The Trial of Amanda Knox (2009): An Account

by Douglas O. Linder (2020)

It was supposed to be a year of growth, learning and exploration. Amanda Knox hoped to experience the world beyond her middle-class West Seattle neighborhood and learn Italian. She also considered her prior sexual experience limited—four guys, all in committed relationships—and wanted to change that. For her year abroad, she wanted, she wrote later, “sex to be about empowerment and pleasure.” But what, for Amanda, was supposed to be a dream year studying at the University for Foreigners in Perugia, Italy, turned into a nightmare.

When Amanda’s British roommate, Meredith Kercher, was discovered brutally murdered, Italian authorities leapt to the unlikely conclusion that Amanda, her Italian boyfriend, and a third person barely known to Amanda, committed the crime as the result of a sex game gone horribly wrong. For the press, from Italy to Britain to America and beyond, it was a story too good to pass up.

The Amanda Knox trial reveals problems with the Italian justice system, but it reveals much more than that. It is a fascinating study of how people steeped in one culture can draw mistaken conclusions about the behavior of someone from a different culture. In addition, the Amanda Knox trial once again shows how miscarriages of justice can occur when authorities focus on a suspect—how confirmation bias can make innocent acts of that person seem incriminatory and send common sense flying out the window.

From Seattle to Perugia

Amanda, in her own words, began her high school career at Seattle Prep as “the quirky kid who hung out with the sulky manga-readers, the ostracized gay kids, and the theater geeks” and ended it as something of a soccer jock known for her blunt manner and general “kookiness.” A friend described her as goofy, naïve, and trusting. In college, at the University of Washington, her friends were mostly “off-beat” and male. She date “a Mohawked, kilt-wearing, outdoorsy student named DJ.” She described herself as a hippie, enjoyed rock climbing, hiking, yoga, and theater. She made the Dean’s list while working as a barista and as an art gallery receptionist. Her closest college friend, Madison Paxton, said Amanda could sometimes “be loud and offensive,” but at the same time was always “non-confrontational.’

Amanda’s parents, Edda and Curt, divorced when she and her sister, Deanna, were young. Amanda announced her decision to spend a year abroad in Italy at a rare two-parent lunch in April 2007. She expected her free-spirited and remarried mother to be on board, her more “linear thinking” and practical father she was less sure of. But both agreed to Amanda’s proposal and the planning began.

Finding a place to stay for the year in Perugia turned out to be a surprisingly easy decision. She fell in love with and agreed to rent the first place she checked out, an upstairs bedroom in a two-level stone, 300-year-old villa on top of a hill and close to the university. The villa at No. 7, Via della Pergola was occupied by a number of other young people, both male and female. Men lived on the basement level, while two Italian women, Laura and Filomena, roomed together on the upper level. Space for one additional woman remained unrented. Amanda’s initial reaction was that the villa “felt like a happy place.” As satisfied as Amanda was with her new lodgings, it was located close to a seedy urban piazza frequented by drug dealers.

Shortly after renting the room in Perugia, while traveling with her sister in Germany, Amanda learned the name of a new roommate: Meredith Kercher, a British exchange student. Amanda and Meredith met for the first time on September 20, 2007, when she moved to Perugia. Although Amanda considered her “more mainstream and demure” than she’d ever be, the two seemed to hit it off. Amanda said she liked Meredith a lot. Meredith was attractive, smart, and a bit of a perfectionist.

Meredith Kercher

Amanda and Meredith got along well and never argued. They attended events together, smoked hash and pot together, and went out for pizza together. According to Amanda, the two has an “easy togetherness.” But Meredith, who was in Perugia studying political theory and the history of cinema, had her own circle of girlfriends from the U.K. and did most of her partying with them.

In Perugia, Amanda rose early to run through a series of yoga poses and strum her guitar. She’d walk to her 9:00 a.m. Italian class, taking a seat in the front row. But she clearly enjoyed the laid-back style of the country. She rose to morning yoga sessions and some guitar strumming. Writing on her “Foxy Knoxy” (a name she said she was given because of her skills on the junior high soccer field) Myspace page, she posted a naked picture of a Italian man (“Federico”) who she met on a train and ended up in bed with, talked about smoking pot, and praised Italy’s three-hour lunch breaks: “Having all that time in the middle of the day reminds you that life isn’t all about going to work and making money.”

