by Douglas O. Linder (2019)

Slavery and what to do about it. It was a question that divided the delegates to the Constitutional Convention in 1787. Some delegates did not want to talk about the morality of slavery. Better to sweep it under the rug. Better to call it a matter of local concern. Better to avoid even using the word "slavery."

Still, the issue had to be faced. Delegate George Mason of Virginia rose to oppose any provision in the new Constitution that allowed the slave trade to continue. Though a slave owner himself, Mason argued that it was “essential” that the Government “have the power to prevent” what he called “this nefarious traffic.” Then he made a point that was both eloquent and prescient. He said:

Every master of slaves is born a petty tyrant. They bring the judgment of heaven on a country. As nations cannot be rewarded or punished in the next world they must be in this. By an inevitable chain of causes and effects, providence punishes national sins by national calamities.

Southern delegates, of course, disagreed. John Rutledge of South Carolina said of slavery: “Religion and humanity have nothing to do with the question.”

Slave auction in New Orleans

In the end, compromises were made in order to secure southern state ratification. One compromise kept federal hands off the slave trade until at least 1808. And another concession to the South was a provision requiring the extradition of fugitive slaves.

And so, as George Mason predicted, there began a chain of causes and effects. Causes and effects that would eventually lead to Civil War.

In this lecture, we will examine two slave trials, one year and half a continent apart. The trials both came as the question of slavery heated up in the 1850s. They raise very different legal issues. But both show that liberty for slaves was just a dream—they couldn’t run and they couldn’t fight back.

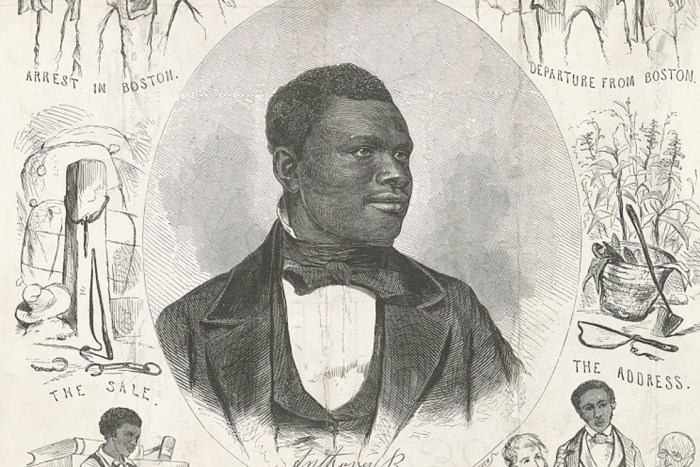

Burns Trial

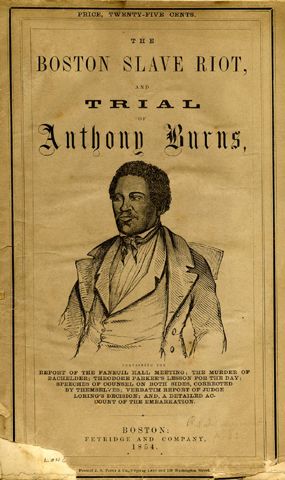

Anthony Burns as enslaved by a series of masters in Virginia beginning at age 7. He mangled his hand in a sawmill accident when he was 12. Against odds and against state law, he learned how to read. Then, as a young man, he became a minister to the slave community.

In late February or early March of 1854, at age 20, with the help of a sympathetic sailor, Burns managed to stow away on a ship bound for Boston. He landed a couple of temporary jobs, then found work in a clothing store.

In a letter to his brother, enslaved in Richmond, Burns revealed that he was living in Boston. The letter fell into the hands of his brother’s master, who in turn conveyed it to Burn’s former master, Charles Suttle.

Suttle wanted his slave back. He went to state court in Virginia to begin the process of recovering Burns. The court declared in a transcript that Suttle had produced “satisfactory proof” of his ownership of Burns. Under the Fugitive Slave Act, such a transcript was deemed “full and conclusive evidence” of escape and that the escaped slave owed service to the party in the record. With his transcript in hand, Suttle set off for Boston to reclaim Anthony Burns.

In Boston, Suttle and William Brent, a Virginian who had purchased Burns’s service for two years, appeared before Commissioner Edward Loring. Faced with the Virginia transcript, Loring felt he had no choice but to issue an arrest warrant for Burns.

Burns arrested

That evening, after leaving work, Burns was grabbed and carried bodily by a half dozen men to the Boston Courthouse. His captors stashed him in the jury room and locked the door. Burns was told he would face a rendition hearing the next morning.

