resolved they would save as many as they could. Then they descended more into particulars, to consider whom they might draw out of the danger, without danger of discovering unto them the cause why, or so that they might have the least suspicion of the matter intended.

And here, belike, finding it would be very hard to save so many as they desired, and yet withal to save the secrecy of their enterprise (in which consisted the safety of themselves and of the cause), here it is very likely they began to have that scruple in which after- wards they sought to satisfy their conscience, but not in right and plain matter as they should, by explaining the case of which they demanded, but afar off, as a thing by chance coming into their mind, and concerning rather a point of warlike affairs in general, than any particular intention of theirs at that time to be put in practice. For whilst they were in the middle of their discourses (saith Mr. Winter), understanding that the Parlia- ment should be anew adjourned, they left off their work for that time, and went to keep Christmas in several places, which was always their custom, to avoid suspicion. Then the chiefest of them took the present commodity offered by meeting with learned Priests that holy time, and meant to inform themselves of such doubts as were risen concerning the lawfulness of the business they had in hand. And, having a great opinion both of the learning and virtue of the Fathers of the Society, Mr. Catesby desired to get, by cunning means, the judgment of their Superior, so as he should never perceive to what end the question were asked. Therefore coming to Father Garnett, after much ordinary talk, and some time passed over after his arrival, one time he took occasion (upon some speech proposed about the wars in the Low Countries or such like) to ask how far it might be lawful for the party that hath the just quarrel to proceed in sacking or destroying a town of the enemy's or fortress when it is holden against them by strong hands. The Father answered that in a just war it was lawful for those that had right to wage battle against the enemies of their commonwealth, to authorize their captains or soldiers, as their officers, to annoy or destroy any town that is unjustly holden against them, and that such is the common doctrine of all Divines : in respect that every commonwealth must by the Law of Nature be sufficient for itself, and therefore as well able to repel injuries as to provide necessaries ; and that, as a private person may vim m repellere, so may the commonwealth do the like with so much more right as the whole is of more importance than a part ; which, if it were not true, it should follow that Nature had provided better for beasts than for men, furnishing them with natural weapons as well to offend as to defend themselves, which we see also they have a natural instinct to use, when the offence of the invader is necessary for their own defence. And therefore that it is not fit to think that God, Who by natural reason, doth provide in a more universal and more noble manner for men than by natural instinct for beasts, hath left any particular person, and much less a commonwealth, without sufficient means to defend and conserve itself; and therefore not without power to provide and use likely means to repel present injuries, and to repress known and hurtful enemies. And that, in all these, the head of the commonwealth may judge what is expedient and needful for the body thereof. Unto which Mr. Catesby answering that all this seemed to be plain in common reason, and the same also practised by all well-governed commonwealths that ever have been, were they never so pious or devout. But, said he, some put the greatest difficulty in the sackage of towns and overthrowing or drowning up of forts, which, in the Low Countries, and in all wars is endeavoured, when the fort cannot otherwise be surprised, and the same of great importance to be taken. How then those who have right to make the war may justify that destruction of the town or fort, wherein there be many innocents and young children, and some perhaps unchristened, which must needs perish withal ? Unto this the Father answered, that indeed therein was the greatest difficulty ; and that it was a thing could never be lawful in itself, to kill an innocent, for that the reason ceaseth in them for which the pain of death may be inflicted by authority, seeing the cause why a malefactor and enemy to the commonwealth may be put to death is in respect of the common good, which is to be preferred before his private (for otherwise, considering the thing only in itself, it were not lawful to put any man to death) ; and so because the malefactor doth in re gravi hinder the common good, therefore by the authority of the magistrate that impediment may be removed. But now, as for the innocent and good, their life is a help and furtherance to the common good, and therefore in no sort it can be lawful to kill or destroy an innocent. But, said Mr. Catesby, that is done ordinarily in the destruction of these forts I spake of. It is true, said the Father, it is there permitted, because it cannot be avoided ; but is done as per accidens, and not as a thing intended by or for itself, and so it is not unlawful. As if we were shot into the arm with a poisoned bullet, so that we could not escape with life unless we cut off our arm ; then per accidens we cut off our hand and fingers also which were sound, and yet being, at that time of danger, inseparably joined to the arm, lawful to be cut off, which it were not lawful otherwise to do without mortal sin. And such was the case of the town of Gabaa, and the other towns of the tribe of Benjamin, wherein many were destroyed that had not offended. With which Mr. Catesby seeming fully satisfied, brake presently into other talk, the Father at that time little imagining whereat he aimed, though afterwards, when the matter was known, he told some friends what had passed between by Mr. Catesby and him about this matter, and that he little suspected then he would so have applied the general doctrine of Divines to the practice of a private and so perilous a case, without expressing all particulars, which course may give occasion of great errors, as we see it did in this.

