Animal Rights Debate between Peter Singer & Richard Posner

Slate, June 2001

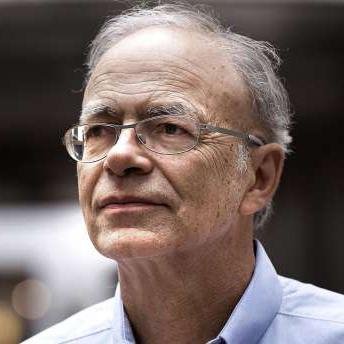

From: Peter Singer

To: Richard A. Posner

Monday, June 11, 2001, at 11:55 PM PT

Dear Judge Posner,

I'm not a lawyer, let alone a judge, but I've noticed increasing interest in legal circles in the topic of the legal status of animals. This seems to have been triggered in part by the efforts of the Great Ape Project, by the publication of Steven Wise's Rattling the Cage, and by the fact several law schools, including Harvard, are now teaching courses on law and animals. You reviewed Rattling the Cage in the Yale Law Journal, and while you were critical of Wise's argument that the law should recognize chimpanzees and other great apes as legal persons, your tone was respectful, and you took his argument seriously. That has encouraged me to attempt to persuade you that—for I am an ethicist, not a lawyer—there is a sound ethical case for changing the status of animals.

Before the rise of the modern animal movement there were societies for the prevention of cruelty to animals, but these organizations largely accepted that the welfare of nonhuman animals deserves protection only when human interests are not at stake. Human beings were seen as quite distinct from, and infinitely superior to, all forms of animal life. If our interests conflict with theirs, it is always their interests which have to give way. In contrast with this approach, the view that I want to defend puts human and nonhuman animals, as such, on the same moral footing. That is the sense in which I argued, in Animal Liberation, that "all animals are equal." But to avoid common misunderstandings, I need to be careful to spell out exactly what I mean by this. Obviously nonhuman animals cannot have equal rights to vote and nor should they be held criminally responsible for what they do. That is not the kind of equality I want to extend to nonhuman animals. The fundamental form of equality is equal consideration of interests, and it is this that we should extend beyond the boundaries of our own species. Essentially this means that if an animal feels pain, the pain matters as much as it does when a human feels pain—if the pains hurt just as much. How bad pain and suffering are does not depend on the species of being that experiences it.

People often say, without much thought, that all human beings are infinitely more valuable than any animals of any other species. This view owes more to our own selfish interests and to ancient religious teachings that reflect these interests than to reason or impartial moral reflection. What ethically significant feature can there be that all human beings but no nonhuman animals possess? We like to distinguish ourselves from animals by saying that only humans are rational, can use language, are self-aware, or are autonomous. But these abilities, significant as they are, do not enable us to draw the requisite line between all humans and nonhuman animals. For there are many humans who are not rational, self-aware, or autonomous, and who have no language—all humans under 3 months of age, for a start. And even if they are excluded, on the grounds that they have the potential to develop these capacities, there are other human beings who do not have this potential. Sadly, some humans are born with brain damage so severe that they will never be able to reason, see themselves as an independent being, existing over time, make their own decisions, or learn any form of language.

If it would be absurd to give animals the right to vote, it would be no less absurd to give that right to infants or to severely retarded human beings. Yet we still give equal consideration to their interests. We don't raise them for food in overcrowded sheds or test household cleaners on them. Nor should we. But we do these things to nonhuman animals who show greater abilities in reasoning than these humans. This is because we have a prejudice in favor of the view that all humans are somehow infinitely more valuable than any animal. Sadly, such prejudices are not unusual. Like racists and sexists, speciesists say that the boundary of their own group is also a boundary that marks off the most valuable beings from all the rest. Never mind what you are like, if you are a member of my group, you are superior to all those who are not members of my group. The speciesist favors a larger group than the racist and so has a large circle of concern; but all these prejudices use an arbitrary and morally irrelevant fact—membership of a race, sex, or species—as if it were morally crucial. h

One closing caution: I have been arguing against the widely accepted idea that we are justified in discounting the interests of an animal merely because it is not a member of the species Homo sapiens. I have not argued against the more limited claim that there is something special about beings with the mental abilities that normal humans possess, once they are past infancy, and that when it is a question of life or death, we are justified in giving greater weight to saving their lives. Of course, some humans do not possess these mental abilities, and arguably some nonhuman animals do—here we return to the chimpanzees and other great apes with which I began. But whatever we decide about the value of a life, this is a separate issue from our decisions about practices that inflict suffering. Unfortunately a great deal of what Americans do to animals, especially in raising them for food in modern industrialized farms, does inflict prolonged suffering on literally billions of animals each year. Since we can live very good lives without doing this, it is wrong for us to inflict this suffering, irrespective of the question of the wrongness of taking the lives of these animals.

