CHAPTER II.

THE ATTACK ON THE COURT HOUSE

(from Anthony Burns: A History by Charles E. Stevens, 1856)

The news of Burns's arrest quickly spread through the city. It found the public mind in a very different frame from what it had been in at the arrest of Sims, three years before. Those who had been most zealous, on that occasion, for the execution of the fugitive slave act, now stood passive, or openly expressed their indignation at this new attempt. No immediate step was taken, however, except by an association styled a Committee of Vigilance. This association took its origin from the passage of the fugitive slave act. Its sole object was to defeat, in all cases, the execution of that hated statute. Thoroughly organized under a written code of laws, with the necessary officers and working committees arranged on the principle of a subdivision of labor, with wealth and professional talent at its command, actuated by the most determined purpose and operating in secret, it was well fitted to strike powerful blows for the accomplishment of its object. The roll of its members displayed the most diversified assemblage of characters, but this diversity only secured its greater efficiency. The white and the colored race, freeborn sons of Massachusetts and fugitive slaves from the South, here co-operated together. Among them were men of fine culture, and of high social position; men too of renown. Some of the rich men of Boston were enrolled in this committee. A most important portion consisted of members of the Suffolk Bar, by whose counsels the committee were guided through the legal perils of their undertaking. The treasury was bountifully supplied by voluntary contributions. One gave of his poverty what he could, while another subscribed his five hundred dollars. The methods of operation were various. Whatever tended to keep the victim from falling into the grasp of the law, or to rescue him if haply he had already fallen in, was legitimate to their purpose. If a fugitive slave arrived in Boston, he was at once taken in charge. In case there was no pursuit, he remained at ease; but otherwise, he was dispatched at the expense of the Committee on his way to Canada. Sometimes the officers of the law were notified that a certain vessel with a fugitive slave on board would arrive at the port of Boston on a day named; but this Committee of Vigilance had also been notified, and, while the officers were waiting on the wharf for the vessel to come up, the agents of the Committee had taken boat, boarded the ship far out in the harbor, withdrawn the slave,--perhaps under a show of legal authority,--and landed him at some solitary point on shore, where a carriage was in waiting by which he was placed beyond the reach of pursuit. Whenever a slaveholder arrived in the city, he was watched and the object of his visit inquired into. If he had come in the pursuit of ordinary business, he was left alone, but the slightest indication that he was in pursuit of a slave, sufficed to place him under a surveillance that never ceased while he remained in the city. On one occasion, a female slave, while walking in the streets of Boston, suddenly beheld her owner a short distance off, approaching toward her. She turned and fled down another street, notified some of the Committee of the apparition, and the same night was removed from the city. The slaveholder was traced to his hotel, and never lost sight of afterwards. Night and day, his steps were dogged by members of the Committee. When one had followed him a certain length of time, he was passed over to another; now it was a white man, and now a colored man, that, like his shadow, pursued him wherever he went. It was afterward ascertained that he had come to Boston in pursuit of the very slave by whom he had been recognized, but who had fortunately escaped recognition by him.

By this Committee of Vigilance, the case of Burns was now taken in hand. Early in the afternoon of the day following his arrest, a full meeting for the purpose was secretly convened. On the main point there was but one voice; all agreed that, be the Commissioner's decision what it might, Burns should never be taken back to Virginia, if it were in their power to prevent. But there were two opinions as to the method by which they should proceed to effect their purpose. One party counselled an attack on the Court House, and a forcible rescue of the prisoner. The other party were in favor of a less violent course. They proposed to await the Commissioner's decision; then, if it were adverse to the prisoner, they would crowd the streets when he was brought forth, present an impassable living barrier to the progress of the escort, and see to it that, in the melee which would inevitably follow, Burns made good his escape. Both plans were long and vehemently debated, but, without arriving at any decision, the meeting was adjourned till evening. At this second session, the more peaceful method prevailed by a very large majority. For the purpose of arousing the popular feeling to the requisite pitch and also indicating to the public the particular line of action which had been chosen, it was at the same time decided to call a public meeting in Faneuil Hall for the evening following. Another step was, to detail a certain number of men to watch the Court House, night and day, lest the prisoner should be removed unawares. Some, in the excess of their apprehensions, feared that the Commissioner might hold a midnight session of his court, and send Burns back into slavery under cover of darkness. For the convenience of this watch, a wealthy member of the association threw open the loft of his warehouse and liberally furnished it with provisions.

