The Matthew Shepard Murder (McKinney and Henderon) Trials (1999): An Account

by Douglas O. Linder (2019)

“Myths aren’t truth, and however complicated the truth is, I think it’s worth finding out. . .If you’re going to base a civil rights movement on one particular incident, you’re asking for trouble, because events are more complicated than most politicians or activists want them to be.” (Journalist Andrew Sullivan, quoted by Stephen Jiminez in The Book of Matt.)

“Matthew Shepard is to gay rights what Emmett Till was to the civil rights movement.” (Sean Maloney, former counsel for the Matthew Shepard Foundation.)

A freshmen at the University of Wyoming fell off his bike while cycling in the Sherman Hills area of Laramie. As he got up, he saw what looked like blood shining off a face about 15 feet away. It was October, so he thought at first it was “a Halloween gag.” But as approached the rail fence, he realized it was not a gag, but a real person, severely injured and unconscious. The cyclist ran to a nearby home.

A deputy from the Albany County Sheriff’s office arrived at the scene minutes later. She saw immediately that a young man had suffered a horrific beating. She could see tracks on his face where tears had washed away the blood. She took the young man, who would later be identified as 21-year-old Matthew Shepard, in her arms. “Little boy, don’t die, please don’t die,” she said. But he would die, just over five days later.

Two suspected killers were quickly apprehended. At a press conference the day after the beating, Sheriff Gary Puls, in response to a question, agreed that Matthew might have been the victim of a hate crime. Matthew Shepard was gay. Tied to the fence as we was, the sheriff allowed that it did look a bit like a crucifixion. With little more than that, a consensus quickly emerged that Matthew Shepard was a martyr; an innocent victim of a hate-driven bashing because of his sexual orientation.

Counsel for the Matthew Shepard Foundation, Sean Maloney, would later say, “Matthew Shepard is to gay rights what Emmett Till was to the civil rights movement.” The killing of Shepard built momentum for passage of a law that would make assaults based on sexual orientation a crime. President Obama signed the Matthew Shepard Act into law in 2009.

But was it really a hate crime? Journalist Andrew Sullivan, himself a gay man, observed, “If you’re going to base a civil rights movement on one particular incident, you’re asking for trouble, because events are more complicated than most politicians or activists want them to be.” The real world is messier than our myths.

So was it a hate crime—or was it something entirely different, a crime that was all about drugs and money? Different participants in the story will give you different answers. To the coroner who conducted the autopsy, it appeared to be a hate crime. To the chief prosecutor, it was mainly a drug-driven crime. To the Shepard family, it was most definitely a hate crime. And what do the two convicted killers have to say? For one, the less culpable of the two, it was a robbery that got out of hand—and had nothing to do with Shepard’s sexual orientation. And for the other killer, the one who inflicted all of the blows, explanations about motive are all over the place. It’s complicated.

Background

Judy Shepard, Matt’s mother, hopes people see her son not as “that saint-like persona that you have given him,” but rather as “just a young man in search of his life.” Although often described by friends who knew him as “sweet,” “charming,” and “bright,” others called him “pompous” or “arrogant.” One thing for sure, Matthew had to deal with a lifetime of troubles in his 21 years. He was the victim of sexual assault as a boy and rape as a young adult. He drank and used drugs heavily. He became HIV positive. And, in large part because of all these things, Matthew had suicidal thoughts and was on anti-depressants the day he was tied, bleeding and dying, to a rail fence on the outskirts of Laramie.

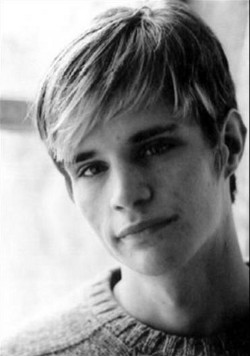

Matthew Shepard was born on December 1, 1976, in Casper Wyoming. He got the nickname “Dandelion Head” as a child from his light-colored hair shooting out in all directions. His father, Dennis, spent a lot of time on the road. He was close, however, to his mother and his younger brother, Logan. School classmates described him as friendly and tender-hearted, but his lack of athletic schools and small size made him the subject of teasing. He received hormone treatments for delayed puberty. Dennis said his son, "liked to compete against himself," entering races he couldn't win and swimming contests he'd finish "dead last by the length of the pool" just to prove he could do it. A boy who sought his father’s approval, but perhaps never felt he got it.