Amanda entered into a short-term relationship with a young man, nicknamed Juve, whose job it was to hand out flyers for a newly opened pub called Le Chic. Juve encouraged Amanda to apply for a job at the pub, and encouraged his boss, an Italian originally from the Congo named Patrick Lumumba, to hire her. Lumumba agreed, offering Amanda five euros an hour to wait and clean tables, but mainly to attract male customers.

Downstairs in the villa, the party never seemed to end. Young people came and went, joints were smoked, wine was drunk, and music played. One night one of the downstairs visited was a lanky, basketball-playing black Italian, originally from the Ivory Coast, who people called “the Baron.” His real name was Rudy Guede. Rudy ended up drunk and sleeping on a toilet full of unflushed feces. He came back to the villa a week later to watch a Formula One race on television.

Rudy Guede

Rudy had first noticed Amanda at the Le Chic pub. Rudy later said he was very attracted to Amanda, writing in a letter “going to bed with her, yes,” that was “the goal.” He also desired Meredith. “Damn, she was beautiful,” Rudy wrote.

On October 25, Amanda and Meredith decided to take in a performance of classical music. As the musicians warmed up, Amanda noticed a young brown-haired man wearing wire-rimmed glasses. They exchanged smiles. When Meredith left to meet friends at intermission, the young man took her seat. It would be a fateful decision. His name was Raffaele Sollecito. Raffaele was twenty-three and a virgin, a computer major, and the only son of a wealthy doctor. Raffaele would later say of Amanda, “It was love at first sight. I was attracted by her curious disposition and, of course, her beautiful teen appeal.” Amanda described Raffaele as “humble, thoughtful, and respectful”—as well as “nerdy and adorable.”

Later that night, the two walked together to Raffaele’s apartment where they shared a joint, where Amanda told Raffaele that he looked like Harry Potter, and where they had sex. After that evening, Amanda did not spend another night in her room in the villa on via della Pergola. They became, in Amanda’s words, “a thing.”

The Murder of Meredith Kercher

On November 1, 2007, Amanda left Raffaele’s apartment to spend a few hours to spend a few hours at her own place. Raffaele came over later, and the two were eating pasta when Meredith came out of her room, after taking a shower, and said that she was off to spend time with friends. “See you. Ciao,” she said as she headed out the front door. They were the last words the two roommates would ever exchange.

In the late afternoon, Amanda and Raffaele went back to Raffaele’s place. They decided to download Amanda’s “all-time favorite movie,” Amelie. About 8:30, Amanda realized that it was one of her regular worknights at Le Chic. Checking her phone, she was relieved to find a text from Patrick Lumumba telling her that, after the Halloween crowds the night before, he expected the night to be slow and she needn’t come in. Amanda texted back at 8:38, “Ci vediamo piu tardi bouno serata!” (“See you later. Have a good evening!”). Amanda turned off her phone, “just in case he changed his mind.” When the movie ended about 9:10, they ate a fish dinner, dealt with a leaky kitchen sink, and smoked a joint. Amanda, sitting in Raffaele’s lap, read aloud from a Harry Potter book. The couple had sex and went to sleep.

The next morning, Amanda walked back to her place and found nobody home. She noticed a smear of blood on the bathroom faucet. She took a shower before noticing what looked like more blood on a bath mat. Then she noticed feces in the toilet. None of her roommates, she knew, would leave a toilet unflushed. Something was wrong! Amanda grabbed her purse and ran out of the house.

She called her mother first, then her roommates. She called Filomena first and learned she had spent the night at a boyfriend’s, and that her other Italian roommate, Laura, was in Rome on business. She dialed Meredith’s number. No answer.

Amanda walked back to Raffaele’s and described the scene at her villa. Raffaele said they needed to go back and look around. Back inside, they gasped when they opened the door to Filomena’s room and found the window shattered and glass everywhere. The room was a mess, with clothes piled everywhere. They next tried opening the door to Meredith’s room, but it was locked. They went outside to see if they could peer into the room from an outside window, but getting a look inside proved impossible. They called the police.

