CHAPTER VIII.

THE SURRENDER

(from Anthony Burns: A History by Charles Emery Stevens, 1856)

BEFORE ten o'clock the decision had been pronounced. The act of rendition alone remained to be accomplished. It was the most momentous part of the whole transaction. In a community proverbially devoted to law and order, it had become perilous to attempt the execution of such a judicial sentence. The fact that a similar sentence had once before been executed in the same community, so far from making a repetition of the act more easy, only made it more difficult. But the difficulties had been immeasurably increased by the passage of the Nebraska Bill. All through the winter and spring, the people of Massachusetts had been kept at fever heat by the debates in Congress upon that daring and Union-shattering measure. While the trial of Burns was going on, came the news of its passage through both Houses. On the day before his extradition, the telegraph announced that the bill had received the President's signature, and had become the supreme law of the land. At such a juncture, the thrice and four times odious fugitive slave law had demanded another victim. It seemed like adding insult to injury. At the moment, many regarded the arrest of Burns as a thing arranged by the Federal Government for the express purpose of showing to the country that not even the passage of the Nebraska Bill would prevent the execution of the slave law.

Excited by this state of things, the people had thronged to the trial of Burns in an unexampled manner. They came, not from Boston only, nor from suburban towns only, but from distant cities and villages of Massachusetts. Six or seven hundred went down in a body from the city of Worcester, distant forty-four miles from Boston. Many of them were men from the machine-shops and factories, whom no ordinary motive would have led to forsake their business. Day after day, during the week of the trial, the Square around the Court House had been filled by the throng; but on the last day, and when it became known that the prisoner was to be sent back, the mass of spectators was swollen to such an extent that the previous multitude seemed as nothing in comparison. Of this countless number, an overwhelming majority were bitterly hostile to the execution of the law; many had sworn that it should not be executed on that day. In the face of such a formidable popular demonstration, it now became the duty of the federal officers to remove the prisoner, a third of a mile, from the Court House to the vessel lying at the wharf.

There were two distinct objects to be accomplished,--the removal of the prisoner, and the preservation of the peace of the city. The charge of the former devolved upon the United States Marshal, that of the latter upon the Mayor of Boston. But there was danger of confounding the two objects; special care was needed to provide that, under the guise of protecting the city, the Mayor's force should not be implicated in the act of rendition. The crisis called for a magistrate who fully understood the limits of his official duty and possessed firmness enough to maintain his position. Unfortunately, the Mayor's chair was at this time occupied by one whose qualifications, natural and acquired, but ill prepared him to cope with the difficulties of his situation. Bred a physician, and transferred at once from the routine of a practitioner to the chief magistracy of the city, Mayor Smith had neither that intimate knowledge of his legal responsibilities which the crisis demanded, nor that firmness of character which would enable him to maintain a consistent course. In the outset, he had committed himself to the Faneuil Hall meeting. When the time for holding that meeting arrived, he excused himself from personally attending it, but authorized assurances to be given of his hearty sympathy. When consulted by his policemen, on the morning after the riot, he informed them that they were to render no aid to the Marshal in the rendition of Burns. Beginning thus on the side of the people, he yet ended by involving himself, the police of Boston, and the military of the Commonwealth, in the task of carrying into execution the fugitive slave act.