Matthew Shepard

Matthew told friends he was sexually abused as a child—by an adult member of his church, by an older friend, and by a (not close) relative. These life-scarring events probably contributed to Matthew's later bouts with depression (including a suicide attempt at age 15), excessive alcohol consumption, and drug use.

In 1993, Aramco, the oil company for which Dennis Shepard worked, transferred him to Saudi Arabia, and the rest of the Shepard family moved with him. Because the area lacked an American school, Matthew was sent to a boarding school in Lugano, Switzerland for his last two years of high school. He developed a passion for theater, and took German and Italian courses. Matthew said, “Theater provides me with an escape from everyday life.” On a senior class trip to Marrakech, Morocco, Matthew wondered at night from his hotel and was robbed and raped six times by a gang of men in the city’s Old Quarter. Following the attack, he began to experience panic attacks. Matthew, just 5-foot-two and 105 pounds, did not have an easy life. In a Today Show interview, his father called him “The Bad Karma Kid.”

Shepard attended Catawba College in North Carolina in the fall of 1995, where he developed his first close same-sex relationship. He dropped classes the next semester in order to undergo treatment for depression in Raleigh. Later that year, Matthew moved back to Wyoming and attended in classes at the local community college in Casper.

He moved to Denver in the spring of 1997. In Denver, Shepard became addicted to a mix of prescription and street drugs. He began doing crystal meth and made money working as a male escort. Meth was a big part of the club scene, and Shepard began working for a Denver family involved in a drug distribution route running up I-25 from El Paso to Denver through Fort Collins, and then over to Laramie.

Shepard enrolled in 1998 as a 21-year-old freshman political science major at the University of Wyoming in Laramie. By then, Shepard was heavy into drugs. Two friends of Matthew told of a party at his apartment where Shepard, as well as guests, shot up heroin.

Aaron McKinney, the young man who brutally beat Shepard with his .357 magnum revolver, was bisexual. He offered his sexual services to men through an escort service run out a legitimate business called “Doc’s Class Act Limousine Services,” based in Bosler, Wyoming. “Doc’s” actual name was Thomas O’Connor. O’Connor was a former porn star and Hollywood hustler. In the summer prior to Shepard’s murder, McKinney and his wife, Kristen, and their infant child lived for a short time rent-free in a windowless apartment on O’Connor’s property.

McKinney was short (5-foot-four), had the nickname “Dopey,” and had a long record of juvenile crime, including animal abuse. He was known for his violent temper. An acquaintance described McKinney as someone who “always wanted to be seen as bigger, badder, and tougher than anybody.” In 1995, he received $100,000 in a settlement related to the death of his mother following a botched hysterectomy, but quickly drained his bank account on drugs, which he both consumed and dealt.

According to both the former manager and bartender of a gay club in Denver, McKinney would sometimes travel down to the city to hustle guys for what the manager called “twenty dollar jobs.” (McKinney also received money for sex from at least a couple of men in Laramie.) McKinney shared a trailer with a convicted felon. In December 1997, at age 20, he participated in a burglary of a Laramie Kentucky Fried Chicken restaurant, making off with $2500 and a few desserts. He was convicted and awaiting sentencing at the time of Shepard’s murder.

Both McKinney and Shepard used Doc O’Connor’s limos to distribute and use drugs. McKinney’s meth and cocaine, however, came from Laramie suppliers, not Shepard’s Denver-based drug operation. Multiple sources, including a former driver for Doc, according to Stephen Jiminez in his 2013 Book of Matt, said McKinney and Shepard shared round-trip rides from Laramie to Denver in Doc’s limousines. O’Connor told Jiminez of an incident when he was driving his limo with three naked men in back, playing around together. One of them was McKinney. Matthew Shepard, O’Connor admitted, “may have been one of the other guys in back with Aaron.”

Russell Henderson, in contrast with McKinney, seemed an unlikely candidate to be involved in a murder. His landlord described him as “quiet, polite” and “the most American kid you can get.” He collected baseball cards and comic books. He received an Eagle Scout citation from Wyoming’s governor. He pumped gas, enjoyed working on his old Corvair, and played soccer. Henderson got to know McKinney when they began working together as roofers in Laramie. They frequently spent time together as a foursome with their girlfriends.