Amanda and Raffaele Sollecito shortly after the discovery of Meredith's body

Raffaele and Amanda were hugging on the driveway when an officer from the Postal Police, a unit that deals with tech crimes, approached them. The officer reported that two cellphones (Meredith’s phones) had been found and turned into them that morning. Might they know anything about that?

Filomena arrived. Upon learning that Meredith’s door was locked, she began shouting at the police, demanding they break open the door. “She never locks her door!” Filomena said. The postal police resisted, saying it was outside their authority. But Filomena’s boyfriend, who arrived with her, succeeded in kicking the door open. What they saw was horrifying. “Everyone out of the house! Now!” shouted the police.

Inside the room, a foot poked out from Meredith’s comforter. The walls and floor were streaked in blood. Lifting the comforter, police saw Meredith’s body, naked from the waist down. A sliced off bra lay next to her body. Her T-shirt was saturated with blood. Her neck showed multiple and deep stab wounds.

The Investigation

In the afternoon, police questioned Amanda and Raffaele, separately. Police interviewed Amanda, first in Italian and then in English, for six hours. Although Amanda did not know it, police already considered both her and her boyfriend suspects, although their first working assumption was that the killer was probably someone Meredith met at a Halloween party the night before. But Amanda raised suspicion because they thought the break-in looked “staged.” They thought a killer who would cover a naked body with a blanket was most likely a female. Taking a shower in a blood-spattered bathroom made no sense. Finally, Amanda’s behavior—her kissing and hugging Raffaele—didn’t seem to them like the sort of grieving you’d expect from someone whose roommate had just been brutally murdered.

During a second day of questioning, Amanda fueled suspicion when she denied using marijuana, a lie told at the request of her roommate Laura, who feared the legal possible ramifications from such a revelation. She also raised eyebrows when, after slipping on booties and gloves during a return visit to the villa with police, she thrust her arms out “like the lead in a musical” and sang out, “Ta-da.” Later in the evening, she went on a brief shopping expedition with Raffaele. Denied access to her own underclothes, she settled on a pair of red bikini briefs. That too, would arouse the suspicion of investigators. Once investigators believe someone to be guilty, nearly any behavior out of the ordinary suddenly seems incriminatory.

Day four of questioning was the worst, the day police succeeded in coercing Amanda to make what would eventually be recognized as “a false confession.” It happened without a defense lawyer being present, without Amanda being informed of her right to remain silent. When officer Rita Ficarra showed up in the waiting room to greet Amanda, she was on the floor, legs splayed, in the process of doing a split. That too would strike investigators as evidence of guilt. The interview probed deeply into Amanda’s movements on the night of November 1, her male acquaintances in Perugia, her interaction with Kercher. They asked about exact times, about details she couldn’t remember. Eventually, according to her own account, “I started forgetting everything. My mind was spinning. I felt as if I was going totally blank.”

They insisted that she must have met Patrick Lumumba, her boss, later that night based on her 8:30 pm text to him that said, “See you later.” Americans would not understand that to be a literal plan, but the Italian meaning of those words is literal—they had agreed to meet later that night. When Amanda continued to assert that she never left Raffaele’s sometime after 8:30, the investigators called her a liar.

Police tactics can be rough. They falsely claimed that Raffaele had confessed that they had left his apartment. They told her, “You’re going to go to prison for thirty years if you don’t help us.” At one point, Rica Ficarra slapped Amanda on the back of her head, then hit her a second time above the ear. (Ficarra, not surprisingly, denied this.) To get her attention, Ficarra said. The investigation took its toll. In Amanda’s words, “I snapped.” When investigators insisted, “You know who killed Meredith,” she said, “Patrick—it’s Patrick.” Asked whether Patrick had sex with Meredith before he slashed her, Amanda said, “I guess so. I’m confused.”

At 1:45 am, Amanda signed “a confession” placing her at the murder scene and naming Patrick Lumumba as Meredith’s killer. The signing done, her investigators “whooped and high-fived.” A second “spontaneous declaration,” signed by Amanda a few hours later, included this sentence: “I do not remember if Meredith screamed or if I heard any thuds because I was in shock, but I could imagine what was going on.”