Peter Singer

Peter Singer

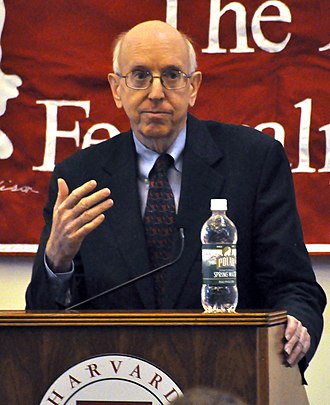

From: Richard A. Posner

To: Peter Singer

Tuesday, June 12, 2001, at 12:00 AM PT

Dear Professor Singer:

I am impressed by your lucid and forceful argument for changing the ethical status of animals; and there is much in it with which I agree. I agree, for example, that human beings are not infinitely superior to or infinitely more valuable than other animals; indeed, I am prepared to drop "infinitely." I agree that we are animals and not ensouled demi-angels. I agree that gratuitous cruelty to and neglect of animals is wrong and that some costs should be incurred to reduce the suffering of animals raised for food or other human purposes or subjected to medical or other testing and experimentation.

But I do not agree that we have a duty to (the other) animals that arises from their being the equal members of a community composed of all those creatures in the universe that can feel pain, and that it is merely "prejudice" in a disreputable sense akin to racial prejudice or sexism that makes us "discriminate" in favor of our own species. You assume the existence of the universe-wide community of pain and demand reasons why the boundary of our concern should be drawn any more narrowly. I start from the bottom up, with the brute fact that we, like other animals, prefer our own—our own family, the "pack" that we happen to run with (being a social animal), and the larger sodalities constructed on the model of the smaller ones, of which the largest for most of us is our nation. Americans have distinctly less feeling for the pains and pleasures of foreigners than of other Americans and even less for most of the nonhuman animals that we share the world with.

Now you may reply that these are just facts about human nature; that they have no normative significance. But they do. Suppose a dog menaced a human infant and the only way to prevent the dog from biting the infant was to inflict severe pain on the dog—more pain, in fact, than the bite would inflict on the infant. You would have to say, let the dog bite (for "if an animal feels pain, the pain matters as much as it does when a human feels pain," provided the pain is as great). But any normal person (and not merely the infant's parents!), including a philosopher when he is not self-consciously engaged in philosophizing, would say that it would be monstrous to spare the dog, even though to do so would minimize the sum of pain in the world.

I do not feel obliged to defend this reaction; it is a moral intuition deeper than any reason that could be given for it and impervious to any reason that you or anyone could give against it. Membership in the human species is not a "morally irrelevant fact," as the race and sex of human beings has come to seem. If the moral irrelevance of humanity is what philosophy teaches, and so we have to choose between philosophy and the intuition that says that membership in the human species is morally relevant, then it is philosophy that will have to go.

Toward the end of your statement you distinguish between pain and death and you acknowledge that the mental abilities of human beings may make their lives more valuable than those of animals. But this argument too is at war with our deepest intuitions. It implies that the life of a chimpanzee is more valuable than the life of a human being who, because he is profoundly retarded (though not comatose), has less mental ability than the chimpanzee. There are undoubtedly such cases. Indeed, there are people in the last stages of Alzheimer's disease who, though conscious, have less mentation than a dog. But killing such a person would be murder, while it is no crime at all to have a veterinarian kill one's pet dog because it has become incontinent with age. The logic of your position would require treating these killings alike. And if, for example, we could agree that although a normal human being's life is more valuable than a normal chimpanzee's life, it is only 100 times more valuable, you would have to concede than if a person had to choose between killing one human being and 101 chimpanzees, he should kill the human being. Against the deep revulsion that such results engender the concept of a transhuman community of sufferers beats its tinsel wings ineffectually.