Now Mr. Catesby having found as much as he thought was needful for his purpose, related the same unto the rest of the conspirators, and all were animated in their proceedings without any further scruple for a long time, but applied all by their own divinity unto their own case, persuading themselves belike, that they had all the conditions of a lawful war with the Puritans and Protestant parties. First, a just cause, in defence of their goods, lives, and liberty, both of themselves and their brethren, and especially for the delivery and safety of so many thousand souls inthralled by sin and heresy ; secondly, they thought they found in themselves a right intention to suppress evil and erect and strengthen that which was good and needful ; thirdly, about authority to commence the same, I suppose they had most difficulty, and do not see how they could satisfy their own reason (much less the rules that are required in schools) in that behalf, seeing they did know so well, and had been so often told by the said Father Garnett and others of their spiritual guides, that His Holiness had given strict charge there should be nothing attempted against His Majesty [and the State], but that all Catholics should seek in patience to possess their souls, and thereby, and not by force, to plead for favour. I know not therefore from what ground they could imagine themselves to have authority, although in a far less matter. For it is not likely that they should think of the opinion of some that hold " quod defensio manualis cum sit de Jure Naturali non potest auferri per Superiorem vel contrarium praecipi." And besides, that is to be understood ipso conflictu, and not longe ante, as in this case of the Parliament.

But it is an easy matter for an earnest desire to draw a man's opinion after it, and so their great and unadvised zeal to remedy the wrongs done to Catholics both in soul and body, might perhaps make them think that this opportunity of the Parliament being omitted, they should never again have power or opportunity to defend the Catholic party. And that there was not sufficient access to inform Superiors of the case of Catholics, neither that their extremities were believed, and that if they were truly known, they neither would nor could be tolerated when remedy might be applied, in which they thought themselves as it were the officers and hands of the commonwealth, in whose hands and power it was then to perform it as they thought, but would not be so if they should ask counsel or leave of others, because so great a secret could not be kept in the mouths of many, and those not in like manner or measure affected to the business. Thus we may see how oftentimes it happens that a greedy affection and desire of the prey doth not let the bird consider or see the danger of the net which hangeth between the prey and it. And so as it is in too earnest pursuit of riches, that " qui volunt divites fieri incidunt in tentationem et in laqueum diaboli," 1 so in this case, their vehement desire of their prefixed end, did make them oversee a number of inconveniences and .perils both of soul and body, that did hang upon this lamentable enterprise, which they did afterwards find, and as I hope repented : and others for their fault have felt more at leisure since this matter happened.

But we that be innocent in the case, and were no ways accessary to the cause giving, must not repine at God's judgments, if He suffer us to be beaten for the error by others committed : Et si in vincula conjiciamur quasi mala operantes et ante reges et praesides ducamur quasi non existentes amici Caesaris, yet we must be comforted in the testimony of our own conscience, that we do hate all treason against our Prince as much as those that punish us for traitors, and would no ways have joined in this if we had known it, but our earnest endeavours against it should have given sufficient testimony of a contrary mind in us, as may and will appear in the chapter following was done by Father Garnett when he began to fear they had something in hand, although he could never guess or suspect so strange a practice as they were then in plotting or rather in perfecting to be performed.

