The Security Hearing of J. Robert Oppenheimer (1954): An Account

by Douglas O. Linder (2020)

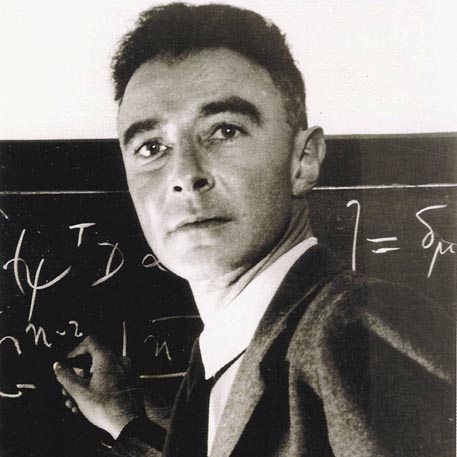

J. Robert Oppenheimer, testifying

Robert Oppenheimer, “the father of the atomic bomb,” never faced an actual criminal trial, it just seemed and felt like one. Convicted of no crime, Oppenheimer lost neither his life nor his liberty, merely his security clearance. Nonetheless, for the director of the Manhattan Project to lose his access to sensitive documents and other materials relating to the nation’s nuclear program is a testament to the powerful grip communist witch-hunting had on the United States in the early 1950s. It is fair to say that Oppenheimer was the most prominent victim of the McCarthy era. Moreover, the 993-page hearing transcript prepared by the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC), In the Matter of Robert Oppenheimer, was as Oppenheimer’s Pulitzer-Prize winning biographers called in their book American Prometheus, “a seminal document of the early Cold War.” Oppenheimer, the philosopher-scientist, is a compelling figure, and the story of his defeat, which was also a defeat for American liberalism, is a compelling story.

Background

Robert Oppenheimer was born in New York City in 1904, the son of wealthy, non-observant Jewish parents. The Oppenheimer family had an impressive art collection, including works by Picasso, Vuillard, and three Van Gogh originals. Robert has a younger brother named Frank, who would also become a nationally prominent physicist.

Robert was a superb student, with interests as varied as French literature and mineralogy and chemistry. After entering Harvard College, Robert suffered a colitis attack which led to the family’s decision to hire an English teacher to work with him during his recovery. The teacher, Herbert Smith, took Robert to New Mexico, beginning Oppenheimer’s long-term love affair with horseback riding and the American Southwest. Returning to Harvard, Oppenheimer developed a strong interest in experimental physics. He graduated summa cum laude in just three years.

After graduation, Robert studied physics in Europe, working with some of the giants in the field, including Max Born at the University of Gottingen. During this period, Oppenheimer became a chain smoker. Often he was so focused on his work that he neglected to eat for long periods of time. But his reputation as a brilliant theoretical physicist quickly developed, and Robert became friends with such scientists as Werner Heisenberg, Enrico Fermi, and Edward Teller. Some fellow students, however, resented his enthusiasm and intensity, accusing him of essentially taking over seminars with his constant parade of observations and questions.

When Robert returned to the United States in 1927 after receiving his doctorate, he was awarded a fellowship at Caltech, where he worked closely with Linus Pauling (until, that is, Pauling decided Robert had taken too much of an interest in his wife) in attacking the nature of the chemical bond. The next year, Oppenheimer returned to Europe, giving lectures on quantum physics and other subjects, in Dutch, at the University of Leiden. The following year, Oppenheimer accepted a faculty appointment at Berkeley, where he would continue teaching and researching for fourteen years. His students found him mesmerizing. They called him “Oppie.”

Oppenheimer’s academic interests were broad and his contributions to the field of physics great. He worked with Ernest Lawrence on the development of the cyclotron. He produced major advances in quantum field theory, nuclear physics, spectroscopy, and general relativity studies. In 1930, he published a paper that predicted the existence of the positron, and in 1938 a paper that predicted the existence of black holes. Oppenheimer’s work is credited with leading to a resurgence of scientific work in the field of astrophysics. Among other top scientists, Oppenheimer was known for his elegant solutions, his ability to inspire others to great work, and for his impatience—he never wrote long papers and sometimes his mathematics was a bit sloppy. He was also considered somewhat eccentric, and had a passion for subjects ranging from poetry to Hinduism that many other scientists could not relate to.

Beginning in the mid-1930s, Robert became increasingly interested in civil liberties and liberal causes. In 1934, he gave 3% of his annual salary to support physicists fleeing Nazi Germany. He attended rallies in support of union causes and donated to a variety of progressive causes that would become suspect in the McCarthy era. He was especially active in support of the Republican (anti-fascist) cause in the Spanish civil war. He also, during the period of 1937 to 1942, was a member of a “discussion group” that included Communist Party members. As a result of contacts such as these, the FBI opened a file on Oppenheimer in March 1941.

While Oppenheimer never became a member of the Communist Party, he had many friends who were. One of his lovers in the late 1930s was Jean Tatlock, a student at the Stanford School of Medicine and a writer for the Western Worker, a Communist Party newspaper. The couple broke up in 1939. Later that year, he began dating Kitty Puening, a Cal campus radical and a former member of the Communist Party. (It should be noted that in the late 1930s, membership in the Communist Party in the United States was reaching its peak. Little was known at the time about the purges, brutality, and extreme deprivation of basic liberties that would later be understood to be the characteristics of Stalinist Russia.) Robert and Kitty married in 1940. They had two children. A son, Peter, was born in 1941. Three years later, Kitty gave birth to a daughter, Toni. Robert was not a faithful husband. Just a few years into his marriage, he was seeing his old lover, Jean Tatlock, again.