Jiminez’s sources also reported McKinney and Shepard leaving the Library Bar in Laramie a month or more before the murder to smoke a bowl of meth in a parked car along an alley. The forty-or-so minute encounter ended in an argument, apparently because Shepard refused to sell McKinney (an addict since 1995) any meth without an upfront cash payment. A close friend of Shepard’s, Ted Henson, recalled another incident a few weeks before the murder. Matthew and McKinney ran into each other at a convenience store. McKinney began to yell at Matthew, and when Matt turned to walk back to his car, McKinney yelled, “You better watch your back.”

Friends said in the days leading up to his death, Matthew seemed depressed and was drinking heavily and spending money wildly, even while some friends suspected he had fallen into debt. His depression might be explained by his recent AIDS diagnosis, but rivalries between drug gangs also could have played a part. On October 2, after paying $1100 in cash for a limo ride with his good friend Tina Labrie to the Tornado, a Fort Collins dance club. He told Tina that he didn’t feel safe anymore and lamented that he had gotten “sucked up into the drug scene.” He said he had been having nightmares and brought up the subject of suicide. Matt returned to Laramie in such a dark mood that Tina stayed the night in his apartment. She said that he cried, had a panic attack, and took “around 15” anti-anxiety pills.

In 2004, Elizabeth Vargas asked LaBrie on ABC’s 20/20, “Do you think Matthew owed money for drugs to anybody?” LaBrie replied, “He might have. Or it might have been that he knew too much. I don’t know.”

McKinney, by his own admission, had “been up for about a week” before the murder. A friend of McKinney’s confirmed that fact, describing the meth and cocaine binge as “a hard core bender.” By October 5, McKinney reached the end of his supply. He owed money (according to Jiminez’s sources, about $1200) to someone you’d rather not owe money money to. And he was out of drugs. Neither situation made him happy.

The Murder

On October 6, 1998, Shepard was scheduled to pick up twelve ounces of meth in Denver, drop off six of those ounces in Fort Collins, and then come back to Laramie with the remaining six ounces. For reasons that are not entirely clear, Matthew never made that trip.

Aaron McKinney, meanwhile, was desperate for money or drugs, or both. In the early morning of October 6, he broke into a home hoping to find Monty Durand, a friend who owed him money for drugs. (He had severely beaten Durand three months earlier.) But Durand was not there. He went to work at a roofing job at a nursing home. Joining him at the site was Russell Henderson.

By mid-afternoon, Shepard was at the Library Bar in Laramie. He hung out at the bar until sometime after 6:00, when he left to attend a meeting of the campus LGBTA, where plans were being made for the following week’s events celebrating Gay Awareness Week. A fellow LGBTA member drove Matthew to his apartment on North 12th Street about 9:00.

McKinney and Henderson, after leaving work, drove first to the home of a co-worker, to whom McKinney hoped to sell his .357 magnum for $300, but no deal was made. (McKinney later confessed he actually planned to steal six ounces of meth from a dealer that the co-worker said would be visiting him that evening. Henderson said he wanted nothing to do with the robbery.) After driving around Laramie, and stopping at Henderson’s apartment so he could shower, McKinney and Henderson settled into seats at the Library Bar, where McKinney hoped to hear that his co-worker’s dealer friend had finally showed up. They two men drank a couple of pitchers of beer, then decided to move on.

Shepard drove his Ford Bronco to the Fireside Lounge sometime between 10 and 10:30 PM. Judy Shepard later described the Fireside as “the closest anything came to a gay bar in Laramie, though not ‘gay’ per se.” It was karaoke night. He took a seat at the bar and ordered a beer.

An hour or so later, McKinney and Henderson showed up at the Fireside and took seats at the bar, four or five seats from where Matthew was sitting. They chatted and talked a bit with two women on stools next to them. According to Henderson, it was during this conversation that McKinney brought up robbing Shepard. Henderson said he told his friend, “No, I don’t want to do that.”

Shepard left the bar and approached a table where Mike St. Clair and two friends were nursing drinks. According to St. Clair, Matthew leaned down and made a provocative remark relating to oral sex. St. Clair testified, “It set off something inside me. It made me angry.” St. Clair rejected the invitation.