The arrangements were concerted and dictated by Benjamin F. Hallett, Watson Freeman, and Benjamin F. Edmands. Mr. Hallett, the leading spirit of the trio, was a politician in whom a strong desire for popularity among the masses, was constantly overmastered by a stronger desire for the patronage of the Federal Government. Accordingly, while he had made an occasional venture to secure the former, his heartiest and most persevering activity was expended in pursuit of the latter. As the reward of his devotion, not to say servility, the Government had beneficed him with the office of United States Attorney for the District of Massachusetts. This position, he seemed to imagine, gave him the right on the present occasion to direct the conduct, not only of other officers of the Federal Government, but also of the officers of the Commonwealth. Mr. Freeman, the Marshal, was a person in whom animal courage, decision, and resoluteness of purpose, were marked characteristics. Upon him devolved the sole responsibility of every step taken in the executive act of rendition. But he naturally deferred to the law officer of the Government, and his name was used to give sanction to the plans of the Attorney. Mr. Edmands was a major-general, commanding the first division of the Massachusetts Volunteer Militia. Leading the useful but inglorious life of a druggist in State Street for the most part of the time, he enjoyed the distinction of going into camp once a year, and there receiving the homage of his troops. But holiday shows of soldiery are apt to pall, and Mr. Edmands, not improbably, was ready to make the most of an occasion that promised him the novel experience of being engaged in real service. Whatever his motive, it led him into the grave indecorum of stepping out of his subordinate position as a military officer, and assuming the character of dictator to his civil superior.

Having decided upon the course to be pursued, these persons threw themselves upon the Mayor, for the purpose of coercing him into the adoption of their measures. They commenced their efforts for this end at an early stage of the trial. They sought and obtained personal interviews with him at the City Hall. They addressed to him repeated letters of remonstrance and advice. The result was, that the Mayor abandoned his first purpose, surrendered his own judgment, and conformed his official conduct to the programme which they had marked out. The correspondence which passed between the several parties clearly developed this change, and the influences by which it was effected.

From the night of the riot until the Tuesday following, two companies of the city soldiery had been under arms for the preservation of the peace. On that day, the Marshal and the Attorney addressed a formal communication to the Mayor, declaring that force to be insufficient for the purpose, and expressing the opinion that the entire command of Gen. Edmands within the city would be requisite. The Mayor's view of the case was the reverse of this. "After a full examination of the condition of the city this morning," said he, in a note to Gen. Edmands, dated May 31st, "I feel justified in saying that one military company will be amply sufficient, from this date till further orders , to maintain order and suppress any riotous proceedings."

He therefore directed Gen. Edmands to discharge one of the two companies at nine o'clock on that morning. This order was followed by another, bearing the same date, and directed to the same officer, in which, after declaring that it had been made to appear to him that a mob was threatened, the Mayor commanded Gen. Edmands to cause an entire Brigade, together with an additional corps of Cadets, to be paraded on the morning of June second, for the purpose of repressing the anticipated tumult. This sudden and extraordinary change of opinion and conduct was caused by no popular outbreak unexpectedly arising after the first order for discharging the company had been issued. The cause was suggested by Mayor Smith himself in his answers to certain interrogatories subsequently made under oath. "Mr. Hallett and Mr. Freeman called upon me," said he, "some two or three days before the second of June, and expressed an opinion that the military force then on duty was inadequate to the maintenance of the peace of the city. I was soon convinced that more force was necessary, and at once took measures accordingly." In addition to this personal interview, the Marshal and Attorney addressed to him, under date of May 31st, a joint communication in which the same views were urged upon his consideration. The interview and the despatch of the letter manifestly occurred in the interval between the issuing of the Mayor's two contradictory orders of that day. It thus appeared that while the Mayor's own careful observation of the condition of the city had convinced him that but one company of military was necessary, the representations of the United States officers convinced him, an hour or two after, that a whole Brigade was necessary.

The ostensible object of the extraordinary interference by the United States officers with the Mayor's functions, was the preservation of the peace of the city. "The Marshal does not ask any aid to execute the fugitive law as such," said that officer in his communication of May 30th; "nothing is required but the preservation of the peace of the city." "We repeat what we have before said, that the United States officers do not desire you to execute the process under the fugitive law of the United States, which devolves on them alone in the discharge of their duties; but they call upon you as the conservator of the peace of the city;"--so wrote both the District Attorney and the Marshal in their communication of May 31st. "They distinctly and explicitly declare that the United States Government neither wished nor asked any assistance from the city of Boston;"--so said the Mayor in his sworn answers at a subsequent date.