What is needed to persuade us to alter our treatment of animals is not philosophy, let alone an atheistic philosophy (for one of the premises of your argument is that we have no souls) in a religious nation, but to learn to feel animals' pains as our pains and to learn that (if it is a fact, which I don't know) we can alleviate those pains without substantially reducing our standard of living and that of the rest of the world and without sacrificing medical and other scientific progress. Most of us, especially perhaps those of us who have lived with animals, have sufficient empathy for the suffering of animals to support the laws that forbid cruelty and neglect. We might go further if we knew more about animal feelings and about the existence of low-cost alternatives to pain-inflicting uses of animals. And so to expand and invigorate the laws that protect animals will require not philosophical arguments for reducing human beings to the level of the other animals but facts, facts that will stimulate a greater empathetic response to animal suffering and facts that will alleviate concern about the human costs of further measures to reduce animal suffering.

Richard A. Posner

Judge Richard Posner

From: Peter Singer

To: Richard A. Posner

Tuesday, June 12, 2001, at 11:55 PM PT

Dear Judge Posner,

We agree that humans are animals and that we are not infinitely more valuable than other animals. More importantly, we agree not only on the wrongness of gratuitous cruelty to animals but also that we should incur some costs to reduce the suffering of animals raised for food or other human purposes. I'd hope that this means that we might agree on some practical reforms, for example not allowing veal or pig producers to confine their animals so tightly that they cannot even turn around or walk a few steps. Maybe we would also agree that the United States should follow Europe in phasing out hen cages that prevent the birds stretching their wings or laying in a sheltered nesting area. Since there are alternative forms of production that cost only a few cents per pound or per dozen eggs more, these are modest costs for us, with very large benefits for animals.

Though I'm hopeful, I do not know whether you would support such reforms, because the big question that still divides us is how far we should go to reduce animal suffering. Is there any basis for saying that we can justifiably inflict more suffering on an animal than we would ourselves experience from not inflicting that suffering? In other words, are we justified in giving preference to the suffering of humans, just because it is humans, and not other animals, who are suffering?

You say that you start from the "brute fact that we, like other animals, prefer our own." But who is "our own"? You suggest that it consists of our own family, our "pack," and "the larger sodalities constructed on the model of the smaller ones, of which the largest for most of us is our nation." You point out that Americans have diminished concern for foreigners and less still for nonhuman animals. True, but that is probably something for which President Bush is being taken to task right now, on his European tour, and rightly so. It is not ethically defensible to put the economic interests of Americans ahead of the much greater suffering that continued global warming is likely to bring to millions of people in countries without the resources to defend themselves against climate change.

Of course, sometimes partiality is justified: Children are better cared for by their parents than by strangers, and so we want to encourage family ties. But on the whole, I am more suspicious of common moral intuitions than you seem to be. It is not so long ago that laws persecuting homosexuals were justified by references to the sound moral instincts of ordinary people, and even the Nazis claimed to rest their laws on "the healthy sensibility of the people." Isn't it likely that such reactions rest on instincts that have their roots in our evolutionary history? If so, while we would ignore them at our peril, we do not have to grant them any probative weight. In other words, the fact that people commonly have a given moral reaction does not go much distance toward showing that this reaction is the one they ought to have. Hence I would turn on its head what you say in regard to the clash between intuitive moral reactions and philosophy: Insofar as we are thinking, ethically reflective beings, it is the instinctive reactions, not the philosophy, that have to go. If you do not accept this, then are you also prepared to defend the preference Americans show for those of their own racial or ethnic group? Is it even possible, consistently with the view of ethics that you appear to take, for us to argue on ethical grounds against racism, if we live in a society in which the racist intuitions are deeply entrenched?

I owe you a response to your comments about the wrongness of killing certain categories of human beings, for example those with Alzheimer's disease. People with such conditions have once been capable of expressing their wishes about how they should be treated, if they are ever in such a situation. Where they have done so, we should follow their wishes. If it is more serious to kill a human being with Alzheimer's than to kill a dog with greater mental capacities, this is because of the interests of human beings who do not now have Alzheimer's, but are concerned about how they will be treated if in future they develop such a condition.

