The story of Joan of Arc, the peasant girl whose religious visions altered the history of France, has been told often. And like so many stories in history, things do not end well for Joan. On May 30, 1431, after a lengthy and highly unusual trial process, Joan is bound to a wooden stake in the market square of Rouen. High above a crowd of spectators, crying “Jesus, Jesus, Jesus” she is consumed by flames.

What is remarkable about the trial of Joan of Arc, especially for a Medieval trial, is how thoroughly documented it is. Through Joan’s own words, and the pointed questions of her accusers, history comes alive as it never could for any other trial now nearly 700 years in the past.

We could begin our story in the village of Domremy, France, where Joan, in her father’s garden at the age of 13, Joan saw a light and first heard the voice of an angel. But instead, following the lead of Helen Castor in her fine book, Joan of Arc: A History, we will begin a decade earlier, in 1415.

France Divided

It seemed as though France and England had been fighting each other for as long as anyone could remember. The Hundred Years War had been going on for over seven decades. In the summer of 1415, King Henry V of England invaded France, hoping to reclaim a kingdom he said was rightfully his. After Henry’s army landed in Normandy and captured the port city of Harfleur, French authorities sounded the alarm. King Charles VI of France (who suffered from episodes of paranoia and derangement) and his 18-year-old son, the dauphin Louis, rushed to Normandy’s capitol of Rouen where preparations were made to block the progress of the English army along the banks of the river Somme.

Henry V

In the early morning of October 25, the battle began. The French had superior numbers. French men and horses attacked the English. Razor-tipped arrows rained down upon the charging French, cutting through breastplates and flesh. The survivors—many of them—impaled themselves on sharpened stakes that the English had been placed in front of the English archers. When two hours of fighting ended, many of the great military leaders of France lay dead or were captured. The English took their prizes of dukes and counts (including the influential Charles, duke of Orleans) to Calais. From there, they would go on to London, and become prisoners. That fall day, after the battle the English called “Agincourt,” France lay, as Helen Castor describes it, “in a field of blood.”

In fifteenth century Christendom, victories in battles were taken as signs that an army was waging a just war—that God was on their side. So King Henry concluded from the victory at Agincourt that his cause was just. He rightfully should rule over France by virtue of his ancestor, Edward III, having a French mother. (France saw Henry’s claim to the French throne as outrageous; claims through the female line lacked validity in their view.)

France itself, in 1415, found itself divided into two groups of countrymen, the Armagnacs (or "Orleanists") and the Burgundians, two factions of the French Royal family. Each side called the other “traitors” and could tick off a long list of wrongs committed by the other side. In fact, France was experiencing a civil war. Henry V undoubtedly understood that the civil war made it an opportune time for his invasion. The division among the French traced back to the murder by John, the duke of Burgundy of his cousin, Louis, the duke of Orleans in 1407, after a power struggle for influence with the king. Although they could unite to fight against their mutual invading enemy, the English, any sense of unity would be fleeting.

Within a month after the battle of Agincourt, the Duke of Burgundy fixed his efforts on taking control of the government of France, which remained largely in Armagnac hands as it controlled Paris and with it the king. In July 1416, the Duke of Burgundy entered into an agreement with King Henry. Neither side would make war against each other in the northern territories of France that lay under Burgundian control.

Unfortunately for the Burgundians, a couple of royal deaths by 1417 made the new heir to the throne of France the king’s youngest son, 14-year-old Charles, a boy who was betrothed at the time to a young woman whose father was counted among the Armagnacs closest confederates. Charles’s mother, however, had fallen out of favor with the Armagnacs and had been exiled in Tours. So when the Burgundians captured Tours, they could claim authority to the throne of France through the queen, who they said spoke for her husband the king. In short, France was a country with two governments, one Armagnac-controlled and one run by Burgundians.

King Charles VI of France

Over the next couple of years, things went from bad to worse. Henry returned to France with an army that swept inland from the coast. Burgundians managed to make it through the gates of Paris and seize the royal residence of the king. Bloody fighting between Burgundians and Armagnacs in Paris left corpses stacked “like sides of bacon,” blood streaming into the city’s gutters. Buildings were set on fire. Within a month, the Burgundians brought the exiled Queen Isabeau back to Paris.

The only consolation for the Armagnacs was their success in getting 15-year-old Charles, son of the king and heir to the throne, out of Paris—the dauphin still wearing his night clothes as they fled the city. The Armagnac loyalists set up a new capital in Bourges, 100 miles to the south of Paris.

Duke John the Fearless of Burgundy

The English, meanwhile, had took Rouen and marched towards Paris from the west. With the English only 20 miles from Paris, and in September 1419 a meeting was arranged between John the Fearless of Burgundy and the dauphin Charles. The meeting was set to take place at Montereau, on a bridge that spanned a river separating Burgundian and Armagnac held land. With only ten men each accompanying them, and after swearing oaths to not harm each other, the men faced each other in a wooden building constructed just for the meeting on the bridge. But when John of Burgundy knelt before his prince, a axe was driven into his skull. With the assassination of the duke, any hope of a reconciliation between Burgundians and Armagnac supporters was lost. To the Burgundians, the dauphin Charles was a murderer and they could never owe him their allegiance. As between the dauphin and King Henry V of England, the Burgundians chose Henry—it was no longer a matter for debate.