Director of the Manhattan Project at Los Alamos

President Franklin Roosevelt approved a crash program to develop an atomic bomb in October, 1941, shortly before the United States entered World War II. FDR’s decision came two years after he had met with Alexander Sachs, a longtime advisor and friend to discuss a letter written by Albert Einstein to Roosevelt that suggested that fission chain reactions using uranium could likely produce a chain reaction which, if properly harnessed, could lead to the development of “extremely powerful bombs.” Einstein worried that the German government was working to develop such bombs and urged that the U.S. do likewise or face potentially devastating consequences.

In spring of 1942, National Defense Research Committee Chairman James Conant invited Oppenheimer to lead research on fast neutron calculations, a necessary step in understanding the process which could create the chain reaction for atomic bombs. Oppenheimer’s title was “Coordinator of Rapid Rupture.” By September, Oppenheimer’s name was being mentioned as a leading candidate to direct a secret weapons lab with the mission of producing atomic bombs for possible use in the war. The main strike against Oppenheimer was his known association with communists. In answering a security questionnaire, Oppenheimer candidly admitted his friendships with communists and his past donations to “communist front” groups.

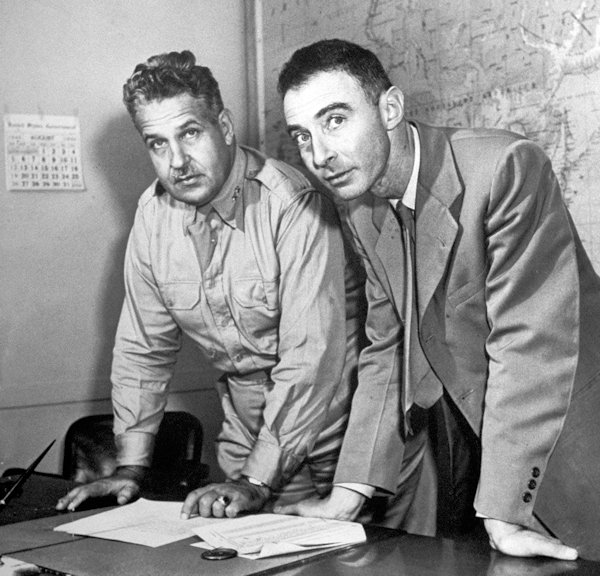

Despite his left-wing beliefs, Conant and other influential figures in the War Department considered Oppenheimer the best man for the job. In September 1942, a career Army officer, Colonel Leslie Groves, politically conservative and authoritarian by nature, took charge of what was designated the Manhattan Engineer District, the project to build an atomic bomb. Oppenheimer and Groves met in October, and despite their stark political differences, hit it off. Oppenheimer later said, “Groves is a bastard, but he’s a straightforward one!” Groves called Oppenheimer “a real genius” and was taken by his idea of locating the lab in an isolated rural site. Groves offered Oppenheimer the job.

Col. Leslie Groves and Oppenheimer

By the fall of 1942, Oppenheimer and his students had begun work exploring the feasibility of an atomic bomb. Oppenheimer also had contacted several key scientists to explain his mission. While the precise parameters of the project Oppenheimer was leading were known to relatively few, it was a “more or less an open secret” that he was up to something big relating to the war effort. By late fall, the Soviet Union had decided it would like to know more about what Professor Oppenheimer was up to.

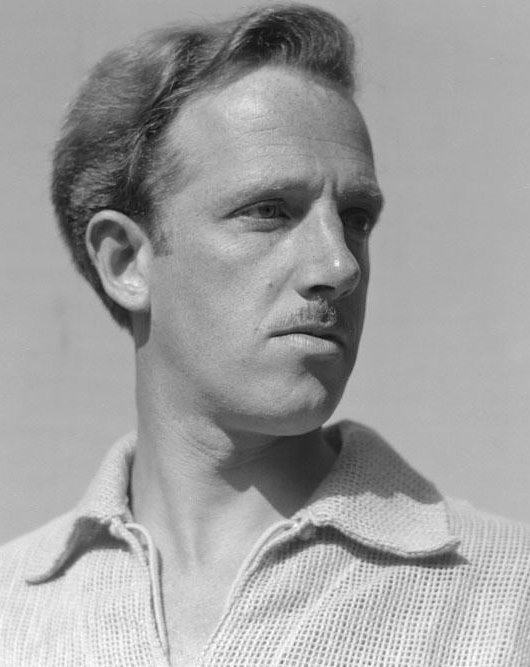

In the winter of 1942-43, when Oppenheimer and his wife were preparing to leave Berkeley to begin work in an undisclosed location, they invited over to dinner their good friends, Hakon and Barbara Chevalier. It turned out to be a fateful occasion that would shape much of the rest of Oppenheimer’s life.

Hakon Chevalier was not a scientist. He was a professor of French literature at Berkeley. He was also naïve, idealistic, and believed that the Soviet Union should know what we know about the feasibility of atomic weapons. Sometime before his dinner invitation to the Oppenheimers, Chevalier had been approached by George Eltenton, a British physicist friend, working for Shell Oil, who had been in recent contact with a Soviet Agent based in San Francisco named Peter Ivanov. Ivanov had asked Eltenton, a man highly sympathetic to the Soviet Union and who some—but certainly not all—historians believe to have actually been a Soviet Agent himself, if he knew anyone who could approach Oppenheimer in the hope that he might agree to provide information about the atomic bomb project to the Soviets. Eltenton thought of Chevalier.

