Animal Rights on Trial (2013-2022)

by Douglas O. Linder (2022)

New York Times (by Alex Prager)

Animal Rights on Trial (2013-2020)

by Douglas O. Linder (2020)

In December 2013, a legal document was filed in a county courthouse in the Adirondack town of Johnstown, New York that was unlike any that had ever before been filed in any courthouse in the world. The document was a petition filed by the Nonhuman Rights Project on behalf of Tommy, a chimpanzee living out his old age ten miles away in what the document described as “a small, dank, cement cage in a cavernous dark shed.” The petition asked the court to issue a writ of habeas corpus for Tommy, who the Nonhuman Rights Project asserted was a “person” under New York law, and grant him “immediate release” from his “illegal detention.”

Seven weeks earlier, the Director of the Nonhuman Rights Project, Steven Wise, had seen Tommy in his cage on a lot cluttered with transport trailers, cars, snowmobiles and boats near Gloversville, New York. He knew he’d found the right place when he saw reindeer antlers. The owner of Circle L Trailer, and of Tommy, also had a side business called Santa’s Hitching Post, a reindeer rental business for Christmas events and television ads.

Wise found Tommy crouched in his steel mesh cage watching a nature show on a portable television. He had no chimp companions, a sad situation for a member of a very social species.

Tommy in his cage (photo: NhRP)

Tommy was born in the early 1980s. He was raised from infancy by Dave Sabo, who used to own a business called “Sabo’s Chimps.” Sabo once signed Tommy on for a role as an ape called “Goliath” in the 1987 film, Project X. Bob Barker, the former TV game show host and animal rights activist, claimed that the trainers in the film used clubs to train him.

Tommy became the property of Patrick Lavery in 2008, after Dave Sabo died. Lavery said Tommy was well-cared for. “He likes being by himself,” he would tell a reporter, pointing out that Tommy had a color television to watch. Wise saw things differently. To him, Tommy was “one sad-looking chimpanzee.” He noted living alone year after year could not be an easy thing.

Background

Wise and the Nonhuman Rights Project had decided to focus on winning legal personhood for apes, cetaceans, and elephants. Wise noted that all of these animals are cognitively complex, have their own cultures, are autonomous and self-determining, and have both a theory of mind and a sense of time. It helped, he said, that apes, cetaceans, and elephants also have been researched a lot. There were scientists who could produce detailed affidavits supporting these animals’ impressive cognitive abilities.

These species, from a legal strategy standpoint, had two other things going for them. First, apes, cetaceans, and elephants are not native to North America. And second, they have no large economic value. Granting apes and elephants or dolphins their liberty would not come at a heavy cost to Americans. There are no big American industries lining up to fight against extending them freedom. Imagine, for example, trying to secure freedom for cattle. Think of all those livestock owners, dairy farmers, and food producers you’d have to fight. Freedom for dogs and cats? Well, that poses another set of challenges—think of breeders, pet stores, police dogs…not to mention pet owners.

Steven Wise in his Coral Springs, Florida office

The Nonhuman Rights Project took its fight for animal liberation into the courts knowing that judges were, by and large, a conservative bunch. As Wise put it, “They never want to get too far ahead of society.” The Project decided that a good species to start with would be chimpanzees, who share over 98% of their DNA with humans. And, after a review of habeas corpus law in various states, the Project settled on starting their legal fight, one that Wise acknowledged could take decades, in New York State, where judges might be more open to their common law argument than in many other states. Dozens of chimps were being kept as pets or for entertainment in the United States, and several of those were in New York—including Tommy.

Tommy became the first chimpanzee to have a suit filed on his behalf. The first animal of any kind, actually. The case of The Nonhuman Rights Project on Behalf of Tommy v. Patrick Lavery, filed in Fulton County Court, asked the court to grant a writ of habeas corpus that would have the effect of freeing Tommy from his cement cage. Unlike what would be the usual case for a human being in a habeas action, the Nonhuman Rights Project was not asking simply that the court order Tommy freed. Opening the door of Tommy’s cage to let him wander where he might was no one’s idea of a good plan. Nor did the Rights Project seek to return Tommy to Africa. Captive chimps released into the wild die.

No, Steven Wise had a destination in mind for the chimp: South Florida. Where we all would like to go after we retire, right? Florida was chosen because it was home to perhaps the best sanctuary for chimpanzees in the United States. About two dozen chimpanzees live together on each of thirteen three-to-five-acre islands situated in a large artificial lake in the warm sun. A place with playgrounds, trees, water, and plenty of acreage to romp around or laze about. A place where these autonomous beings could choose who they wanted to be with and what they wanted to do.

