CHAPTER XI.

THE RANSOMED FREEDMAN (from Anthony Burns: A History by Charles E. Stevens, 1856)

At Rocky Mount, Burns entered on the last stage of his life as a slave. He was there introduced to new scenes and subjected to new influences. His new master was a different person from Col. Suttle. He possessed a more marked character, and a far greater capacity for business. In person he was short but stout, with a large head, and a countenance indicative of firmness, courage, and decision. He had an iron will that was made the law for all within his sphere; but he could appreciate and honor manly qualities in others. While his sharp, stern style of address would cause most persons to shrink away, he was not displeased when any one had the courage to stand up and confront him with manly self-assertion. Though he practically manifested but little respect for the decalogue, he made it a point of honor to fulfill his engagements.

The business of Mr. McDaniel was that of a planter, slave-trader, and horse-dealer combined. He possessed an extensive plantation, which was chiefly devoted to the culture of cotton. For the management of this, he kept constantly in his service

Page 199

a large body of slaves. The number of these was constantly changing. Sometimes there would be as many as one hundred and fifty on the plantation at once; sometimes not more than seventy-five. This fluctuation was owing to the purchase and sale that was constantly going on. The plantation was made subservient to the slave-trading, The slaves were always for sale, but, while waiting for customers, they were kept at work instead of lying idle in barracoons. When a customer offered, he was accommodated, and when the stock ran low, it was replenished.

The domestic relations of McDaniel were in keeping with his character and pursuits. His wife stood in great fear of him. She presided over his household, but neither inspired nor enjoyed his respect. The tender bond of children was also wanting between them. He kept a harem of black girls, and took no pains to conceal the fact from his wife. By some of these, children were born to him, but, true to his instincts as a slave-trader, he made merchandise of them and their mothers without compunction.

The post which was assigned to Burns by his new owner was that of coachman and stable-keeper. As a horse-dealer, McDaniel kept on hand a large stock of horses and mules, often as many as a hundred at once. The stables of these animals were placed under the charge of Burns, and he held the keys. But he was required to groom and serve only the carriage-horses and his master's

Page 200

filly; the rest of the animals were cared for by other slaves. Whenever his mistress was inclined to take an airing, or visit a neighbor, or ride to church, it devolved on him to drive her carriage. The whole service which he was thus required to perform was light and pleasant.

His personal accommodations were better than they had ever been before. Instead of being compelled to turn in with the slaves at their quarters, he had a lodging assigned him in an office, and partook of his meals in the master's house. He was allowed to obtain what he wanted at a store of which McDaniel was the proprietor. His religious privileges were less attended to. Twice only, during his four months' servitude, was he able to attend church on Sunday. Whenever he drove his mistress to church, which was not often, he was required to wait with the horses outside while she worshipped within. It has been seen that he refused to give his owner a pledge to refrain from preaching among the slaves. In this he was governed by a sense of duty. He had been regularly invested with the office of a slave-preacher, and it was his purpose to exercise it as he had opportunity. Accordingly, during his period of service with McDaniel, he succeeded in holding, at various times, six or eight preaching-meetings among the slaves on the plantation. Once he was discovered, but his master chose to take no notice of the offence. The manliness and general good disposition of Burns so won his regard,

Page 201

that he tolerated in him what he would have punished in another. On his part, Burns was deeply impressed by the liberal treatment of his master, and he subsequently declared that he could not, in conscience, have run away so long as it continued. It was a matter of special favor that he was not placed under the control of an overseer, but was held accountable only to his master. The office in which he lodged was shared with him by one of the overseers. This equality of their condition, or some other cause, impelled the overseer to pick a quarrel with Burns, and he carried it so far as once to draw a pistol upon him. Burns made complaint of the assault to McDaniel, from whom, in consequence, the overseer received a stern rebuke.

His relations with his mistress were less agreeable. In striving to please his master he displeased her. McDaniel had given him express instructions to pay no heed to her commands, if they conflicted with his own. Once, in his absence, she demanded of Burns his master's favorite saddle-horse for her own use. On his refusing, she took the animal and rode off. In the mean time, McDaniel returned, and, finding what had happened, gave his wife a severe reprimand and justified Burns.