Haakon Chevalier, a friend of Oppenheimer's

Oppenheimer went into the kitchen to mix martinis for his guest. Chevalier followed him into the kitchen. Chevalier told Robert that Eltenton had asked him to see if Oppenheimer would be willing to pass along news of his work to a Soviet diplomat Eltenton knew at the San Francisco consulate. Oppenheimer was deeply disturbed by the request and, by his own account, called the proposal “treasonous.” (Chevalier said later he was merely reporting the request, rather than asking Oppenheimer to serve as a conduit, but his own wife, years later, would claim he was completely in favor of getting as much information about the project as possible to the Soviet Union.) After dismissing the suggestion and finishing mixing the martinis, Robert and Hakon rejoined their wives. If Oppenheimer had promptly reported the solicitation to security officials, the final two decades of his life would have been far less stressful. But he didn’t.

In November 1942, shortly before his fateful kitchen conversation, Oppenheimer showed a mesa in New Mexico, a place with a grand view of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains, to Colonel Groves. There was a boy’s school on the mesa that Oppenheimer suggested might be a suitable site for a lab that would do the secret work necessary to construct an atomic bomb. When Groves saw Los Alamos, he announced, “This is the place.”

Despite his eccentricities and lack of administrative experience, Oppenheimer, according to his biographers Kai Bird and Martin Sherwin, “metamorphosed into a charismatic and efficient administrator” of the Manhattan Project. One young Harvard scientist, Robert Wilson, who worked under him at Los Alamos, said of Oppenheimer, “When I was with him, I was a larger person. . . . I just idolized him.” Los Alamos opened in March 1943. A year later, 3,500 people were at work there. At its height, in the summer of 1945, the outpost had grown to 4,000 civilians and 2,000 military.

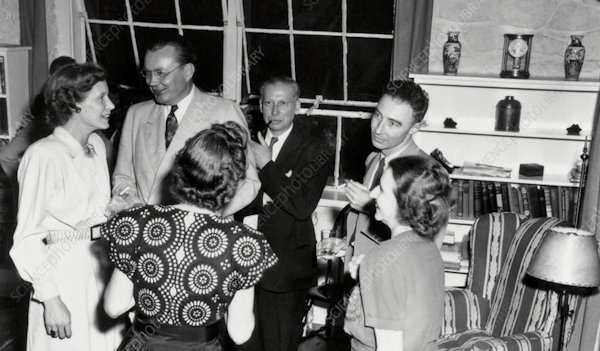

Oppenheimer (upper right) at a party in Los Alamos

On July 20, 1943, Oppenheimer was issued his security clearance. But security-minded people like FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover continued to worry that Robert might be a risk. In September 1943, Hoover wrote a memo to the Attorney General indicating that the Bureau had determined from a wiretap that Jean Tatlock, a known Communist Party member, “has become a paramour” of Oppenheimer. Counter Intelligence Corps assigned a “bodyguard” to Oppenheimer who was in reality a CIC agent. His phone was tapped, his office wired, his mail monitored.

In August 1943, Oppenheimer mentioned to Colonel Groves the kitchen conversation he had months before in Berkeley. He gave Groves the name of George Eltenton, information that Groves passed on to military security officials. Some days later, Army intelligence officer Colonel Boris Pash interviewed Oppenheimer about how he had learned of Eltenton’s interest in acquiring secret information about the bomb project. Not wanting to reveal the name of his close friend Chevalier, Oppenheimer concocted a story about Eltenton making a series of approaches to other people, “who were troubled by them and sometimes discussed them with me.” He suggested that the people who came to him were bewildered by Eltenton’s requests, not seeking his cooperation. Asked specifically the names of people who approached him, Oppenheimer refused to answer—only piquing, of course, Pash’s interest. In his answers to Pash’s questions, as Bird and Sherwin note in American Prometheus, Oppenheimer “unknowingly had swallowed a time bomb” that would explode in another decade. While Pash thought Oppenheimer’s refusal to provide names outrageous, Colonel Groves suggested it showed “his typical American schoolboy attitude that there is something wicked about telling on a friend.”

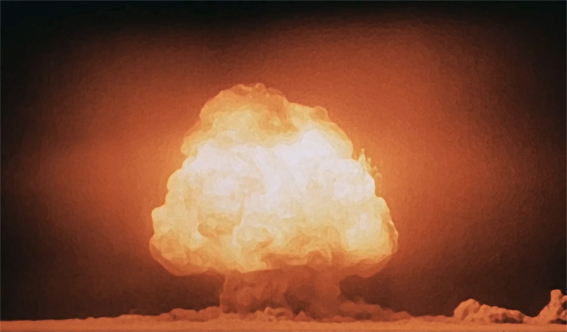

The Trinity explosion

On July 12, 1945, in the desert sixty miles northwest of Alamogordo, New Mexico, the atomic bomb created by Los Alamos scientists had its first test. Oppenheimer, who spent the night before chain smoking, reading poetry, and pacing, was 10,000 yards from ground zero, lying facedown, when the fireball erupted. The night turned to day, the fireball changed in color from white to yellow to red as it rose in the sky, finally turning into a hovering purple cloud. An intense blast of heat, followed by a thunderous blast shot across the desert landscape. Oppenheimer said to his brother, lying next to him, “It worked.” Two decades later, in an interview on NBC, he would recall thinking at the time of a line from Hindu scripture: “Now I am become death, the destroyer of worlds.”