CHAPTER V. [omitted]

HOW FATHER GARNETT BEGINNING TO SUSPECT SOMEWHAT BY CERTAIN GENERALITIES HE UNDERSTOOD OF THE GENTLEMEN,

WROTE DIVERS LETTERS TO ROME FOR PREVENTION OF REBELLION.

CHAPTER VI.

MOW IN THE MEAN SPACE, THE CONSPIRATORS PROCEEDED IN THEIR PURPOSE,

AND DREW IN MORE COMPLICES, AND WHAT THEY WERE.

WHILST the great persecution before recited did reign so much, and brought with it so many and so great afflictions upon all sorts of Catholics, as before you have read, and whilst Father Garnett did verily persuade himself that notwithstanding all those great difficulties, all was and would be borne with patience, until further order could be taken, and the same patient toleration publicly commanded which he had privately counselled ; these foresaid gentlemen who had commenced a course before that time which Father Garnett did little dream of, although they did bear him in hand whom they saw resolute for quiet courses, that they would expect until order came from authority, after their messenger had been heard, whom they had sent to explain their griefs according to his counsel, yet they, persuading themselves (as they afterwards affirmed to some that were with them, when they were in arms in the country, but were not taken with them) that if contrary order to their designments should come from higher authority (as they feared in likelihood it would, and therefore were loth to expect so long) that the same was only upon mistaking of their case or upon some hope perhaps His Holiness might have that things would be better with Catholics after a time, and that favour would be procured by fair means ; and this hope grounded upon promises from those that had deceived many with the like and never kept any yet that they made in that kind. They therefore, thinking themselves to have had so long trial hereof, would not be staid, as it seems, from their present purpose by future expectations, but proceeded in what way they had begun, and provided still more powder to such a quantity as made up in all thirty-six barrels, somebigger and some less ; all which they placed so in the cellar under the Parliament House, as must needs haveoverthrown the same and some other buildings also that had been near unto it, if it had been set on fire as wasintended ; especially having placed thereon many billets of wood to cover the same powder and some bars of iron also of purpose : all which being blown up with the powder, would have made sure to tear and rend the Parliament House in pieces.

Thus having disposed all things in the cellar as they would have them, they absented themselves much from thence ; because they would give no cause of note over that place more than others, whereof they were ever very careful. And so they had good cause, being men as likely to be noted by the State for men of action and performance, as any in the realm ; and then, being withal known to be resolute Catholics, their often meetings or haunting much to one place, especially near the Court, would not have been free from suspect. For the samecause also, during all the time they wrought in the mine or cellar, they would have but small company, and were but seven acquainted with the matter, all which I named before. Only one man of meaner condition they admitted there into the secret, to help them in making provision of their powder, and that was one Bates, a servant of Mr. Robert Catesby's, whom he had great opinion of for his long tried fidelity towards him, which the poor fellow continued even until he saw his master dead ; and then, it is like, his heart was dead withal, for he showed some fear after, when he was taken, which gave others occasion to work upon his weakness and to give some beginning of colour towards the accusation of divers that were not guilty in the matter, as shall afterwards appear. But these foresaid gentlemen having left the cellar, as they desired to find it, were then to seek for further helps wherewith to effect their designments when that act should be performed. For then their purpose was (saith Mr. Winter in his printed confession) to seize upon the person of the young Prince, if he were not in the Parliament House, which they much desired. But if he were, then upon the young Duke Charles, who then should be the next heir, and him they would erect, and with him and by his authority, the Catholic religion. If that did also fail them, then had they a resolution to take the Lady Elizabeth, who was in the keeping of the Lord Harrington in Warwickshire ; and so by one means or other, they would be certain to settle in the crown one of the true heirs unto the same. But to perform this part of their exploit required more hands and help than as yet they had at command. Wherefore they bethought themselves what help they might adjoin unto them in that great secret, without likely danger and yet with the assistance which they wanted, which partly required some more, men of strength both in mind and body ; but chiefly for supply of money, which if they had in readiness, and that placed in those countries where they meant to gather to a head, and where, for the most part, all sorts are either Catholic or affected to Catholics, they thought then they could want neither men nor any needful provision.

