Sir Everard Digby's letter to Robert Cecil, Earl of Salisbury [probably written between May and September, 1605]

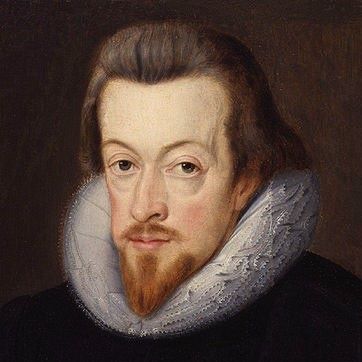

Robert Cecil, 1st Earl of Salisbury and confidant of King James I

Note: In this letter, Digsby offers to help find a priest to send to Rome to meet with the Pope and try to secure from the Pope a promise not to excommunicate King James. Digsby suggests that this might ease tensions between authorities and Catholics in England. He suggests it could both securing safety for the King from various Catholic intrigues [including the Gunpowder Plot?] and, for Catholics, ease restrictions ton the practicing of their religion. Digby also notes that English Catholics had an expectation, based on perceived promises from James, that their persecution would end under James’ reign—but, at the time of this letter, are seeing those hopes dashed.

Right Honourable, I have better reflected on your late speeches than at the present I could do, both for the small stay which I made, and for my indisposition that day, not being very well, and though perhaps your Lordship may judge me peremptory in meddling, and idle in propounding, yet the desire I have to establish the King in safety will not suffer me to be silent.

One part of your Lordship's speech (as I remember) was that the King could not get so much from the Pope (even then when his Majesty had done nothing against Catholics) as a promise that he would not excommunicate him, so long as that mild course was continued, wherefore it gave occasion to suspect, that if Catholics were suffered to increase, the Pope might afterwards proceed to excommunication, if the King would not change his religion. But to take away that doubt, I do assure myself that his Holiness may be drawn to manifest so contrary a disposition of excommunicating the King, that he will proceed with the same course against all such as shall go about to disturb the King's quiet and happy reign; and the willingness of Catholics, especially of priests and Jesuits, is such as I dare undertake to procure any priest in England (though it were the Superior of the Jesuits) to go himself to Rome to negotiate this business, and that both he and all other religious men (till the Pope's pleasure be known) shall take any spiritual course to stop the effect that may proceed from any discontented or despairing Catholic.

And I doubt not but his return would bring both assurance that such course should not be taken with the King, and that it should be performed against any that should seek to disturb him for religion. If this were done, there could then be no cause to fear any Catholic, and this may be done only with those proceedings (which as I understood your lordship) should be used. If your Lordship apprehend it to be worth the doing, I shall be glad to be the instrument, for no hope to put off from myself any punishment, but only that I wish safety to the King and ease to Catholics. If your Lordship and the State think it fit to deal severely with Catholics, within brief there will be massacres, rebellions, and desperate attempts against the King and State. For it is a general received reason amongst Catholics, that there is not that expecting and suffering course now to be run that was in the Queen's time, who was the last of her line, and last in expectance to run violent courses against Catholics; for then it was hoped that the King that now is would have been at least free from persecuting, as his promise was before his coming into this realm, and as divers his promises have been since his coming, saying that he would take no soul money nor blood. Also, as it appeared, was the whole body of the Council's pleasure, when they sent for divers of the better sort of Catholics (as Sir Thos. Tressam and others) and told them it was the King's pleasure to forgive the payment of Catholics, so long as they should carry themselves dutifully and well. All these promises every man sees broken, and to thrust them further in despair, most Catholics take note of a vehement book written by Mr. Attorney, whose drift (as I have heard) is to prove that the only being a Catholic is to be a traitor, which book coming forth, after the breach of so many promises, and before the ending of such a violent parliament, can work no less effect in men's minds than a belief that every Catholic will be brought within that compass before the King and State have done with them. And I know, as the priest himself told me, that if he had not hindered there had somewhat been attempted, before our offence, to give ease to Catholics. But being so safely prevented, and so necessary to avoid, I doubt not but your Lordship and the rest of the Lords will think of a more mild and undoubted safe course, in which I will undertake the performance of what I have promised and as much as can be expected, and when I have done, I shall be as willing to die as I am ready to offer my service, and expect not nor desire favour for it, either before the doing it, nor in the doing it, nor after it is done, but refer myself to the resolved course for me. So, leaving to trouble your Lordship any further, I humbly take my leave. Your Lordship's poor bedesman, Ev. Digby.

Addressed "To the Right Honourable the Earl of Salisburie give these."

Sealed.

[P.R.O. Dom. James I. xvii. 10.]