In the afternoon of the same day, Amanda would try to tell a different story, to say that what the signed statements said did not reflect her actual memories. But it was too late. Amanda was arrested. She would spend the next 1,427 nights in prison.

Raffaele Sollecito

Authorities charged Amanda, Raffaele, and Patrick Lumumba with the murder of Kercher. Amanda didn’t know she was charged with murder until her arraignment, three days after entering prison. Perugia’s chief of police told reporters, “The motive is sexual, very much so.” The media was all over the story, digging up social media images to fuel the story: pictures of a grinning Amanda holding a machine gun (taken at a World War II museum in Germany), Raffaele posing as a mad doctor dressed in white with a meat cleaver, Meredith in her Halloween vampire costume.

The police investigation would continue for a year, but the crux of the case against Knox and Sollecito was based on the four days of questioning after the murder. There was other “evidence,” but it would mostly turn out to be either fabrication or the result of shoddy police and lab work. A lab in Rome, for example, reported it found traces of both Amanda’s and Meredith’s DNA on a knife found in Raffaele’s apartment. The bra clasp found near Meredith’s body was said to have Raffaele’s DNA on it. Damning if true, but actually the result of contamination. Raffaele’s kitchen knife was said to be the murder weapon, but the cut on Meredith’s neck wasn’t deep enough for that too be the case. Police jumped to the conclusion that shoe prints in the murder room were Raffaele’s, when later and closer analysis made clear that they were not. A witness emerged to claim he saw Amanda, Raffaele, and Guede together on Halloween, but his credibility suffered a massive hit when he also said he saw Amanda and Raffaele together in August, two months before they met.

The villa at No. 7 Via della Pergola

The police were forced to revise their theory of the case on November 10, when none of the fingerprint samples taken in the murder room matched any of the three persons charged with murder. The prints did, however, match those of another man in the Perugia police files, Rudy Guede. Guede had taken a train out of Perugia the night of the murder. In a police-monitored Skype chat, authorities determined that Guede had fled to Germany. He was arrested in Mainz. When his Nike shoes were found to have a print that more exactly matched the bloody print in Meredith’s room than Raffaele’s, police dropped the murder charge against Patrick Lumumba and filed murder charges against Guede. Watching the release of Patrick, Amanda later wrote, “I felt an enormous emotional burden lift from my heart.”

One might think the arrest of Rudy Guede would cause authorities to reconsider their theory of the case. Wouldn’t a murder carried out single-handedly by Guede best match the known facts of the case? But no, authorities essentially decided to simply swap out Guede for Lumumba. The murder now was a result of a sex-game gone bad involving Knox, Sollecito, and Guede. Although Rudy had previously said “Amanda has nothing to do with it—she wasn’t there,” Guede now helped authorities by making a statement placing Amanda and Raffaele at the murder scene. Guede claimed “a fight over money” between Amanda and Meredith “sparked it off.”

The Trial of Amanda Knox and Raffaele Sollecito

The evidence of Guede’s guilt was overwhelming. The Kercher murder was a culmination of a recent series of break-ins by Guede and his DNA was everywhere. His lawyers requested an abbreviated trial, before only a judge with no live witnesses. Under this option provided by the Italian justice system, the maximum sentence is reduced by a third from the maximum available in a jury trial.

Guede after arrest

Pretrial proceedings for Amanda and Raffaele began on September 18, 2008, continued for five weeks, and were folded into Guede’s abbreviated trial. Judge Micheli found Guede guilty and sentenced him to thirty years (later reduced to sixteen) in prison. He then announced that he found sufficient evidence of guilt for Amanda and Raffaele to be tried for murder.

The full trial of Amanda Knox and Raffaele Sollecito opened in January 2009 in Perugia’s fifteenth-century courthouse, in a courtroom called the Hall of Frescoes. Amanda’s and Raffaele’s fate would be determined by two judges and six middle-aged jurors, all selected by computer, and all wearing red, green, and white sashes, the colors of Italy’s flag. The murder trial was combined with a civil trial slander brought against Amanda by Patrick Lumumba.