In your concluding paragraph you say that what we need to do in order to persuade people to treat animals better is to get them to feel animals' pains as their own. I agree entirely that this is a helpful approach, but it does not make the philosophy irrelevant. When I first began to think about the ethics of our treatment of animals I was living in England in the early 1970s. Empathetic concern for animals was then widespread, but it was commonly dismissed by politicians and the defenders of the status quo as "mere sentimentality." The ethical arguments that I and others developed helped to persuade many people that the treatment of animals was not just something for "animal lovers," but was a serious ethical issue. That change in attitude has put Britain—indeed, the entire European Union—far ahead of the United States in its animal protection law. We do need more empathy, but we also need to take the empathetic feelings we have more seriously. A little philosophy can demonstrate why we should do so.

Peter Singer

From: Richard A. Posner

To: Peter Singer

Wednesday, June 13, 2001, at 12:00 AM PT

Dear Professor Singer:

To begin with an area in which we agree, if it is true that alternative methods of producing meat would substantially reduce animal suffering at trivial cost, I am for adopting them, because I like animals and therefore don't want to see them suffer gratuitously. But I would not be inclined to force my view on others who disagree. I don't see either the necessity or the justification for coercion. If enough people come to feel the sufferings of these animals as their own, public opinion and consumer preference will induce the producers to change their methods. In just the same way, the more altruistic American people become toward foreigners, the greater the costs they'll be willing to incur for the benefit of foreigners.

Where I disagree with you most profoundly is over the question of whether ethical argument either can or should affect how we feel about animals (or foreigners). My view is that ethical argument is and should be powerless against tenacious moral instincts. You point out quite rightly that such instincts often are mistaken. But then the need is for pointing out the mistakes. In the 18th century it was a capital offense in some American states for a human being to have sexual intercourse with an animal. One of the grounds for this harsh punishment was a belief that such intercourse led to the birth of monsters. The belief was unsound, and showing that it was unsound undermined the case for punishment.

To the extent that lack of consideration for animal suffering is rooted in factual errors, pointing out those errors can change our intuitions concerning the consideration that we owe animals. Descartes believed that animals felt no pain—that the outward expressions which we took to reveal pain were deceptive. People who believed this would have no truck with laws forbidding cruelty to animals. We now have good reason to believe that Descartes was mistaken. We likewise have good reason to believe that the Aztecs were mistaken about the efficacy of human sacrifice and that Nazi ideology, like other racist ideologies, rested on misconceptions about evolutionary and racial biology. To accept Cartesian, or Aztec, or Nazi premises and argue merely against the inferences from them would be futile.

To me the most important and worthwhile part of your influential book Animal Liberation is the information it conveys (partly by photographs) about the actual suffering of animals. This information is a valuable corrective to unsound and ignorant thinking. But arguments that do not identify factual errors that underlie or buttress our moral instincts do nothing to undermine those instincts; nor should they. I contended in my reply to your first statement that it is wrong to give as much weight to a dog's pain as to an infant's pain, and that it is wrong to kill one person to save 101 chimpanzees even if a human life is only 100 times as valuable as a chimpanzee's life. I rested these judgments on intuition. Against this intuition you have no factual reply, as you would if my intuition were founded on a belief that dogs feel no pain and that chimpanzees have no mentation.

I said too that the logic of your argument, again at war with our deepest intuitions, was to prefer the life of a dog to the life of a person with Alzheimer's disease. You reply that we should consider the feelings of a person who, knowing that he may someday have the disease, is distressed at the thought of being killed when the disease progresses to a certain point. Fair enough; but what about people, and there are many, who would like to be able to sign an enforceable contract to be killed if they become demented? Such a contract would be unenforceable, and the physician who honored it by killing the Alzheimer's patient would be a murderer. The moral intuition that powers this result may be vulnerable to factual challenge as we learn more about Alzheimer's, as more people suffer from it, and as people come to accept more than they do today the role of physicians as "angels of mercy." What the moral intuition is not vulnerable to is an ethical argument that makes the issue contingent on a comparison of human and canine mental abilities.

