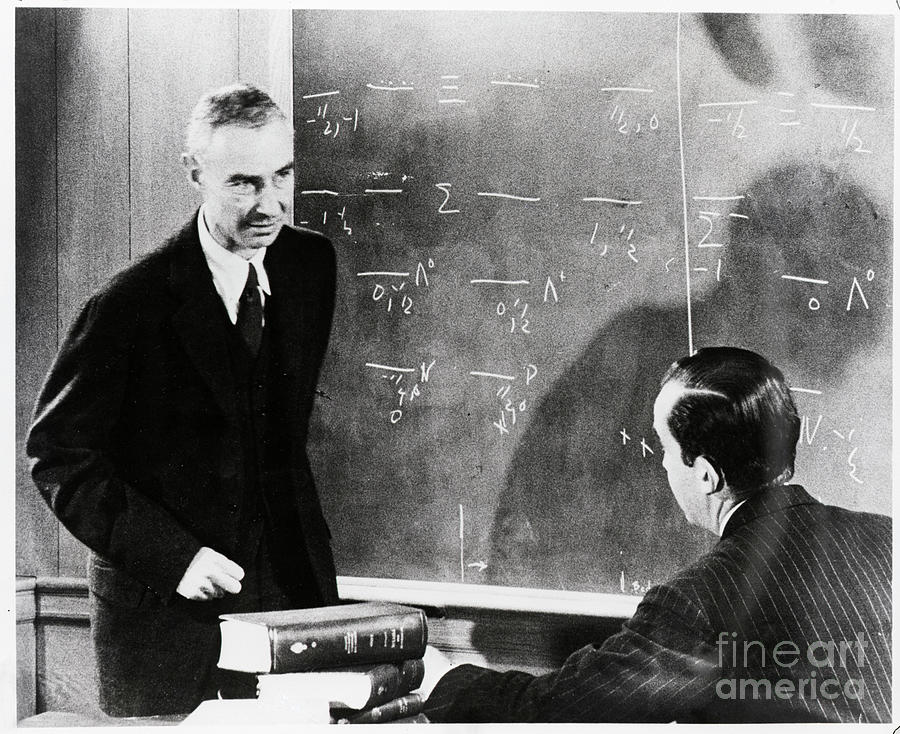

Edward R. Murrow Interviews Robert Oppenheimer on the CBS Show "See It Now" (Show #18)

Transcript of a Conversation with Dr. J. Robert Oppenheimer, January 4, 1955

Edward R. Murrow

MURROW: Dr. Oppenheimer, why don't we begin by your telling me a little about this Institute for Advanced Study — how it began?

OPPENHEIMER: Well, I—l will try. Of course, it began at the time when I wasn't anywhere near; and it's already a subject for historical research. I — I'm about to find someone to see if he can find out how it began.

MURROW: I have heard you describe it as a "decompression chamber."

OPPENHEIMER: Well, it is, for many people. There are no telephones ringing, and you don't have to go to committee meetings, and you don't have to meet classes, and the — it's especially for the few people who are here for life. The first years are quite — quite remarkable. Because most people depend on being interrupted in order to live. The work is so hard and failure is — is of course, I guess, an inevitable condition of success. So they're used to having — having to go — to attend to other people's business. When they get here, there is nothing of that, and they — they can't run away.

It's to help men who are creative and deep — and active and struggling scholars and scientists, to get the job done that it is their destiny to do. This is a big order, and we take a corner of it. We do the best we can. We — we suffer from limits of money, of wisdom, of space, and we know that if we get big, we — we will spoil everything. Because the kind of intimacy, the kind of understanding, the kind of comradeship that is possible in a place of this size is hard to maintain in a place tenJimes as big. But we are here as an institution —I don't mean in our individual capacities; but, as an institution, we are here to take away from men the cares, the pleasures, that are their normal excuse for not following the rugged road of their own — own life and need and destiny. . . .

MURROW: Well, what about the supply of scientists — the man-power pool — the training of the younger scientists?