In 1420, England and Burgundian-controlled France sealed a treaty. At the altar of the cathedral of Troyes, Charles recognized Henry as the rightful heir to his throne. Power over France’s government shifted to Henry’s control. Now, Charles and Henry, his heir and regent of France, could together get rid of the dauphin and those pesky Armagnacs—or so it seemed.

Endless War

The Burgundians held a trial—of sorts—of the dauphin in January 1421. The dauphin, of course, failed to appear to answer the charges against him, including the murder of John of Burgundy. But he was found guilty, disinherited from the crown, and sentenced to exile from the realm.

The following year saw a series of battles and skirmishes between the English and Burgundian forces and the Armagnac rebels. As the fighting waged, lives went on and lives ended. The dauphin married in 1422, and within months the dauphine was pregnant. That same year, King Henry died and was buried in Westminster. So did King Charles, at his royal residence outside of Paris. The deaths made Henry’s nine-month-old son (and grandson of Charles), Henry VI, the new king of France and England—or so he was proclaimed in London. Babies cannot run kingdoms, and so in France Henry’s brother, John the duke of Bedford, was named regent. For the dauphin, the death of his father, King Charles VI, meant something else: at that moment, he became Charles VII, the rightful new king of France. Burgundians and other detractors took to calling him “Charles, the Ill-Advised.”

In French practice, the coronation of a king could only happen with a sacred rite, involving anointing the new king with the sacred oil of Clovis, at the cathedral at Reims. The Holy Ampulla was housed there, eighty miles northeast of Paris. Getting to Reims meant travelling through hostile territory. The trip seemed impossible.

The fighting dragged on between the France of the north, ruled from Rouen by the regent Bedford, and the France of the south, ruled from Bourges by Charles. The natural boundary between the two Frances was the river Loire. In the fall of 1428, the Armagnac-controlled city of Orleans, the northernmost town along the river Loire, came under siege. Taking Orleans would mean for the English a gateway into Armagnac France. The siege went on for months and, for historian Helen Castor, “seemed to encapsulate the plight of the whole kingdom,” one of “scorched earth, torched homes, and lives and livelihoods destroyed.” To the extent either side had any momentum, it belonged to the English. In early February of 1429, they won a major battle near the village of Rouvray, thirteen miles from Orleans. The battle left over 400 Armagnac soldiers dead and reopened supply lines to English soldiers mounting the siege of Orleans.

Joan of Arc to the Rescue

The previous year, a young maid of about 16 years of age showed up in the Armagnac-controlled town of Vaucouleurs. The maid, of course, would become known as Joan of Arc. Joan told the captain of the garrison that God had spoken to her and that she needed to share her message with the dauphin. At first she was sent away, but Joan came back. On the second trip, in January 1429, the duke of Lorraine agreed to listen to her story. Her story had spread and people were open to a visionary who could give hope of a way out of their current quagmire. Town inhabitants chipped in and provided a horse, riding clothes, and an escort to allow Joan to undertake the perilous 270-mile journey through Burgundian-held lands from Vaucoulers to the royal court in Chinon.

The Castle of Chinon

The eleven-day trip west to Chinon could hardly have happened without the backing of Charles’s mother-in-law, Yolande of Aragon, a believer both in visionaries and in the dream of reuniting France under the kingship of Charles. What Joan told Charles’s key counselors was this: if given the money and the opportunity, God had told her she had the power to oust the English from France and secure the coronation of Charles in Reims.

The king and his court were intrigued. Put could Joan’s vision be trusted? They put the question to leading Armagnac theologians. The first step was to test her virginity, because virgins—or so it was believed—were less likely to be recruited by the Devil. A private examination by two women confirmed her virginity. Questioned about her faith and behavior by clerics, Joan appeared to be both a devout and a model of integrity. But still there were concerns, especially given her youth. Joan was moved to a town forty miles away and subjected to three more weeks of questioning under the leadership of the king’s chancellor. Joan handled the process well. The clerics found “no evil in her” but rather only “goodness, humility, virginity, piety, and integrity.”

In the end, it was decided that the best way to test Joan’s claim was to charge her with the mission of relieving the English siege of Orleans. If she—against all odds—succeeded, that would be strong evidence that God had spoken to her as she claimed. If she failed—well, nice try. It was a practical test. The clerics suggested that the king provide an escort for Joan to Orleans, “placing his faith in God.”

Before setting off on her mission, Joan dictated a letter to Henry and his regent. She demanded the return of “the keys of all the fine towns that you have taken and violated in France.” If he did not, Joan warned, she will make his men “leave,…and if they will not obey, I will have them all killed. I am sent here by God, the king of heaven, to face you head to head and drive you from all of France.”

