The Gunpowder Plot Treason Trials (1606): An Account

By Douglas O. Linder (2024)

Please to remember the Fifth of November

Gunpowder Treason and Plot.

We know no reason why Gunpowder Treason

Should ever be forgot.

—Translation of “In Quintum Novembris” (“On the Fifth of November”) by John Milton (1626).

Few trials have better stood the test of time than the Gunpowder Plot treason trials of 1606. Even today, bonfires are lighted in celebration all across England on November 5, Guy Fawkes Day, the day on which in 1605 one of the Gunpowder plotters, Guy Fawkes, was discovered lurking in the cellar below Westminster Palace, where he intended the next morning to light a large stockpile of gunpowder—when King James, Queen Anne, and Prince Henry would all be attending the long-delayed opening session of Parliament.

The Gunpowder Plot, and the trials that followed, can only be understood in the context of the time. A time when English Catholics faced cruel persecution from Protestant authorities. A time when Catholic hopes for outside intervention from Spain or other Catholic nations were dashed. A time when a band of Catholic extremists might decide that blowing about Parliament, and the King along with it, was worth the risk.

Background: A Religiously-Divided Nation

Before the 16th century, England was, like other European nations, a Roman Catholic country. Any citizen who publicly questioned the teachings of the Catholic Church was deemed a heretic and subject to punishment.

Martin Luther and the Reformation, with its origins in 1517 in Germany, challenged some of the practices of the Catholic Church and the Protestant movement rapidly gained adherents, primarily across norther Europe. England’s break with Rome came in 1534 when King Henry VIII, incensed that the Pope refused to grant him an annulment from the marriage to his first wife, Catherine of Aragon, thus allowing him to marry the object of his infatuation, Ann Bolelyn, declared himself the Supreme Head of the Church of England. King Henry VIII closed England’s monasteries and stripped them of their lands and assets. Henry’s son, King Edward VI, continued to push Protestant reforms during his short six-year reign from 1547 to 1553.

With Edward’s death, his sister Mary, a staunch Roman Catholic, became Queen. Queen Mary attempted to reverse the Reformation in England. During her rule, Protestants faced persecution and outspoken Protestant figures, from churchmen to ordinary citizens, faced punishments ranging from imprisonment to being burned at the stake.

When Queen Mary died at age 42 in 1558, England again lurched back toward Protestantism and persecution under the rule of Queen Elizabeth I. Attendance at Protestant churches became mandatory and Catholics wishing to practice their religion were again forced underground.

Religious tension and persecution of Catholics in England heated up following a failed 1569 plot to assassinate Queen Elizabeth and replace her with her cousin, the Catholic Mary Queen of Scots. Tensions rose further the following year when Pope Pius V excommunicated Elizabeth and absolved all her subjects from allegiance to her. The Pope’s action had the unsurprising effect of convincing Elizabeth to stiffen penalties and clamp down more forcefully on English Catholics. Internationally, Catholic Spain and England were in constant conflict and on the Continent, Protestant English were horrified by reports of Catholics atrocities, including massacres of Protestants in France and Antwerp. English Catholics came to be viewed as a serious national security threat – an ‘enemy within.’ Priests and lay Catholics soon filled every prison in the country.

It was a crime for priest to say Mass. Catholics were prohibited from baptizing their children in the Catholic faith or sending them abroad to a Catholic country. Every Catholic was required to attend a Protestant church on Sundays. All office holders and clergy had to swear allegiance to the sovereign as head of the Church. Priests were charged with treason and drawn and quartered.

English Catholics during the late 1500s were divided. Some saw their religious beliefs as a private matter, practiced their religion discreetly in their own home, and urged loyalty to the Crown. Other Catholics, called “recusants,” considered the situation intolerable and some among them advocated direct action, including violence if necessary, to restore the right to practice their religion more openly.