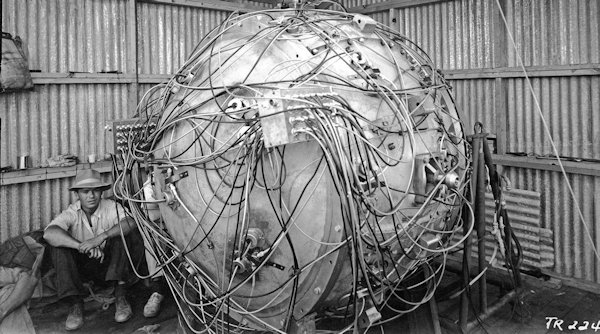

Oppenheimer's "Gadget", the world's first atomic bomb

On August 6, 1945, at 8:14 am local time, a B-29 aircraft named the Enola Gay dropped a uranium bomb over the city of Hiroshima, killing 225,000 people. Oppenheimer learned later that at the time an atomic bombs was dropped on Hiroshima, President Truman knew the Japanese were “looking for peace” and that a complete surrender likely could have been arranged without the destruction of major cities. Oppenheimer, who had supported the dropping of the bomb as means of saving U. S. lives that would be lost in a bloody assault on Japan, felt misled. Ever after, Oppenheimer viewed whatever government officials said with a heavy dose of skepticism.

Oppenheimer Pushes for Peace and Makes Enemies

Oppenheimer says farewell to Los Alamos (Oct. 16, 1945)

Oppenheimer resigned his directorship of Los Alamos in October 1945. After accepting a scrolled Certificate of Appreciation from Colonel Groves, he told a crowd of thousands gathered to bid him farewell, “If atomic weapons are added as new weapons of war to the arsenals of a warring world, the time will come when mankind will curse the names of Los Alamos and Hiroshima.” Just over a week later in Washington, Oppenheimer met with President Truman. He told the President, “I feel I have blood on my hands.” Truman replied the blood was on his hands: “Let me worry about that.” The incident bothered Truman, who later referred in a letter to Oppenheimer as “a cry-baby scientist.”

That fall, Oppenheimer and other leading scientists drafted a document warning against the dangers of an armed race and arguing for international control of nuclear weapons. At first, the Truman Administration expressed support for the message. Truman said, “The hope of civilization lies in international arrangements looking, if possible, to the renunciation of the use and the development of the atomic bomb.”

Oppenheimer’s outspokenness attracted the attention of J. Edgar Hoover, who sent a three-page summary of the FBI’s file on Oppenheimer to Truman in November 1945. A few months later, Hoover was suggesting to people that Oppenheimer might be preparing to defect to the Soviet Union. Hoover could hardly have been more wrong. In fact, Oppenheimer was growing thoroughly disillusioned with communism. Eight years later he summarized his feelings about communisms in a Reith Lecture delivered in London: “[O]nly a malignant end can follow the systematic belief that all communities are one community; that all truth is one truth; that all experience is compatible with all other; that total knowledge is possible; that all potential can exist as actual. This is not man’s fate; this is not his path; to…make him…the iron-bound prisoner of a dying world.”

Hoover approved a wiretap of Oppenheimer’s home in Berkeley. Over the next eight years, the FBI file on Oppenheimer would grow to include several thousand pages of wiretap transcripts, memos, and surveillance reports.

In June 1946, two FBI agents dropped by the house of Haakon Chevalier. They wanted to ask him questions about his conversation with Oppenheimer more than three years earlier. In September, they interviewed Oppenheimer about the same kitchen chat. Oppenheimer admitted lying. He told the agents he had concocted the story he told Pash earlier in order to protect his friend, Chevalier. So Oppenheimer was now on the record as having lied to military intelligence officials in 1943.

Meanwhile, Oppenheimer grew increasing concerned about the world’s future in a nuclear age. Asked what could be done if international controls on nuclear weapon development fails, Oppenheimer looked out a window and said, “Well, we can enjoy the view—as long as it lasts.” Oppenheimer, who had accepted a faculty position at Berkeley told friends that teaching now felt “irrelevant” and his major focus became saving the world from nuclear destruction.

The AEC Advisory Committee: Conant, Oppenheimer, McCormack, Howe, Manley, Rabi, amd Warner

Despite the security concerns of Hoover and his conservative political allies, Oppenheimer held a Q (atomic secrets) security clearance and was chairman of the AEC’s General Advisory Committee. In 1947, finding his teaching duties distracting, Oppenheimer took a new position as director of Princeton’s Institute for Advanced Studies, a think tank for prominent scholars whose numbers included, most notably, Albert Einstein. (Another scholar was Johnny von Neumann who, in 1952, unveiled the fastest computer in the world—the unpatented computer that would start the computer revolution.)

In October 29, 1949, a couple of months after the Soviet Union exploded its first atomic bomb, President Truman was made aware of the possibility of developing a thermonuclear bomb, called at the time by many “a Super.” The AEC, however, made a decision to oppose the development of a Super on both technical and moral grounds. They argued that the weapon was not necessary as a deterrent to protect American security. But Truman worried that if the U.S. didn’t develop an H-bomb, the Soviets would. He announced a program to study the feasibility of such a weapon.

