The Case for Recognizing the Legal Personhood of Certain Animal Species

The Nonhuman Rights Project undertook what the organization expects will be a decades-long fight to win legal personhood for species with higher level cognitive skill—species such as the great apes, elephants, and cetaceans. With such recognition, the Nonhuman Rights Project would be in a position to potentially, through the mechanism of a court granting a petition for common law habeas corpus, win for animals freedom from their captivity and release to a sanctuary. So far, no court in the United States has recognized personhood for animals.

The arguments below are largely taken from various legal documents filed in connection with the Nonhuman Rights Projects’ advocacy on behalf of chimpanzees and elephants in the state courts of New York and Connecticut or from the writings of Peter Singer, often thought of as the founder of the animal liberation movement.

Steven Wise, Founder and President of the Nonhuman Rights Project

1. Legal “person” is not a synonym for “human beings,” but designates an entity with the capacity to possess legal rights.

Legal personhood is a legal concept, not a biological concept. The Nonhuman Rights Project’s brief in Kiko’s (a chimpanzee) case notes that legal personhood “does not necessarily correspond to the natural order” and that it “may be narrower than ‘human being.’” The brief points out, “For the purpose of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, a human fetus is not a legal person” and that “before the Civil War, human slaves were not legal persons.” At the same time, the concept of legal personhood may be broader than ‘human being’ and include “an entity qualitatively different than a human being.” For example, corporations have long been ‘persons’ within the meaning of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. In other nations, natural features or sacred locations have been designated legal persons. In New Zealand, for example, the Whanganui River has been designated as a legal person under an agreement between indigenous people and the Crown.

The brief notes that “this extension, for good and sufficient reasons, of the conception of personality beyond the class of human beings is one of the most noteworthy feats of the legal imagination.”

2. Excluding animals like chimpanzees and elephants from the definition of legal “persons” is arbitrary and discriminatory.

This point is stressed in the amicus brief filed by a group of philosophers (“Philosophers’ Brief”): “There is a diversity of ways in which humans (Homo sapiens) are ‘persons’ and there are no non-arbitrary conceptions of ‘personhood’ that can include all humans and exclude all nonhuman animals. Various attempts in the literature to justify this approach are self-defeating because they demonstrate that the criteria defending the choice of a specific biological group are actually doing the moral work, and these criteria invariably leave out some humans or include some nonhuman animals. This is because our species, like every other, is the product of gradual evolutionary processes that create an array of similarities between species and an array of differences within them.”

The philosophers do not see species as an appropriate basis for determining membership in the category of “legal persons”: “Species are not ‘natural kinds’ with distinct essences; therefore, there is no method for determining an underlying, biologically robust, and universal ‘human nature’ upon which moral and legal rights can be thought to rest. Any attempt to specify the essential features of ‘human nature’ either leaves out a considerable number of humans—often the most vulnerable in our society—or includes members of other species.” The philosophers add: “When understood as a biological classification, it is difficult to see why species, or indeed any other taxonomic category, should bear any moral weight.”

Philosopher Peter Singer, author of Animal Liberation

3. High cognitive capacity is a sound basis for determining what animals should be considered “persons” for at least some purposes under the law.

The brief of the philosophers puts it this way: “Autonomy is typically considered a capacity sufficient (though not necessary) for personhood. Violations of autonomy constitute a serious harm. The affidavits from primatologists support our view that chimpanzees are autonomous beings.”

“If persons are defined as ‘beings who possess certain capacities,’ and humans usually possess those capacities, then being human can be used to predict with a degree of accuracy that a particular individual will also have those capacities, and be a person. But it is an arbitrary decision to include species membership alone as a condition of personhood, and it fails to satisfy a basic requirement of justice: that we treat like cases alike.” (Philosophers’ Brief).

4. Recognizing Personhood for Animals Will Afford Them Protection in Ways That Animal Welfare Laws Will Not.

Peter Singer argues that animal welfare laws always put human interests above those of the animals they might protect. Singer says: “Before the rise of the modern animal movement there were societies for the prevention of cruelty to animals, but these organizations largely accepted that the welfare of nonhuman animals deserves protection only when human interests are not at stake. Human beings were seen as quite distinct from, and infinitely superior to, all forms of animal life. If our interests conflict with theirs, it is always their interests which have to give way.” (Debate with Posner, 6/11/2001)

5. Animal pain should count just as much as human pain—and we should be equally determined to reduce it whenever possible, through the law or other means.

Singer makes this argument: “The fundamental form of equality is equal consideration of interests, and it is this that we should extend beyond the boundaries of our own species. Essentially this means that if an animal feels pain, the pain matters as much as it does when a human feels pain—if the pains hurt just as much. How bad pain and suffering are does not depend on the species of being that experiences it.”

“The only acceptable limit to our moral concern is the point at which there is no awareness of pain or pleasure, and no preferences of any kind. That is why pigs count, but lettuces don't. Pigs can feel pain and pleasure. Lettuces can't.”

Singer’s focus on pain contrasts, to a degree, with the Nonhuman Rights Projects’ focus on cognitive capacities. It may well be that salmon and turkeys, for example, experience pain, but that fact could hardly be a basis for legal personhood.

Harvard Law Professor Laurence Tribe

6. There is no solid ethical basis for treating humans differently under the law than all other species.

Singer points out: “What ethically significant feature can there be that all human beings but no nonhuman animals possess? We like to distinguish ourselves from animals by saying that only humans are rational, can use language, are self-aware, or are autonomous. (Whether these capacities are uniquely human is, to say the very least, debatable.) But these abilities, significant as they are, do not enable us to draw the requisite line between all humans and nonhuman animals. For there are many humans who are not rational, self-aware, or autonomous, and who have no language—all humans under 3 months of age, for a start. And even if they are excluded, on the grounds that they have the potential to develop these capacities, there are other human beings who do not have this potential. Sadly, some humans are born with brain damage so severe that they will never be able to reason, see themselves as an independent being, existing over time, make their own decisions, or learn any form of language.”