In March of 1603, Queen Elizabeth, in her seventieth year and childless and without consort, was depressed, weak, and dying. The Councilors of State gathered at Richmond Palace to make a momentous decision. They would decide who would be the next ruler of England. The Councilors chose as Elizabeth’s successor King James of Scotland, whose grandmother was a Tudor princess. When death came to the Queen on the morning of March 24, the Councilors drafted a document proclaiming James King of England.

The choice of James to be the new king was welcomed by English Catholics, hopeful that the Catholicism of James’ mother, Mary Queen of Scots’, would lead King James to lift the heavy penalties imposed on Catholics during the reign of Elizabeth. They also took hope from the fact that James’ wife, Queen Anne, was a privately practicing Catholic. Some even allowed themselves to imagine that James himself might convert to Catholicism. Adding to Catholic hopes, Pope Clement VIII extended his good wishes toward the new king. In April, Father Henry Garnet, the Jesuit Superior of England, called it “a golden time,” one of “unexpected freedom” and for “great hope” of “toleration” from English authorities.

But Catholics in England were disappointed. There was a large gap between their hopes and reality. King James never had any intention of becoming Catholic. In a letter, James wrote that he had no trouble with his subjects having “a diversity of opinions about religion,” but added, “I should be sorry that Catholics should so multiply that they might be able to practice their old principles on us.” And, it turned out, in the early period of James’ reign his relatively lenient policies did have the effect, according to a finding by Parliament in 1606, of multiplying the number of priests in England from one hundred to one thousand.

One year after his coronation, King James began to take a harsher line against Catholics. In 1604, he declared his “utter detestation” of Catholicism and all of its “superstitions.” James confirmed most of the harsh anti-Catholic laws of the previous reign. In April 1604, a bill was introduced in Parliament that would declare all Catholics to be outlaws. The next month, a group of Catholic fanatics began plotting.

The Gunpowder Plot

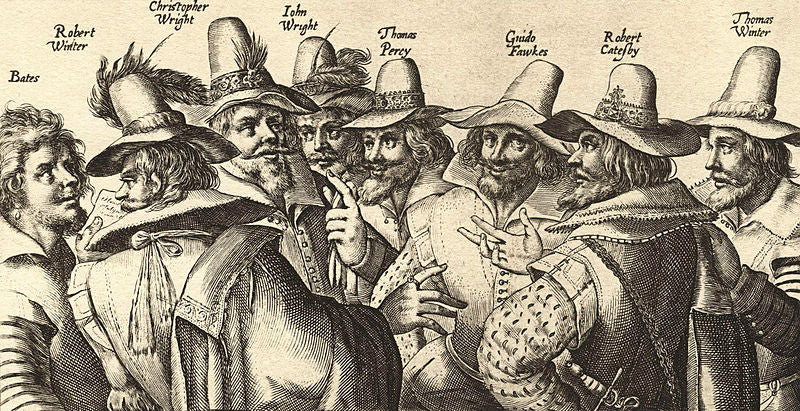

The origins of the Gunpowder Plot can be traced to a meeting at a London inn called the Duck and Drake on Sunday, May 20, 1604. Five conspirators attended, but their number would eventually grow to thirteen. The prime mover was Robert (“Robin”) Catesby, a handsome, charismatic young man, loved by friends and family alike. He had a passion for theology and considered himself a man of action. The other original conspirators included Robin’s cousin, Tom Wintour, Jack Wright and his brother-in-law Thomas Percy, and the man who history would make the face of the Gunpowder Plot, Guido (“Guy”) Fawkes.

Catesby proposed an audacious and horrific plan. He proposed to blow up the Parliament House, killing King James and the entire government. The explosion, it was decided, would take place on the opening session of the next Parliament, then set for February 1605, when the King and Queen would be in attendance. Later, owing to rising fears the plague in London, the opening would be postponed until the fall of 1605.

The plot was terrorism, plain and simple, but neither the term “terrorist” or “terrorism” was in use in the 1600s. Catesby argued it was necessary to “strike at the root” and the Parliament and the King were responsible for their intolerable persecution. Tom Wintour had initially opposed the idea, pointing out that if the plot failed, they and all English Catholics would have hell to pay. But Catesby insisted that the “strong remedy” was necessary and eventually Wintour came on board.