The discovery that the Soviet Union had successfully stolen secrets from Los Alamos ratcheted up security concerns in the early 1950s. The most influential man in Washington anxious to put the security spotlight on Oppenheimer was Lewis Straus, one of the original commissioners of the AEC and, after his appointment by President Eisenhower in 1953, its chairman. Straus strongly favored development of an H-bomb and a massive build-up of America’s nuclear weapons, differing strongly with Oppenheimer on those points. Oppenheimer argued a nuclear war was unwinnable: “We may be likened to two scorpions in a bottle, each capable of killing the other, but only at the risk of his own life.”

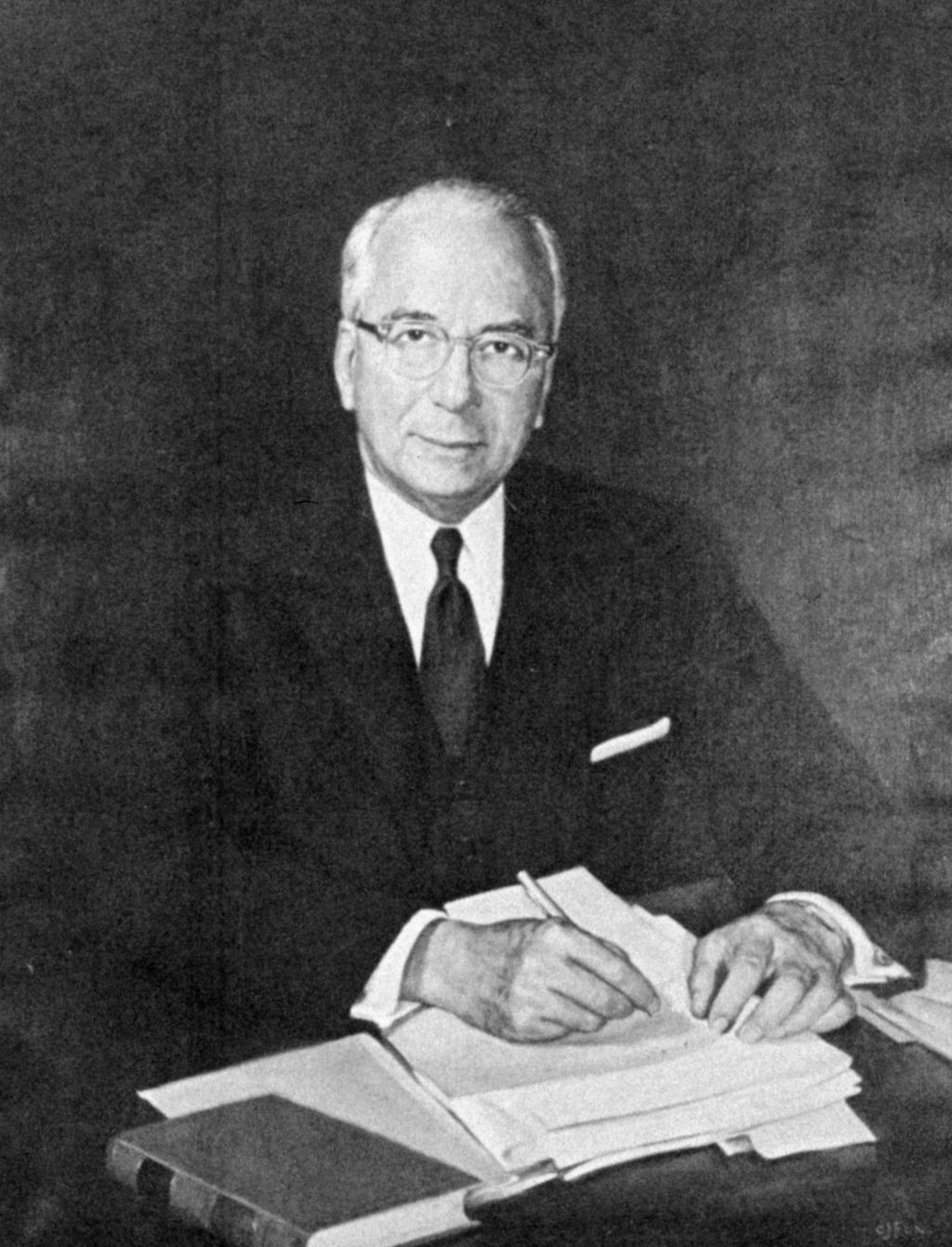

Lewis Straus, Oppenheimer's chief nemesis

In 1952, Oppenheimer announced he was “fed-up with Washington,” and announced his resignation from the AEC. He was persuaded, however, to remain available as a contract consultant and his security clearance was extended.

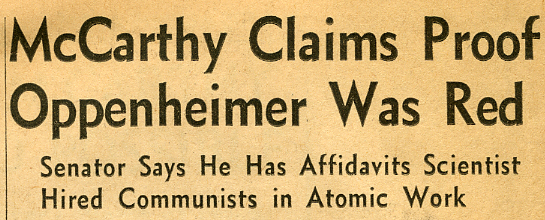

By 1953, with a Republican Administration in power, political forces began to move against Oppenheimer. Communist-hunting, with Senator Joseph McCarthy leading the hunt, was the talk of Washington. Oppenheimer stepped into an elevator on Capitol Hill one day and surprised to see McCarthy. “We looked at each other,” Oppenheimer said, “and I winked.” A few months later, McCarthy visited Hoover and proposed an investigation of Oppenheimer by his Senate committee, but Hoover discouraged the effort, arguing that more “spade work” had to be done. Oppenheimer, however, remained on McCarthy’s mind. In an April 1954 interview with Edward R. Murrow on CBS, McCarthy claimed that America’s efforts to build a hydrogen bomb had been deliberately sabotaged.