Joan was outfitted with a custom-made suit of armor, presented with a specially prepared banner with the golden fleurs-de-lis France sown on a white background. She carried a holy sword and rode a topnotch horse given to her by the duke of Alencon. On April 26, 1429, Joan rode into battle. She was joined by soldiers that Joan had insisted first take confession and promise neither to pillage, rape, nor engage in prostitution. On May 4, she sent a message on an arrow to soldiers in the English encampment warning that unless they ended their siege she would “make a war cry that will be remembered forever.” She signed “Jeanne la Pucelle” (Joan the Maid). The English soldiers announced the arrival of the message-bearing arrow: “News from the Armagnac whore!”

Depiction of Joan leading the assault of Orleans

It took four days, and Joan received a superficial wound from an English arrow, but Orleans was freed. The half-year-long siege was over. The powers-that-be took it as a sure sign that Joan—and France—had God on their side. Joan went on to rack up other victories. Her acclaim spread. Even Burgundians were impressed. One knight wrote, “By the renown of Joan the Maid the hearts of the English were greatly changed and weakened.”

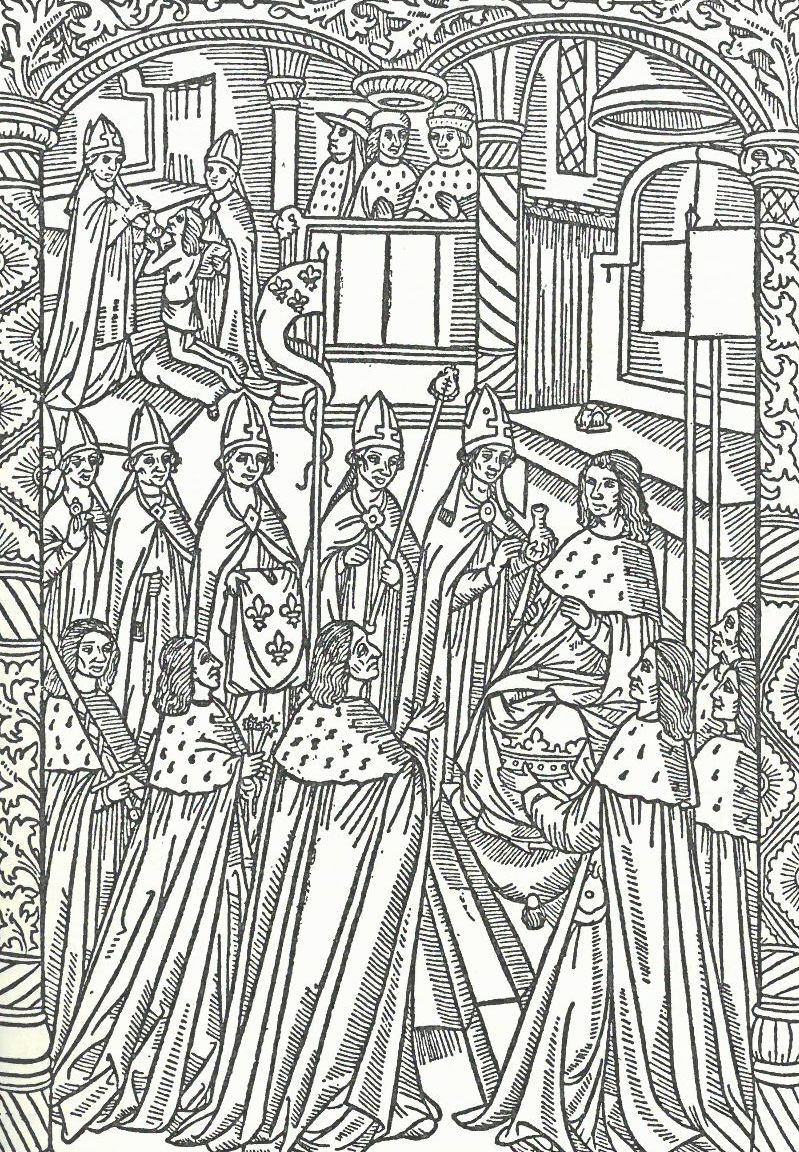

The coronation of King Charles VII at Reims

But Joan’s larger mission was to coronate Charles and then reunite France under his leadership. At the end of June 1429, the king set out with a royal party and an army that numbered in the thousands for Reims, site of the holy oil deemed essential to his coronation. With the now almost mystical Joan causing enemy-controlled city gates to open along the way, Charles made it to Reims. And on July 17, holy oil was placed on his head, shoulders, chest, and arms. The archbishop positioned the crown on Charles’s head to cries and trumpet sounds. Joan knelt before her king and wept. “Noble king, God’s will is done,” she said.

Captured

Joan’s reversal of fortune began in September 1429, just outside of Paris. Urging her men on in an assault on the walls of France’s largest city, she was hit in the thigh with a crossbow bolt. Her men were no match for the barrage of arrows fired from above, and they were forced to retreat. Joan was lifted from a ditch and carried to safety. The assault’s failure raised a question: if Joan was really God’s chosen warrior, why couldn’t she take Paris? When she again was well enough to lead men into battle, Joan chomped at the bit. She wanted a smashing victory to show skeptics she still had God on her side.