The five plotters swore an oath of secrecy upon a prayer book and then walked to another room in the inn, where Father John Gerard celebrated mass. (Given the timing of the Mass, authorities would later claim Father Gerard must have had knowledge of the conspiracy, but little evidence supports this.) Later, the conspirators ordered special swords with the inscription “The Passion of Christ.” They considered themselves holy warriors.

Additional conspirators were added over the following months, with most coming from the recusant territory in the English midlands near Stratford-upon-Avon. This was convenient, because as the plot evolved it included kidnapping nine-year-old Princess Elizabeth and installing her as a puppet Queen friendly to Catholics, after her father and mother and brother Prince Charles were, if the plot went as planned, all killed on the opening day of the next Parliament. Princess Elizabeth lived under guardianship in the midlands.

Princess Elizabeth

Robert Keyes joined the plot in October, then Catesby’s servant, Thomas Bates, two months later. In March of 1605, Robert Wintour, John Grant, and Kit Wright were added. In autumn, a final three conspirators were recruited. First among them was the wealthy and well-connected Rockwood Ambrose, owner of a large stable of horses, useful for an escape. Francis Tresham, who would later offer a highly partial account of the Gunpowder Plot, became the twelfth conspirator. The last conspirator to be added was Edward Digby, entrusted by the group with the task of abducting Princess Elizabeth.

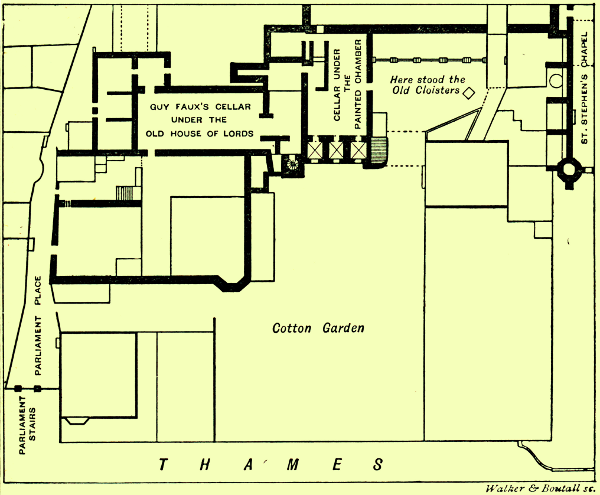

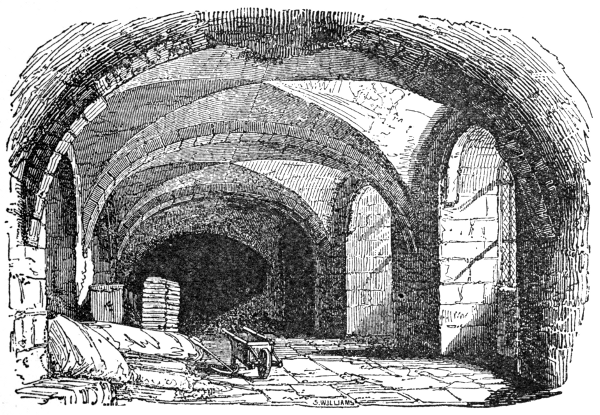

That same month, the plotters leased a so-called cellar (actually the space was on ground level) directly below the House of Lords. The space was likely, in medieval times, a great kitchen for the ancient Palace of Westminster. Over the next few months, the conspirators transported a large quantity of gunpowder to the cellar—a quantity sufficient to blow up the House of Lords above it. Conveniently for the plotters, there was a glut of gunpowder in 1605 and the material was easily and cheaply purchased. Guy Fawkes, who was chosen to ignite the gunpowder at the appropriate time, took up lodging in a small apartment in the cellar.