President Eisenhower and Lewis Straus

Straus did his best to sow suspicion of Oppenheimer with Eisenhower and others in his administration. In addition, he orchestrated a publicity campaign against Oppenheimer and encouraged his friend J. Edgar Hoover to aggressively investigate him. He also set a like-minded friend, William Borden, off on the task of preparing essentially a prosecution brief against Oppenheimer. Borden prepared a report on Oppenheimer which he delivered in November 1953. Borden’s conclusion: “more probably than not J. Robert Oppenheimer is an agent of the Soviet Union.” When Eisenhower read the report, he called the charges “very grave.” The president directed that a “complete bar” be immediately “erected between this individual and any information of a sensitive or classified character.”

Chairman Straus told Oppenheimer that the AEC had prepared a letter outlining charges against him. He asked Oppenheimer to agree to a termination of his contract as a consultant to the Commission and to his Q security clearance. Oppenheimer responded in a letter addressed “Dear Lewis.” He told Straus that if he were to agree, it would “mean that I accept and concur in the view that I am not fit to serve this government, now that I have now served for some twelve years. This I cannot do.” It was a day of high stress for Oppenheimer. It ended with him collapsing and falling unconscious on his bathroom floor.

Oppenheimer on Trial: The AEC’s Hearing to Remove His Security Clearance

Oppenheimer received a letter from the AEC outlining the formal charges against him on Christmas Eve of 1953. He was accused of working to convince “outstanding scientists not to work on the hydrogen bomb project,” of slowing down the development of the hydrogen bomb project by leading opposition to it, and with having known association with communists and lying to investigators about the Chevalier affair. The letter specifically mentioned his “intimate association” with admitted communist Jean Tatlock and employing several of his former students, known to be communists, in the atom bomb project. It was a political indictment, not a criminal indictment.

Oppenheimer hired an attorney and worked hard over the next few weeks to prepare his defense. His attorney, Lloyd Garrison, agreed that the charges looked “pretty bad.”

The process was stacked against Oppenheimer by Straus. Hoover had agents bug Garrison’s office, so whatever was said between the two men of consequence ended up in FBI summaries shared with Straus and the AEC’s “prosecuting attorney”, Roger Robb. Straus knew the wiretaps were illegal, but didn’t care. Straus also allowed FBI agents to guide AEC commissioners through the most negative information in Oppenheimer’s FBI file, while denying Garrison and Oppenheimer the opportunity to even examine the same file. Finally, Straus chose as the three members of the AEC security review board—the judges in the case—men who he believed would tend to be suspicious of Oppenheimer’s history. In Straus’s view, Oppenheimer represented a threat to the nation’s security and he was unwilling to let legal niceties get in the way of the right result.

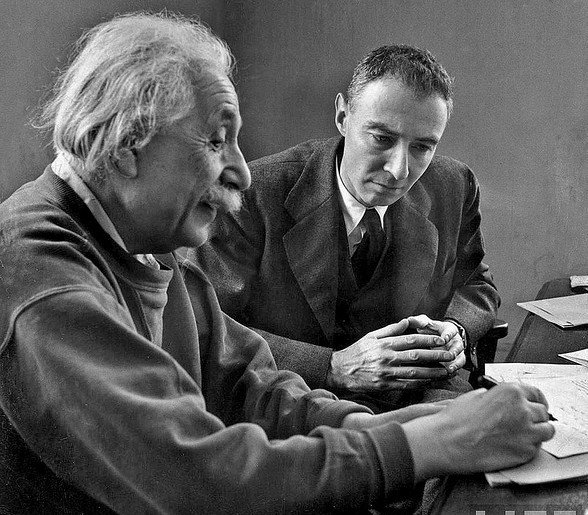

Albert Einstein and Robert Oppenheimer

Albert Einstein thought the charges against Oppenheimer were so “outrageous” that he should just resign rather than fight and lend legitimacy to the process. He knew, however, that Oppenheimer could never turn his back on America. “Oppenheimer’s not a gypsy like me,” he said. Einstein saw the security hearing as another depressing development in America’s drift toward militarism: “The German calamity of years ago repeats itself: People acquiesce without resistance and align themselves with the forces of evil.” Einstein issued a brief statement of support for Oppenheimer to the press: “I admire him not only as a scientist but also a great human being.”

On March 5, 1954, Oppenheimer submitted a 42-page response to the charges. It read like an autobiography. On the Chevalier incident, potentially the most damaging, Oppenheimer acknowledged that he should have immediately reported all the facts about the conversation to security officials. He pointed out, however, that without his providing information to security about the contact, Eltenton’s role as a Soviet agent might never have come to light.