Chimps in sanctuary

It was called Save the Chimps sanctuary, located in Fort Pierce. When Wise first toured the sanctuary, he said he could imagine the chimps he’d help free “running around here.” The Sanctuary’s first chimps included the surviving heroes of the NASA space program and others who had been the subjects of years of painful experimentation.

Although the petition filed on behalf of the chimp Tommy was unique in legal history, there had, of course, been many suits brought to protect animals from abusive owners and inhumane treatment, suits that could be called “animal welfare cases.” Animal welfare suits allege that some human owner or institution failed to meet its statutory duty to treat animals well. Animal welfare laws on the books are numerous and diverse. They include, for example, bans on cockfighting, restrictions on puppy mills, prohibitions on the use of exotic animals in circuses, and requirements that ranchers give chickens enough room in their cages to at least lie down. But this was different. Steven Wise called it “a civil rights case”—not an animal welfare case.

New York law states a petition for habeas corpus can be filed by any “person illegally imprisoned or otherwise restrained in his liberty.” Habeas corpus means, literally, “You shall have free the body.” Any “person” may seek the writ. And that would be the key legal question. Was “Tommy” a “person” within the meaning of the law? The position of Steven Wise and the Nonhuman Rights Project was that Tommy was not property, was not “a thing,” but as he is an autonomous being he should have rights of his own, be “a person.”

Personhood

The due process clause of the 14th Amendment says, “No state shall … deprive any person of life, liberty, or property without due process of law.” Any person. The Fifth Amendment imposes the same restriction on the federal government. Persons are entitled to life and liberty.

But what it means to be a “person” is more complicated than one might suppose. In the Citizens United case, for example, the Supreme Court found corporations to be “persons” with First Amendment protections. In fact, the Court has found that numerous things, things without hearts or brains or breath, might be “persons” with rights under the Constitution. Churches, ships, labor unions—the list is long. Personhood is a legal concept, not a biological one.

As for applying this legal concept, the courts have had to grapple with some very contentious moral issues. In the Nancy Cruzan case, the Court held that even someone in a persistent vegetative state, someone without any awareness of her environment, is still a “person” whose wishes about ending—or not ending—life must be respected.

In the case of Roe v. Wade, by contrast, the Court held that a fetus, even a fetus at eight months, is not a “person” whose life or liberty is protected under the Constitution. One becomes a “person,” the Court said, at birth. And that is true regardless of the mental abilities that a newborn baby might have. Even a baby with the most severe mental limitations, with only the most basic brain functions, is still a “person” whose right to life and liberty is deserving of full respect.

Personhood. An interesting and important constitutional question. We speak of liberty and justice for all. But what’s covered by that word “all”?

So a question. Might at least some non-human species be “persons” for some legal purposes? Beings entitled to have their freedom and autonomy respected? To not be locked in cages, to not be the subjects for painful experiments, to not be paraded in front of circus-goers or spectators at a marine park?

Federal judges generally interpret laws in accordance with the intentions reflected in the laws as they were first written, an interpretive approach not likely to lead to a happy outcome for those championing a novel cause such as animal rights. State courts, on the other hand, generally apply common law in resolving habeas corpus cases. In a state habeas corpus proceeding, a judge is more likely to be receptive to considering new evidence that might inform an evolving understanding of liberty, justice—or personhood.

Animal Rights Go to Court

Pursuing habeas corpus claims in state courts became the strategy adopted by Steven Wise, president and founder of the Nonhuman Rights Project. After graduating from law school, he worked as a personal injury lawyer. But he was inspired to take his legal career in a different direction after reading Peter Singer's 1975 book Animal Liberation.

Peter Singer's book, Animal Liberation

The Nonhuman Rights Project was not the first organization to try to use the courts to liberate animals, just the first to use the strategy of filing habeas corpus petitions to do it. An earlier, unsuccessful attempt to free orcas from being held captive for entertainment purposes by SeaWorld was filed in 2011 by the People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals. The PETA suit alleged that SeaWorld’s actions constituted a violation of the Thirteenth Amendment’s prohibition of slavery—arguing, in effect, the orcas were slaves and SeaWorld their master. A federal Judge of the District Court for southern California was not impressed. Judge Jeffrey Miller wrote, “the only reasonable interpretation of the 13th Amendment’s plain language is that it applies to persons, and not to nonpersons such as orcas.” Wise was not happy with PETA’s suit, viewing it as a certain loser that established bad law. “That’s precisely why we’re avoiding the federal courts,” he said.