Unfortunately for this pretence, the same correspondence showed that the design was to enlist the troops of Massachusetts, in effect, though not in form, in the service of the United States. In their first communication, the two functionaries of the Federal Government, while disclaiming any authority, declared their belief that the expenses incurred by mustering the large military force which they called on the Mayor for, would be met by the President. The Mayor hesitated; their "belief" was not a sufficient guarantee. He addressed to them a note of inquiry touching that point. In the interval, Mr. Hallett, still taking the lead in another man's business, had sought and obtained from the President full authority for incurring the proposed expense. Throughout the whole affair, a frequent correspondence by telegraph was kept up between the United States officers at Boston and the President at Washington. The zeal and vigor which the Federal Executive displayed in enforcing an odious statute on this occasion, stands in striking contrast to his indifference, not to say connivance, on a later occasion, at the most high-handed violation of the Constitution and the laws. In the next communication, accordingly, the assurance of this authority, confirmed by a copy of the President's despatch, was given to the Mayor. Then immediately followed the order for mustering the Brigade. It seemed clear, therefore, on the one hand, that if, In the Mayor's judgment, there had been a real necessity for calling out a Brigade to preserve the peace of Boston, he would not have waited for an assurance that the expense would be met by a foreign government; and on the other hand, that the President would not have felt authorized to draw money from the national treasury for the purpose of preserving the peace of a municipal corporation. The sum of fourteen thousand dollars, or thereabouts, was paid out of the United States treasury to Mayor Smith, for services rendered on this occasion by the Massachusetts militia. This money was paid by him directly to the several companies, without passing into the city treasury or in any way coming under the control of the city government. No record exists at the City Hall that any such transaction ever took place. In disbursing the money, therefore, Dr. Smith acted, not in his capacity as Mayor, or as magistrate, but as an agent of the Federal Government. He supported two distinct characters in the tragedy--that of a Massachusetts magistrate in calling out the troops, and that of a Federal disbursing agent in paying them. The tenor of his note to Mr. Hallett, singularly at variance with the latter's pretences, placed the matter beyond a doubt. "Incur," said he, "any expense deemed necessary by the Marshal and yourself for city military or otherwise, to insure the execution of the law." Yielding to a requisition based upon such a document, the Mayor did, in effect, constitute the Massachusetts troops a part of the Marshal's armed posse comitatus.

The order for mustering the Brigade, which was signed by the Mayor and directed to Gen. Edmands, was drawn up by the latter officer. Distrusting his superior's knowledge of the military statutes, and confident of his own, he had assumed the task of preparing the formula that was to govern his own action. A police captain, upon entering the City Hall on the morning of June first, met Gen. Edmands descending from the Mayor's private room. As they entered the Police Office together, the military chief displayed the order with the Mayor's signature fresh upon it. "There," said he, "is the only order ever yet drawn up under which the military could legally act;" and, with some disparaging remarks on the ignorance of civilians in such matters, he proceeded to claim it as the triumph of his own genius. Then, as if for the purpose of justifying such a formidable military demonstration as that which the order contemplated, he turned and demanded of the police captain what those men were hid away for in Tremont Temple. "There are a thousand armed men there," said he. The policeman doubted the extraordinary statement. "Yes, there are," reiterated the general in a heat; "a gentleman who saw them told me; d--n them," continued he, with a profane zeal worthy of his cause, "we 'll fix 'em." The thousand men were "men in buckram."

