MARCUS TULLIUS CICERO

From Marcus Tullius Cicero: Seven Orations, edited by Walter B. Gunnison and Walter S. Harley

(Silver, Burdett and Company)(1912)

1. Early Life. - Marcus Tullius Cicero, the foremost Roman orator and writer, was born Jan. 3, 106 B.C. His birthplace was Arpinum, a small country town about seventy miles southeast of Rome, famous also as the birthplace of Marius. His father, a member of the equestrian order, was descended from a family of old standing. Quintus, a younger brother of Marcus, became a praetor at Rome, and afterwards won distinction as one of Caesar's lieutenants in Gaul. The two brothers were early taken to Rome and placed under the care of the best instructors. One of these was Archias, the Greek poet, whose citizenship the orator defended in later years before Quintus, when the latter was presiding judge.

After a general training in grammar, rhetoric, and the Greek language, Marcus began the study of law under Mucius Scaevola, the greatest lawyer of his time. This study he supplemented by attending the courts and the Forum, listening to such advocates as Crassus and Antonius. Then at the age of eighteen a short military campaign under Pompeius Strabo, uncle of Pompey the Great, gave Cicero all the experience he desired as a soldier. Gladly he resumed his studies, - rhetoric, logic, philosophy, and oratory, - pursuing them for two years, at Athens, in Asia Minor, and at Rhodes. At Athens he met Pomponius Atticus, who became his intimate friend and correspondent. At Rhodes, he was instructed by the celebrated rhetorician, Apollonius Molo, who also taught Caesar. It was this instructor who said, after listening to the young orator, "You have my praise and admiration, Cicero, and' Greece my pity and commiseration, since those arts and that eloquence, which are the only glories that remain to her, will now be transferred to Rome."

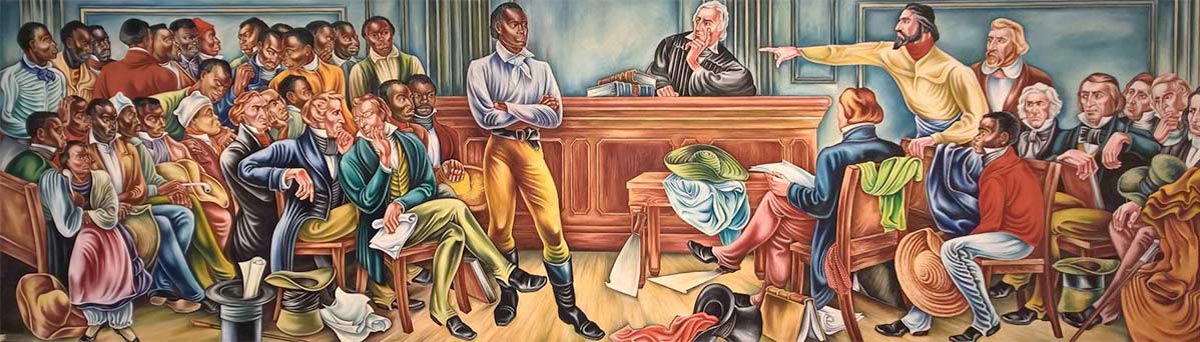

2. Cicero as an Advocate. - Cicero's first appearance as an advocate was in 81 B.C., in a civil suit in defense of Publius Quinctius, with the brilliant Hortensius as the opposing counsel. The following year he appeared in a criminal suit defending Sextus Roscius against a plaintiff who was a favorite of Sulla. His success in winning the case was therefore a· special triumph. In 77, after his return from foreign study, he resumed the practice of law, in which he was destined soon to take the leadership.

3. Cicero's Early Political Career. -It is significant of Cicero's qualifications that being a novus homo, i.e., one whose ancestors had never held office, he himself was elected to the four offices of the cursus honorum at the earliest legal age: quaestor at thirty, curule aedile at thirty-six, praetor at thirty-nine, and consul at forty-two. The quaestorship in 75 B.C. was spent in the province of Sicily, where his justice and impartiality endeared him to the people, while he greatly increased his popularity at home by sending grain from the province at a time of great scarcity. The holding of this office entitled Cicero to a seat in the Senate for life. Five years later the Sicilians appealed to Cicero to prosecute their Roman governor Verres, for tyranny and extortion. He conducted the impeachment with such skill that Hortensius, the defendant's counsel, gave up the case and Verres voluntarily went into exile.