In June 1605, in a room on Thames Street in London, Robin Catesby asked Jesuit leader Father Garnet about the morality of “killing innocents.” Garnet was later to claim he interpreted the question as an innocent one and did not suspect that Catesby was planning an explosion that would result in the death of innocent people. But authorities would see it otherwise. Garnet told Catesby that in some circumstances, such as ending a siege in wartime, it might be moral to take actions that would mean the loss of innocent lives.

The next month, Father Garnet was approached by Father Tesimond in the same Thames Street room Tesimond was distressed. He had just taken Robin Catesby’s confessional and was horrified to hear of his plans for the opening of Parliament. But information learned in a confession is under a sacred seal. As much as Tesimond wanted to do something to head off what would likely be a disaster for all concerned, he felt that his religious duty to protect the seal of the confession prevented him from doing anything. Father Garnet, who now did know of the plot, said later: “I would to God that I had never heard of the Powder Treason.” Garnet spoke to Catesby, urging him to not to run “headlong into mischief.” He thought he had headed off calamity, but he was wrong.

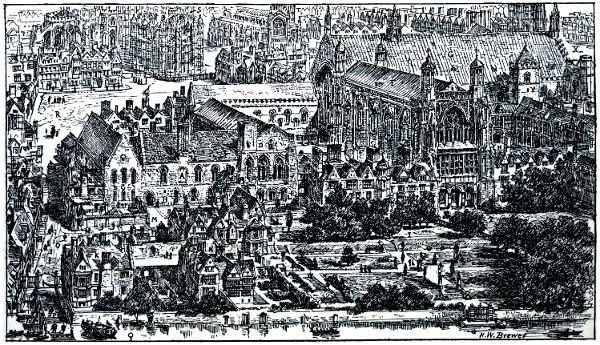

Westminster in the early 1600s

On July 28, a proclamation from Parliament set the date of November 5, 1605 for the next meeting of Parliament. Life in England seemed normal. The King headed to the country to pursue his passion of hunting. William Shakespeare worked in Oxford on his new play, Macbeth. Father Garnet and a band of thirty other Catholics left on a pilgrimage to the shrine of St. Winifred, with its well of healing waters, along the coast of Wales, staying in safe-houses along the way. In late August, Guy Fawkes (using the alias John Johnson) discovered that the gunpowder stored in the cellar had decayed to near the point of uselessness and would have to be replaced.

In October, a series of meetings resulted in a final plan for the fateful day of November 5. Guy Fawkes would light the fuse in the cellar and then quickly escape the scene by boat across the Thames. In the midlands, news of the explosion would cause a rising of Catholics. Princess Elizabeth would become the puppet Queen. On the continent, Guy Fawkes would explain the need for the desperate action to Catholic powers, including Queen Isabella in Spain.

The Plot is Discovered and Frustrated

But on October 26 a letter undid all of the planning. The letter was delivered at night in a street to a servant of Lord Monteagle, a Catholic-sympathizing member of the House of Lords. Who authored the letter is still a question for debate. The stranger who delivered the letter was described as “a man of reasonable tall personage.” The letter said:

My lord, out of the love I beare to some of youere frends, I have a care of youre preservacion, therefore I would aduyse you as you tender your life to devise some excuse to shift youer attendance at this parliament, for God and man hath concurred to punishe the wickedness of this tyme, and thinke not slightly of this advertisement, but retire yourself into your country, where you may expect the event in safety, for though there be no apparance of anni stir, yet I saye they shall receive a terrible blow this parliament and yet they shall not seie who hurts them this cowncel is not to be contemned because it may do yowe good and can do yowe no harme for the dangere is passed as soon as yowe have burnt the letter and i hope God will give yowe the grace to mak good use of it to whose holy proteccion i comend yowe.

Lord Monteagle (William Parker)

Monteagle decided to take the letter that same night to Robert Cecil Salisbury, a member of the King’s Privy Council. Salisbury, in turn, informed other Council members of the letter’s contents. The King, meanwhile, was off on yet another hunting expedition and could not immediately be reached. Just as well, Salisbury, believed, as there was advantage in allowing the plot to ripen.