After 15 or 20 minutes, according to a witness, McKinney got up. He asked the DJ to play a favorite song (the rap song “Getting It”) and danced with a women he knew. Then he moved over to the table where Shepard and St. Clair were sitting and “bummed a cigarette” from Matthew. The two men talked for two minutes or so while Henderson watched television at the bar. Then McKinney and Shepard got up and walked into the bathroom together. What was said inside the bathroom is not known.

Sometime around midnight, McKinney and Shepard walked over to the bar where Henderson was still sitting. McKinney said, “Let’s go.” The three men walked out of the bar and over to the black Ford pickup that Henderson was driving. They head east, through light traffic, out past the Wal-Mart.

McKinney slammed the barrel of his gun into Matthew’s head. Later, McKinney would say later he first struck Shepard after he reached over and grabbed his leg. In a letter from prison to a fellow inmate’s wife, he wrote: “Being a verry drunk homofobick, I flipped out and began to pistol whip the fag with my gun.” But, in his confession, just days after the crime, he told police, Shepard “did not hit on me or make sexual advances.” (Steven Jiminez, in his Book of Matt, suggests that McKinney’s revised story was part of a “calculated attempt on his part to deflect attention” from his own bisexuality. Multiple sources told Jiminez that they observed McKinney and Shepard having sex with each other.)

McKinney told Shepard that he was being robbed. Shepard handed over his wallet; it contained only $30. (It’s possible—maybe likely--that McKinney knew of Shepard’s scheduled drug run that day and expected to find a large amount of cash.) Henderson said he was “shocked” that McKinney continued to beat Shepard after he turned over his wallet. He said he never wanted “Matthew to get hurt out of the whole thing.”

But McKinney did not stop. In an interview on ABC’s 20/20, McKinney said he was “not sure” why he continued to strike Shepard. “I was pushed past my point—my tolerance.” He said his “financial situation” and “drugs I was on” made the violence “a lot worse.” McKinney said that the beating was “like an out-of-body experience,” “surreal,” that he felt like he was “watching the whole thing.” McKinney claimed, “I never meant to kill him.”

McKinney told Henderson to take a dirt road past a subdivision on the edge of town. Still in sight of homes, in a field of sagebrush and prairie grass by a rail fence, they stopped. McKinney pulled Shepard from his car, and Shepard tried to fight back. McKinney asked Henderson to get some rope out of the truck and tie Shepard to the fence, which he did.

The blows kept coming—even as Henderson told his friend to lay off, to just stop it, to leave him alone. McKinney responded by striking Henderson in his face with his gun. (Henderson would receive nine stitches to his face because of his injury.) With Shepard still conscious, Henderson returned to the truck. McKinney—for some reason—asked Shepard if he could read his license plate. And Shepard—for some reason—said that he could. McKinney delivered his final crushing blows and then, as the prosecutor said later in McKinney’s trial, “There is the sound of silence.”

Remarkably, Shepard’s beating would not be the last of the violence for the day for McKinney or Henderson. After leaving Shepard by the fence, the two men drove back into Laramie, with McKinney intent on robbing Shepard’s apartment. But before they get there, they happen to run into two young men puncturing a tire. Henderson confronted them, a fight ensued, and police arrived. Henderson took off through a yard, but was pulled to the ground and cuffed. On the way back to the police car, the arresting officer spotted McKinney’s gun lying on the ground, covered in blood. Henderson was charged with interfering with a police officer and released. But officer Flint Waters told Henderson that if police found someone with a bullet they'd be talking to him again. Henderson, according to Waters, laughed and said, “I guarantee that you won’t find anybody with a bullet in them.”

But they did, seventeen hours later, find Shepard. In the meantime, McKinney and Henderson, together with their girlfriends, had made frantic efforts to hide evidence. Shepard’s wallet was stuffed into a dirty diaper belonging to McKinney’s infant child. Henderson and his girlfriend traveled to Cheyenne to bury bloody clothes. Drugs and drug paraphernalia were dropped in the trash at a fast-food restaurant. Most likely, the sweeping included removing one page from McKinney’s black address book which included the names and phone numbers of friends, organized by first names. The only page missing was the one for listings under the letter “M.”

Shepard was still alive and breathing heavily when he was found. He was brought first to Laramie’s hospital, where the emergency room doctor quickly concluded prospects for survival were virtually non-existent. Matthew was taken by ambulance to Poudre Valley Hospital in Fort Collins.