In 69, as curule aedile, Cicero pleased the people by the public games which he furnished in good taste, though not with the lavish expenditure of his wealthier predecessors. His praetorship in 66 was made memorable by the passing of the Manilian Law, conferring upon Pompey supreme command in the war with Mithridates. Cicero's speech in behalf of the bill was the first he delivered to the people from the Rostra, an oration noted for its perfect form (see p. 243). By means of it he won the favor of Pompey, who was soon to become an important political factor, and, while incurring the opposition of the senatorial party, he secured the support of the populace. It paved the way to the consulship.

4. Cicero's Consulship. - Declining the governorship of a province at the close of his term as praetor, Cicero devoted his attention to securing the highest prize, the consulship. His name was presented in 64 B.C., with five other candidates, including Antonius and Catiline. Cicero owed his election to his clean record, which secured for him the solid support of the equites, his own order, and of many patricians of the better sort. He was the first novus homo to be elected since Marius, his fellow Arpinate. Antonius, second in the contest, became his colleague.

During his term he opposed the agrarian law of Servilius Rullus, defended Rabirius, an aged senator falsely accused of murder, and also the consul-elect, Murena, charged with bribery. But the main event of his consulship, and indeed of his life, was the suppression of the conspiracy of Catiline (see p. 181). This task was the more difficult because his colleague was in sympathy with the conspirators, and Caesar and Crassus had supported Catiline in his candidacy. Furthermore, there was no strong garrison in Rome at the time, for the legions were with Pompey in the East, and the nearest troops were in Cisalpine Gaul. It was the consul's prompt action that made him pater patriae, and honored him with a 8upplicatio, the first given to a civilian.

5. Cicero in Exile. - Having passed the goal of his political ambition, Cicero spent the next four years as an active member of the Senate. In 62 B.C. he delivered his oration for the poet Archias, his former teacher (see p. 269). He also defended P. Cornelius Sulla, who was charged with complicity in the conspiracy of Catiline. In private life there was much that added to the enjoyment of the honors he had earned. His house was on the Palatine Hill, the best residential section of Rome. He had villas or country seats at Antium, Cumae, Formiae, Pompeii, and Tusculum, with their libraries and works of art.

But a cloud hung over his pleasures. On the last day of his consulship, as he ascended the Rostra to give an account of his administration, Metellus, the tribune, had tried to prevent him by declaring that a magistrate, who had put Roman citizens to death without trial, should not himself speak. The gathering storm of opposition burst in the tribuneship of Clodius, 58 B.C. This profligate patrician had become the personal enemy of the orator because the latter had testified against his character. As the agent of the triumvirs whom Cicero had offended, he proposed a bill that whoever had put to death a Roman citizen without trial should be outlawed. It was evident against whom it was aimed. Failing to receive assistance from Pompey and the consuls, Cicero went into voluntary exile. Immediately another bill of Clodius was passed, declaring Cicero a public enemy, confiscating his property, and prohibiting him from fire and water within four hundred miles of the city. Cicero fled to Southern Italy, thence to Greece and Thessalonica. This was about the time of Caesar's battle with the Helvetians. The rest of the year he remained crushed in spirit and hopeless, notwithstanding the consolation and kindness extended to him by the provincials.

But in Rome opposition was turning to favor. Clodius had lost his hold. Pompey and the new consuls and tribunes of 57 urged the return of the exile. A month after the bill recalling him was passed in the assembly of the people, he reached Rome. His homeward journey was marked with demonstrations of affection. His entry into the city was like a triumphal procession. Later his house on the Palatine and his villas were rebuilt at the public expense.