Buried thus in the obscurities of slavery, Anthony remained for some months wholly lost to the knowledge of his northern friends. All efforts on their part to discover his retreat were fruitless. On the other hand, several letters which he had

Page 202

written to them, and which would have imparted the desired information, never reached their destination; probably they were never suffered to leave the post-office in which he had deposited them. At length, an accident revealed the place of his abode. He had one day driven his mistress in her carriage to the house of a neighbor, and, while sitting on the box, was pointed out to the family as the slave whose case had excited such commotion throughout the country. It chanced that a young lady residing in the family heard the statement, and by her it was repeated in a letter to her sister in Massachusetts. By the latter the story was related in a social circle where the Rev. G. S. Stockwell, one of the clergymen of the place, happened to be present. This person immediately addressed a letter to Anthony's owner, inquiring if the slave could be purchased. An answer was promptly returned that he might be purchased for thirteen hundred dollars. This information was communicated to Mr. Grimes, accompanied by a declaration that it was the purpose of the clergyman to free Anthony, and also by an inquiry as to the amount of money which could be obtained in Boston for the purpose. Mr. Grimes returned answer, after making some inquiry of former subscribers, that he thought one half of the sum might be obtained in Boston. It was accordingly agreed that the labor of obtaining the whole amount should be equally divided between the two. A fortnight after, however, Mr. Stockwell wrote Mr. Grimes

Page 203

that he should try to secure seventy-five dollars for expenses, and urged Mr. Grimes to get the thirteen hundred dollars as soon as possible. Thus the whole responsibility of the affair was once more thrown upon Mr. Grimes.

It was not by accident that this man became a chief actor in the transactions narrated in this volume. His life had been consecrated to this sort of service, and he was now only continuing what he had long before begun. An outline of his previous history will be a proper introduction to the account of his further, and, as the event proved, successful, efforts for the liberation of Anthony Burns.

Born in Virginia in the midst of slavery, though of free parents, Leonard A. Grimes was yet slightly connected by blood with the oppressed race. Left an orphan at the age of ten years, he was placed in the charge of an uncle, but the new home did not prove to be a pleasant one. Being taken to his native place on a visit, he refused again to become an inmate of his uncle's family, and soon after went to reside in Washington. There he passed several years of his life, first in the capacity of a butcher's boy standing in the public market, and subsequently as an apothecary's clerk. At length he attracted the favorable regards of a slaveholder, into whose service he was persuaded to enter upon hire. He became the confidential agent of his employer, and a deserved favorite with all the members of his family. But neither

Page 204

gratitude for kindness, nor love of gain, could induce him to become a participator in the great wrong of slavery. Offered the post of overseer, which had become vacant, with a salary tenfold his pay, he did not hesitate to refuse it. Far enough from any taint of abolitionism at the time, a sort of unconscious abhorrence of slavery preserved him from the contamination.

The business of his employer often led him on long journeys through the southern States, when he was accompanied by young Grimes. On one of these occasions, as they were riding through a patch of forest in North Carolina, the screams of a woman pierced their ears. On gaining the open country, they beheld near the road-side a female slave naked to the waist, and by her side an overseer lashing her with his heavy thong. The dark surface of her back was already barred with broad red stripes, while the blood poured down her limbs and stood in little pools at her feet. The employer of Grimes was a humane man, though a slaveholder, and his blood boiled at the sight. Drawing a pistol, and riding up to the miscreant, he ordered him to desist or he would instantly shoot him through. The overseer sullenly replied that he was punishing the woman because she had come late to her work. "My baby was dying, and will be dead before I see it again," interposed the wretched mother by way of excuse. She was roughly ordered off to her work, and the slaveholder,

Page 205

still keeping a vigilant eye on the movements of the overseer, rode on his way.

This scene wrought a revolution in young Grimes. It was his first vision of the bloody horrors of slavery, and it made him the uncompromising and life-long foe of that atrocious institution. Until now he had never been led to reflect upon the true character of the institution of slavery in the midst of which he had been born and nurtured. The sight of the bleeding mother, in her double agony of separation from her dying child and of ignominious torture in her own person, produced a shock that threw wide open his eyes and forever dispelled his indifference. His physical system became disordered; "I grew sick," said he, "and felt a sensation as of water running off my bowels. I longed for permission from my employer to shoot the man dead."