It is hard to know what to make of the letter. Should the anonymous letter be taken at face value as a letter by a well-wisher hoping to spare Monteagle’s life? Or was it, as most historians now believe, a letter Monteagle himself caused to be written so as to disassociate himself from the plot (his brother-in-law, Francis Tresham was one of the plotters) and become the nation’s hero? Most likely, Salisbury, who had already heard some “stir” about a treason plot, knew the letter was a fake, but saw good reason to allow Monteagle to become the hero of the story.

Rumors of the plot’s discovery reached Robin Catesby. but he stubbornly refused to call off the planned explosion. Meanwhile, the key conspirators in London knew nothing of the discovery. On October 30, Guy Fawkes made a final inspection of the gunpowder in the cellar.

On November 1, Salisbury presented the Monteagle letter to King James, recently returned from his hunting. The King read the letter twice. He interpreted it as it was, a plan to blow up Parliament.

On the day and the night before the scheduled opening session of Parliament, two searches were conducted, “both above and below.” In the first search, Lord Suffolk noticed a huge amount of firewood heaped in the cellar, far more than would seem necessary to warm a small lodging. Suffolk also learned that the cellar’s tenant was Thomas Percy, known to Salisbury as a “backward” Catholic.

The second search, around midnight, was headed by Thomas Knevett, a Privy Chamber member. It was then in the cellar that Knevett spotted a tall man in a cloak and dark hat lurking in the shadows. He was apprehended and bound. He gave his name as John Johnson. He claimed to be a servant of Thomas Percy. But he was, of course, Guy Fawkes.

Lantern carried by Guy Fawkes on the night of his arrest

Word of Fawkes’ arrest sent panicked conspirators in London scurrying out of London on horseback. Kit Wright, Thomas Percy, Robert Keyes, and Ambrose Rockwood all rode north, with Rockwood, the best horseman on the fastest horse, being the first to reach Robin Catesby and inform him of the plot’s failure. Catesby, however, refused to give up hope, believing that an armed Catholic uprising still was possible.

Meanwhile, in London the government closed all ports. Parliament met briefly in the afternoon and postponed its opening session until March. A journal entry for the session contained news of the plot and its discovery:

This last night the Upper House of Parliament was searched by Sir Tho. Knevett; and one Johnson, servant to Mr Thomas Percye, was there apprehended; who had placed 36 barrels of gunpowder in the vault under the House, with a purpose to blow King and the whole Company, when they should there assemble. Afterwards divers other gentlemen were discovered to be of the Plot.

Guy Fawkes was questioned by authorities, including King James. When the King asked “Johnson” how he could “compose so hideous a treason,” Fawkes replied that a dangerous disease required a desperate remedy.

Fawkes being interrogated by King James and his Council in the King's bechamber at Whitehall

Tortures and Trials

On November 6, King James decided to apply torture to the man known then as “John Johnson.” The King’s letter authorizing torture said that “Johnson” did not otherwise confess, he should be subject first to “the gentler tortures.” and then, if necessary to the worst—the gentler tortures being manacles, and the worst the rack. That same day, Lord Chief Justice Sir John Popham, leading the investigation of the plot, had learned enough about the conspiracy (probably from Francis Tresham) to have identified eight suspect conspirators.

Guy Fawkes continued not to reveal his real identity, probably hoping to gain time for his fellow conspirators to make their escapes. He was taken to the Tower of London, which housed the only rack in England. By late on November 7, Fawkes was broken and began to talk.

On November 8, when in London Fawkes was signing the first of his two written confessions, the High Sheriff of Worcestershire, Sir Richard Walsh, along with his force of 200 men, were closing in on a band of conspirators, including Catesby, Percy, Rockwood, Grant, Morgan, Bates, Wright, and Wintour, in their Holbeach house. Soon after the siege of the house began, Tom Wintour was shot in the shoulder running across a courtyard. The next shots hit Jack and Kit Wright. Then Rockwood took a shot. Catesby and Percy stood by the door to make a last stand. They were both taken down by a single shot. (The last of the conspirators captured was Robert Wintour, on January 9.)