The advocates for an assault on the Court House, though outvoted, were not to be beaten off from their purpose. At the close of the evening meeting, a voice loudly called upon all who were in favor of that mode of action, to tarry after the rest had retired. Fifteen or twenty persons responded to this call; but when it was proposed that they should pledge themselves in writing to engage with force and arms in the perilous enterprise, only seven of the number had the courage to affix their signatures to the agreement. Not dismayed by such severe sifting, these seven still resolved to go forward; and the following night--the night for the meeting in Faneuil Hall--was fixed upon for the execution of their plan.

On Friday morning, the call for that meeting appeared in all the papers and was placarded throughout the city. "To secure justice for a man claimed as a slave by a Virginia kidnapper, and imprisoned in Boston Court House, in defiance of the laws of Massachusetts"--thus began the notice. "Shall he be plunged into the hell of Virginia slavery by a Massachusetts Judge of Probate?"--was the more ominous interrogatory with which it closed. By eight o'clock in the evening, the venerable Hall was filled to overflowing. The assembly was called to order by Samuel E. Sewall, a distinguished citizen of Boston. George R. Russell, an ex-mayor of the neighboring city of Roxbury, was placed in the President's chair, while among the Vice-Presidents were several gentlemen who had been of the Governor's Council, together with Dr. Samuel G. Howe, the distinguished philanthropist and historian of the Greek Revolution. Dr. Henry I. Bowditch and Robert Morris, the colored lawyer of Boston, filled the post of Secretaries.

The subject of the evening was introduced by the President in language of sarcasm and irony. "I once thought," said he, "that a fugitive could never be taken from Boston. I was mistaken! One has been taken from among us, and another lies in peril of his liberty. The boast of the slaveholder is, that he will catch his slaves under the shadow of Bunker Hill. We have made compromises until we find that compromise is concession, and concession is degradation. The question has come at last, whether the North will still consent to do what it is held base to do at the south. When Henry Clay was asked whether it was expected that northern men would catch slaves for the slaveholders, he replied: 'No! of course not! We will never expect you to do what we hold it base to do.' Now, the very men who had acquiesced with Mr. Clay, demand of us that we catch their slaves. It seems that the Constitution has nothing for us to do but to help catch fugitive slaves! When we get Cuba and Mexico as slave states, when the foreign slave trade is re-established with all the appalling horrors of the Middle Passage, and the Atlantic is again filled with the bodies of dead Africans, then we may think it time to awaken to our duty. God grant that we may do so soon! The time will come when slavery will pass away, and our children shall have only its hideous memory to make them wonder at the deeds of their fathers. For one, I hope to die in a land of liberty--in a land which no slave-hunter shall dare pollute with his presence."

Dr. Howe presented a series of resolves that were subsequently adopted by the assembly as the expression of its sentiments. They embodied these epigrammatic sentences: "The time has come to declare and to demonstrate the fact that no slavehunter can carry his prey from the Commonwealth of Massachusetts."--"That which is not just is not law, and that which is not law ought not to be obeyed."--"Resistance to tyrants is obedience to God."--"Nothing so well becomes Faneuil Hall, as the most determined resistance to a bloody and overshadowing despotism."--"It is the will of God that every man should be free; we will as God wills; God's will be done."--"No man's freedom is safe unless all men are free."

One of the ex-councillors of state gave his voice for "fighting." John L. Swift, a young lawyer of fervid oratory, next addressed the assembly. "Burns," said he, "is in the Court House. Is there any law to keep him there? If we allow Marshal Freeman to carry away that man, then the word, 'Cowards,' should be stamped upon our foreheads. When we go from this Cradle of Liberty, let us go to the tomb of liberty, the Court House. Tomorrow, Burns will have remained incarcerated there three days, and I hope to-morrow to witness, in his release, the resurrection of liberty."