I would like, finally, to correct any impression I may have given that I am seeking to justify "giving preference to the suffering of humans, just because it is humans, and not other animals, who are suffering." I don't see myself as engaged, in our debate, in justifying anything except skepticism about the power of philosophical arguments. I do not say that our preferring human beings to other animals is justified—only that it is a fact deeply rooted in our current thinking and feeling, a fact based on beliefs that can change, but not a fact that can be shaken by philosophy. I particularly do not mean to say that we are justified in giving preference to the suffering of humans "just because it is humans" who are suffering. It is because we are humans that we put humans first. If we were cats we would put cats first, regardless of what philosophers might tell us.

Richard A. Posner

From: Peter Singer

To: Richard A. Posner

Wednesday, June 13, 2001, at 8:30 PM PT

Dear Judge Posner,

Your second response leads our discussion into a fundamental question about the nature of ethics. But before I go into that, let me comment on the issue you raise in your first paragraph. Assuming that there are alternative methods of producing meat that would substantially reduce animal suffering at trivial cost, you say that you would like to see these methods spread, but you do not see a justification for coercion. In other words, you do not want to see existing American farming methods prohibited, as many of them already are in Europe. You are prepared to leave this change to consumer choice. That approach would, if carried through consistently, also lead us to reject many other laws, for example those prohibiting the use of child labor or requiring factories to meet basic standards of occupational health and safety.

On this point—in contrast to our initial exchange on the moral status of animals—it seems that my position is more in keeping with common moral views than yours. Of course, I would not argue that this shows that I am right and you are wrong! Rather, I think that there are many cases in which the costs of coercion can be outweighed by the benefits it brings to the weak and the vulnerable. Because many people, regrettably, think only of their own interests, there will always be a market for goods made by unscrupulous producers that are cheaper than those manufactured with greater concern for the welfare of workers, animals, or the environment. It is within the proper scope of democratic government to exclude from the market those who do not meet standards that the majority considers desirable. Or so I would argue.

Let me now bring into this discussion your skepticism about the power of ethical argument, which you say "is and should be powerless against tenacious moral instincts." Even on this view, ethical argument could play a role in settling issues on which there are no tenacious moral instincts. Perhaps the proper scope of democratic government is one such issue. In that case, don't we need ethical argument to resolve the disagreement between us on whether the state should prohibit methods of animal production that cause great suffering for trivial benefits?

But in any case, I don't accept the claim that ethical argument "is and should be powerless against tenacious moral instincts." I wonder why you wrote "and should be" in that sentence. Do you mean that you can offer some reasons against the claim that ethical argument should be allowed to overrule tenacious moral instincts? If so, doesn't that indicate that reasoning, or argument, is the ultimate source of authority in ethics? But if that isn't what those three words mean, what could they mean? That we have a tenacious moral instinct against allowing ethical argument to overrule tenacious moral instincts? I doubt that that is true, and if it were, it would be question-begging to appeal to it.

Perhaps this seems like a mere debating trick that rests on three words that you slipped in without too much thought. But the fact that you did use those words just shows how difficult it is, even for you, to be a thorough-going moral skeptic. Our moral instincts are facts about ourselves and cannot be ignored, but, as I said before, we cannot just take them for granted. (You did not answer my question about how, in a deeply racist society, you think we are able to argue for equal concern for all people, irrespective of race.) We are reasoning beings, capable of seeking broader justifications. There may be some who are ruthless enough to say that they care only for their own interests or for the interests of those of their own group, and if anyone else gets in the way, too bad for them; but many of us seek to justify our conduct in broader, more widely acceptable terms. That is how ethical argument gets going, and why it can examine, criticize, and in the long run, overturn, tenacious moral instincts. Think how far we have come, in a relatively short time, in regard to matters like racial integration, contraception, sex outside marriage, homosexuality, suicide, and many other areas in which moral instincts seemed very strong and very tenacious. It seems very dubious that all these changes have come about simply because we have discovered new facts, and if that is your claim, you owe it to us to tell us what the new facts were, and why they led to changes in moral attitudes.