Percy and the Wright brothers were mortally wounded. Catesby lived long enough to crawl though the house and grab a picture of the Virgin Mary—he died with the picture clutched in his arms. Catesby wish not to be taken alive was fulfilled. But Rockwood, Wintour, Grant, and Morgan were captured and taken first to Worcester, then to the Tower of London. Over the next ten weeks, the captured conspirators would be tortured and interrogated, though only one of the resulting confessions—that of Thomas Wintour—was ever published. Wintour’s confession is notable because it is the only confession from one of the original conspirators, though it is suspected that it might actually have been dictated by his interrogators, not Wintour himself, given that his signature is misspelled as “Winter.”

Unfortunately for the Jesuit community in England, one of the other conspirators, Thomas Bates, directly implicated a priest, Father Tesimond, a false implication Bates would later apologize for, and probably was made after beatings and a promise of a pardon. But the Bates confession gave authorities what they wanted—an excuse to launch a criminal investigation of Jesuit leaders.

On November 9, King James spoke to Parliament about the plot and its recent discovery. In his speech, he recognized that the conspirators were fanatics and he understood that not “all professing the Romish religion were guilty of the same.” Later, however, he would adopt a more vengeful approach to Catholics.

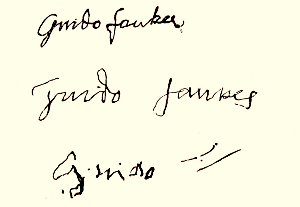

Guy Fawkes’ last confession was attested to in front of Commissioners on November 10. It was made only after prolonged rounds of torture, almost certainly including the rack. His signature tells a tale. It was little more than a scrawl, made with pathetic jabs of a pen.

Signatures of Guido (Guy) Fawkes (top: normal, middle: after first round of torture, bottom: after being racked

The trial of eight surviving conspirators for high treason began on January 27, 1606 in Westminster Hall. Seven of the eight were carried to Whitehall from the Tower of London by barge. Although called a trial, it was really a show trial, the outcome of the proceeding was a foregone conclusion. The defendants had no counsel or any number of other protections granted to modern-day defendants.

The prisoners were led into the hall and displayed on a scaffold. King James watched from a room where he could see without being seen. Queen Anne and young Prince Henry observed the proceedings from another secluded spot. Many members of Parliament were also in attendance. Presiding over the trial was Sir John Popham as Lord Chief Justice. Eight Lords Commissioners also sat in trial.

After the reading of the indictment, seven of the eight men plead “Not Guilty.” Everard Digby plead “Guilty,” entitling him to a separate trial. Following the pleas, the Sergeant-at-Law read a “declaration” that called the alleged treason the most horrific plot “the ear of man ever heard or the heart of man ever conceived.” Then the prosecutor, Attorney-General Sir Edward Coke delivered a speech which including references to past Catholic plots against the government, complements to Lord Monteagle for his role in discovering the plot, and complaints about the practice by English Catholics of “equivocation” (misleading representations concerning their compliance with state laws).

Coke proceeded to spell out the grisly punishment that undoubtedly awaited the traitors: each would be dragged to his execution on the ground by a horse. Each would have their private parts cut off and burned in front of them. Their bowels, hearts and heads would be cut out or hacked off. When all that was over, their bodies were to be displayed in the open so that they might become “prey for the fowls of the air.”

After Coke finished his lengthy address, confessions and records of examinations were read, including the specific confessions of Guy Fawkes and Robert Wintour. The last evidence introduced came from a spy installed at the Tower of London, reporting on alleged overheard conversation between Robert Wintour and Guy Fawkes.