Armed with the authority conveyed by this precept, Gen. Edmands proceeded to issue his orders for assembling the troops. At half-past eight o'clock on the morning of June second, the whole force paraded on Boston Common. It consisted of the First Battalion of Light Dragoons, the Fifth Regiment of Artillery, the Fifth Regiment of Light Infantry the Third Battalion of Light Infantry, and the corps of Cadets. In all, there were twenty-two companies, including two of cavalry, and not less than a thousand soldiers. These troops were as fine specimens of the citizen soldiery of the Union as could anywhere be found. Often had they, on parade days, attracted the admiration of their fellow-citizens by their martial bearing, the tasteful splendor of their uniforms, and the perfection of their drill. As the product of free institutions, they were held in just pride by the whole community, and never had an occasion arisen to interrupt the sympathy between the two classes. Now, for the first time, were these troops drawn up in hostile array against the people, to assist in executing the most odious statute that ever found a place in the archives of a free republic. The spectacle turned the popular complacency in their favorites into indignation and disgust.

A strong esprit du corps, together with the military maxim of unquestioning obedience, sufficed to bring out the companies with full ranks. But they were far from being unanimous in their approval of the object for which they were called forth. A keen sense of the ignominy to which they were subjected, filled the breasts of some, and caused them to hang their heads with shame. Some were indifferent to the moral character of the occasion, but were anxious to signalize their soldiership. Others sympathized with the slavehunter and rejoiced in the opportunity to render him aid with ball and bayonet. The general habits and conduct of these latter corresponded with their disposition. As they stood in line on the Common, they compromised the character of the whole corps by their free use of intoxicating liquor and the singing of ribald songs. At a later period in the day, a company or detachment posted in State street, opposite the Exchange, quite bore off the palm of infamy by conduct of this sort. Filled with liquor, even to intoxication, they became lost to all sense of decorum, and, reeling upon their gunstocks, sang the chorus, "Oh, carry me back to Old Virginny."

The character and conduct of the officers were as diverse as those of the men. Some went to the discharge of their duty, cursing the authorities who had imposed it upon them. Some pressed forward with alacrity as to congenial business. Conspicuous among the subalterns, was the commander of the Light Dragoons. His intemperate zeal for the maintenance of law on this occasion, was in striking contrast with the disposition which he manifested at a later period, when, at a convivial entertainment of the soldiery, he bade open defiance to a recently enacted statute that was intended to deprive him, and such as him, of their favorite beverages. The day did not pass without his giving in his own person a humiliating proof of the necessity of such a law. While endeavoring to ride down a nimble bystander whose sole offence was the expression of an opinion, he reeled from his saddle and fell prostrate upon the pavement.

The part to be performed by the police in the act of rendition, as well as that of the military, was prescribed by the United States officers. On the morning of Friday, June second, the Chief of the Police summoned his deputy and the captains of the several stations into his office, and locked the door. He then produced a diagram of Court Square, Court and State streets, and of the streets and avenues leading into them, together with certain written instructions, all of which he had received from the Mayor. The diagram, he informed his subordinates, represented the section of the city which was to be entirely cleared of the people and to be taken possession of by the military and police. He then proceeded to impart to the assembled captains their instructions. Among the number was Joseph K. Hayes, captain of the South Station. This officer had already acted a significant part in the business. On the morning after the attack on the Court House, he had called at the Chief's office for orders; he was directed to bring up fifteen of his men and station them in the office of the Water Registrar, opening upon the Square. Having obeyed the order, he forthwith sought the Mayor, and inquired what his men were to do.

"Are we to help the slave-catchers?" said he.

"No", replied the Mayor, "protect the property and lives of the citizens--nothing more."

Captain Hayes returned to his men and informed them of his interview with the Mayor, and of the instructions which he had received.

"Now," continued he, "I wish you distinctly to understand how much I shall help the United States in this business. If there is an attempt at a rescue, and it is likely to fail, I shall help the rescuers." In accordance with his expectation and wish, this speech was immediately reported to the Chief by some of the men under his command.