To this effect they first acquainted Mr. Ambrose Rookewood with the business, a gentleman of good worth in the county of Suffolk and of a very ancient family and himself the heir of the eldest house. This gentleman was brought up in Catholic religion from his infancy and was ever very devout. His parents also were very virtuous and suffered much persecution for their Faith, both in payment of money and loss of their goods and many other molestations ; yet was their house a continual receptacle for Priests, and a place wherein many other Catholics did often find great spiritual comfort, the house being a very fair great house and his living very sufficient. But that which moved them specially to make choice of Mr. Rookewood was, I suppose, not so much to have his help by his living as by his person, and some provision of horses, of which he had divers of the best : but for himself, he was known to be of great virtue and no less valour and very secret. He was also of very good parts otherwise as for writ and learning, having spent of his youth in study. He was at this time, as I take it, not past twenty-six or twentyseven years old and had married a gentlewoman of a great family, a virtuous Catholic also, by whom he had divers young children. Yet it seemed all those did little move him nor in any respect to his living or fortune, though he had enjoyed them but a little time ; whereby I do gather, they made a great account of this business, in respect whereof, it seems, they made account of nothing.

Next unto him was a Warwickshire gentleman, one Mr. John Grant, a man of sufficient estate for his own charge, and lived well in his country ; but of no great ability to help in the business, otherwise than by his acquaintance (being well beloved and allied in that country where they were chiefly to need help), But for his own person he was as fierce as a lion, of a very undaunted courage as could be found in a country : which mind of his he had often showed unto pursuivants and prowling companions, when they would come to his house- to search and ransack the same, as they did to divers of his neighbours. But he paid them so well for their labour not with crowns of gold but with cracked crowns sometimes, and with dry blows instead of drink and other good cheer, that they durst not visit him any more, unless they brought great store of help with them. Truth is, his mettle and manner of proceeding was so well known unto them, that it kept them very much in awe and himself in much quiet which he did the rather use, that he might with more safety keep a Priest in his house, which he did with great fruit unto his neighbours and comfort to himself. This gentleman therefore they adjoined to their company, as they had done Mr. Rookewood, giving to them both the oath of secrecy, according to their custom.

Then they called in one Mr. Robert Keyes, a grave and sober man, and of great wit and sufficiency, as I have heard divers say, that were well acquainted with him. His virtue and valour were the chiefest things wherein they could expect assistance from him ; for otherwise, his means were not great, but in those two, by report, he had great measure. More was the pity that such men, so worthy to be esteemed, should lose themselves in such a labyrinth of erring courses.