There were two men in the Hall for whose words, more than for those of all others, the assembly impatiently waited. These were Wendell Phillips and Theodore Parker. Regarded by the public as the leaders of the present enterprise, closely associated in spirit and purpose, and eminent, both, for the power of speech, they yet differed from each other in many particulars. Mr. Phillips belonged to the aristocracy, so far as such a class may be supposed to exist in this country. He had an ancestry to boast of; his family name was interwoven with the history of the Commonwealth; and some of those who had borne it had filled high offices in the government. Mr. Parker, on the other hand, was of more plebeian origin; he had been the architect of his own fortunes, and was by far the most distinguished person of his lineage. In religion, Mr. Phillips was a Calvinist, and believed that the Holy Scriptures were the inspired word of God; while Mr. Parker, rejecting all creeds and disowned by all sects, held the Bible to contain only the wisdom of fallible men, and claimed for himself and for future sages the possible power of improving thereon. Mr. Phillips was a lawyer, but he seldom appeared in the courts; Mr. Parker was a clergyman, and, though without a church and eschewing the holy sacraments, preached constantly to a large but shifting congregation. Mr. Phillips excelled in oratory, Mr. Parker was a greater master of the pen. The former studied men, the latter, books. Mr. Parker had a wider reputation--Europe had heard of him; but those who knew both would have forsaken him to hang upon the lips of Mr. Phillips. Mr. Parker had secured his triumph when he had uttered his speech; Mr. Phillips found his chief satisfaction in the accomplishment of the end at which his oratory was aimed. Mr. Phillips had the garb and gait of a gentleman; Mr. Parker, as he moved along with stumbling steps and prone looks, had the aspect of a recluse student. In their physical characteristics, they differed not less than in mental and moral traits. Mr. Phillips was a person of commanding height and elegant proportions; his features were cast in the Roman mould, his head was rounded and balanced almost to the ideal standard. A ruddy complexion, fair hair, and eyes of sparkling blue, showed him to be of the true Saxon race. Mr. Parker, on the contrary, was of inferior stature and ungraceful form; he had the face of a Diogenes, and his massive head, capacious of brain in the frontal region, was not symmetrically developed. He had an atrabiliar complexion, dark hair, and large, dark eyes that looked forth from behind spectacles with a steady, unwinking gaze.

The speeches of both, on the present occasion, were so imperfectly reported that the public abroad had but a faint conception of their power and effect. Mr. Phillips was the first to speak. "The city government is on our side," began the orator; a storm of cheers greeted the announcement. "I am glad," continued he, "to hear the applause of that sentiment. If the city police had been warned on the Sims case, as they are now, not to lift a finger in behalf of the kidnappers, under pain of instant dismissal, Thomas Sims would have been here in Boston to-day. To-morrow is to determine whether we are ready to do the duty they have left us to do. There is now no law in Massachusetts, and when law ceases, the people may act in their own sovereignty. I am against squatter sovereignty in Nebraska, and against kidnappers' sovereignty in Boston. See to it, that tomorrow, in the streets of Boston, you ratify the verdict of Faneuil Hall, that Anthony Burns has no master but his God.

"The question is to be settled to-morrow, whether we shall adhere to the case of Shadrach or the case of Sims. Will you adhere to the case of Sims, and see this man carried down State Street, between two hundred men? I have been talking seventeen years about slavery, and it seems to me I have talked to little purpose, for within three years, two slaves can be carried away from Boston. Nebraska, I call knocking a man down, and this is spitting in his face after he is down. When I heard of this case, and that Burns was locked up in that Court House, my heart sank within me.

"See to it, every one of you, as you love the honor of Boston, that you watch this case so closely that you can look into that man's eyes. When he comes up for trial, get a sight at him, and don't lose sight of him. There is nothing like the mute eloquence of a suffering man to urge to duty; be there, and I will trust the result. If Boston streets are to be so often desecrated by the sight of returning fugitives, let us be there, that we may tell our children we saw it done. There is now no use for Faneuil Hall. Faneuil Hall is the purlieus of the Court House to-morrow morning, where the children of Adams and Hancock may prove that they are not bastards. Let us prove that we are worthy of liberty."

Theodore Parker followed his coadjutor. Addressing the assembly as "fellow subjects of Virginia," he poured forth a torrent of the most bitter invective. At the close, he proposed that when the meeting adjourned, it should be to meet in Court Square, the following morning, at nine o'clock. "To-night," shouted a hundred voices in reply. The speaker stood silent, as one in doubt. At length he called on those who were in favor of proceeding that night to the Square, to raise their hands: half the assembly did so. But now the excitement burst through all bounds,--the vast Hall was filled with one wild roar of voices. "To the Court House," was shouted in one quarter; "to the Revere House for the slave-catchers," was answered back from another. In vain Mr. Parker attempted to allay the tumult,--his voice was submerged in the billows of sound, and he stood gesticulating like one in a dumb show. A potent master of the weapons that are fitted to goad the public mind even to madness, he lacked the sovereign power to control and subdue at will large masses of men. Amid the uproar, Wendell Phillips again ascended the platform. The different quality of the two men then appeared. Ere half a dozen sentences had fallen from his lips, the assembly had subsided into profound stillness.