Meanwhile, perhaps in response to the crowning of Charles in Reims, the duke of Bedford decided it was time that young Henry (he was only 8 years old) receive his crown in Westminster Abbey, with plans made for a second coronation in France.

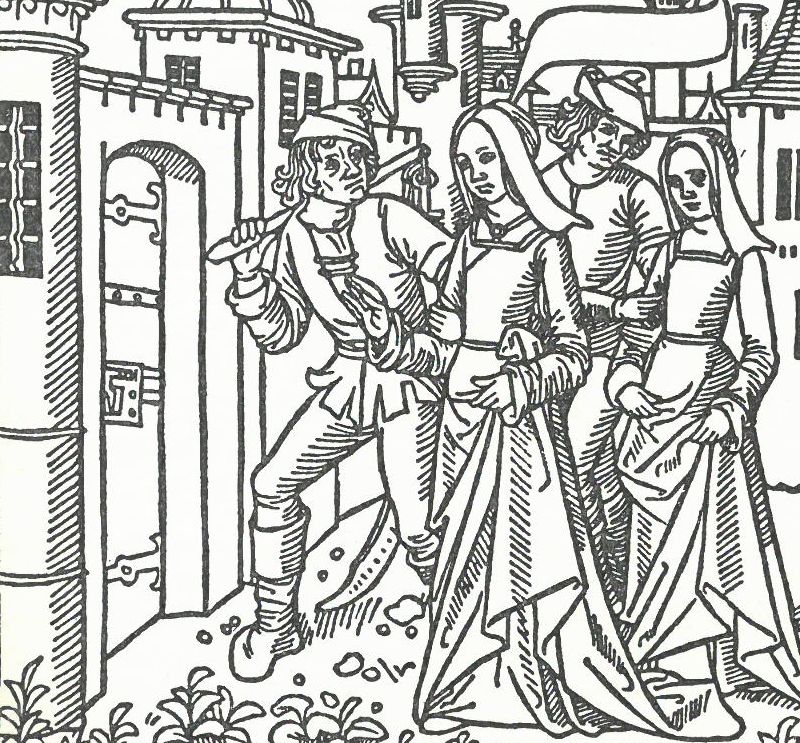

Depiction of the capture of Joan at Compiegne

In May 1430, Joan was focused on the town of Compiegne and relieving it from a Burgundian siege. Joan ordered a nighttime attack. She rode across the bridge and straight into the heart of the enemy’s position. But then another group of Burgundian and English soldiers moved in behind her, cutting her off from the bridge and possible safety. The city gates closed behind her, Joan found herself surrounded and was captured. Duke Phillip, leader of the Burgundians, was mightily pleased. He wrote that the capture “will demonstrate the error and foolish credulity of all those who have let themselves be convinced by the deeds of this woman.”

Captured Joan is led to Rouen

Under the laws of war, Joan was technically a prisoner of Jean de Luxembourg, commander of the Burgundian forces who made the capture. Joan was taken to a castle twenty miles away to await a decision as to what should be done with her. Three days later, theologians of the University of Paris and the vicar-general of the faith asked the Duke of Burgundy to surrender Joan to them, so that they might try her in an ecclesiastical court for various alleged crimes against God. But the theologians got no answer. Jean of Luxembourg was hoping to win a ransom for his famous prisoner.