To return now to the topic with which we began, you have made it clear that you are not seeking to justify the greater consideration we give to human beings over other animals, but merely to say that this preference is "a fact deeply rooted in our current thinking and feeling, a fact based on beliefs that can change but not a fact that can be shaken by philosophy." Since this is itself a factual claim, it is open to empirical disproof. Almost every time I go to a conference discussing issues about animals, someone tells me that Animal Liberation changed their life and led them to become a vegetarian, or an animal activist, or both. You may say that this is because the book gave them some new factual information about how we treat animals. I don't deny that this information contributes importantly to the book's impact, but my impression is that for many people the ethical argument was also crucial. Many of the people who changed their lives as a result of reading the book were not animal lovers, or even particularly interested in animals, or sympathetic to their needs, before reading the book. Almost all of them enjoyed eating meat, and at least one that I recall owned a shop selling leather goods! So their interests were not leading them to become vegetarians, and while I cannot prove that it was the ethical argument that moved them, that is what many of them say, and it does seem the most obvious explanation for the book's success.

Peter Singer

From: Richard A. Posner

To: Peter Singer

Thursday, June 14, 2001, at 12:00 AM PT

Dear Professor Singer:

American children are part of the American community, as a matter both of law and of love. We think it is better for them and for the society as a whole that they should be in school rather than working. We do not consider them income-earning assets of their parents. This has become a deep moral intuition in our society; it is also supported by pragmatic arguments. A more difficult question is whether, by refusing to import goods made with child labor, we should try to coerce foreign countries to adopt our moral norms. Child labor used not to be considered wrong, but that was at a time when few people received an education and when widespread poverty required that all able-bodied persons, of whatever age, be put to work. To the extent that these conditions continue to obtain in Third World nations, it is not obvious that we maximize utility (to use your preferred criterion of social welfare) by seeking to stamp out child labor through boycotts of goods made with it. And I am surprised that you treat as normative what "the majority consider desirable"; for the majority also desire to eat meat.

But all that is an aside. The principal issue you raise is the role of ethical argument. You ask how one can argue against racism in a "deeply racist" society. My answer is, by pointing to whatever fallacious beliefs undergird its racism. If its racism rests not on false beliefs but on material interest, argument will be impotent. There was plenty of argument against Negro slavery before 1861, but it took a Civil War to end the practice.

You ask how it is that our moral norms regarding race, homosexuality, nonmarital sex, contraception, and suicide have changed in recent times if not through ethical argument. This is a large question to which I cannot do justice in the space allotted me. But let me note, first, that philosophers have not been prominent in any of the movements to which you refer. Thurgood Marshall, Earl Warren, and Martin Luther King Jr. had a lot more to do with the development of an antidiscrimination norm than any academic; and the most influential feminists, such as Betty Friedan and Catharine MacKinnon, have not been philosophers either. As far as our changing attitudes toward sex are concerned, the motive forces were again not philosophical or, even, at root, ideological. They were material. As the economy shifted from manufacturing (heavy, dirty work) to services (lighter, cleaner), as contraception became safer and more reliable, as desire for large families diminished (the substitution of quality for quantity of children), and as the decline in infant mortality allowed women to reduce the number of their pregnancies yet still hit their target rate of reproduction, both the demand for women in the labor market and the supply of women in the labor market rose. With women working more and having as a consequence greater economic independence, they demanded and obtained greater sexual independence as well. Nonmarital, nonprocreative sex, including therefore homosexual sex, began to seem less "unnatural" than it had. At the same time, myths about homosexual recruitment were exploded; homosexuality was discovered to be genetic or in any event innate rather than a consequence of a "life style" choice; and so hostility to homosexuals diminished. The history of our changing sexual mores is more complex than this, but this sketch will give a flavor of how I prefer to explain social change. Ethical argument plays no role in the explanation.

You say that some readers of Animal Liberation have been persuaded by the ethical arguments in the book, and not just by the facts and the pictures. But if so, it is probably so only because these readers do not realize the radicalism of the ethical vision that powers your view on animals, an ethical vision that finds greater value in a healthy pig than in a profoundly retarded child, that commands inflicting a lesser pain on a human being to avert a greater pain to a dog, and that, provided only that a chimpanzee has 1 percent of the mental ability of a normal human being, would require the sacrifice of the human being to save 101 chimpanzees. If Animal Liberation had emphasized these implications of your utilitarian philosophy, it would have had many fewer persuaded readers; and likewise if it had sought merely to persuade our rational faculty, and not to stir our empathetic regard for animals.