"Let us remember," said he, "where we are and what we are going to do. You have said, to-night, you will vindicate the fair fame of Boston. Let me tell you, you won't do it by groaning at the slave-catchers at the Revere House--by attempting the impossible act of insulting a slave-catcher. If there is a man here who has an arm and a heart ready to sacrifice anything for the freedom of an oppressed man, let him do it to-morrow. If I thought it would be done to-night, I would go first. I don't profess courage, but I do profess this: when there is a possibility of saving a slave from the hands of those who are called officers of the law, I am ready to trample any statute or any man under my feet to do it, and am ready to help any one hundred men to do it. But wait until the daytime. The vaults of the banks in State street sympathize with us. The Whigs, who have been kicked once too often, sympathize with us. It is in your power so to block up every avenue, that the man cannot be carried off. Do not, then, balk the effort of to-morrow by foolish conduct to-night, giving the enemy the alarm. You that are ready to do the real work, be not carried away by indiscretion which may make shipwreck of our hopes. The zeal that won't keep till to-morrow will never free a slave."

By this time the orator had his audience well in hand, when suddenly a man at the entrance of the Hall shouted: "Mr. Chairman, I am just informed that a mob of negroes is in Court Square attempting to rescue Burns. I move that we adjourn to Court Square." A formal vote was not waited for, and the next instant the whole mass was pouring down the broad stairs and along the streets toward the new theatre of action.

It is necessary to return and follow the movements of the little band that had pledged themselves to the forcible rescue of Burns. A place of rendezvous had been appointed, but when the time for meeting arrived, only six of the seven appeared. The defection of their faint-hearted companion did not shake the purpose of the rest. Feeling, however, that their number was too small, they agreed to go forth, and, if possible, secure each man six coadjutors. This effort was so successful that in a short time the number of confederates was increased to nearly twenty-five. Their weapons of attack were various; some were armed with revolvers, some carried axes, and some butcher's cleavers that had just been purchased and were left in their paper coverings for better concealment. In a passage-way hard by, a large stick of timber had been secretly deposited to serve as a battering-ram. Soon after nine o'clock, everything was ready for the assault. It was at this juncture that the alarm had been given to the meeting in Faneuil Hall.

Scarcely had the crowd from the Hall begun to pour into the Square when the assault was commenced. The lamps that lighted the Square had already been extinguished, so that under cover of darkness the assailants might more easily escape detection. Strangely neglecting the eastern entrance, which was not secured at the time, (Col. Suttle happened to be in the Court House at the time, and escaped by the east door after the attack commenced, leaving to Batchelder and others the business of defending his property at the risk and sacrifice of their lives) they passed round to the west side and commenced the attack in that quarter. The Court House on that side presented to the eye an unbroken facade of granite two hundred feet long and four stories high. In the lower part were three entrances, closed by massive two-leaved doors which were secured by heavy locks and bolts. Against the middle one of these doors, the beam which had been previously provided, was now brought to bear with all the force that ten or twelve men could muster. At the same moment, one or two others plied their axes against the panels. As the quick, heavy blows resounded through the Square, the crowd, every moment rapidly increasing, sent up their wild shouts of encouragement, while some hurled missiles against the windows, and others discharged their pistols in the same direction. In two or three minutes, a panel in one part of the door had been beaten through; the other part had been partially forced back on its hinges, when the assailants found their entrance obstructed by defenders within. The Marshal, whose office was in the building, although not anticipating the attack, was not altogether unprepared for it. In the course of the day, he had appointed fifty special aids, and posted them in different parts of the spacious building; he had also caused to be deposited in his office a large quantity of cutlasses. On the first alarm, the specials were hastily armed with these weapons and set to defend the assaulted door. As often as the pressure from without forced it partially open, it was closed again and braced by the persons of those inside. While thus engaged, one of the Marshal's men, a truck-man named Batchelder, suddenly drew back from the door, exclaiming that he was stabbed. He was carried into the Marshal's office and laid upon the floor, where he almost immediately expired. It was discovered that a wound, several inches in length, had been inflicted by some sharp instrument in the lower part of his abdomen, whereby an artery had been severed, causing him to bleed to death. A conflict of opinion afterward arose respecting the source from whence the blow proceeded. Some affirmed that it was an accident caused by one of his own party. It was said that Batchelder was engaged at the moment in bracing one part of the door with his shoulders; that while he was in that half-stooping posture, another of the specials, seeing through the opening the hands of one of the assailants, aimed at them a blow with a watchman's club, which, missing its mark, fell upon the head of Batchelder and drove him down upon the blade of his own cutlass. Another, and perhaps more probable account was, that while Batchelder stood bracing the door behind the broken panel, the wound was inflicted by an arm thrust through from the outside, not with any murderous intent, but to compel him to relax his hold.