Mr. Hayes was the first to receive his instructions. He was directed to take his men, pass down State street, and notify each occupant of the buildings on the right, that by the Mayor's command they were to close their places of business. Having reached Commercial street, he was to draw up his men in a line across that street, cause them to join hands, and in that manner force back the crowd to Milk street, where he was to hold them at all hazards. Immediately after, a detachment of military was to be posted across Commercial, at its junction with State street. The whole space in Commercial street, between Milk and State streets, would thus be kept vacant. He was further instructed that, if his police force should be unable to maintain their stand against the pressure of the crowd, they were to swing back right and left; this was to be a signal to the military at the other end, who had instructions instantly, without giving warning, to fire upon the crowd.

The same instructions were repeated to the rest of the captains. Each was charged with the duty of clearing a particular street, each was to be followed by a military detachment, having orders to fire without warning.

Mr. Hayes listened attentively to this programme. "Mr. Chief," said he, "does not this look like helping to carry off Burns?" The Chief, with some embarrassment, made an indistinct reply. Just then a tap was made on the door. Upon its being opened, the Mayor entered, and bowing to those present said:

"The Commissioner has just entered the courtroom to give his decision, and has required me to see that the Square and the various avenues are cleared." Then, instructing the Chief forthwith to attend to that duty, he withdrew. Mr. Hayes again spoke:

"The Commissioner gives directions to the Mayor, the Mayor to the Chief of Police, the Chief to his captains, they to their men; this is a pretty strong chain binding us to the act of rendition."

Without further words, he retired to another room, wrote a resignation of his office, and then, entering the Mayor's private apartment, placed it in his hands. Greatly agitated, the Mayor entreated him to revoke it, but Mr. Hayes had not acted hastily, and remained immovable. Taking a copy of his resignation, he carried it to the office of one of the newspaper presses, which, during this memorable occasion, were throwing off editions at all hours of the day, and within an hour's time it was scattered over the whole city. This act, so rare in the history of official life, involved the sacrifice, not only of assured position, but also of the most flattering prospects. But it had its reward.

The resignation of Mr. Hayes seriously deranged the plans of the Mayor and his advisers. They had intended to disguise the employment of the military by pushing the police prominently forward.

The police were to clear the streets, they only were to come in contact with the people and force them back beyond the outer barrier of the reserved section. When this was complete and the space clear, the military were to march in and take up the several positions assigned them. The failure of the police to accomplish their part of the task made it necessary to call in the aid of the military. The selection of the officer to whom the business was entrusted, was significant of the influences that controlled the proceedings. This was Isaac H. Wright. He was one of the very few men of Massachusetts who had set at naught the principles of their fathers by volunteering in the war with Mexico. The fellow-officer of Gen. Pierce in that wicked raid, his equal in military skill, not less his equal in moral character, scarcely his inferior as a claimant upon his party for promotion, of congenial habits, and like him often hazarding all upon a powerful flow of spirits, he was yet, unlike him, made to feel full sorely the caprice of Democracy in the distribution of political favors. For while Gen. Pierce, returning from the plains of Mexico, had been wafted into the Presidential Chair by prosperous winds blowing from all quarters, Col. Wright was left to exchange the sword for the hammer and to settle down into the humdrum life of an auctioneer. He was now, however, the captain of the Light Dragoons, and no officer in all the Massachusetts troops was more ready to assist in the execution of the fugitive slave act than himself. In committing to him and his mounted Dragoons the duty of driving the citizens from their thoroughfares and places of business, the authorities could not expect that any tenderness would temper their zeal.

In the midst of these preparations, the city was electrified by the following proclamation which was posted at the comers of the streets:

TO THE CITIZENS OF BOSTON:

To secure order throughout the city this day, Major-General Edmands and the Chief of Police will make such disposition of the respective forces under their commands as will best promote that important object; and they are clothed with full discretionary power to sustain the laws of the land. All well-disposed citizens and other persons are urgently requested to leave those streets which it may be found necessary to clear temporarily, and under no circumstances to obstruct or molest any officer, civil or military, in the lawful discharge of his duty. V. C. SMITH, Mayor. BOSTON, June 2,1854.