The two defendants, sitting with their respective lawyers, appeared a study in contrasts. Raffaele looked anxious and constantly gnawed his fingernails. Amanda, for the most part, seemed her breezy self, dressed in T-shirts, jeans, and sneakers, and smiling at almost everyone in the courtroom.

The Prosecution Case

With court sessions held only once or twice a week, the prosecution case alone lasted from January until June. Chief Prosecutor Giuliano Mignini called twenty witnesses to testify as to events on or around the night of November 1, 2007. An elderly woman testified that she heard a scream about 11:00 pm and then heard people running from the house. “It made my skin crawl,” she said. A homeless person claimed he saw Amanda and Raffaele near his bench on Piazza Grimana, which overlooks the villa, about 9:30 pm on the murder night. The owner of a grocery store testified she saw Amanda buying cleaning products, presumably used to clean the murder scene, on the morning of November 2.

Amanda Knox during her trial

In February, testimony turned to a focus on Amanda’s relationship with Meredith. Meredith’s British girlfriends testified that Meredith was annoyed by Amanda’s openness about sex and her not using a toilet brush. Robyn Butterworth testified that it “seemed strange” to Meredith that Amanda would openly display of condoms and a vibrator in the bathroom. The latter testimony prompted Amanda to make what Italian law calls “a spontaneous declaration.” Amanda rose to say, “The vibrator was a joke, a gift from a girlfriend before I arrived in Italy. It’s a little pink bunny about this long.” Amanda held up her thumb and index finger to demonstrate its length. Not all the witnesses testified there was significant tension between the two roommates. Filomena told the court that Amanda and Meredith got along just fine.

Next it was time for the prosecution’s forensic witnesses. Officer Monica Napoleoni testified that she concluded the break-in was staged because “there was glass on the windowsill, and if a stone came from the outside, the glass should have fallen below.” She described Amanda’s and Raffaele’s accounts as “too strange” to be probable. Officers denied any rough treatment during Amanda’s many hours of questioning. “No one hit her,” Rita Ficarra testified. She said she thought Amanda’s cartwheels and splits at the police station were “out of place.” The DNA evidence concerning knifes and bra clasps, touted so heavily by investigators, was fiercely—and most observers agreed, successfully—challenged by defense attorneys. The results of the DNA analysis seemed far from reliable, with contamination an equally likely explanation for the presence of DNA from Amanda or Raffaele.

The Defense Case

On June 12 and 13, the defense opened its case with its star witness: Amanda Knox herself. (Raffaele Sollecito did not testimony, with his lawyers concluding it was in his best interests to keep most of the focus on Knox.) Testimony from defendants, however, is often taken with a grain of salt—especially Italy, where they are not sworn in and generally are believed to be lying.

Amanda seemed assured on the stand and avoided falling into traps set by prosecutors. She did her best to explain her seemingly odd behavior of showering in a blood-spattered bathroom and how she came to make her accusation against Patrick Lumumba. She testified that she was slapped twice during her lengthy interrogation, demonstrating the force of the blow by dropping her head down and opening her mouth wide in surprise. Amanda testified, “They were yelling at me, and I only wanted to leave, and I was thinking about my mom, who was arriving soon.” After she finished her testimony, Amanda’s lawyer, Carlo Vedova told her, “Amanda, you nailed it.”

After a two-month summer break, the trial resumed with a parade of battling forensic experts. The defense was confident enough that the prosecution’s conclusions concerning the DNA evidence were unsupportable that it asked Judge Massei to order an independent review of the evidence. The judge denied the motion.

Closing Arguments and Verdict

In December, Prosecutor Giuliano Mignini gave the first closing argument. Mignini continued to insist the murder came about as a result of “an unstoppable game of sex and violence.” He painted a picture for jurors: “It’s easy to imagine Amanda, angry at the British girl for her increasing criticism of Amanda’s sexual easiness, reproaching [Meredith] for her reserve. Let’s try to imagine she insulted her. Perhaps she said, ‘You were a little saint. Now we’ll show you. Now you have no choice but to have sex!” Mignini continues, “The British girl was still on her knees. . . Rudy was to the left. Raffaele brought himself around behind her and tried to tear off her infamous bra clasp.” He carried his imagined scene to its bloody conclusion, allowing, “Obviously, it’s a hypothesis.”