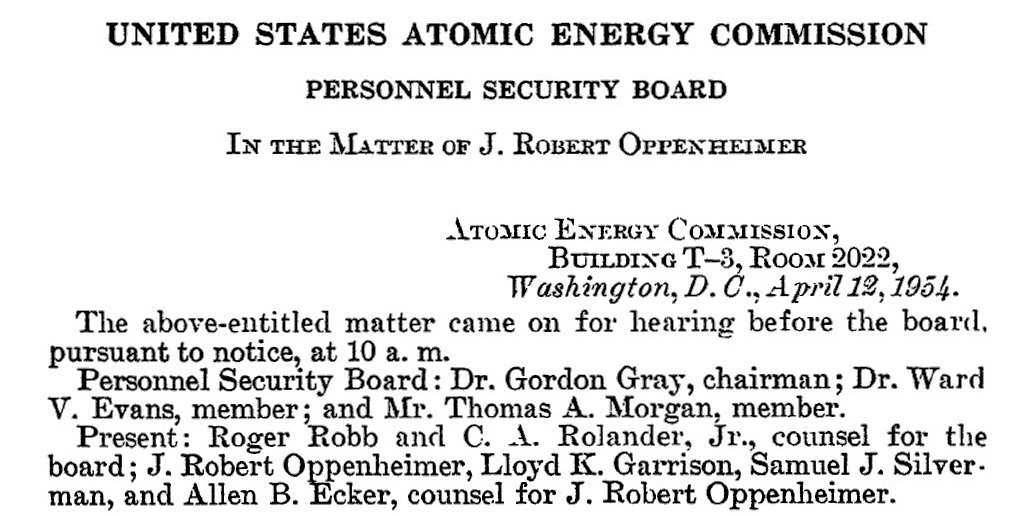

The hearing convened on April 12 in a temporary building on the Mall near the Washington Monument. Chairman Gordon Gray began the hearing with a reading of Oppenheimer’s “indictment,” followed by his letter in reply. Throughout the morning session, Oppenheimer appeared rather emotionless, seemingly resigned to his fate.

Gordon Gray, chairman of the security hearing

Following the long reading of the charging document and the reply, Gray asked Oppenheimer if he would like to testify under oath. He said he would. He took the witness chair and promised to tell the whole truth and nothing but the truth. Before the hearing was over, Oppenheimer would spend 27 hours on the stand.

Direct examination by his attorney, Lloyd Garrison, was the easy part. Things began to get very stressful on April 14, when Roger Robb began his cross-examination. Oppenheimer tried to make the point that being a member of the Communist Party, or being “a fellow traveler,” was a very different thing during the war, in the late 1930s and when the Soviets were our allies than it was during the Cold War Era of the hearing. Oppenheimer, under questioning, described himself as a “fellow traveler” from late 1936 to early 1937, then his interest began to taper off, “very much” so after 1942.

Asked why he told investigators that Chevalier had approached three persons on the project about Eltenton’s bid to acquire information about the project, when in fact to his knowledge Chevalier had approached only him, Oppenheimer replied, “Because I was an idiot.” Robb asked Oppenheimer, “And your testimony now is, that was a lie?” Oppenheimer replied, “Right.” Robb pushed the point asking whether it was “a fair statement” that he told not just one lie, “but a whole fabrication and tissue of lies.” Oppenheimer again replied, “Right.” Responding to a follow-up question from Chairman Gray, Oppenheimer explained his motive for lying: “So that when I made up this damaging story, it was clearly with the intention of not revealing who was the intermediary.” He tried to protect his friend, Chevalier.

Jean Tatlock

Robb also pressed Oppenheimer hard on his affair with Jean Tatlock, a member of the Communist Party. “You spent the night with her, didn’t you?” Robb asked. Oppenheimer answered “Yes.” Then Robb asked, given his directorship at Los Alamos in 1943, “Did you think that was consistent with good security?” Oppenheimer stumbled a reply, “It was, as a matter of fact. Not a word—it was not good practice.”

Robb also explored Oppenheimer’s opposition to the hydrogen bomb project: “Did you subsequent to the President’s decision in January 1950 [to proceed with development] ever express any opposition to the production of the hydrogen bomb on moral grounds?” Oppenheimer replied, “I would think that I could very well have said this is a dreadful weapon, or something like that.” Robb demanded to know whether Oppenheimer had “qualms” about the hydrogen bomb. Oppenheimer answered, “How could one not have qualms about it? I know no one who doesn’t have qualms about it.”

Oppenheimer and Groves in New Mexico

On April 15, General Groves testified. Asked by Garrison whether he could conceive of Oppenheimer committed a disloyal act, Groves replied, “I would be amazed if he did.” Groves said his interpretation of Oppenheimer’s lies relating to Chevalier were that they flowed from his “schoolboy attitude” that it was wrong to say “something wicked” about a friend. Groves said that if had thought for a minute that Oppenheimer was trying to protect a spy, he would have gone to the FBI.

Garrison called more than two dozen witnesses to vouch for the loyalty and integrity of his client. They included prominent scientists, diplomats, and politicians such as Hans Bethe, George Kennan, Gordon Dean, Johnny von Neumann, and James Conant. He also called John Lansdale, the former chief of security for the Manhattan Project. Lansdale said he “strongly believed” Oppenheimer was completely loyal to the United States. He attributed the fact that Oppenheimer was facing a hearing with the potential for loss of his security clearance as a “manifestation” of “the current hysteria of our times.” On cross-examination, Robb asked, “You think this inquiry is a manifestation of hysteria? Yes or no?” Lansdale answered, “I won’t answer that question ‘Yes” or ‘No.” I think the hysteria of the times over communism is extremely dangerous.”