Orcas performing at SeaWorld

The Nonhuman Rights Projects suit depended on convincing state judges that chimpanzees were persons, at least for purposes of their habeas corpus actions. Wise compared chimps to pre-school-age children. Chimps and young children both exhibit a range of emotions, can understand other minds, and have problem solving abilities. Given a chance, they can master an impressive vocabulary in sign language. Researchers have even seen chimps teaching other chimps sign language—and then watched as those chimps use sign language to communicate among themselves.

And just as three-year olds held in unlawful custody would not be in a position to sue for themselves, chimps need humans to bring an action to enforce their legal rights. At least that was the position of the Nonhuman Rights Project.

The legal filing on behalf of Tommy included affidavits from scientific experts around the world, from Japan to Sweden to the United States. They were unanimous in their belief that chimpanzees shared with humans all the essential abilities and feelings, including autonomy, to make them deserving of rights of their own.

In the day or two before arguments in Tommy’s case, Steven Wise made rounds on national television. He explained in an interview on Good Morning America that a habeas corpus action is appropriate when a person is unjustly held. If Tommy were a human held in a concrete cage without his consent, the case would be a no-brainer. The challenge was getting judges to extend the definition of “persons” to include chimpanzees.

Actually, a dramatic extension of personhood had actually been proposed four decades earlier, by a Supreme Court justice no less. It happened in the 1972 case of Sierra Club v. Morton, a case involving the question of whether the Sierra Club had “standing” to sue for protection of a scenic natural area in California targeted by Disney for a ski resort. The justice who made the proposal, in dissent, was William O. Douglas.

Douglas noted, first off, that inanimate objects like ships and corporations are sometimes considered “persons” for purposes in litigation. Douglas wrote, “So it should be as respects valleys, alpine meadows, rivers, lakes, estuaries, beaches, ridges, groves of trees, swampland, or even air.” He argued that people who have a meaningful relationship to a river, for example, should be able to sue on its behalf. He suggested that fishermen, canoeists, and zoologists all should be free to–quote—“speak for the values which the river represents, and which are threatened with destruction.”

Was Justice Douglas spouting nonsense—or was he just a couple of generations ahead of himself? Well, it is worth noting, perhaps, that in 2017 New Zealand recognized a river as a person for legal purposes.

The Whanganui River in New Zealand, recognized as a legal "person"

But that’s New Zealand. In the U.S., comedian Stephen Colbert had an idea for Tommy’s lawyers. Colbert said, “If Tommy wants to have rights as a person, he should form his own corporation.”

Tommy’s journey through the courts began with a hearing in Fulton County court. The hearing lasted only about twenty minutes. The judge was sympathetic, but thought the matter should go to a higher court. The judge said, “Good luck with your venture. I’m sorry I can’t sign the order, but I hope you continue. As an animal lover, I appreciate your work.” Wise expected nothing different. A judge, he said, “doesn’t want to look like an idiot” and as long as the trial judge made a decision on the record, it got him to the Court of Appeals. That’s where, Wise said, “most common law gets made anyway.”

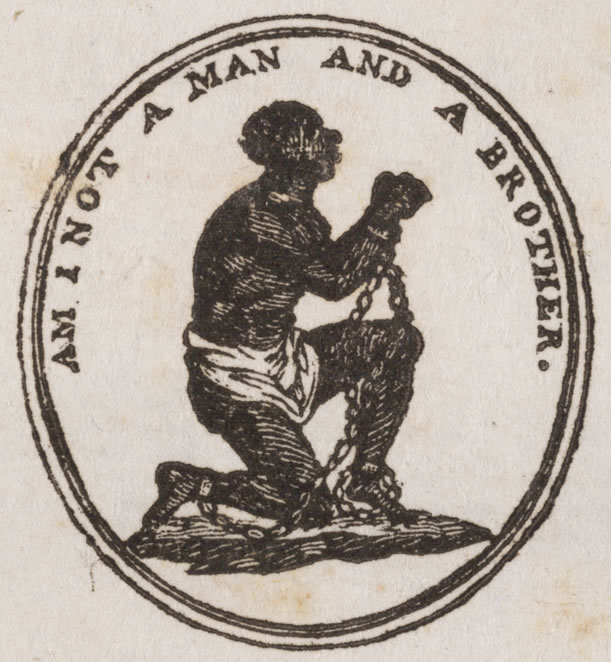

The Nonhuman Rights Project’s appeal was heard by a panel of five judges in a packed courtroom in Albany. Wise got into trouble when he compared Tommy’s legal predicament to that of slaves, who lacked legal rights in England and pre-Civil War America. The argument, while interesting, was fraught with emotion.