After a closing argument by the co-prosecutor, there came what Knox described in her book Waiting to Be Heard as “the most surreal moment of my nightmarish trial.” The prosecution played a 3-D computer-generated animations featuring avatars representing Amanda, Raffaele, Rudy Guede, and Meredith, all dramatizing Mignini’s improbable hypothesis for the murder. When the show was over, co-prosecutor Manuela Comodi asked the jurors to give Amanda and Raffaele life imprisonment.

Patrick Lumumba’s civil attorney, Carlo Pucelli, went next. He told jurors that within Amanda “resides a double soul—the angelic and compassionate, gentle and naïve one” and “the satanic, diabolical Luciferina who was brought to engage in extreme, borderline acts.”

When the defense’s turn came, Raffaele’s lawyer, Giulia Bongiorno, spoke first. She said, “Amanda looked at the world with the eyes of Amelie [the heroine in Knox’s favorite movie]” He explained, “Amanda just sees things her way. She reacts differently. She’s not the classic Italian woman. She has a naïve perspective of life, or did when the events occurred. But just because he acted differently from other people doesn’t mean she killed someone.”

Amanda’s attorney, Carlo Vedova, told jurors, “There is a responsible party for this and it’s not Amanda Knox.” He concluded, “Condemning two innocents will not restore justice to poor Meredith’s memory, nor to her family. There’s only one thing to do in this case: acquit.”

Amanda was allowed to make a final plea. She said, “I’m scared to lose myself. I’m scared to be defined as what I am not and by acts that don’t belong to me. I’m afraid to have the mask of a murderer forced on my skin.” It was time to wait for the verdict.

Amanda Knox awaiting verdict in her trial for murder

At 11:00 pm on December 4, 2009, a guard came by Amanda’s cell at Capanne Prison. The verdict was ready to be delivered; it was time to go the court for a final time. At four minutes after midnight, a court bell rang and the judges and jurors filed in. Minutes later, Judge Massei announced the verdict. “Colpevole,” he said. Guilty. Both Knox and Sollecito were found guilty. Amanda moaned, repeating “No, no, no!” Some spectators cheered, while others booed. Knox was sentenced to twenty-six years in prison. Judge Massei’s 407-page report explaining the decision was released months later.

The Appeal

Prison affords an inmate lots of time to read, and Amanda read a lot. Appropriately, given her present situation, she read Franz Kafka—and other similar fare: Dostoyevsky’s The Possessed, Alexander Solzhenitsyn’s The First Circle, Marilynne Robinson’s Housekeeping.

Knox’s and Sollecito’s lawyers filed appeals. Unlike in the United States justice system, judges and juries decide appeals and can base their decisions not just on legal errors in the court below, but also on new evidence and additional testimony. Amanda’s appeal was considered from December 11, 2010 to June 29, 2011.

In her declaration to the court, Amanda said, “I am innocent. Raffaele is innocent. We did not kill Meredith. I beg you to truly consider that an enormous mistake has been made with regard to us.”

The first decision for the court was whether to accept review at all. For once, Amanda received a favorable decision. “I’m convinced the case is complex enough to warrant a review in the name of reasonable doubt,” Judge Claudio Hellmann announced.

Prosecution witnesses, in the appeal, came under new and heavier criticism and faced a more skeptical judge and jury. Independent experts offered their conclusions regarding the DNA evidence, and they concluded that contamination explained away most of what the prosecution saw as incriminating test results. Professor Carlo Vecchiotti told Judge Hellmann that the DNA sample from Kercher’s bra clasp was so poor and mixed that “I could find your DNA too.” Mario Alessi, a friend of Rudy Guede testified that Guede described to him in detail Kercher’s murder, which Guede said was carried out by himself and another friend. Alessi said Guede told his friend committed the actual murder, using a pocket knife with an ivory-colored handle. Guede said he tried to staunch Kercher’s wounds, but it was too late. The second murderer story is plausible; investigators found unidentified DNA at the crime scene.