Richard A. Posner

From: Peter Singer

To: Richard A. Posner

Thursday, June 14, 2001, at 6:00 PM PT

Dear Judge Posner,

This "Dialogue" has been both a pleasure and an enlightening experience. In drawing it to a close, I shall begin by clearing up two misrepresentations of my views in your last message, and then I shall try to pull together some conclusions about the differences between us.

You suggest that I attribute normative significance to "what the majority consider desirable," and that this is inconsistent with my arguments against eating meat. But what I said was: "It is within the proper scope of democratic government to exclude from the market those who do not meet standards that the majority consider desirable." So the normative significance that I give to the views of the majority is only within the context of what a democratic government can properly do. There is no implication that the majority is right. There would be something odd about a democratic government prohibiting the eating of meat if the majority of its citizens were strongly and consistently in favor of meat-eating, but this says nothing about the rights and wrongs of meat-eating itself. Democratic governments often make bad decisions, even though the decisions have been properly made in accordance with the principles of democracy.

You also attribute to me the peculiar position that "provided only that a chimpanzee has 1 percent of the mental ability of a normal human being, would require the sacrifice of the human being to save 101 chimpanzees." There is nothing in my position that requires me to draw that conclusion. Even if the words "1 percent of the mental ability of a normal human being" can be given a clear sense, I have never said that mental ability can be aggregated in this way so as to decide which lives should be saved. k

Now to the main thread of our discussion. My opening argument was that we do wrong when we give animals less consideration, simply because they are not human, than we give to members of my own species. In response you indicated that this is contrary to a deep moral intuition, and then asserted that ethical argument "is and should be powerless against tenacious moral instincts." That sentence made both a factual and a normative claim. I asked you why you made the normative claim, and how you would defend it, but in response you focused on the factual claim. Let me emphasize, therefore, that these are two quite different claims.

On the factual claim, much depends how this is formulated. That ethical argument often struggles in vain against tenacious moral instincts is clearly true—indeed it contains an element of tautology, since if the instincts yielded easily, they would not be tenacious. Yet my own experience, amounting now to more than 30 years of developing ethical arguments on controversial issues, convinces me that ethical argument is sometimes effective even against deep-seated moral views. I do not, by the way, limit the idea of "ethical argument" to "arguments made by academic ethicists." So pointing out that Martin Luther King Jr. and Betty Friedan were not academic ethicists does not show that they did not use ethical arguments or that their arguments were not effective.

If it were evident that no ethical arguments ever moved anyone to change their deep-seated moral intuitions, then there would be little point in discussing the normative claim, that is, whether we should be moved by ethical arguments to reject these intuitions. But since this is not evident, or at least not to me, the normative claim becomes important, and I still want to know why you think that ethical argument should be powerless against tenacious moral instincts. What ethical view can lie behind that claim? Are you prepared to give reasons for it? If so, you are engaging in ethical argument yourself.

Perhaps, however, you will refuse to defend the claim that it would be wrong for ethical argument to be effective against tenacious moral instincts. That would be consistent with some of the things you say, in which you sound like a tough-minded moral skeptic, a kind of modern-day Thrasymachus, who dismisses all of ethics as simply a fraud, covering up more selfish interests. Complete moral skepticism is, certainly, one way of meeting the ethical arguments I have made on behalf of animals, but it achieves that objective at a very high cost, because it means that you cannot make any other ethical arguments either, for example, against racism or homophobia in a society with deep-seated racist or homophobic moral intuitions that do not rest on any factual errors. Note that if you are really a skeptic about ethics, you must conclude not just that these arguments will be ineffective but also that there are no grounds for saying that the racists and homophobes are wrong. If you have to go to these lengths to resist my arguments for a new ethical status for animals, then at least as far as this exchange is concerned, I'm prepared to rest my case and hope that few readers will go along with your far-reaching skepticism about ethics.

Peter Singer

From: Richard A. Posner

To: Peter Singer

Friday, June 15, 2001, at 12:00 AM PT

Dear Professor Singer:

I am not a moral skeptic in the sense of believing that moral beliefs have no effect on human behavior. I am merely skeptical that such beliefs can be changed by philosophical arguments (especially those of academic philosophers, given the sheltered character of the modern academic career in the United States and other wealthy liberal countries), as distinct from being changed by experience, by changes in material circumstances, by the demonstrated success or failure of particular moral principles as means of coping with the problems of life, and by personal example, charismatic authority, and appeals to emotion. In yesterday's exchange I gave examples of how moral principles, for example regarding sex, are changed by such things, and I questioned whether academic philosophy had played any significant role in the changes I discussed.