By this proclamation the whole city was in effect placed under martial law. It notified the citizens that the Mayor had, for the time, delegated his power to a military officer and abdicated his office. The legality of this step was afterward seriously called in question. Among others who took this ground, was Peleg W. Chandler, then a member of the Executive Council of the Commonwealth, and previously, Solicitor for the city of Boston. In an argument that never was refuted, he examined the Mayor's whole course in relation to the military, and maintained that in several particulars he had acted without warrant of law.

About eleven o'clock, the troops on the Common received orders to move down into Court and State streets. Each man had been supplied with eleven rounds of powder and ball, and, before moving, they proceeded to load in the presence of the assembled spectators. Then, without music, they marched down through the above-named streets, dropping off detachments at the several side streets, until the whole were posted.

Meanwhile, the Marshal had been making his own preparations. One hundred and twenty-five men were sworn in as specials. Some of these were tide-waiters, truckmen, and other dependents upon the Custom House; all were taken from the least reputable portion of the citizens of Boston. No better could be obtained. So great had been the change in public opinion since the extradition of Sims, when merchants, bankers, ship- owners, and others of repute had pressed forward with offers of personal service in forcing back that hapless negro into slavery and death. These specials were assembled in the Court House, and armed with cutlasses, pistols, and billies. They were then placed under the command of one Peter T. Dunbar, a Custom House truckman, who led them into an upper hall of the building, and there drilled them in marching and other exercises before the door of Burns's cell. Besides these, the Marshal had assembled five companies of United States troops, numbering one hundred and forty men; and, to complete his array, a brass cannon had been transported from the Navy Yard in Charlestown, at early dawn, and planted in the Square.

At eleven o'clock, Court Square presented a spectacle that became indelibly engraved upon the memories of men. The people had been swept out of the Square, and stood crowded together in Court street, presenting to the eye a solid rampart of living beings. At the eastern door of the Court House, stood the cannon, loaded, and with its mouth pointed full upon the compact mass. By its side stood the officer commanding the detachment of United States troops, gazing with steady composure in the same direction. It was the first time that the armed power of the United States had ever been arrayed against the people of Massachusetts. Men who witnessed the sight, and reflected upon its cause, were made painfully to recognize the fact, before unfelt, that they were the subjects of two governments.

After the decision, Burns remained in the courtroom awaiting the hour of his departure. The retainers of the Marshal crowded around him with attempts at consolation. His guards especially endeavored to cheer his spirits. They gave him four dollars; they assured him that it was their intention to purchase his freedom; they had made arrangements with his owner, they said, and had already obtained four hundred dollars toward the object. To all these professions and promises Burns paid little heed; they came from the same men who had captured him. At length, Deputy Marshal Riley entered the room and ordered him to be handcuffed. Burns earnestly remonstrated against the indignity; he gave assurances that he would pass through the streets quietly, if allowed to go unshackled, otherwise, he threatened to make every demonstration of violence in his power. Butman thereupon left the room, and sought the Marshal's permission to dispense with the instruments of disgrace; and, in spite of counsel to the contrary from some cowardly adviser who stood by, the request was granted. The slavery into which Burns was returning was an evil which he had borne from the cradle, but the iron fetters were symbols of disgrace which his unbroken spirit was not prepared to endure.

One o'clock had arrived, and yet the movement of the cortege was delayed. Meanwhile, Gen. Edmands had from time to time dashed into the Square, and, dismounting, held hurried conferences with the Marshal in the building. A bystander who heard their conversation, learned that the delay was caused by the General's inability to clear the streets, and his fear of being unable to accomplish the task he had undertaken.