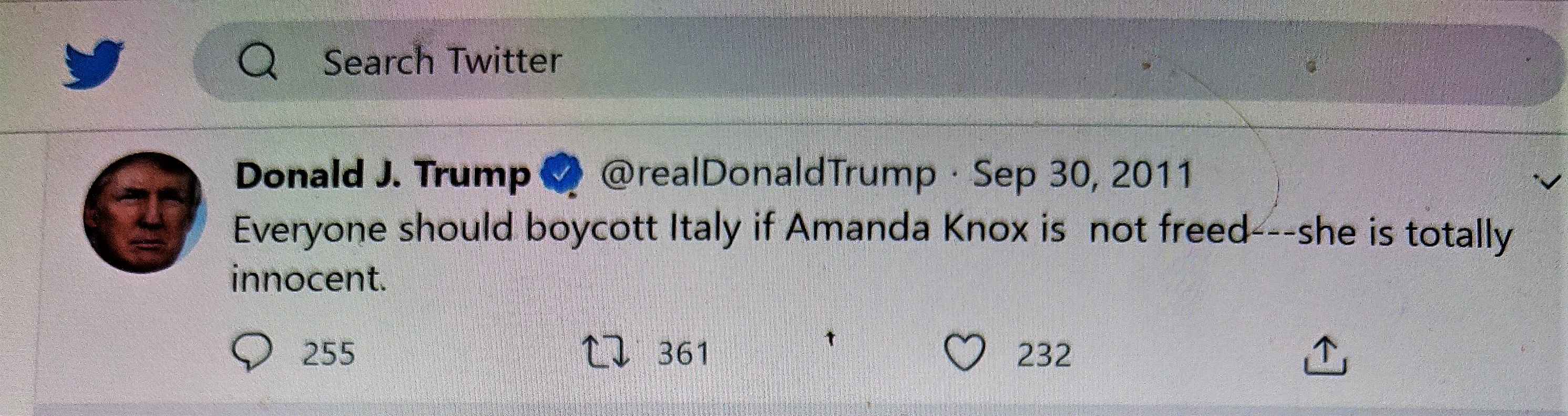

Revelations in the appeal process turned American public opinion strongly in favor of Amanda's acquittal. Donald Trump even weighed in on her behalf, urging that Americans boycott Italy if Knox was not freed.

Five hundred journalists from around the world were on hand for the announcement of the verdict on appeal on October 3, 2011. When Judge Hellman announced the verdict, acquitting both Amanda and Raffaele of all charges (except the slander charge involving Amanda’s naming of Lumumba as the killer), some spectators cheered, others booed. The slander sentence carried a prison term less than what Amanda had already served. She could go home.

Amanda, immediately after learning she would be freed

The following day, Amanda flew home to Seattle with her family. Upon her arrival, she told a supportive crowd at the Seattle airport, “I’m really overwhelmed right now. I was looking down from the airplane and it seemed like everything wasn’t real. What’s important for me to say is thank you to everyone who has believed in me, who has defended me, who’s supported my family.”

Epilogue

Amanda was safe in Seattle, but legal battles continued in Italy for another four years. In 2013, Italy's highest court, the Supreme Court of Cassation, set aside the acquittals on appeal and ordered a new trial. Knox was represented, but remained in the United States. Knox and Sollecito were found guilty.

A final appeal was heard by the Supreme Court of Cassation in 2015. This time the court definitively acquitted Amanda and Raffaele of the murder. In its decision, the Court cited "glaring errors,” “sensational failures,” "investigative amnesia,” and "guilty omissions."

Guede was released from prison. He published a book about the case and his conviction.

On June 5, 2024 the Florence Appeal Court re-affirmed Knox’s conviction for slander involving her statement incriminating Patrick Lumumba. On January 23, 2025 the Supreme Court of Italy confirmed that conviction.

In the years following her acquittal, Amanda married author Christopher Robinson. Amanda worked as a journalist, appeared at events sponsored by the Innocence Project, and dedicated herself to creating awareness of the problem of wrongful convictions. She presently hosts a podcast, “The Truth About True Crime.”