OPPENHEIMER: I don't know. You see, that — that always is a very —I am very bad about it, because I work in my own life with rather few people as students. I always have. They wouldn't let me at undergraduates, because they are afraid I'd confuse them. I'd have a dozen or twenty men that I'd work with intimately. This Institute has a hundred people. I think in terms of the — of the rather good people rather than the number. But there's a lot of truth to that — a lot that's right about it, I mean. We — we are beginning to catch up on the mechanical side. We're just beginning to realize that if we want people to do very hard things, we've got — and want them to do it irrespective of whether they are rich or poor — we've got to provide money in some way, to see them through their training. If we want them to go into a profession which will never be very remunerative, we won't be successful unless we provide scholarships and that kind of thing. The training is "Operation Bootstrap." One great teacher, one great man of learning — changes a country. Denmark has one enormous figure in physics, and the whole country is altered by that. lapan has Yukawa, who was the first Japanese to come to the Institute after the war and who was sent here with Mac Arthur's blessings — a sign of the new relations between the countries. And now all the bright young Japanese want to learn theoretical physics — not all, but I mean — l exaggerate. So, I think that the statistics and the tables maybe don't tell the whole story.

MURROW: Tell me, is there a very widespread reluctance on the part of scientists in this country to work for the government?

OPPENHEIMER: No, I don't think so. This also gets very much distorted when it's — when it's talked about in sloganistic terms. You see, if you take a scientist who's excited by, and interested in a new discovery, he may have a problem as to whether he wants to do applied science — and for the government, that's what he would be doing. And that's a — that's a legitimate doubt; and if all the scientists in the country did applied science, it would be terrible for us. I think that scientists like to be called in and asked to advise on how to make the Voice of America a better thing. They like to be called in and asked for their counsel. Everybody likes to be treated as though he knew something. I suppose that — that when the government behaves badly in a field you are working close to, and when decisions that look cowardly or vindictive or shortsighted or mean are made, and that's very close to your area, then you get discouraged and you may — you may recite George Herbert's poem, "I Will Abroad." But I think that's human rather than scientific.

MURROW: Dr. Oppenheimer, are you worried about — the — all the impediments placed in the way of free intercourse, travel and exchange among scientists?

OPPENHEIMER: Very much.

Oppenheimer and Murrow

MURROW: I've been thinking, coming down here, and I think this is true — that had the McCarran Act been enforced, neither Fermi nor Szilard would ever have been permitted to enter the country, which would have been a rather expensive loss, I think.

OPPENHEIMER: Perhaps not even Einstein —I don't know. This is terrible. This is just terrible, and seems a wholly fantastic and grotesque way to — to meet the threat of espionage; just an enormous apparatus, surely not well designed for that, and terrible — for — for those of us who live with it. We are rightly shamed by the contempt that the Europeans have for us, and we are rightly embarrassed that we can't hold congresses in this country — that we can't — often don't let people go to congresses who are the most wanted. Year after year, we've met in Rochester to discuss the kind of basic physics that — There is one man who's the world's greatest in this, and very, very good. Ah, well, he sends his deputies and his representatives and so on, but he doesn't come. And that's not one situation — it's over and over again. This is a scandal. . . .

MURROW: Tell me, Dr. Oppenheimer, do you ever become frightened at what you are finding out here, in this area that can't be measured in either time or space?

OPPENHEIMER: I—you see, that's a real point. I only get frightened when — and it happens very rarely, I think —I have an idea. That is, what people find isn't frightening, but the understanding of it sometimes has this quality. I remember a man who was my teacher in Gottingen, who is in Chicago now. James Franck. He said, "The only way I can tell whether my thoughts are — really have some weight to them — is the sense of terror when I think of something new." Well, so, the kind of order that will come out of this — that is frightening; but the fact is that this, you see, is like walking through the woods and seeing that there are different kinds of flowers — and it's all very amusing. And so, it is when you try to see why there is necessity to it — why it is this way and no other way. Because all you can do here is guess in the night and correct in the daytime, and you have to try to find the mistakes.

MURROW: Is it true that humans have already discovered a method of destroying humanity?

OPPENHEIMER: Well, I suppose that really has always been true. You could always beat everybody to death. You mean to do it by inadvertence?

MURROW: Yes.

OPPENHEIMER: Not quite. Not quite. (Hesitatingly.) You can certainly destroy enough of humanity so that only the greatest act of faith can persuade you that what's left will be human. This is — this is a matter on which much, much, much, much more should be known. There's every reason for us to say what we — what we know, and above all, to say what we don't know. The genetic problems — the problems of what — what might happen in the future to the human species as a result of having radio-activity in the body or having radiation outside — the geneticists don't know enough to be sure of that. We do know what happens if you're near an explosion — a bomb explosion. We know it from experience and from common sense. The — the things we know ought to be in the public domain so people are fearful only in the measure in which fear is justified and — and rational. The things that aren't known should be talked about, because one of the ways to get things found out is — is to have it clear that we don't know the answers; and also one of the ways to — to give people the kind of responsibility and humanity which we would like, or think we have, is that they recognize when they don't know something, and take their very ignorance into account in their planning. This is too long an answer to your question, but I feel very. . .