But Wise’s comparison was apt. One of the great landmarks of English common law is the 1772 Somerset v Stewart case which was the model for the Nonhuman Rights Project case on behalf of Tommy. In 1772, Judge Mansfield, the chief justice of the English Court of King’s Bench, determined that a slave named James Somerset was a person with legal rights. He granted a writ of habeas corpus. The writ required Charles Stewart, the captain of a slave ship bound for Jamaica, to produce Somerset in court, where he was freed from slavery. Before setting Somerset free, Lord Mansfield said, “Fiat justiciar, ruat coelum” (“Let justice be done though the heavens may fall”). Wise told a writer for the New York Times Magazine, “I’m looking for a Lord Mansfield.”

Judges asked Wise if it wouldn’t be a better approach to lobby the legislature for laws that extend additional protection for chimps held in bad conditions. They asked him whether any court—anywhere—had ever extended “personhood” to a non-human living being. (And, of course, the answer was “no.” But you have to start somewhere.)

The judges pressed Wise about what they saw as an important difference between humans and chimps. We give legal rights to humans, the judges said, but we also impose on them legal responsibilities. That’s the social contract. Could we give legal responsibilities to chimps? What would that even mean? Wise tried to point out that infants and children, the comatose, and those stricken with sever Alzheimer’s, for example, lack the ability to bear legal responsibilities. Yet they are persons with legal rights.

But the judges were unconvinced. In its opinion denying personhood to Tommy, the court wrote, “Unlike human beings, chimpanzees can’t bear any legal duties, submit to societal responsibilities, or be held legally accountable for their actions.” No legal duties, no personhood.

Wise and others at the Nonhuman Rights Project were disappointed, but were determined to press ahead. In late 2015, they filed a new habeas corpus action on behalf of Hercules and Leo, two chimpanzees who were being held by Stony Brook University on Long Island., The filings included 60 more pages of affidavits from experts, including Jane Goodall. Now, for the first time in history, a judge did issue a habeas corpus order that required Stony Brook to come into court and legally justify their right to detain them. The deciding justice, Barbara Jaffe, clearly sympathized with Hercules and Leo and said that in her view, chimps might someday be “persons,” but that she was bound by legal precedent and therefore required to dismiss the case “for now.”

The Nonhuman Rights Project then filed a second suit on behalf of Tommy before Justice Jaffe, who now said that a legal “do over” was not possible in the absence of any new ground.

Steven Wise, for the Nonhuman Rights Project, in court, seeking a writ of habeas corpus.

The Nonhuman Rights Project again appealed. Both for Tommy, and another chimp named Kiko. Kiko was a male chimpanzee held in a cage in a residential area of Niagara Falls. Kiko was in his 30s, and partially deaf—apparently from abuse suffered during the shooting of the made-for-TV movie Tarzan in Manhattan. Kiko bit an actor and was punished by having two trainers hold him while a third struck him on the head with a blunt instrument.

The Nonhuman Rights Project did not contend that Kiko’s new owners were evil people. In fact, Kiko’s owners’ “hearts were in the right place.” The owners “emotionally bonded” with Kiko. They wanted to get Kiko to “a better place,” but lacked the money to do it. Losing Kiko—to them—would be like losing a child. But The Rights Project had photos that showed Kiko with a steel chain and padlock around his neck, which the owners used as a leash.

Tommy and Kiko’s appeal was heard in Manhattan. Wise attacked the reasoning in the previous decision by the court in Albany. He said that if personhood only extended to people with the capacity to bear legal duties, then “millions of humans in New York would also lose the ability to go into court.” Wise was referring to infants, children, incapacitated individuals, and elderly people who cannot fulfill this requirement. He called the earlier decision “unfair, and not backed up by science.”

The appellate court rejected Wise’s arguments. According to the court, the issue had been decided once already, and the second petition was out of line. Wise vowed to seek permission to appeal from New York’s highest court.