Although you are correct that the efficacy and the soundness of moral arguments are analytically distinct issues, they are related. One reason moral arguments are ineffective in changing behavior is their lack of cogency—their radical inconclusiveness—in a morally diverse society such as ours, where people can and do argue from incompatible premises. But there is something deeper. Moral argument often appears plausible when it is not well reasoned or logically complete, but it is almost always implausible when it is logical. An illogical utilitarian (a "soft" utilitarian, we might call him or her) is content to say that pain is bad, that animals experience pain, so that, other things being equal, we should try to alleviate animal suffering if we can do so at a modest cost. You, a powerfully logical utilitarian, a "hard" utilitarian, are not content with such pablum. You want to pursue to its logical extreme the proposition that pain is a bad by whomever experienced. And so you don't flinch from the logical implication of your philosophy that if a stuck pig experiences more pain than a stuck human, the pig has the superior claim to our solicitude; or that a chimpanzee is entitled to more consideration than a profoundly retarded human being.

You challenge my example of the 101 chimpanzees. Invoking the positive side of utility (pain is the negative side), you argue that "the ability to see oneself as existing over time, with a past and a future, is an important part of what makes killing some beings more seriously wrong than killing others." It's telling that you say "beings" rather than "human beings." There is scientific evidence that nonhuman primates have some "ability to see [themselves] as existing over time, with a past and a future," and I meant by my example to suggest that this ability might be as much as 1 percent of the ability of the average human being. And then it follows from the logic of your position that it is indeed worse to kill 101 of these primates than to kill a single normal human being, let alone a single retarded human being whose ability to see himself as existing over time, with a past and a future, may be little superior to that of the average chimpanzee. This tough-minded, indeed hard-boiled, conclusion is implied by your statement that "we do wrong when we give animals less consideration, simply because they are not human" (my emphasis).

The "soft" utilitarian position on animal rights is a moral intuition of many, probably most, Americans. We realize that animals feel pain, and we think that to inflict pain without a reason is bad. Nothing of practical value is added by dressing up this intuition in the language of philosophy; much is lost when the intuition is made a stage in a logical argument. When kindness toward animals is levered into a duty of weighting the pains of animals and of people equally, bizarre vistas of social engineering are opened up. You say there would be "something odd about a democratic government prohibiting the eating of meat if the majority of its citizens were strongly and consistently in favor of meat-eating," but you don't say it would be wrong to force vegetarianism on the majority (not all democratic legislation is majoritarian). Nor do you indicate any reservations at all about legislation that would force vegetarianism on a minority of the population that was strongly and consistently in favor of meat-eating. If 49 percent of the population very much wanted to eat meat, would you think it right to forbid them to do so, merely because they were a minority in a democratic system? I infer that you would; and it is an example of why I think we would be better off without philosophical arguments for moral and political change.

You suggest that a vow of abstinence from philosophical argument would disempower us to condemn racism and homophobia. Not so. The causes and consequences of bigotry have a long, well-studied history, rich with lessons that do not require philosophical spin to convince. It is the lessons of history, and not the thought of Plato or Aristotle or Kant or Heidegger, that caused most philosophers, along with nonphilosophers, eventually to turn against racism and homophobia. Philosophy follows moral change; it does not cause it, or even lead it.

Thrasymachus in Plato's Republic, with whom you compare me, taught that might makes right; Socrates, in the Republic, while rejecting Thrasymachus' definition of justice, advocated censorship, the destruction of the family, and totalitarian rule by—philosophers. So moral philosophy has its hard side (consider also Aristotle's defense of slavery, and Kant's of capital punishment) and in our debate, Professor Singer, it is you who are the tough guy, and I the softie, the sentimentalist, willing to base animal rights on empathy, unwilling to follow the utilitarian logic to the harsh conclusions sketched above.

But it would be wrong to end on so negative a note. I wish to end by recording my high personal and professional regard for you. I admire the clarity of your thought and your intellectual courage in pursuing the logic of your philosophy all the way—to its unacceptable conclusions.

Richard A. Posner