MURROW: It certainly is not, and it brings me to another one that I wanted to ask very much, and that is: In this era that is more frightened and dominated than any previous one by scientists, their decisions, their discoveries — what about the poor uninformed civilian?

OPPENHEIMER: It isn't the layman that's ignorant. It's everybody that's ignorant. The scientist may know a little patch of something, and if he's a humane and intelligent and curious guy he'll know a few spots from other people's work. He may even be able to read a book. But — but his condition is a condition of everyone, which is, that almost everything that's known to man, he doesn't know anything about at all, or knows it only in a very sketchy way. And that's because it's — - it's gotten a bit complicated. The problem of — of a coherent civilization is the problem of—of living with ignorance and not — not being frustrated by it; so that you find occasionally a man who knows two things, and thaf intersection may be a great event in the history of ideas. Occasionally, a man may think that something is relevant or exciting which no one before thought concerned him professionally. That may change the history of the world. And these are the connections, these virtual connections, these casual and occasional connections, which make the only kind of coherence we have; that, and affection; that, and respect. That, and, I suppose, a kind of humanity. Now, if you look at the problem of science in government, then of course, it's possibly not really science. It's — it's pretty much practical application, because no one in the government of the United States needs to worry about whether the isotopic spin or the strangeness number are the real invariants of this subatomic work. They need to know, sometimes, things that are very hard to answer. Can a rocket enter the — the earth's atmosphere if it's gone a few thousand miles, and have a skin that isn't burned up? — and so on. They need to know: Is there any limit to the size of explosions you can make? They need to know all kinds of technical things. And these are not, in the narrow sense, the frontier of science, but they are technical and complicated. Some will understand one another in one area, some in another, and you get a kind of lacework of coherence. And that requires — l used the word "affection" before. For the government it might be better to say "trust." Though I think even for the government "affection" wouldn't be a hopeless word — take in the government itself, which consists of life. Take the President, or his Secretary of State, or his Secretary of Defense. All he can do is to be sure that in one way or another the advice he's being given is subject to criticism.

If he gets a statement of how it is — this will cost so many dollars and take so many years; this is impossible — that anyone who has a different view and the professional qualifications that make it interesting, can get to him. And I think that isn't too bad in the parts of the government I have been close to. That is, the atom, and military establishment, and the State Department. I think —/ think people have been able to — to tell their stories, and that — that the folly has been corrected. But if you mean the people outside the government. . . .

MURROW: Yes.

OPPENHEIMER: And I think that's more important. There — there is a — a really, a point that I feel most deeply, and I think I speak really now the voice of — of my profession: and that is the integrity of communication. The trouble with secrecy isn't that it inhibits science; it could, but in this country it's hardly been used that way. Technical things are — are really quite widely known, and those at the growing tip of—of any science are so far from practice that the — the people talk quite freely about them, and should. The trouble with secrecy isn't that it doesn 't give the public a sense of participation. The trouble with secrecy is that it denies to the government itself the wisdom and the resources of the whole community, of the whole country; and the only way you can do this is to let almost anyone say what he thinks — to try to give the best synopses, the best popularizations, the best mediations of technical things that you can, and to let men deny what they think is false, argue what they think is false. You have to have a free and uncorrupted communication. And this is — this is so the heart of living in a complicated technological world — it is so the heart of freedom, that that is why we are all the time saying, "Does this really have to be secret?" "Couldn't you say more about that?" "Are we really acting in a wise way?" Not because we enjoy chattering, not because we are not aware of the dangers of the world we live in, but because these dangers cannot be met in any other way.

MURROW: Well, if I may say so, I think you were speaking there, not only for your profession, but for mine — if it is a profession.

OPPENHEIMER: I—l'm sure of that.

MURROW: There aren't, in fact, very many secrets?

OPPENHEIMER: There aren 't secrets about the world of nature. There are secrets about the thoughts and intentions of men. Sometimes they are secret because a man doesn't like to know what he's up to if he can avoid it. . . .