A license plate inquiry led Detective Rob DeBree to question McKinney about the bloody gun. Before doing so, he looked at the black pickup and noticed “botanical evidence on the hitch” that made him suspect McKinney was involved in the Shepard beating. He read McKinney his Miranda rights.

After the arrests, McKinney penned a letter to Henderson suggesting a common story they should tell investigators. McKinney wrote, “When we got out [to the truck], [Matt] tried to get on me and I started kicking his ass…At no time did we know he was gay until he tried to get on me.”

On the morning of October 8, Henderson, and the two men’s girlfriends were questioned separately at the sheriff’s office. Kristen Price, Aaron’s girlfriend, told police “[Aaron and Russ] just wanted to beat him up bad enough to teach him a lesson, not to come on to straight people.” Not much of Price’s story seemed credible to Detective Ben Fritzen who told her, “It sounds like you guys’ stories are pretty well rehearsed.” Price answered, “Yeah, they are.” Chastity Pasley, Henderson’s girlfriend, also suggested to police the beating had something to do with Shepard’s sexual orientation. She said that Russ had told her that McKinney said to Shepard, “You’re getting jacked; it’s gay awareness week.”

Later that day, Albany County Sheriff, Gary Puls, held a press conference outside the courthouse. Puls indicated that there was evidence that the beating could have been a gay hate crime. In response to a question about Shepard being tied to a fence, he even allowed that it might look to some like a crucifixion. From that moment on, for most people following the Shepard case, the beating turned murder was a hate crime, plain and simple.

Police gather evidence at the crime scene

President Clinton called the Shepard family at the Fort Collins hospital to express his sympathy and pledge the help of the federal government in bringing Matthew’s assailants to justice. He told the press that now was the time for Congress to pass a federal hate crimes bill.

Much of the state’s case against both McKinney and Henderson was based on a confession McKinney gave to police on October 9. McKinney suggested his desire for drugs was the reason that he, Henderson, and Shepard got into his truck. Shepard, he told police, “said he could turn us on to some cocaine or something, some methamphetamines, one of those two, for sex.” (One of Matthew’s closest friends, Ted Henson, said Shepard told him some weeks before the murder that McKinney had offered him sex for drugs, but that Matthew had declined.) Interestingly, when asked about how the events in the Fireside began to unfold, McKinney—in what appears to be a slip-up in his story—told the detective, “We were meeting in the bar.” McKinney said he became angry when Shepard grabbed his leg as the men drove through town.

In a televised interview, McKinney’s girlfriend, Kristen Price, offered another theory, suggesting that the beating occurred because Aaron and Russ “wanted to beat him up bad enough to teach him not to come on to straight people.”

Henderson (r) and McKinney (c) at arraignment (October 1998)

The same day, McKinney, Henderson, Price, and Pasley were arraigned. McKinney and Henderson were put in jail on a $100,000 bond. After Shepard died at 12:53 AM on October 12, first-degree murder was added to the charges against both men. Two days after Matthew’s death, a crowd of 5,000 people assembled on the steps of the U.S. Capitol for a candlelight vigil. On the 16th, a funeral for Shepard took place in Caspar. The Reverend Fred Phelps and other members of the notorious gay-hating Westboro Baptist Church protested nearby, carrying signs like “No Tears for Queers.”

The Trial of Russell Henderson

Although Henderson never struck Shepard, he followed McKinney’s order and tied Matthew to the fence. In addition, he drove the vehicle in which he anticipated a robbery would take place. Under the felony murder theory, Henderson was legally responsible for Shepard’s death. He faced charges of murder, kidnapping, and robbery. He might not have been as morally culpable as McKinney, but he faced long odds against avoiding significant prison time.

There was nothing in the record to suggest Henderson had any animosity toward gays. He said he is in no way “homophobic. I am far from this. I have no hatred toward anyone.”

Wyatt Skaggs, a court-appointed lawyer, defended Henderson. During the jury selection process, Skaggs told potential jurors the case was about the life and potential death of a human being; “the lifestyle of any one individual is irrelevant.” He said “the case is not about hate”—rather the “more mundane motive of a robbery.” He asked jurors to give his client “a fair shot.” Prosecutor Cal Rerucha told jurors that under the Wyoming Constitution, all people—whether straight or gay—are equal.