But to no avail. The New York Court of Appeals denied the motion seeking permission to appeal. But one judge on the court was not happy about it. Judge Eugene M. Fahey issued an opinion in which he said the court’s failure to take up the issue—quote--“amounts to a refusal to confront a manifest injustice … To treat a chimpanzee as if he or she had no right to liberty protected by habeas corpus is to regard the chimpanzee as entirely lacking independent worth, as a mere resource for human use, a thing the value of which consists exclusively in its usefulness to others.”

Judge Fahey concluded, “The issue whether a nonhuman animal has a fundamental right to liberty protected by the writ of habeas corpus is profound and far-reaching. It speaks to our relationship with all the life around us. Ultimately, we will not be able to ignore it. While it may be arguable that a chimpanzee is not a ‘person,’ there is no doubt that it is not merely a thing.”

The issue isn’t going away. Many people suspect that animal rights will be the big civil rights issue of the rest of the 21st century. Wise sees the battle as a long one, perhaps lasting decades. And, of course, there is no guarantee chimps, elephants, or any other non-human animal will ever gain legal personhood in American courts. Opponents of animal personhood argue that advocates for animal welfare should focus on gaining additional protections for animals through the legislative process, not the courts. They call the animal personhood movement a distraction or worse. They argue that if courts did decide to recognize animal personhood, the courts would then be drawn into endless cases turning on whether animals should be given some other right—and some rights, almost everyone agrees, should be rights for humans only. Rights opponents suggest that equating animals with human beings for personhood purposes would result in some humans, especially those with serious cognitive problem, being treated less well. Richard Posner puts the argument this way: “It is that if we fail to maintain a bright line between animals and human beings, we may end up by treating human beings as badly as we treat animals, rather than treating animals as well as we treat (or aspire to treat) human beings. Equation is a reflexive relation. If chimpanzees equal human infants, human infants equal chimpanzees." Of course, animal rights have their answers to this, and other, objections. Animal rights is an emotional and political issue that is likely to divide courts and defy consensus for the foreseeable future.

But one can even imagine lawyers, someday. arguing that the liberty of chimps is protected under the Bill of Rights and 14th Amendment. No doubt, if you could have asked them, the Constitution’s framers would have told you that they intended to include only human beings within the definition of “persons.” Should that settle the matter? If your answer is “yes,” then perhaps only a constitutional amendment could extend constitutional rights to other species. But you could also be argue that the word “persons” should evolve to reflect our new understanding of animal capacities.

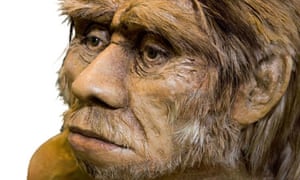

Consider this thought experiment. Next year we discover, to our amazement, living in a remote valley somewhere, a band of Neanderthals. Thought to have gone extinct 37,000 years ago, they reappear. This is a thought experiment, right? So should we treat these Neanderthals, generally considered to be a distinct species, as “persons”? Neanderthals were smart, with brains even larger than the brains of modern humans. They were probably painting caves before Homo sapiens ever thought to do so. They shared over 99% of our DNA. Given a choice between calling a Neanderthal a “person” for legal purposes, or just a thing without rights, which way would you go?

Would we recognize Neanderthals as legal "persons"?

And if you conclude that Neanderthals should qualify as persons, why stop there? We share almost 99% of our DNA with chimps and bonobos. 98% with gorillas. If we don’t draw the line at just our own species, shouldn’t these intelligent species also be called “persons” rather than being lumped with things and denied all legal rights?

And here’s yet another knotty issue we’d need to think through: If Homo sapiens should not stand alone in having legal rights, what are the criteria for deciding which other species should be given rights? Is genetic similarity to humans really the right test? What of elephants, for example? One of the most complex and intelligent mammals on the planet. They bond tightly as family units. They exhibit devotion, compassion, and altruism. They shed tears. They mourn their dead. When elephants come across the remains of an elephant, the herd forms a circle around it and falls silent while they investigate and touch every aspect of the bones with their trunks. Should complex behavior like this serve as a basis for legal personhood?

And we could make the same point about the remarkable capacities of dolphins. So what should be the criteria for legal personhood?

And that brings us to a last point. It’s a familiar problem for lawyers and judges: the “Where-do-you-draw-the-line” problem? If we begin to recognize legal rights for some species, say chimps and elephants, some will ask “Why not dogs and cats?” Why not cows, sheep, and chickens? It’s one thing to free a handful of chimps and elephants and send them off to sanctuaries to live out better days. But the implications of doing so for pets and stock animals are of an entirely different magnitude. Do we take these new claims case-by-case? Or do not start down the path with no obvious stopping point at all?