But this was Boston, an abolitionist hotbed. And several members of an abolitionist organization known as the Vigilance Committee showed up in the courtroom the next morning. An antislavery lawyer named Henry Dana offered Burns his services. Burns was reluctant at first, but after a bit of back and forth, he gave his half-hearted support to a defense.

Dana then moved quickly to secure a postponement of the hearing.

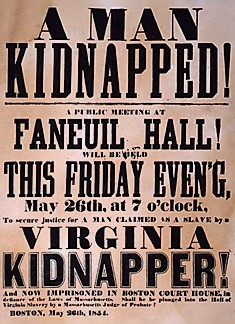

The Vigilance Committee was split between members whho favored non-violent protest in opposition to Burns’s rendition and those who favored an assault on the courthouse to free him. The thirty or so who favored the escape plan met to work out details. Meanwhile, another group of abolitionists met to discuss a plan to pay Burns’s master whatever it took to buy Burns’s freedom.

That evening a crowd of 3 to 5,000 people gathered in Faneuil Hall to protest the rendition proceedings. The abolitionist Wendell Phillips inflamed the crowd by praising the recent murder of a slave owner bent on recapturing a fugitive slave in Pennsylvania. If Burns “leaves the city of Boston, Massachusetts is a conquered state,” Phillips said.

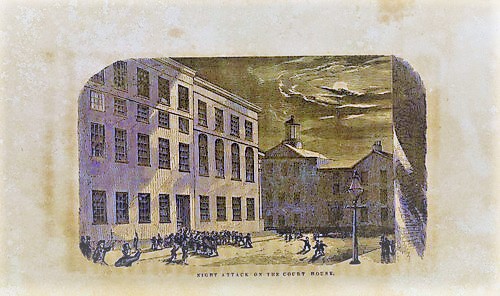

As the protest was about to wind down, someone shouted that a crowd was assembling to rescue Burns. By 9:30, several hundred people had gathered around the courthouse. One man began distributing axes. Several other men used a wooden beam stolen from a nearby construction site and began ramming it against the courthouse’s double doors.

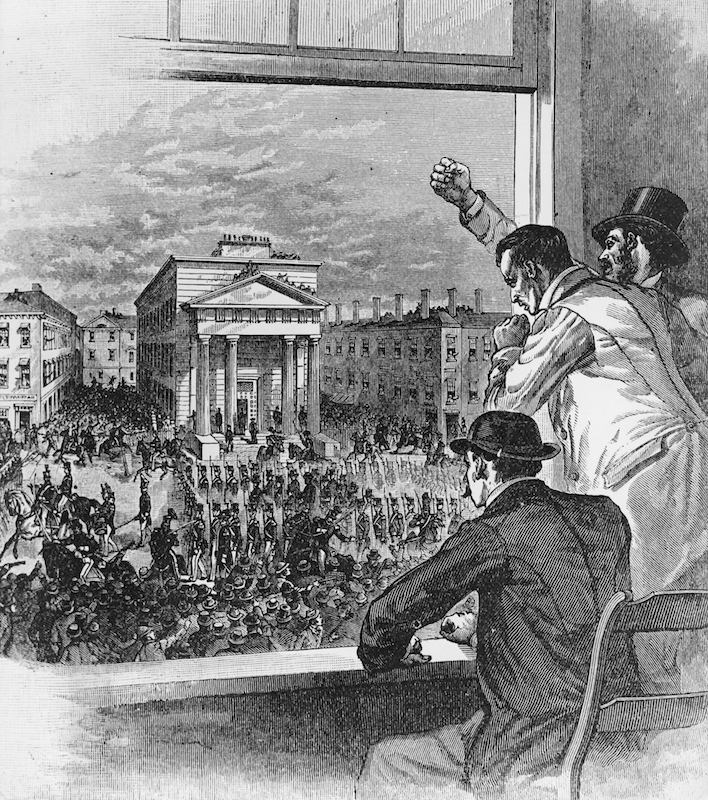

Attack on the courthouse

Inside the doors were the four dozen or so deputies assigned to guard Burns. Eventually, the battering ram broke through. A melee broke out between the deputies and would-be rescuers. One of the guards, a 24-year-old named James Batchelder, collapsed with a wound to his groin and died minutes later.

Before Burns could be rescued, police arrived. They arrested a number of the abolitionists. Boston mayor Jerome Smith called out the state militia to reinforce Burns’s guard. The militia was soon joined by marines after President Franklin Pierce declared, “The law must be executed.”

Two days later, in this highly charged atmosphere, the rendition proceeding resumed. Efforts to buy Burns’s freedom had fallen through, in part because of questions about the applicability of a Massachusetts law that prohibited the sale of slaves.