Prosecutor Cal Rerucha speaks to the press

On April 5, 1999, Henderson’s trial ended before it really began. Skaggs announced that his client would plead guilty to felony murder and kidnapping with the understanding that he would serve (either concurrently or consecutively, that would be up to the judge) two life terms. The plea took the death penalty off the table.

Skaggs might well have had better luck with a jury. The evidence would have shown Henderson’s attempt to stop Shepard’s beating, and Russell being clubbed because of his efforts. A forensic psychiatrist who examined Henderson concluded he was “scared to death” of McKinney. Jurors might have given Henderson a break on the murder charge—perhaps find him guilty only of manslaughter. But fear of the death penalty makes decisions like this difficult for both the defendant and his attorney. No lawyer wants to see his client executed.

A hearing was held on April 5 to consider the plea and determine sentence. Henderson walked to the lectern and turned to Dennis and Judy Shepard. “Mr. and Mrs. Shepard,” he said, “there is not a moment that goes by that don’t see what happened that night. I know what I did was very wrong, and I greatly regret what I did . . . I hope that one day you will have it in your hearts to forgive me.” Turning to Judge Donnell, Henderson said, “I’m ready to pay my debt for what I did. Thank you.”

The judge asked the Shepards if they wished to say anything. Forgiveness was far from their minds. Judy looked at Henderson and said, “I hope you never experience a day or night without feeling the terror, the humiliation, the helplessness or the hopelessness my son felt that night.” Dennis said, “It takes a brave man to help another brave man tie up a person who did not know how to make and clench a fist until he was thirteen years old.”

Then both Henderson’s defense attorney and his prosecutor had their say. Skaggs chose to keep his remarks short, noting in his defense only that Henderson “took responsibility for his actions.” He added, “I will leave it to you to consider his sentence, Your Honor.” Prosecutor Rerucha blasted Henderson, telling him, “You have created hell on earth for a family, for a community, for a state.” Rerucha concluded, “Your Honor, I would ask for consecutive sentences.”

Judge Donnell noted that “many people have called this a hate crime.” The judge said he did not think the case was “so simplistic.” He added that he believed “that a number of motives and emotions were involved here.” Turning to the defendant, Donnell said that regardless of the motive, the facts showed “You drove the vehicle that took [Shepard] to his death. You bound him to that fence…You left him there for sixteen hours.” The judge concluded, “The pain you caused, Mr. Henderson, will never go away. Never.” Henderson, the judge said, would serve his sentences consecutively. A week later, Henderson entered the state penitentiary in Rawlins.

Henderson remains in prison at this writing, with little prospect of being released. An associate warden in a prison where Russell was housed called that “a shame.” Henderson, he said, “doesn’t belong here.”

The Trial of Aaron McKinney

McKinney’s attorneys hit on the idea of what came to be called “the gay panic defense.” They would try to convince a jury that Shepard hit on McKinney, and McKinney flew into an uncontrollable rage—almost a form of temporary insanity. If Aaron’s history of bisexuality were revealed, or if the jury were to learn that McKinney and Shepard previously had sex on multiple occasions, the defense would be a non-starter.

McKinney’s trial opened on October 11, 1999, 364 days after Matthew’s death. The prosecution would have to proceed without the testimony of Henderson, who reversed an earlier decision, probably out of fear.

Fred Phelps protesting as the trial opens

In his opening statement on October 25, prosecutor Cal Rerucha told jurors that the case would not be about the life or lifestyle of Matthew Shepard, rather the crime that occurred one year earlier on the outskirts of Laramie. Rerucha described polite, well dressed and well educated Shepard as someone McKinney saw as “an easy mark.” He said the evidence the state would present against McKinney would be “overwhelming.”

Jason Tangeman, representing McKinney, said his client “did not intend to cause the death of Matthew Shepard.” McKinney beat Shepard during “five minutes of emotional rage and chaos.” It was a crime committed in the “heat of passion.” Not everything Tangeman said in his opening statement was factually accurate. For example, he said that until their encounter in the Fireside, McKinney had “never heard the name Matthew Shepard.”

The defense attempted to show that McKinney’s meth use was the cause of the violent beating. An expert witness testified that the drug can produce both paranoia and hyperactivity, and a potentially dangerous cocktail of emotions.