Happy the elephant at the Bronx Zoo (credit: Gigi Glendinning)

As for that path toward rights for animals, in 2018 Steven Wise was back in New York courts. This time on behalf of an elephant named Happy who resided for decades in the Bronx Zoo. In 1971, Happy was one of a group of seven calves captured, most likely in Thailand, and sent to the United States. Happy resided for five years at a Florida safari park before being shipped to New York. In 2006, Happy was the first elephant to pass the self-recognition test. When scientists painted a white cross over Happy’s eyes and led her to a mirror, Happy repeatedly touched the white cross with her trunk. She knew she was looking at herself. Since 2006, Happy has lived alone at the Bronx Zoo, splitting her time between a one-acre yard and an indoor stall. She is separated by another a fence from another elephant, Patty, but the two elephants can and do touch trunks. Animal rights groups compared Happy's living situation to "a prison," while the Wildlife Conservation Society, which operates the zoo, said Happy "is well cared-for by professionals" with whom she "has strongly bonded."

In September 2019, Justice Alison Tuitt of the Bronx County Supreme Court heard nearly four hours of oral argument in Happy's case. Wise told the court, "New York City is a wonderful place, but Indian Elephants don't belong" there. He noted that Happy only can live on her full 1.1 acres for haflf the year, being kept inside a building for the other half. Wise argued: "This is not how one should treat an elephant, right? It's just not." In February 2020, Judge Tuitt said she was "regrettably" bound by precedent and rejected the habeas corpus petition filed on Happy's behalf. That ruling was affirmed by an appellate court.

In May 2022, Happy's case was heard before the New York Court of Appeals, the state's highest court. Several judges expressed concern that a ruling in Happy's favor would lead to chaos. Judge Rivera asked Monica Miller, Happy's attorney, "Does that mean I couldn't keep a dog?" Miller said no, noting that "we don't have the evidence about dogs we have for elephants right now."

In June, the Court of Appeals, by a 5 to 2 vote, rejected the argument that Happy was being illegally detained in the Bronx Zoo. Chief Judge Janet DiFiore wrote, "While no one disputes the impressive capabilities of elephants, we reject petitioner's arguments that it is entitled to seek the remedy of habeas corpus on Happy's behalf. Habeas corpus, she wrote, "is a procedural vehicle intended to secure the liberty rights of human beings who are unlawfully restrained, not nonhuman animals." In a concurring opinion, Judge DiFiore wrote that a decision in favor of Happy "would have an enormous destabilizing impact on modern society."

Dissenting Judge Rowan Wilson wrote that the court had a duty "to recognize Happy's right to petition for her liberty not just because she is a wild animal who is not meant to be caged and displayed, but because the rights we confer on others define who we are as a society."

The Nonhuman Rights Group said that the two dissenting opinions offer "hope for a future where elephants no longer suffer as Happy has and where nonhuman rights are protected alongside human rights."

Meanwhile, in Argentina in 2016, a chimpanzee became the first ever to be granted a form of legal freedom. An Argentine judge concluded that the chimp Cecilia was a non-human person who had been arbitrarily denied her freedom. Cecilia was ordered removed from the city zoo in Mendoza and taken to a sanctuary in Brazil, where she remains. In 2019, another primate in Argentina, an orangutan named Sandra who had been locked in a concrete enclosure in the Buenos Aires zoo, left for a new life in a U.S. sanctuary, Florida’s Center for Great Apes. (At the sanctuary, Sandra can enjoy the companionship of many other orangutans and chimpanzees, including a chimp named Bubbles, a former companion of the pop star Michael Jackson.) The judge who freed Sandra, Elena Liberatori, told the Associated Press, “With that ruling, I wanted to tell society something new: that animals are sentient being and the first right they have is our obligation to respect them.” Judge Liberatori keeps a large picture of Sandra in her office.

A Final Word

Albert Einstein saw human beings as deeply connected to the natural world. He called our thoughts and feelings that we are “separated from the rest, a kind of optical delusion of consciousness”--a delusion Einstein called “a prison” that restricts our empathy and concern. According to Einstein, quote, “our task must be to free ourselves from this prison by widening our circle of compassion to embrace all living creatures…”

We humans have erected a thick legal wall which leaves just our species on one side and the entire animal kingdom on the other side. Our rights, even trivial interests, are jealously protected. Other species get no protection at all.

Will this legal wall come down? Will the courts chip away at it in the years ahead? Liberty is an evolving concept.