The rendition hearing turned on both legal and factual questions. The legal questions were whether the fugitive slave certificate issued by Virginia was proper and whether Congress had the power to insist that another state accept that certificate as proof of a slave’s status.

The abolitionists lost on the legal question. So they turned to the factual question. Was Burns actually the man described in the Virginia certificate—or might this be a case of mistaken identity?

William Brent, the Virginian who had hired Burns out, testified to Commissioner Loring that he had known Burns for years and had last seen him in Richmond on March 20. Brent also testified that Suttle talked with Burns at the time of Burn’s arrest. According to Brent, Suttle asked Burns, “Why did you run away?” And Burns replied, “I fell asleep on board the vessel where I worked and, before I woke up, she set sail and carried me off.”

The defense called eight witnesses who reported seeing Burns in Boston between March 1 and March 18. If they really did see him then, Burns couldn’t be the slave Brent saw in Virginia on March 20. Defense attorney Richard Dana also argued that Burns did not match the description of the slave in the Virginia certificate. He pointed out that Burn’s right hand was severely damaged, but the slave in the certificate was described as having only a “scarred” right hand. Also, Burns had a large brand on his left cheek, but the slave in the certificate was only said, again, to have “a scar” on his cheek.

Attorneys for the claimants ridiculed the defense’s effort to show mistaken identity. “It would be difficult to find another colored person in the whole of Boston who so well matches the description as the person at bar.” The claimants also produced a guard who testified that Burns admitted not arriving in Boston until the latter half of March.

In his closing argument for the defense, Richard Dana attacked federal officials for drawing off troops from their “forts and fleets” and assigning them to “this fortified slave pen” so “this great Republic might add to its glories the trophies of one more captured slave.” He argued that the defense had shown reason to doubt that Burns was the slave described in the certificate. Then he warned that if Burns was returned to his master, “He would never see the Virginia sun. He would be sold at the first block, to perish after a few years of service on the cotton fields or sugar fields of Louisiana or Arkansas.”

Dana ended with a plea that Loring hold to “the presumption of freedom ... as to the sheet-anchor of your peace of mind … May your judgment be for liberty and not for slavery, for happiness and not for wretchedness; for hope and not for despair.”

Commissioner Edward Loring

In his ruling, Commissioner Loring made clear he was no fan of the Fugitive Slave Act. He even called the law “cruel and wicked.” The Act, he said, “involves that right, which for us makes life sweet, and the want of which makes life a misfortune.” Still, the law is the law. Burns’s own statements, he said, make clear he is indeed the man described in the Virginia certificate.

Burns, observing Loring, knew what was coming next. He mouthed the word, “No!” Loring concluded, Burns must be returned to the service of his Virginia master.