At length, about two o'clock, the column was formed in the Square. First came a detachment of United States Artillery, followed by a platoon of United States Marines. After these followed the armed civil posse of the Marshal, to which succeeded two platoons of Marines. The cannon, guarded by another platoon of Marines, brought up the rear. When this arrangement was completed, Burns, accompanied by a officer on each side with arms interlocked, was conducted from his prison through a passage lined with soldiers, and placed in the centre of the armed posse. Immediately after the decision, Mr. Dana and Mr. Grimes had asked permission to walk with Burn's arm in arm, from the Court House to the vessel at the wharf; and the Marshal had given them his consent. At the last moment, he sought them out and requested that they would not insist upon the performance of his promise, because, in the opinion of some of the military officers, such a spectacle would add to the excitement. Mr. Dana declined to release the Marshal from his promise. The latter persisted in urging the abandonment of the purpose.

"Do I understand you," asked Mr. Dana, "to say distinctly that we shall not accompany Burns, after having given your promise that we might?"

The Marshal winced under the pressure of this pointed question, but after a momentary reluctance answered firmly, "Yes." Accordingly, without a single friend at his side, and hemmed in by a thickset hedge of gleaming blades, Burns took his departure.

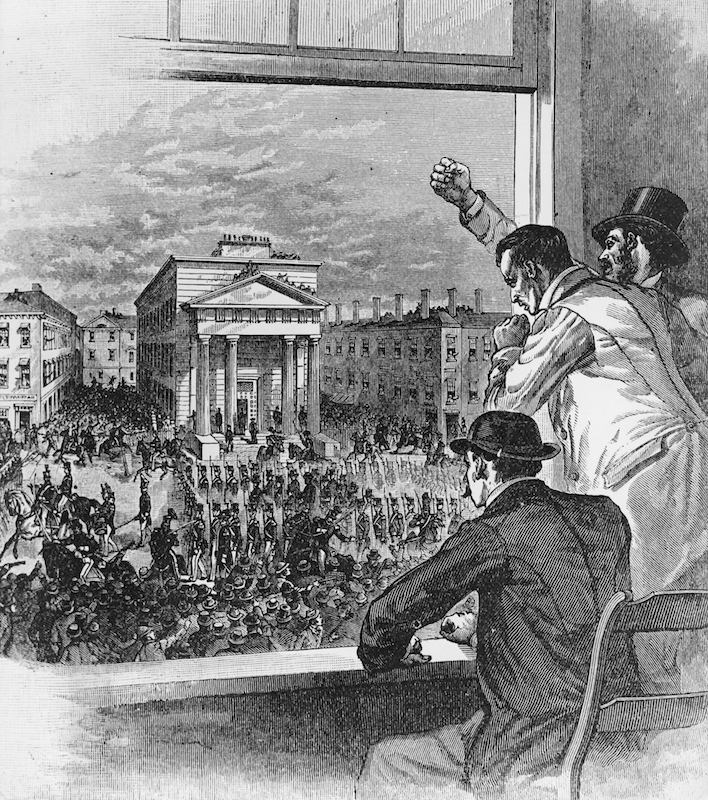

The route from the Court House to the wharf had by this time become thronged with a countless multitude. It seemed as if the whole population of the city had been concentrated upon this narrow space. In vain the military and police had attempted to clear the streets; the carriage-way alone was kept vacant. On the sidewalks in Court and State streets, every available spot was occupied; all the passages, windows, and balconies, from basement to attic, overflowed with gazers, while the roofs of the buildings were black with human beings. It was computed that not less than fifty thousand people had gathered to witness the spectacle.

At different points along the route, were displayed symbols significant of the prevailing sentiment. A distinguished member of the Suffolk Bar, whose office was directly opposite the courtroom, and who was, at the time, commander of the Ancient and Honorable Artillery, draped his windows in mourning. The example was quickly followed by others. From a window opposite the Old State House, was suspended a black coffin, upon which was the legend, The Funeral of Liberty. At a point farther on toward the wharf, a venerable merchant had caused a rope to be stretched from his own warehouse across State street to an opposite point, and the American flag, draped in mourning, to be suspended therefrom with the union down. On looking forth from his window some time after, he saw a man intent on casting a cord over the rope, for the purpose of tearing down the flag.