But of all others, he that was most pitied and generally most commended of all men, was the next whom Mr. Catesby thought fit to acquaint with the matter, therein to have his help and assistance in all kinds, both for counsel and forces and provision of money, of horses and armour and men and followers ; in all which, put them all together and there was not such a man amongst them. And this was Sir Everard Digby, a Knight of great living and great account in his country. He was of an ancient and great family, whose ancestors were a great help to the suppressing of Richard III. the tyrant, and the bringing and setting up of King Henry VII. from whom our King James is lineally descended : whereupon King Henry did make Knights in the field seven brothers of his house at one time, from whom descended divers houses of that name, which live all in good reputation in their several countries. But this Sir Everard Digby was the heir of the eldest and chiefest house, and one of the chiefest men in Rutlandshire where he dwelt, as his ancestors had done before him, though he had also much living in Leicestershire and other shires adjoining. His estate was not fully come into his hands, for his mother lived, who had above seven or eight hundred pounds a year ; but he had in his hands above 2,000 marks a year. This gentleman was always Catholicly affected, and heir unto the piety of his parents, as well as to their living : for they were ever the most noted and known Catholics in that country. And although this gentleman being left a ward by his Father's untimely death, was not brought up Catholicly in his youth, but at the University by his guardians, as other young gentlemen use to be ; yet when he came to be of riper years, and had the guiding of himself and his own estate, he affected most the company of Catholics and finding by them the necessity not only of believing but of practising also and professing that religion, he presently made election rather to suffer with Catholic religion, and to bear with Catholics the cross of persecution than to rise with heresy and to be advanced in the Court, which until then he had followed, and was as likely to be raised as any there, if he would have followed the time. For indeed to do him right, he was as complete a man in all things that deserved estimation or might win affection, as one should see in a kingdom. He was of stature about two yards high, very little lower than Mr. Catesby but of stronger making ; of countenance so comely and manlike, that when he was taken and brought up to the Court (not in the best case to make show of himself as you may imagine), yet some of the chiefest in the Court seeing him out of a window brought in that manner, lamented him much, and said he was the goodliest man in the whole Court. He was skilful in all things that belonged unto a gentleman, very cunning at his weapon, much practised and expert in riding of great horses, of which he kept divers in his stable continually with a skilful rider for them. For other sports of hunting or hawking, which gentlemen in England so much use and delight in, he had the best of both kinds in the country round about, insomuch that he made that the colour of his going into Warwickshire at this time, and of drawing company together of his friends, as it were to a match of hunting which he had made. For all manner of games which are also usual for gentlemen in foul weather, when they are forced to keep house, he was not only able therein to keep company with the best ; but was so cunning in them all, that those who knew him well, had rather take his part than be against him. He was a good musician and kept divers good musicians in his house ; and himself also could play well of divers instruments. But those who were well acquainted with him do affirm that in gifts of mind he excelled much more than in his natural parts ; although in those also it were hard to find so many in one man in such a measure. But of wisdom he had an extraordinary talent, such a judicial wit and so well able to discern and discourse of any matter, as truly I have heard many say they have not seen the like of a young man, and that his carriage and manner of discourse were more like to a grave Councillor of State, than to a gallant of the Court as he was, and a man but of twenty-six years old (which I think was his age or thereabouts). And though his behaviour were courteous to all, and offensive to none, yet was he a man of great courage and of noted valour, which at his end he showed plainly to the world, all men seeing and affirming that he made no account at all of death. He was so studious a follower of virtue, after he became Catholic, that he gave great comfort to those that had the guiding of his soul (as I have heard them seriously affirm more than once or twice), he used his prayers daily both mental and vocal, and daily and diligent examination of his conscience : the Sacraments he frequented devoutly every week, and to that end kept a Priest in his house continually, who for virtue and learning hath not many his betters in England. Briefly I have heard it reported of this Knight by those that knew him well, and that were often in his company, that they did note in him a special care of avoiding all occasions of sin and of furthering acts of virtue in what he could ; to which end he was not only studious to bring as many to be Catholics as he could (studying books of purpose to enable himself in that kind), and brought in divers of that sort and some of great account and place. Not only in this highest kind, wherein he took very great joy and comfort, but also in ordinary talk, when he had observed that the speech did tend to any evil, as detraction or other kind of evil words which sometimes will happen in company, his custom was presently to take some occasion to alter the talk, and cunningly to bring in some other good matter or profitable subject to talk of. And this, when the matter was not very grossly evil, or spoken to the dishonour of God or disgrace of His servants ; for then, his zeal and courage- were such, that he could not bear it, but would publicly and stoutly contradict it, whereof I could give divers instances worth relating, but am loth to hold the reader longer; having written thus much of him, that it may appear what was the cause why he was so much and so generally lamented, and is so much esteemed and praised by all sorts in England, both Catholics and others, although neither side do or can approve this last outrageous and exorbitant attempt against our King and country, wherein a man otherwise so worthy, was so unworthily lost and cast away to the great grief of all that knew him and especially of all that loved him. And truly it was hard to do the one and not the other.