6. Cicero as Ex-consul. - Cicero resumed his place in the Senate and in the courts, but his life was one of weakened influence. His friendship was sought by Caesar, and finally won, so that he wrote to Atticus, "The delightful friendship with Caesar is the one plank saved from my shipwreck which gives me real pleasure." It was after his return from exile that Cicero began to write upon rhetorical and philosophical subjects (see sec. 10). In 53 B.C., he was honored with an appointment to the college of augurs. In 52, while attempting to speak in behalf of Milo, who was clearly guilty of the murder of Clodius, he was humiliated by failure, breaking down "in the presence of the drawn swords of the soldiers, and of the intense excitement of the bystanders." The oration, which was delivered only in part, was afterwards written out, and is one of his best. The following year Cicero was made governor of Cilicia, a province that had been grossly misruled by his predecessor. The new governor won the hearty gratitude of his subjects by his reforms in many ways, and by subduing their enemies with his legions. He was proclaimed imperator, and on his return to Rome would probably have been awarded a triumph, had the citizens not been distracted by Caesar's crossing of the Rubicon.

7. Cicero and the Civil War. - Cicero's position between Caesar and Pompey was indeed difficult. Both leaders had claims upon his friendship. Failing as a peacemaker, he finally took the side of Pompey, following him to Greece. After Caesar's victory at Pharsalus, he returned to Brundisium, awaiting for months the will of the conqueror, until the message came with a generous offer of pardon. This was in 47 B.C. With but little interest in politics, Cicero sought comfort in writing. Three busy years followed, in which he produced four works on rhetoric and oratory, three on ethics, two on philosophy, besides essays on other subjects. Domestic sorrows came. His wife Terentia was estranged, and finally divorced. This was followed by the death of his only daughter Tullia, to whom he was devotedly attached.

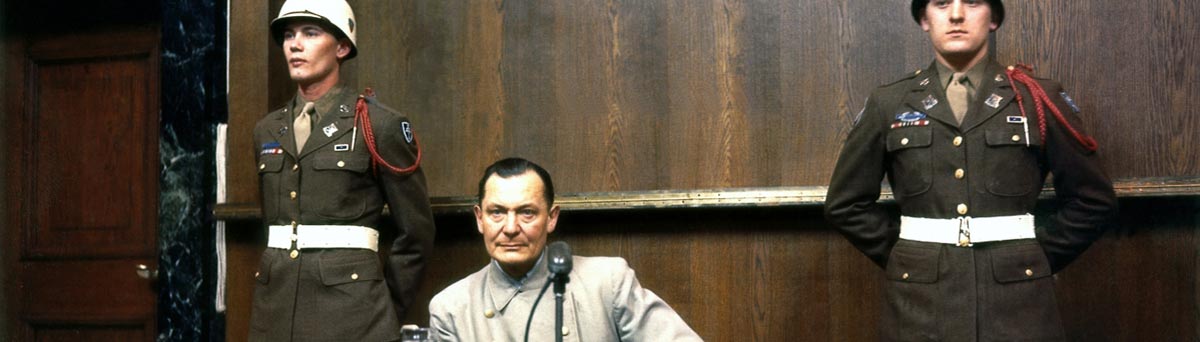

Then came the assassination of Caesar in 44 B.C., which in the course of events, Cicero was more than ready to approve. Once again, at the age of 63, he threw his energy into the struggle for the freedom of the republic. He became the life and soul of the senatorial party, aiding the young Octavianus in his claims against Antony. His last oratorical efforts were called forth in the fourteen" Philippics," hurled against Antony, in which he declared the tyrant to be a public enemy, and called upon the Romans to maintain their liberty. But the voice of her greatest orator could not save the state.

8. Cicero's Assassination. - The formation of the second triumvirate blasted all hopes of the patriots. Once more the proscription lists were made, and to satisfy Antony, the young Octavianus consented to sacrifice Cicero. His brother Quintus was also proscribed. Marcus might have made his escape, but was overtaken by the assassins near his villa at Formiae, December 7, 43 B.C. His faithful slaves would have fought to the end, but he permitted no resistance. It is recorded that his head and hands were taken to Rome and in mockery nailed to the Rostra by order of Antony.