“If it would be absurd to give animals the right to vote, it would be no less absurd to give that right to infants or to severely retarded human beings. Yet we still give equal consideration to their interests. We don't raise them for food in overcrowded sheds or test household cleaners on them. Nor should we. But we do these things to nonhuman animals who show greater abilities in reasoning than these humans.” (Singer, Debate with Posner).

7. Courts in the past have entertained petitions for habeas corpus for slaves, even though they were considered mere things of property under the law, so it’s appropriate to do the same for a chimpanzee.

“Throughout history, the writ of habeas corpus has served as a crucial guarantor of liberty by providing a judicial forum to beings the law does not (yet) recognize as having legal rights and responsibilities on a footing equal to others. For example, human slaves famously used the common law writ of habeas corpus in New York to challenge their bondage, even when the law otherwise treated them as mere things. Holding that Kiko [a chimp] and others like him are not welcome in habeas courts is akin to holding that detained slaves, infants, or comatose individuals cannot invoke the writ of habeas corpus to test the legality of their detention, based on an initial and largely unexamined conclusion about what kinds of substantive legal rights and responsibilities those individuals might properly be deemed to bear in various contexts. . . . The danger habeas corpus confronts – forceful but unjustified restraint and detention arguably in violation of applicable law – can exist even where the habeas petitioner lacks other legal rights and responsibilities.” (Laurence Tribe brief, 3-5)

8. The capacity to bear legal duties is not a precondition for being recognized as having legal personhood.

In his brief in the Kiko case, Professor Tribe argues that it is “a non sequitur” to suggest that “the inability of chimpanzees to bear legal duties rendered it ‘inappropriate to confer upon chimpanzees rights.’” Tribe notes that “even during the era when our Constitution employed various euphemisms to express its toleration of the benighted institution of chattel slavery,” those who were lawfully enslaved still had certain rights, such as the right to appeal criminal convictions. (Tribe brief, 6-9)

The philosophers argue that relying on a theory that the inability of chimpanzees to bear legal duties is a justification for denying personhood misunderstands the nature of the social contract. The brief notes that social contract philosophers such as Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, “maintain that all persons have ‘natural rights’ that they possess independently of their willingness or ability to take on social responsibilities. These rights, which we possess in the state of nature, include the right to absolute freedom and liberty. Upon contracting with our fellows, we do not become ‘persons’, but rather ‘citizens’; and we do not suddenly acquire rights, but rather give up our natural rights, sometimes in exchange for civil and legal rights.”

Rather, what matters, the philosophers argue, is that “Kiko and Tommy [two chimps involved in litigation] are embedded in interpersonal webs of dependency, meaning, and care with other human persons, and so are part of human communities. We have brought Kiko and Tommy into our community and embedded them in social relationships, and so they too should be protected when others exercise arbitrary power over those social ties.” (Philosophers’ Brief).

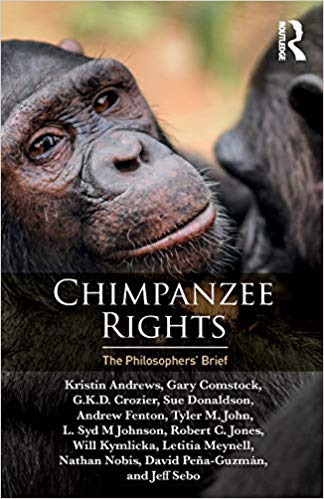

The Philosophers' Brief

9. Who we recognize as legal “persons” express conceptions about the worth of those included or excluded from our definition, and that recognition or non-recognition of personhood in turn shapes social norms and values. Thus, by recognizing personhood for animals, courts can contribute to shaping a society in which those animals are treated more decently than they now are.

This is a subtle, but important point made by Tribe in his brief. Tribe says, “Legal definitions of what and who constitutes a ‘person’ do much ‘more than just regulate behavior’ when it comes to ‘America's most divisive social issues’: they express ‘conceptions of [the] relative worth of the objects included and excluded by personhood,’ and these expressions of ‘law's values’ in turn shape social norms and values.” Tribe adds, “Courts cannot render defensible decisions about the meaning of legal personhood without expressing certain values, whether they want to or not. The question of Kiko's legal personhood implicates a ‘powerfully divisive social issue’ as well as ‘the uncomfortable but inescapable place of status distinctions’ in our legal system.” Tribe argues that on the courts’ answer to the question of legal personhood for chimps hinge "immensely important pragmatic interests." (Tribe brief, 11-12).

10. Courts can recognize chimps as persons for habeas corpus purposes without having to imagine and weigh all the consequences of extending similar protection to other animals.

The brief in the Kiko case makes the point this way: “If a being like Kiko is presumptively entitled to none of the benefits sometimes associated with legal personhood unless and until courts are ready to extend all arguably similar beings every benefit of that legal status, the evolution of common law writs like habeas corpus will remain chained to the prejudices and presumptions of the past and will lose their capacity to nudge societies toward more embracing visions of justice.” At a minimum, the Nonhuman Rights Project argued, courts should accept the responsibility of testing the legality of detention for chimpanzees, even if the ultimate conclusion might be that the detention is lawful: “The court's refusal even to examine the character of Kiko's detention rested on a misunderstanding of the crucial role the common law writ of habeas corpus has played throughout history: providing a forum to test the legality of someone's ongoing restraint or detention. This forum for review has been available even when the ultimate conclusion is that the detention is lawful, given all the circumstances.”