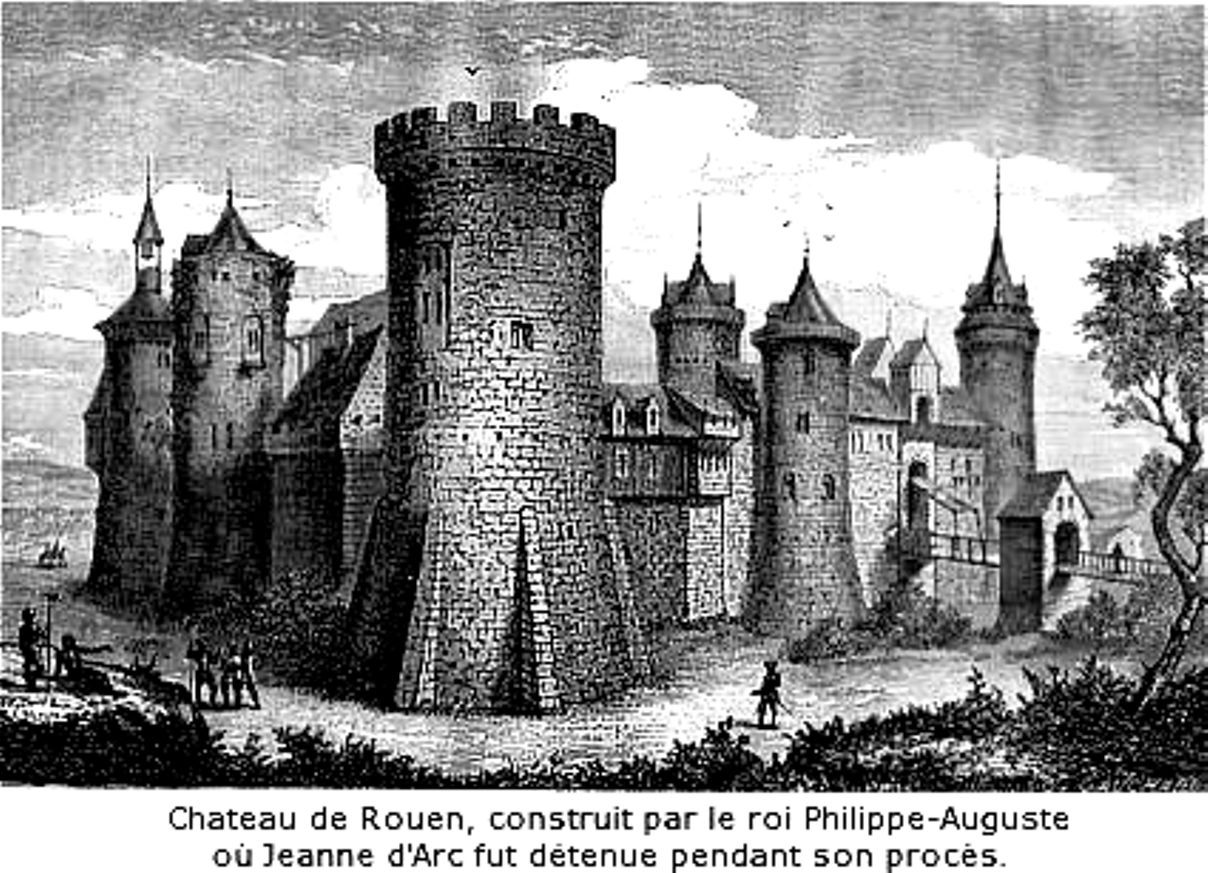

Eventually, Jean got his price for his prize. The king’s council, on behalf of King Henry VI, bought Joan from her Burgundian captors in November. They moved Joan to Rouen, the capital of English Normandy. On January 3, 1431, young King Henry (or, more accurately, his key advisors) issued an edict charging Joan with a long list religious crimes and ordering officers to deliver her to the bishop of Beauvais. She would be tried by Church authorities, but still held prisoner each night in the royal castle.

The charges listed in the edict included wearing men’s clothes, in violation of a prohibition found in the Book of Deuteronomy, falsely leading people to believe she was sent by God, and murder.

The Trial

At eight o’clock on the morning of February 21, 1431 executor Jean Massieu led Joan into the royal fortress. There she would meet Bishop Pierre Cauchon and 42 clerics. In the preceding weeks, Cauchon and his advisors had reviewed the evidence, created a list of articles of accusation, and prepared a series of question they intended to ask the defendant. Joan appeared dressed in male clothing, with her dark hair cut short. Prior to her appearance, she had again been examined and found to be a virgin.

The proceeding was to begin with Joan touching the Bible and taking a sacred oath to tell the truth. But Joan hesitated. “I don’t know what you wish to ask me. Perhaps you might ask me things I cannot tell you.” Bishop Cauchon pressed her, but Joan insisted that though she would gladly answer questions about what she had done, she could not reveal her revelations from God—even if she were to be threatened with beheading. Finally, Joan knelt and took an oath agreeing to tell the truth about her faith and her doings—but making no promise to reveal those messages God did not mean for her to share with anyone but her king, Charles.

Questions about her background were asked, and Joan answered. She was 19, from the village of Domremy. Her father was Jacques d’Arc, her mother Isabelle. She was baptized into the Catholic faith. Before returning her to her cell, Cauchon warned Joan not to attempt an escape, as she had once before, jumping from her tower cell.

In the interrogation of the following day, Joan answered questions about her letter to the English at Orleans, her assault on Paris, and other military actions. She also, despite her protest of the previous day, spoke of the messages she had received from God. The first, she said, came at age 13 in her father’s garden, the voice of an angel, telling her to be good and to go to church. She also testified that a voice from God had revealed her king to her when she arrived at Chinon. The “voice” or “voices” were also the subject of questions the next day. Joan said she had heard the voice that very day, telling her to answer boldly. Joan also had a warning for her questioner, “You say that you are my judge. Take care what you do, for in truth I am sent by God, and you put yourself in grave danger.” Asked how she knew for certain she was in God’s grace, Joan said, “If I’m not, may God put me there; and if I am, may God keep me in it. I would be the most wretched person in the world if I knew I were not in the grace of God.” The last question of the day concerned her practice of wearing male clothing. Asked if she wanted a woman’s dress, Joan said, “If you will let me, give me one, and I will take it and go. Otherwise, I’m content with this, since it pleases God that I wear it.”