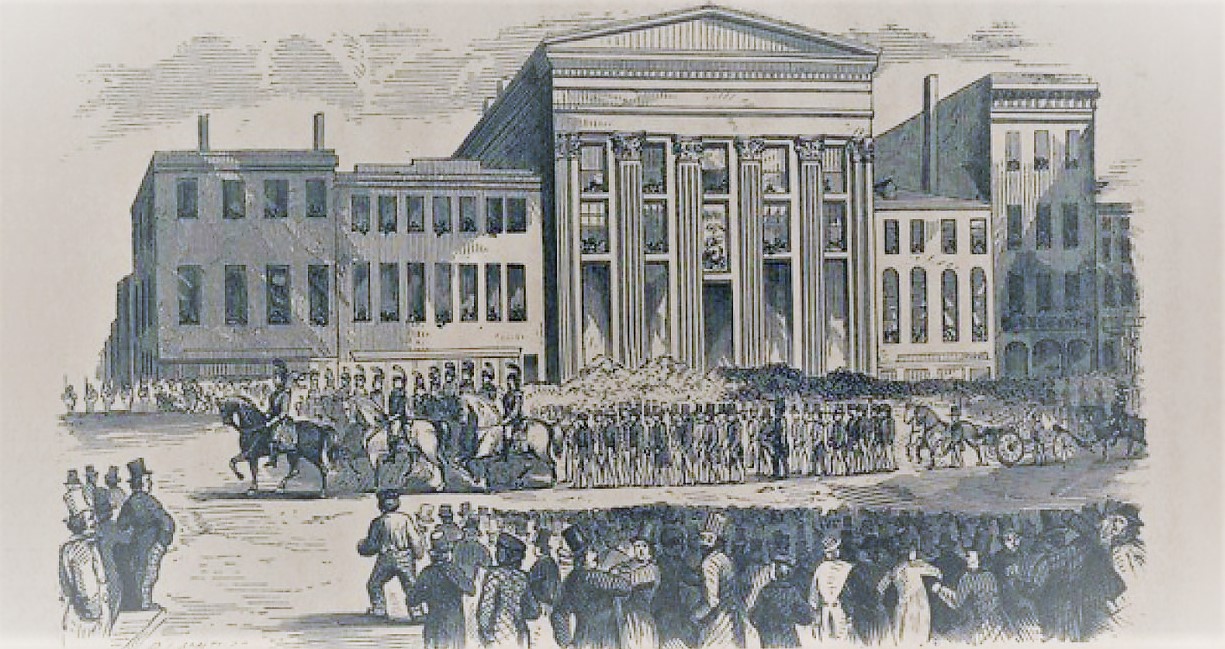

On the day set for Burns to leave Boston, black banners hung from windows. Someone suspended a coffin from a building with the inscription, “The funeral for liberty.” Burns was led from the courthouse by a contingent that included Army infantrymen, marines, and about 100 U.S. marshals. He wore a new frock coat with a silk vest, gifts from his jailers. Boos and hisses echoed from the crowd as the procession made its way to the harbor. Burns was loaded on a steamer, then transported to a larger ship, and taken back to Virginia.

Federal troops in Boston

Burns spent over the next four months in jail, most of it in a cell eight foot square. He was forbidden to have contact with other slaves at the jail, and given only enough food and water to survive. In November, Burns went on auction at a Richmond fair and was sold to a North Carolina plantation owner for $905.

When two clergymen from Boston learned of Burns’s whereabouts, they launched a campaign to buy him and return him to a free state. A deal with Burns’s owner was reached, but it nearly fell through when a crowd surrounded Burns’s owner. One member of the crowd pointed a pistol and demanded that he not sell Burns. They even offered to buy Burns for a higher price themselves. But Burns’s owner insisted that a deal was a deal and he intended to consummate the sale. Eventually, the crowd relented and let him go.

Burns went on to become something of a celebrity. He spoke about his capture and rendition to huge crowds in New York and Boston. P.T. Barnum offered to pay him $100 per week to be a featured attraction in his museum, but Burns declined the offer. He said he didn’t want to “be shown like a monkey.” Eventually, Burns enrolled with a scholarship at Oberlin College and then attended a seminary in Cincinnati. He took a position as the minister for a black Baptist church in St. Catherines, Ontario, Canada.

In Boston, there remained much antipathy toward Edward Loring and his role in the Burns case. The Board of Overseers of Harvard University refused to reappoint Loring to his position on the faculty of the Law School. The Massachusetts legislature voted to remove Loring from another position he held, that of probate judge. A majority report on his removal declared that “Massachusetts required her judges to bring instincts to the bench favorable to liberty and justice and not against them.”

Governor Henry Gardner refused to approve the removal. Gardner said that the removal of a judge for trying to apply a law neutrally, even one the judge might find offensive, was inappropriate. Southern newspapers applauded the governor’s decision. One editorial said: “The governor’s heroic acts … stand out in bold relief ... and beautiful contrast with the black fanaticism which pervades the body politic of his state.”

In 1857, with a new governor in place, the legislature again voted to remove Loring as a state judge. This time the removal address was signed. Democratic politicians in Washington were incensed by the decision to remove Loring. When a vacancy opened on the Federal Court of Claims, President James Buchanan quickly appointed Loring to fill it.

Also in response to the Burns affair, the Massachusetts legislature passed the most radical personal liberty law the nation had ever seen. It prohibited slave claimants from setting foot on state property, required a jury trial whenever the alleged fugitive slave requested one, placed the burden of proof on claimants, and required that claimants prove their cases with at least two credible witnesses who had no personal stake in the case. It also barred Massachusetts lawyers from representing claimants. Burns would be the last fugitive slave to face a rendition hearing in the state of Massachusetts.

The Burns case raised fundamental questions. What should a judge do when faced with an immoral and unjust law—one that denies the most basic of human liberties? Is it his job to enforce the law as written? Or should he find some reason, even if barely plausible, to secure a just result? Or should he just resign, perhaps leaving the decision to a judge with fewer scruples?

Historian and law professor Earl Maltz compared Loring’s dilemma to that faced by Northerners generally in the years leading up to the Civil War: “Whether the integrity of their governing institutions should be maintained even at the expense of providing aid and comfort to the institution of slavery.”

It is a question judges have continued to face. Most notably perhaps, the judges of the Third Reich. Faced with laws compelling sterilization, confinement, and worse—virtually all the German judges chose to enforce those laws, sometimes despite strong personal qualms. In the Justice Trial at Nuremberg, Allied judges decided that was the wrong answer.

TRIAL RECORD (LIBRARY OF CONGRESS PDF)