The last of all that Was Called to be partaker in this treacherous plot was Mr. Francis Tresham, a gentleman of Northamptonshire of great estate, esteemed then worth 3,ooo/. a year. His parents had been long time Catholic and his father often in prison for his conscience, although he paid the statute duly besides of 2O/. a month for his refusing to go to Church with heretics. This gentleman had been wild in his youth, and even till his end was not known to be of so good example as the rest, though, towards his later years, much reclaimed and good hope conceived ofhim by divers of good judgment. I think Mr. Catesby (who was his near kinsman) did chiefly acquaint him with the matter in regard of his help by provision of money which Mr. Tresham was as well able to do as the best, and thought to be as likely to be both faithful and forward as any, having been, before, a companion with them in that action of the Earl of Essex in Queen Elizabeth's time, and both then and since, continually discontented with the proceedings of the State. But it is thought by most, that Mr. Tresham had not that zeal for the advancement of the Catholics' cause in respect of itself, as the others had. And it seems by Mr. Winter's confession, they also repented afterwards that they had made him of their council, fearing him to be the man who had opened the matter and so defeated them of their purpose ; whereof I must treat in the next chapter.

But these gentlemen being thus added to the number of the conspirators, they then began to conclude amongst themselves how everything should be acted, as saith Mr. Winter. They designed Mr. Faulkes to be the man that should strike that first and fatal stroke and attend upon the powder ready prepared in the cellar, to set it on fire with a match, when the hour appointed should be come, which should be the first day of the Parliament, because then the King would certainly be there, and all the Lords also (but those whom they meant to keep from thence by some means or other), likewise all their Bishops and most of the chiefest Puritans of the land.

Mr. Percy his office should be (with a certain company ready to assist him) presently after that first blow to enter the place where the young Prince or the Duke Charles were kept, to seize upon his person, who being safely placed in the custody of Catholics, presently they would have proclaimed him King. Sir Everard Digby was in Warwickshire at the time appointed, as it was agreed amongst them, where, under pretence of a hunting match (having brought his hawks and hounds to Dunsmore Heath for the purpose, and hunted there two or three days before), he gathered many of his friends together, and had himself great store of men, and many fair and goodly horses. He had also made great provision of armour and shot, which he sent before him in a cart with some trusty servants, and had made ready above i,ooo/. in ready coin, as his servants since have averred that did escape, and one of them delivered up great part of the money to the King's officers so soon as he saw his master fallen into the lapse.

Their intention was that if they failed of the Prince or Duke about London, which was not unlike they should, then would some of them hasten down to Sir Everard Digby after the blow were given, others stopping the ways that no news might pass but by their permission ; and then should Sir Everard Digby have made sure, with his forces and friends, to have taken the Lady Elizabeth out of the Lord Harrington his hands, whom then they would presently have proclaimed heir-apparent to the Crown. Then had they (as is expressed in their confessions) a proclamation ready penned, wherein they would have commanded all sorts of men, by authority of the Prince or Princess, who would have been in their custody, to assist the quiet settling of the young King or Queen in their seat. They would have offered freedom from all taxes and impositions, and payments of subsidies, and such like ; and for religion, they would have left it as yet free for all sorts to follow their own conscience without compulsion, which afterwards they meant (saith the printed confession) to have set better in order. And so indeed the Catholics are able to perform it, if they might have freedom, by many means more effectual than force of arms, in such an unsettled State as that must needs have been for a time ; and by many means more effectual than heretics have, who therefore only use the sword. For, if the truth might freely be preached, if the lives and examples of Catholics, and especially of Religious Orders, might be seen and suffered in public, if those that be followers of the Apostles, and expert in their trade of fishing for men, might be freely permitted to use and show their skill in gaining of souls, no doubt then but the sun shining so bright, as it would be seen to do in the doctrine of Truth, would disperse the clouds of error ; no doubt but the candle set upon the candlestick \vould give light unto many minds that now are groping in the Egyptian darkness of heresy. And no question but many and great fishes would be taken, Avhen the night being past, our Lord would both license and direct His servants to cast their net on the right hand, and that such a net as would not break, the net of Peter that is entire and undivided, although it be able to catch at one draught a hundred, fifty and three great fishes, wherein is designed by a great and certain number an uncertain and not to be numbered gain of souls, that the Apostles and Apostolic men should gain to Christ. And this these gentlemen hoped had been the time. But God, in Whose only hands and disposition are the moments of time, and Who hath placed bounds and limits unto the sea, and saith unto it, "Usque hue venies et non procedes amplius et hie confringes tumentes fluctus tuos : "He Who is the Master must be also the Measurer of time, and He will not easily make men of His council when their afflictions shall end and how far they shall proceed ; especially such men as themselves will not follow counsel, but run headlong upon such a course as this, which no wise man could or would have counselled. No, on the contrary side, that was verified in this practice which Christ foretold unto St. Peter, when upon zeal he drew his sword in defence of his Master, Matt. 26. " Omnes qui acceperint gladium, gladio peribunt," said our Lord, forewarning all men, that howsoever they may receive the sword or use it, when it is given them by authority (as it is to all lawful governors and officers in commonwealths), yet to take the sword (which noteth a private will or power not authorized) is not without a fault, nor shall be without a fall. And so it happened to these conspirators, as the sequent chapter will declare.