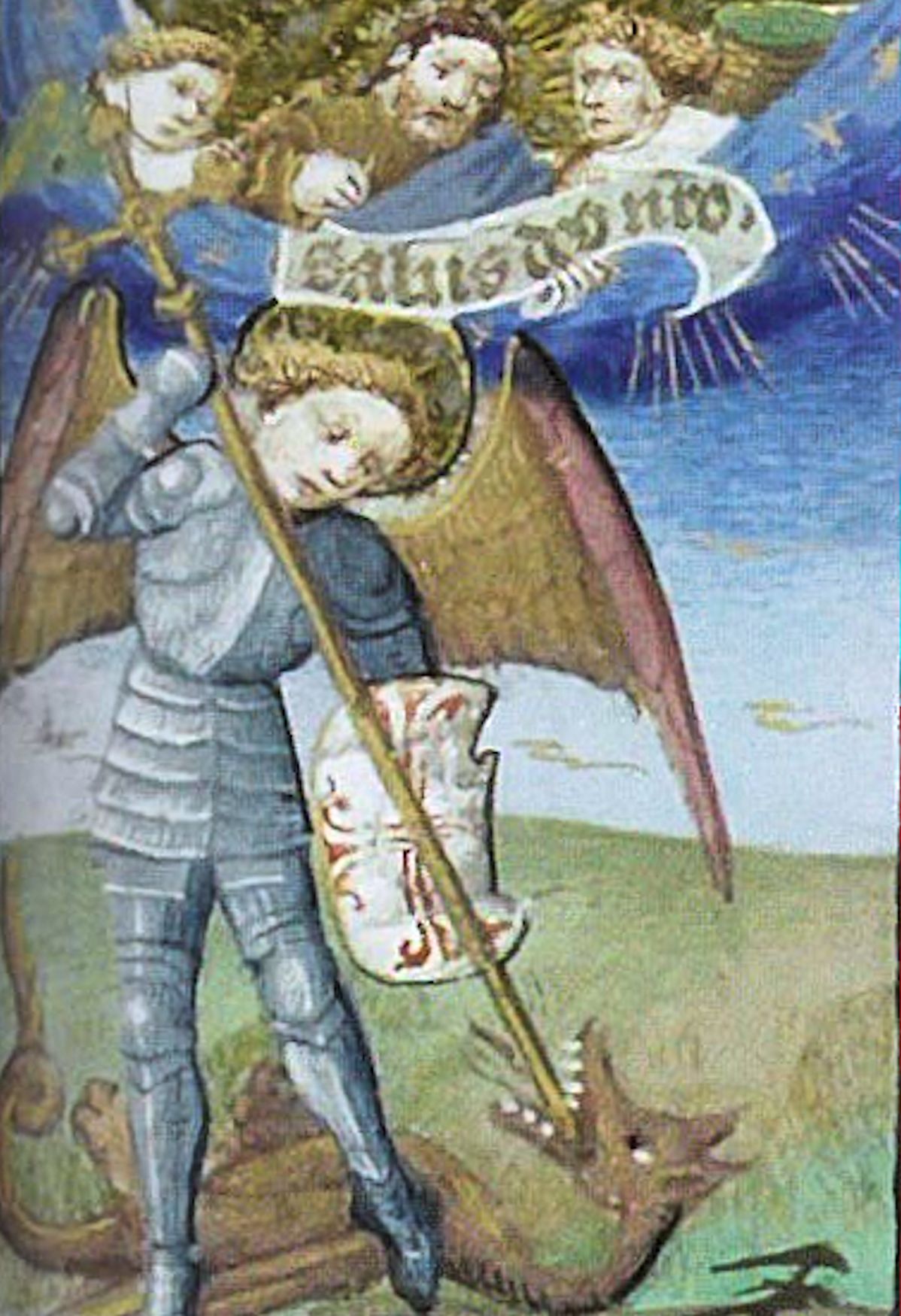

Saint Michael

In her third interrogation session, Joan revealed that the voices she heard were those of St. Catherine and St. Margaret. She told those in the assembly that on their forms were jeweled crowns. She had also heard from St. Michael—and saw the saints and the angels as real physical presences. “I saw them with my bodily eyes, just as well as I see you. When they left me, I wept and truly wished they had taken me with them.”

She also said that she carried a banner so as to avoid killing anyone in battle herself. She never used her precious sword.

After a final round of questions, Bishop Cauchon announced that Joan’s answers would be studied. If necessary, more questions would be answered later. And sure enough, a week later, Bishop Cauchon and seven other inquisitors visited her in her royal cell. The main focus of the questions was the specific sign she had produced for Charles to convince him that she was indeed sent by God. Joan first revealed that the sign could last for a thousand or more years and at that moment lay in the king’s treasury. It was brought to the kind by an angel, but she could say no more about it. Finally, the following day, she said the sign was a beautiful crown of pure gold. The angel, surrounded by many others of his kind, bowed before Charles and said, “Sire, here is your sign. Take it.”

At the end of the final interrogation, Joan was asked if she would submit to the decision of the Church on the question of whether she had committed mortal sins. She said she would submit to God—that “God and the Church are one and the same, and there should be no difficulty about that. Why do you make this difficulty?”