In the temporary confusion within, caused by this fatal result, the leader of the assailants, the Rev. Thomas W. Higginson, succeeded in forcing his way into the building. None followed him, and the door was almost instantly closed again. For a moment he was alone, face to face with his adversaries; the next, he re-appeared on the outside, exclaiming to his associates, "You cowards, will you desert us now?" (Two others, of those engaged in the attack, effected an entrance a few moments later, and after Mr. Higginson's repulse.) A sabre cut across the chin, and other marks, attested the rough reception he had encountered while within the walls. The courage and daring displayed by this person showed him to be a fit leader in such an enterprise. He could trace his lineage directly back to one of the most distinguished of those who with Endicott at Salem began the foundations of the Commonwealth. Almost at the same moment with his repulse, eight or nine of his companions were seized by the police, who had quietly mingled in the crowd, and were borne off to the watch-house. Intimidated by this sudden and successful movement, and weakened by the loss of their comrades, the rest made no further attempt, and very soon the crowd began to disperse.

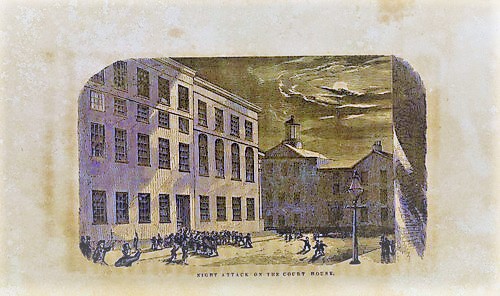

The room in which Burns was confined, was on the side of the building against which the attack was directed, and in one of the upper stories. Burns had received a hint of the intended assault, but his keepers were entirely unprepared for it. The first sounds made by the assailants below, filled them with extreme terror. Abandoning their customary pastime of card-playing, they hastened to extinguish the light, and to close the blinds at the windows. Burns was then placed against the wall between the two windows, for security against any chance shot that might enter the room, while they themselves crouched upon the floor in the farthest corner. A box of pistols and cutlasses had been placed in the room on the same day; this, Burns was forbidden to approach. Their position did not justify such an excess of fear. The extreme height of the room from the ground placed it beyond the reach of danger from the outside, while the door was barricaded by seven massive iron bars extending from top to bottom at intervals of not more than a foot. (The room in which Burns was confined, is indicated in the preceding engraving by the lighted window in the third story. It was a jury-room, and one of several which the County of Suffolk had leased to the United States for the accommodation of the federal courts. As Massachusetts had prohibited the use of her prisons and jails for the confinement of fugitive slaves, the jury- room had been converted into a cell for that purpose. The bars were placed across the door on the occasion of Sims' arrest. Immediately after the extradition of Burns, the United States received a notice to quit the premises in thirty days, which was done, and the federal courts were removed to a private dwelling temporarily fitted up. The iron bars with their fastenings were removed, and the room was afterwards partially destroyed, (perhaps purified also,) by a fire that seriously threatened the destruction of the whole building.) Had the assailants succeeded in clearing their way through all other opposition, this formidable barrier alone was sufficient to have held them in check until the arrival of a military force.

In another part of the building, the judges of the Supreme Court of Massachusetts were assembled at the same hour, awaiting the return of a jury. Some of the latter having incautiously put their heads out of the window to ascertain the nature of the tumult, were fired at indiscriminately, to the serious danger of their lives.

In the City Hall, hard by, the Mayor, with several officers of the municipal government, happened to be present at the same hour. Notified by the Chief of Police of the state of affairs, he at once ordered out two companies of artillery. Both arrived on the ground before midnight, and were stationed, the one in the Court House, the other in the City Hall. At the same time, the Marshal dispatched his deputy to procure a body of United States troops. Proceeding to East Boston, the deputy there chartered a steamer, directed his course with all speed to Fort Warren, and took on board a corps of marines under command of Maj. S. C. Ridgley. In six hours after, they were quartered within the walls of the Court House. Another company of marines was dispatched from the Navy Yard in Charlestown, on the requisition of the Marshal, and was also quartered in the same building.