The defense also tried to show evidence of another factor that they claimed contributed to McKinney’s heat of passion beating of Shepard. Tangeman pointed to two episodes of homosexual abuse suffered by McKinney, the first as a boy of seven and the second as an early teen, part of what the defense lawyer called McKinney’s “confusing, sexually traumatic past.” Tangeman suggested that when Shepard made his alleged sexual advance in front of his friend Henderson, he felt “humiliated” and “his past bubbled up in him.” Tangeman admitted that this so-called (by others, not the defense) “gay panic” response didn’t excuse the beating, but rather justified the jury finding his client guilty only of manslaughter, not murder.

To support the theory that Shepard’s hitting on McKinney threw him into a rage, the defense had a few incidents from Matthew’s past that they could trot out. For example, Shepard had been permanently banned from one Laramie bar for allegedly grabbing a bouncer’s crotch. Any defense strategy that attempts to shift blame to the victim risks infuriating jurors, but they didn’t have much else to work with.

The prosecution case did not include many surprises. Rerucha played for the jury McKinney’s recorded confession, in which he described the murder blow by blow. The prosecution introduced the clothes worn by Matthew on the day of his beating. His bloodied tan shirt and chinos shown pinned to a presentation board. A doctor testified about the level of consciousness Matthew likely experienced during the long hours tied to the fence.

Kristen Price was a star prosecution witness. For her own safety, she was kept hidden at a location outside Wyoming for almost a year before the trial. Price was full of regrets. She regretted hiding evidence. She regretted lying in her original statements to police. And she regretted especially not having notified authorities of the crime at a time when Matthew’s life might have been saved.

Two witnesses for the defense testified about Shepard’s propensity for sexual aggressiveness after drinking. The first was a bartender at a lakeside party Matthew had attended in August 1998. The Cody bartender, who was straight, claimed Shepard made repeated sexual overtures. The bartender told jurors that Matthew “asked me to go behind the van with him. I told him that I was not going anywhere with him and he grabbed my arm so I hit him. I felt bad for hitting him, but he wouldn’t leave me alone.” The second witness was a patron at the Fireside Lounge on the night of the murder. The patron, Mike St. Clair, testified that shortly before McKinney and Russell arrived at the bar, Shepard had approached his table and suggested they have oral sex and “licked his lips” as if he were “trying to be sexy.” St. Clair described Shepard’s actions as “really offensive” and said they made him “angry.”

This line of questioning infuriated the Shepards. In her book, The Meaning of Matthew, Judy said she believed Matthew’s alleged sexual aggressiveness was merely a product of the witness’s “fear-fueled imagination.”

The “gay panic” defense was thwarted, however, when judge Barron Voight that, even if proven, the relationship between McKinney’s early encounters with gay sex would not absolve McKinney on the murder charge. Moreover, such evidence might mislead or confuse the jury. Judge Voight’s ruling on November 1, cutting off the defense’s main argument, meant the case went to jury the next day.

In his closing argument for the state, Cal Rerucha suggested that McKinney and Henderson “pretended to be gay to lure Matthew Shepard out of the bar.” He described the two men as “like two wolves watching a lamb.” He discounted the fact that meth had much to do with crime. He concluded by telling jurors that “Matthew Shepard was not an animal to be hung on a fence. Matthew Shepard was a human being. Matthew Shepard was somebody that loved and cried. Matthew Shepard is a person that deserves your dignity and your protection and your ability to follow the law in this case.”

After ten hours of deliberation, the jury found McKinney guilty of robbery, kidnapping, and second-degree murder. They found him not guilty of premeditated murder. Still, the death penalty remained an option in the second phase of the trial, the penalty phase.

Detective DeBree and the Shepards at a press conference after McKinney trial (November 1999)

There would, however, be no second phase to the McKinney trial. In an unexpected move, McKinney’s lawyers and his prosecutors reached an agreement: prosecutors would drop their pursuit of the death penalty and McKinney would agree to forgo any appeals of his conviction in return for a life sentence without the possibility of parole. The agreement was supported—even pushed—by the Shepards, who did not want to see Matthew’s “reputation dragged through the mud” during the penalty phase of the trial.”

Was Shepard’s Murder a Hate Crime?