The following chapters of Father Gerard's A Narrative of the Gunpowder Plot are omitted:

CHAPTER VII.

HOW, THE PARLIAMENT DRAWING NEAR, THE WHOLE

PLOT WAS DISCOVERED, AND THAT WHICH ENSUED

THEREUPON.

CHAPTER VIII.

HOW UPON EXAMINATION OF THE PRISONERS IT WAS

APPARENT THAT NO OTHER CATHOLICS COULD BE

TOUCHED WITH THE CONSPIRACY. THE SAME ALSO

CONFIRMED BY HIS MAJESTY'S OWN WORDS, TO THE

GREAT COMFORT OF CATHOLICS.

CHAPTER IX.

HOW THE FATHERS OF THE SOCIETY WERE BY INDUSTRY

OF THE HERETICS DRAWN INTO THIS MATTER, TO

INCENSE THE KING AGAINST THEM, AND FOR THEM

AGAINST THE CATHOLIC RELIGION.

CHAPTER X.

HOW FATHER GARNETT, THE SUPERIOR, WAS DIS-

COVERED AND TAKEN IN W^ORCESTERSHIRE AND

BROUGHT UP TO LONDON: AND OF HIS FIRST

ENTREATY AND EXAMINATION.

CHAPTER XL

OF FATHER GARNETT, HIS CARRIAGE TO THE TOWER

AND SUBTLE USAGE THERE. ALSO OF THE USAGE

OF FR. OULDCORNE AND NICHOLAS OWEN, RALPH,

AND JOHN GRISOLL IN THE SAME PLACE.

CHAPTER XII.

OF THE ARRAIGNMENT, CONDEMNATION, AND EXECUTION

OF THE CONSPIRATORS, WITH THE FULL CLEARING

OF SOME OF THE SOCIETY FALSELY ACCUSED IN

THIS ARRAIGNMENT.

CHAPTER XIIL

OF THE ARRAIGNMENT AND CONDEMNATION OF

FATHER GARNETT.

CHAPTER XIV.

OF THE ARRAIGNMENT AND EXECUTION OF FATHER

OULDCORNE AND THOSE THAT SUFFERED WITH HIM,

AND OF THE OCCURRENCES THERE, WITH A BRIEF

RELATION OF HIS LIFE.

CHAPTER XV.

OF THE EXECUTION OF FATHER GARNETT, WITH A

BRIEF RELATION OF HIS LIFE,

CHAPTER XVI.

OF THE STATE OF CATHOLICS AFTER FATHER GARNETT

HIS EXECUTION : HOW GOD DID COMFORT THEM

WITH SOME MIRACULOUS EVENTS, AND HOW THEIR

ZEAL INCREASED, NOTWITHSTANDING THE INCREASE

OF PERSECUTION.

CHAPTER XVII.

A CATALOGUE OF THE LAWS AGAINST CATHOLICS MADE

BY QUEEN ELIZABETH AND CONFIRMED BY THIS

KING, AND OF OTHERS ADDED BY HIMSELF.