The next step was to draft formal articles of accusation based on Joan’s testimony. An original list of seventy articles was produced, but that was deemed too many. The seventy were, over the course of a few days, boiled down to twelve. The subjects covered in the twelve accusations included her visions, the "sign" she gave to Charles that she was sent by God, her confidence in the advice of angels and saints, her predictions of future events, her wearing of men's dress, her tactics in war, her leaving of her parent's home without their consent, her leap from a forty-foot high prison cell, her assurance that she would go to Heaven, her assertion that God supported the French against the English, her vow of virginity to angels and saints without counsel of a priest, and her unwillingness to submit to Church authority, The three issues most pressed in questioning were her alleged visions, her refusal to obey the Church, and her practice of wearing male clothing.

The days awaiting trial were not pleasant for Joan. She was seriously ill some of the time; at other times she had to cope with a pawing, taunting guard. Joan feared she might be dying and begged that she might be given the sacrament and buried on sacred ground. Only if she submitted to the Church, the bishop answered.

On May 2, weary though she was, Joan faced her judges in a room near the great hall of the castle of Rouen. Things began with a lecture in which Joan was told that although the Church had “tried the best we can to lead her back to the path of knowledge and truth,” the “wiles of the devil have triumphed.” Jean de Chatilllon, an old master of theology, explained to Joan the errors of her ways and beliefs. She had, he said, worn men’s clothes in violation of God’s commandment in Deuteronomy, she had made false claims about her revelations, and invented a story about an angel presenting a crown to Charles. She had, despite the best efforts of those concerned about her soul, stubbornly refused to admit her sins. Did she understand that while the Church would never take a life, it could turn her over to secular arm which could punish her with fire?

Joan answered, “If I saw the fire, I would say all that I am saying to you now, and would not act differently.” She added a warning: if the Church did allow her to be put to death, “evil will seize upon you, body and soul.” The defiant Joan was led back to her cell.

A week later Joan was brought to the great tower in the castle of Rouen. This time she was threatened with torture. She was shown the instruments of torture ready to aid in straightening her thinking. Officers were standing by ready to use them. Joan was unmoved: “In truth, if you tear my limbs apart and separate my soul from my body, I still won’t tell you anything else. And if I tell you anything, later I will say that you forced it out of me.” The judges decided against applying torture.

The culmination of the trial in a room close to her prison. Bishop Cauchon presided, but was joined by his vice-inquisitor, theologians and priests. Cauchon told Joan that in the two weeks since their last session, the theologians of Paris had weighed in on her case. With the benefit of their insights, the decision in her case was announced by the theologian Pierre Maurice. He went through the articles of accusation one by one, showing Joan’s errors. Her visions were either made up or diabolical in nature. The story about the angel bringing a crown to Charles was “not plausible,” her believe that she could foretell the future was pure superstition, her jump from her tower cell showed her willingness to commit the sin of suicide, her wearing of men’s clothes was blasphemy. The list went on, none worse than her refusal to submit to the judgement of the Church.

Even now, “at the end of your trial,” the theologian asked Joan to “think carefully about what has been said” and save her soul. Joan replied, “As for my words and deeds that I spoke of in the trial, I refer to them and wish to stand by them.” Bishop Cauchon declared an end to the trial and announced that Joan would be sentenced the next day.

The next morning Joan was escorted to an abbey in the center of Rouen. She saw a scaffold erected in a nearby open space. Henry Beaufort, the Cardinal of England, was there. Joan heard once again a familiar plea, submit to the Church’s judgement and admit your sins. This time Joan had a new answer. Yes, she would submit, but only if the conclusions reached in her case were affirmed by none other than the Holy Father in Rome. The gathered authorities were in no mood to accept this challenge to their authority. The pope was too far away; they spoke for the Church. Bishop Cauchon said that Joan’s obstinacy left him no choice but to turn her over to the secular authorities for punishment.

Then Joan began to speak. She would obey the Church after all. She would submit. Members of the crowd began to shout. There was confusion. But then Bishop Cauchon asked the executor of the court to present to Joan a statement of abjuration, which he read to her. Joan agreed to renounce her crimes and she marked the document with a quill. Cauchon announced that Joan would be welcomed back to the Church, her soul would be saved—but she would live the rest of her days in prison in penance for her sins. Joan was escorted away, given a dress to wear, and her hair was shaved.

But Joan’s imprisonment would not last a lifetime—only four days. The call came to Bishop Cauchon on May 28 that he should come to Joan’s cell. Joan, once again, was dressed in men’s clothes, not the dress she had been given after her abjuration. Joan explained that she did not understand she had promised not to wear men’s clothes and that they were more practical living as she did among men. Besides, she thought that wearing a dress meant she could attend mass—but that had not happened. Move me to a better prison, among females, and allow me to attend mass—if that could be promised, she would gladly put her dress back on. But Cauchon and the judges were in no mood to bargain.

Especially so after Joan informed them that voices had told her she had damned her so in making her abjuration. She took back everything she had said at the scaffold.

Cauchon and the judges left to discuss their next action. Meeting the next day with forty or so clerics, the conclusion was made that Joan was a relapsed heretic—and there was only one thing to do with relapsed heretics.

The next morning, in her cell, Joan was asked for a final time whether she truly had seen visions. Yes, she said. “Whether they are good spirits or evil spirits, they appeared to me.” Did an angel really carry a crown to Charles? No, there was no angel—the crown was the promise to lead Charles to his coronation and it was brought by her. Bishop Cauchon signaled for a friar to come to hear Joan’s confession and administer the Eucharist.