The jury never said Matthew’s murder was a hate crime, they just declared it to be a murder. Cal Rerucha said, about whether the Shepard murder was a hate crime, “I don’t think the proof was there.” Police officer Flint Waters, who chased down Henderson just hours after the crime, said “none” of what he learned about the case “appeared to be related” to the “’hate crime’ title.” Elaine Baker, a Laramie woman who had partied with McKinney and Shepard a couple of months before the murder, was even blunter: “Aaron didn’t hate him for being gay. They were friends, for god’s sake.” And McKinney, she noted, was bisexual. But Matthew reminded her of a “frail mouse” and McKinney, she said, was “the cat.”

Motives can be complicated. McKinney was in a foul mood. He struck Russell Henderson with enough force to cause nine stiches and make Henderson fear for his life. He was probably desperate for money and drugs, and he was high on meth.

In an article in Harper’s Magazine in September 1999, Jo Ann Wypijewski suggested that meth dramatically changes how an individual interprets events:

Maybe McKinney is lying and maybe he's not when he says Shepard "mouthed off," prompting him to the fatal frenzy of violence, but one crank-head told me that he once almost wasted someone just for saying hi--"You're so paranoid, you think, `Why is he saying hi?'” And maybe all the meth users I met were lying or wrong or putting me on in saying they immediately took the murder for a meth crime because it was all too stupid and, except for one heinous detail, all too recognizable.

Did Shepard’s sexual orientation have anything to do with the attack? McKinney was bisexual, but closeted. He never was comfortable with his sexuality, either before or after the crime. If, as he claimed, Shepard came on to him in the truck in front of his straight friend, it might have set him off. He might have looked at Matthew, saw a reflection of himself, and not liked what he saw. In one interview, McKinney suggested that Matt's being gay might have been at least a factor in his decision to commit murder. It’s not impossible for a gay person—especially one filled with hate and addled by meth and alcohol--to commit a hate crime against another gay person.

But can that theory be squared with McKinney's own statement in a 2004 interview on ABC's "20/20" that he did not target Shepard because he was gay? In the interview, McKinney told Elizabeth Vargas, " I would say it wasn't a hate crime. All I wanted to do was beat him up and rob him."

Even Jason Marsden, Executive Director of the Matthew Shepard Foundation, concedes that the Shepard murder was not just a hate crime. He said, “I remember thinking at the time that the Matt Shepard case would forever go down in history as, you know, one of the saddest examples of gay bashing, but what it also was, was one of the saddest examples of the desperate lengths people on methamphetamine will go to.”

Regardless of the real story behind Matthew Shepard’s murder, most people will remember it as a hate crime. Matthew was killed just because of who he was: a gay man. Myth trumps fact. Historian Tony Horwitz has noted the staying power of our myths about history. After exploring a number of these inaccurate stories we keep telling ourselves, Horwitz wrote: "I came to the conclusion that no amount of fact is ever going to somehow triumph over these myths. They are with us. People cherish them and need them.”

Epilogue

In 2000, a play by Moisés Kaufman called The Laramie Project premiered. The play drew from interviews with Laramie residents and published new stories about the Shephard murder. The play suggests that hatred of gays was a primary motivating factor for the crime. The play has been used to teach tolerance and promote efforts to combat homophobia.

In 2009, Judy Shepard published The Meaning of Matthew, a book about her son and her family’s efforts to understand and cope with his death, and how to give meaning to Matt’s life by combatting hatred. Judy wrote, “We will continue to do everything we can to keep his story in society’s greater consciousness.”

The Shepard case, as well as The Laramie Project and the work of the Shepard family, provided impetus to the push for a hate crime law. A law that allow federal prosecution of assaults based on the race, sex, religion, national origin, disability, or sexual orientation of the victim. It would be a long time coming, but it happened. In October 2009, President Barrack Obama signed the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act.

Russell Henderson in prison in 2018

Russell Henderson remains in prison, but is not bitter. He said of his confinement, “I belong here for what I did.” McKinney is less remorseful. Stephen Jiminez in The Book of Matt quoted McKinney as saying the “real plan” on the night of October 6 had been simply to rob Shepard. His largest regret is the effect his actions had on the life of Russell Henderson. “I ruined that kid’s life,” he said. “He was a good kid.”