9. Cicero as an Orator. - " It happened many years after," writes Plutarch,” that Augustus once found one of his grandsons with a work of Cicero’s in his hands. The boy was frightened and hid the book under his gown; but the emperor took it from him, and standing there motionless, read through a great part of the book; then he gave it back to the boy and said: 'This was a great orator, my child; a great orator, and a man who loved his country well."

Rome was a nation of orators. Not only did Cicero hold the first place among them, but his influence has been recognized by all men of eloquence since his day. To natural ability, a commanding voice and a pleasing personality were added long and careful discipline and experience. It is true that he argued chiefly as an advocate, often exaggerating or evading facts in order to emphasize. He was criticized for being verbose, but this defect he partly corrected. With his incisive wit, his keen sense of humor, his wonderful mastery of words, he swayed the people and the Senate at his will. Of one hundred and seven orations attributed to Cicero, over fifty have been preserved entire, with fragments of twenty others. Most of these were revised for publication after being delivered.

10. Cicero as a Writer. - The name of Cicero is the greatest in Roman literature. Mackail says, "Cicero's imperishable glory is that he created a language which remained for sixteen centuries that of the civilized world, and used that language to create a style which nineteen centuries have not replaced, and in some respects have scarcely altered. He stands in prose, like Virgil in poetry, as the bridge between the ancient and the modem world." One can hardly understand how a. busy man could find time to write so much upon so many subjects. His writings, as they have come down to us, fill ten volumes, about five thousand pages. Besides his orations and letters we have his works on rhetoric and philosophy. With his broad experience no one could write with more authority than he upon rhetoric and oratory. In his De Oratore, Brutus, and Orator, he treats of the ideal orator, his education and training, and the history of oratory down to his own time.

The treatises in philosophy were written in the last years of his life. In 46-44 B.C. he produced fifteen works, including De Republica, De Legibus, De Officiis, De Amicitia, De Senectute, De Finibus, De Natura Deorum, and the Tusculan Disputations. He had studied Greek philosophy from his youth. But very little had been written in Latin on this subject. To reproduce the thoughts of the Greeks without aiming to be original, to teach the lessons of philosophy to his countrymen in their own tongue, this was his task. Of the Tusculan Disputations it was Erasmus who said: "I cannot doubt that the mind from which such teachings flowed was in some sense inspired by divinity. I always feel a better man for reading Cicero."

11. Cicero's Letters. - To the modern world most interesting are the letters of Cicero. Of these we have over eight hundred, written to his family and friends (Ad Familiares), to his intimate friend and publisher, 'T. Pomponius Atticus (Ad Atticum), to his brother Quintus (Ad Q. Fratrem), and to Marcus Brutus (Ad M. Brutum). They cover a period of twenty-five years, 68 to 43 B.C., and are a priceless source of information of the times of Cicero, the last days of the republic. And yet as we read these charming and natural expressions of the great Roman, we are impressed with their modem tone and our common civilization.

12. The Character of Cicero. - Historians vary greatly in their estimate of Cicero. Perhaps it is nearest the truth to say that he had many weaknesses but much strength. He was emotional, vain, sensitive. As a statesman he made many mistakes. He failed to grasp the supreme problems of his time. He lacked force, will, and aim. He was vacillating in the civil war, but his choice of affiliation had to be made between two evils. That he was a patriot there can be no doubt. His greatest desire was to save and free the republic. That he was honest and incorruptible is shown in his provincial administration. He was a man of peace and honor, pure in life and purpose, and sympathetic with the oppressed. A biographer well says: "His fidelity to his prudent friend Atticus, his affection to his loyal freedman Tiro, his unfailing courtesy toward his wife Terentia, the love he lavished upon his daughter Tullia, his unworthy son Marcus, and his sturdy brother Quintus, stand forth in striking contrast to the coldness of the typical Roman of his day!'