George Kennan

George Kennan testified that he thought Oppenheimer “one of the great minds of this generation.” He considered him incapable of speaking dishonestly on any subject that had engaged the attention of his intellect: “I would suppose that you might just as well have asked Leonardo da Vinci to distort an anatomical drawing as that you should ask Robert Oppenheimer to speak dishonestly.” Dr. Vannevar Bush made the same point: Oppenheimer, he testified, was “now being pilloried and put through this ordeal for having the temerity to express his honest opinions.”

The most prominent scientist to testify against Oppeheimer was Edward Teller, a strong advocate for development of the hydrogen bomb. Teller made clear, however, that he didn’t appear as a witness to question Oppenheimer’s loyalty. He testified, “I have always assumed, and now assume, that he is loyal to the United States.” Nonetheless, Teller said he considered Oppeheimer a security risk, offering this conclusion: “I feel that I would like to see the vital interests of this country in hands which I understand better and therefore trust more.” Oppenheimer, Teller believed, lacked the “wisdom” and “judgment” to maintain his security clearance.

The hearing came to an end on May 5, 1954. The following day, Garrison delivered a three-hour summation. He called what Oppenheimer had been put through more of a “trial” than a “hearing.” He suggested Oppenheimer was a victim of the times: “There is more than Dr. Oppenheimer on trial in this room. . . The government of the United States is her on trial also.” He worried that America was “devouring her own children” and that the Board should judge not a few isolated incidents and statements, it should “judge the whole man.”

On May 23, the Board returned its verdict. By a two-to-one vote, the Board recommended that Oppenheimer’s security clearance not be restored. Although finding Oppenheimer to be a loyal citizen, it nonetheless deemed him a security risk. Gray and Thomas Morgan, for the majority, found that Oppenheimer’s conduct “reflected a serious disregard for the requirements of the security system.” They also found that his conduct in the hydrogen bomb program was “sufficiently disturbing” to suggest that his continuing participation in the program would not be “consistent with the best interests of security.” It is noteworthy that the Board did not find that Oppenheimer broke any laws or security regulations. It was, rather, in the Board’s view, a question of bad judgment.

Ward Evans wrote a dissent. He noted that Oppenheimer “did his job in a thorough and painstaking manner” and “hates Russia.” Evans said the hearing turned up nothing new. He concluded, “I personally think that our failure to clear Dr. Oppenheimer will be a black mark on the escutcheon of our country.”

Epilogue

The Board’s recommendation to not restore Oppenheimer’s security clearance was affirmed by the AEC on a four-to-one vote, with Commissioner Henry Smyth dissenting. Straus arranged for publication of a 993-page document, In the Matter of J. Robert Oppenheimer, as well as the 3,000 page transcript of the hearing. Straus and the AEC sent a message to scientists. If scientists worked for the government, they needed to think long and hard about dissenting on important government policy.

The stripping of Oppenheimer’s securing clearance made him into something of a martyred scientific figure, like Galileo. Los Alamos scientists, 282 strong, signed a letter protesting the AEC’s decision. CBS television commentator Eric Sevareid said of the decision, “He will no longer have access to the secrets in government files, and the government, presumably, will no longer have access to the secrets that may be borne in Oppenheimer’s brain.” Sevareid described Oppenheimer as “the scientist who writes like a poet and speaks like a prophet.”

Oppenheimer Beach on St. John

With the support of almost every member of the Institute’s faculty, Oppenheimer kept his position as director at Princeton. Disengaged from his duties in Washington, he found more time to travel. He purchased land and built a small beachside home on St. John, in the Virgin Islands. He made many friends on the island. One neighbor, John Green, called him “the gentlest, kindest man I have ever met.” In 1960, he visited Japan. He continued to speak out on political and scientific issues, publishing a collection of essays entitled, The Open Mind.

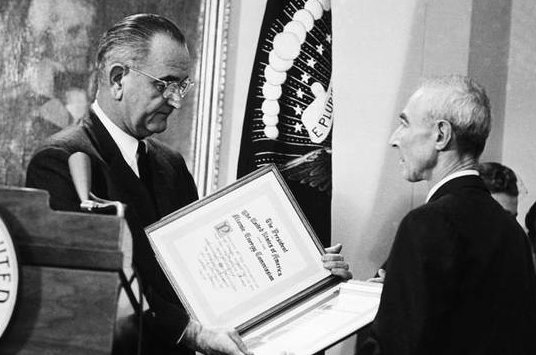

President Johnson presents the Fermi Award ti Oppenheimer in 1964

In 1964, President Lyndon Johnson awarded Oppenheimer the prestigious Enrico Fermi Prize in a White House ceremony. Accepting the award, Oppenheimer said: “I think it is just possible, Mr. President, that it has taken some charity and some courage for you to make this award today. That would seem to be a good augury for all our futures.”

In February 1966, Oppenheimer was diagnosed with throat cancer. He died one year later, on February 18, 1967, at the age of 62. His cremated remains were dropped into the waters of Hawksnest Bay off the island of St. John.

In December 2022, seventy years after Oppenheimer's security clearance was revoked, the decision was revoked by Secretary of Energy Jennifer Granholm. The Secretary described the 1954 revocation as the result of a "flawed process" that violated the Department's own regulations. Granholm said that evidence accumulated since 1954 has affirmed Dr. Oppenheimer's "loyalty" and "love of country."