Joan was led to a cart and taken through Rouen’s streets. She wore a cap with the words “relapsed heretic, apostate, idolater.” By the pyre and platform that had been built in the market square, Bishop Cauchon read her list of sins. Like the dog in the Book of Proverbs that returned to her vomit, she returned to her sins and must be separated from the Church and turned over to secular power.

Joan was bound to the wooden stake. She prayed until the fire did its work. After her last breath, with her clothes burnt off completely, the executioner raked back the fire so the crowd could see she was indeed a woman. Then he again stoked the fire until all that remained of Joan of Arc were her ashes. They were tossed into the Seine.

Aftermath and Analysis

Once Jean made clear to her captors that she believed it was God’s will that the French drive the English out of France, she was doomed. The only real question was whether her ultimate punishment would be death; that choice would be Joan’s. Joan represented a challenge to the legitimacy of the English-Burgundian regime, and authorities would never tolerate such a challenge.

But political fortunes change and so would Joan’s—at least with respect to the validity of the judgement against her. In 1435, the Duke of Burgundy and King Charles signed the Treaty of Arras in which the Burgundians were granted territorial concessions and restitution for the murder of the duke’s father in return for Duke Phillip recognizing King Charles as his sovereign lord. The treaty changed everything. In 1437, King Charles was welcomed into Paris, a city he had last seen at age 15. The English were on the run. There would be short-lived truces, but the inevitable came in 1450, when the last English holdout in France, the fortress of Cherbourg, was abandoned.

The year the last English soldiers were driven from France was also the first time in years King Charles spoke publicly of Joan. In his statement, the king said Joan had tried by our enemy “that had great hatred against her” and that she “had been put to death very cruelly, iniquitously and against reason.” He asked a theologian, Guillaume Bouille, to look into the matter.

Bouille interviewed persons who had participated in the trial nineteen years earlier. He found witnesses who said that Bishop Cauchon took orders from the English and that English pressure caused the denial of an appeal to the pope. More damning, one witness who should know said Cauchon sent a spy to Joan—a spy who suggested he had Armagnac sympathies and acted as her confessor and counsellor while she was in prison. While the spy and Joan talked, the witness said, officials listened in a nearby room through a secret hole. Another witness reported that Joan’s relapse was met with celebration, Cauchon declaring, “Farewell it is done!” (Although later another witness would report that Cauchon became angry when an English cleric criticized him for accepting Joan’s abjuration, telling his critic that it was his job to save souls, not kill people.)

There was also testimony that Joan had been sexually assaulted by guards. She had earlier experience with lustful men. A nobleman, testifying years later on Joan’s behalf, recalled that when he encountered Joan shortly after her capture he had grabbed at her breasts and tried to put his hands up her clothes. The fight she put up against him, he testified, was proof of her virtue.

Three witnesses to Joan’s execution described how impressed they were with Joan’s piety, even as the flames swept up around her. Almost everyone present—including Cardinal Beaufort—wept as they heard her call to Christ and his saints. Two of the witnesses claimed to have dashed off and grabbed a crucifix to hold before Joan until she became blinded by the flames.

The investigation into Joan’s trial stalled for a while as various political difficulties worked themselves out, but eventually a list of articles by which Joan’s trial might be condemned were drawn up. The document noted the prejudice of the English against Joan, threats by the English against various trial participants, the denial to Joan of any legal advice, and the length and difficulty of her interrogations.

In June 1455, Pope Calixtus II issued a papal declaration authorizing a new trial, to be overseen by three papal commissioners, and with Joan’s surviving family as plaintiffs. The proceeding opened on November 7, 1455 before a great crowd in the Cathedral of Notre-Dame in Paris. Venue shifted later to the episcopal court of Paris where commissioners listened to stories of Joan’s early life—spinning with her mother, ploughing fields, tending animals, falling to the ground to pray whenever she heard church bells. They heard battlefield stories of Joan’s insistence that her soldiers not pillage, plunder, consort with prostitutes, or even swear. Other witnesses argued that Joan’s battlefield successes proved the truth of her visions, and that near miraculous things seemed to happen when Joan was around (winds suddenly becoming favorable; water rising to float their boats).

The verdict came as no surprise, when it finally did on July 7, 1456. The judges declared that the twelve articles on which Joan was condemned were drafted “corruptly, deceitfully, slanderously, fraudulently, and maliciously.” Joan’s sentence was null and void. Moreover, a cross should be erected at the spot in Rouen where she died.

But Joan’s story was not yet over. In May 1920, before a large crowd gathered outside St. Peter’s Basilica, the Roman Catholic Church declared Joan of Arc to be a saint. The feast day of St. Joan is May 30, the day of her execution.

Helen Castor concludes her biography of Joan by suggesting that over the centuries "this ferocious champion of one side in a complex and bloody war has been robbed of her context and her roaring voice." She might not have been God's agent, she might not have deserved to have been made a saint, but she led a wholly remarkable life.