"Rascal!" shouted the old man, as he sallied forth with his long white hair streaming behind, "desist, or I'll prosecute you."

"I am an American," answered the other, "and am not going to see the flag of. my country disgraced."

"I too am an American, and a native of this city," retorted the State street merchant, "and I declare that my country is eternally disgraced by this day's proceedings. That flag hangs there by my orders: touch it at your peril." The flag remained, until the transaction of which, in its dishonor, it was a fit emblem, was fully ended.

Along this Via Dolorosa, with its cloud of witnesses, the column now began to move. No music enlivened its march; the dull tramp of the soldiers on the rocky pavements, and the groans and hisses of the bystanders, were the only sounds. As it proceeded, its numbers were swelled by unexpected additions. Unauthorized, the zealous commander of the mounted Dragoons joined it with his corps. The Lancers, jealous of their rivals, hastened to follow the example: thus vanguard and rear-guard consisted of Massachusetts troops. In its progress, it went past the Old State House, where, in 1646, the founders of the Commonwealth enacted that solemn condemnation of human slavery, which stands at the beginning of this volume.Just below, it passed over the ground where, in the Massacre of 1770, fell Attucks, the first negro martyr in the cause of American liberty.

Opposite the Custom House, the column turned at a right angle into another street. This cross movement suddenly checked the long line of spectators which had been pressing down, State street, parallel with the other body; but the rear portion, not understanding the nature of the obstruction, continued to press forward, and forced the front from the sidewalk into the middle of the Street. To the chafed and watchful military, this movement wore the aspect of an assault on the cortege; instantly some Lancers, stationed near, rode their horses furiously at the surging crowd, and hacked with their sabres upon the defenceless heads within their reach. Immediately after, a detachment of infantry charged upon the dense mass, at a run, with fixed bayonets. Some were pitched headlong down the cellar-ways, some were forced into the passages, and up flights of stairs, and others were overthrown upon the pavement, bruised and wounded.

The assaults of the soldiers on the bystanders resulted in serious injury to several persons. One, A. L. Haskell, was attacked by Capt. Evans with a drawn sword, and cut on the back of the hand, for hissing and crying "shame." Holding up to view his bleeding hand, Mr. Haskell asked the officer his name and business. Capt. Evans gave his name, and to the inquiry touching his business, replied, "to kill just such d--d rascals as you are." A man named John Milton had his head laid open by a sabre cut, and was borne off to the hospital, where he lay for several weeks. But the most aggravated case was that of William H. Ela. While attempting to proceed quietly about his own business, he was assaulted by soldiers; beaten on the head with muskets; cut and bruised in the face; knocked down upon the pavement; and finally carried off and placed in confinement. These injuries impaired his mind to such an extent, that he was unable to go on with the business in which he was previously engaged, and which was his chief dependence for a livelihood. He afterward brought an action against Mayor Smith and others, for the assault, which became important as testing a question of law, and also as bringing to light material facts relating to the extradition of Burns.

While this was passing, the procession moved on and reached the wharf. A breach of trust had secured to the Federal authorities the use of this wharf for their present purpose. It was the property of a company, by whom it had been committed in charge to an agent. Without their knowledge and against their wishes, he had granted to the Marshal its use on this occasion. When arraigned afterward by his employers for such betrayal of trust, he replied that he had since been rewarded by an appointment to a place in the Custom House.

At the end of the wharf lay a small steamer which had been chartered by the United States Government. On board this vessel Burns was conducted by the Marshal, and immediately withdrawn from the sight of the gazing thousands into the cabin below. The United States troops followed and, after an hour's delay, the cannon was also shipped. At twenty minutes past three, o'clock, the steamer left the wharf, and went down the harbor.