After the prosecution evidence, each of the conspirators was allowed to speak. Some merely asked for mercy or expressed remorse for bringing a fellow conspirator into the plot. Ambrose Lockwood spoke longest, attributing his involvement in the plot to his feelings for Catesby, whom he “loved above any worldly man.”

Following the separate, summary trial for Digby, the Sergeant-at-Law asked for the judgment of the court. The Lord Chief Justice then made a short statement before directing the jury to consider its verdict. Guilty, each and every one. As the Lord Chief Justice pronounced judgement, Digby cried out, “If I may but hear any of your lordships say, you forgive me, I shall go more cheerfully to the gallows.” The lords responded: “God forgive you, and we do.”

Epilogue

On January 30th and 31st, the eight condemned conspirators were executed, four to a day. Each man was conveyed to the site of their death through the public streets strapped to a wooden sledge. The first set of hangings took place in St. Pauls’ churchyard, the second set at Old Palace Yard at Westminster. The last plotter to mount the scaffold at Westminster was Guy Fawkes, so weak from his torture that the hangman had to help him mount the ladder to the hanging rope.

Authorities, anxious to send a message, decided to prosecute a number of priests for their alleged connection to the plot, included Father Garnet, Father Gerard, Father Tesimond, and Father Oldcorne. Coke wanted to show that Catholics were not persecuted merely for their religious beliefs, but rather for their treasonable practices. This despite the fact that none of the priests charged were either part of the plot or endorsed it. In fact, to one degree or another, each of the priests had tried to discourage the treason.

Edward Coke suggested that Father Henry Garnet’s offense was that he prayed for the success of the plot, though Garnet’s prayer was actually for an end to Catholic persecution. While in fact neither Garnet nor any other priest was guilty of treason, English law also made it a crime to know of a treasonous plot and not report it to authorities, a crime called “misprision of treason.” (For his part, Garnet might have been inclined to notify authorities, but felt the seal of the confessional prevented him from doing so.)

Father Garnet faced trial for high treason and misprision of treason at Guidhall on March 28, with King James once again in attendance. He plead “Not Guilty.” Edward Coke, in a damning speech, said Garnet had “his finger” in every Catholic intrigue against the government since 1586, including an earlier plot to assassinate Queen Elizabeth. Despite a total lack of supporting evidence, Coke called Garnet “the author” of the gunpowder plot. He accused Garnet of sending an envoy to the Pope to gain his blessing for the treason. A jury of London citizens took only fifteen minutes to convict Garnet of treason. He was hanged in St. Paul’s Churchyard on May 3. Speaking to the crowd before he climbed the ladder on a day Catholics celebrated as the day of the finding of the cross for the crucifixion of Jesus, Garnet said, “Upon this day I thank God I have found my cross.”

Father Henry Garnet

Father Oldcorne was also tried and hanged. Father Tesimond and Father Gerard were luckier. Tesimond smuggled himself aboard a cargo ship full of dead pigs and made it to France, then to Rome. Father Gerard also managed to slip out of England and to safety, dying in Rome in his seventies. He wrote a Narrative of the events surrounding the Gunpowder Plot.

In the aftermath of the plot, Parliament passed new laws punishing Catholics. Catholics were forbidden from practicing law or serving as officers in the Army or Navy. They were prohibited from possessing weapons, except in some cases of self-defense. They were prohibited from obtaining university degrees, denied the right to vote in local elections, and required to marry in the Anglican Church. A bill to require all Catholics to wear red hats was introduced in Parliament, but ultimately defeated.

King James died in 1623 and was succeeded by his son, Charles. King Charles I married a Catholic, Henrietta Maria, in the first year of his reign, offending many English Protestants. Charles had a contentious and troubled relationship with Parliament, which he dissolved three times, once for eleven years. He reassembled Parliament only when necessary to raise funds. Civil wars broke out in England, with the side supporting Charles defeated. Charles I was imprisoned, tried for treason at Westminster Hall, and executed.

In memory of the failed gunpowder Plot, ten men of the King’s bodyguard search the vaults underneath the House of Lords each year before the opening session of Parliament.