Returning home, he soon had an opportunity to put in practice the new purpose of his heart. A female slave on a neighboring plantation had received from an overseer thirty lashes for attending a religious meeting, and had fled to the estate of Grimes's employer, one of whose slaves was her husband. The case was brought to the knowledge of Grimes, and by him she was soon put upon the road to Canada, whither her husband shortly followed her. This was his induction into an office in which he afterward made full proof of his ministry to those in bondage.

Leaving his employer's service, he purchased,

Page 206

with his carefully saved earnings, one or two carriages and horses, and set himself up in business as a hackman in the city of Washington. Prosperity attended him; carriage was added to carriage, and horse to horse, until he became one of the foremost in his line of business. Thus he went on for twelve years, and while his coaches were in constant requisition by the gentry of the capital, they were not seldom placed at the service of the fugitive from southern bondage. The slaveholder oftentimes pressed the seat that perhaps the day before had been occupied by the flying slave.

At length a crisis came. The wife and seven children of a free negro were about to be sold by their master to a southern slave trader, and sent to the far south. In his distress, the husband and father applied to the man who kept coaches and horses for the use of fugitive slaves. Mr. Grimes was not backward to listen to his cry. Under the cover of a single night's darkness, he penetrated thirty miles into Virginia, brought off the whole imperilled family, and while the owner's posse, in hot pursuit, were, five hours later, blindly groping after them in Washington, they passed in disguise almost before the hunters' faces on their way to the northern land of freedom. Three months after, Mr. Grimes was arrested, taken into Virginia, and tried for his offence. The jury found him guilty, not however in accordance with the evidence, which totally failed, but to save their own lives and the life of the prisoner from an infuriated mob

Page 207

that had surrounded the Court House during the whole trial, and had only been kept from invading the hall of justice and committing murder by the presence of a strong military force. Sentenced to hard labor for two years in the State prison at Richmond, he there, through the instrumentality of a godly slave, (temporarily placed there for safe keeping and not for crime), experienced that great spiritual change which makes all things new for the soul. Like Paul, he straightway preached Jesus, and within two months, five of the prisoners were made partakers with him of that freedom wherewith Christ maketh free. Returning to Washington at the expiration of his sentence, he prudently abandoned the now, for him, suspicious business of a hackman, and contented himself with the humbler employment of jobbing about the city with a "furniture car." Having been admitted into the visible church, he ere long felt a divine impulse to preach the gospel. After due examination by a council of which the President of Columbian College was moderator, he received license to preach. Without abandoning the business of jobbing, he exercised his gift of preaching as opportunity offered. But the atmosphere of Washington did not permit him to breathe freely, and he sought a home in a free State.

Coming to Boston, he found there many fugitive slaves, wandering as sheep without a shepherd. He gathered them into a large upper room and preached to them the gospel. They entreated him

Page 208

to remain and minister to them. He consented; attendants on his ministry multiplied., and soon a church of fugitive slaves was organized in the metropolis of New England. The upper room became too strait for them, and, through the zeal and energy of Mr. Grimes, a commodious and handsome structure began to rise from its foundations. Then came the fugitive slave act, pouring ruin on this thriving exotic from the south. The church was arrested midway toward its completion, and the members were scattered in wild dismay. More than forty fled to Canada. One of their number, Shadrach, was seized, but, more fortunate than the hapless Sims, who had no fellowship with them, he succeeded in making good his escape. When the first fury of the storm had blown over, Mr. Grimes set himself with redoubled energy to repair the wastes that had been made. He collected money from the charitable, and purchased the members of his church out of slavery that they might return without fear to the fold. He made friends among the rich, who advanced funds for the completion of his church. At length it was finished, and, as if for an omen of good, was dedicated on the first day when Burns stood for trial before Mr. Commissioner Loring.1

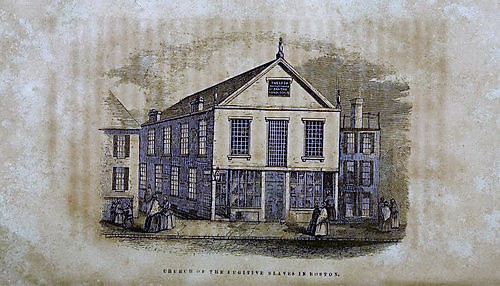

1 The church is a neat and commodious brick structure, two stories in height, and handsomely finished in the interior. It will seat five or six hundred people. The whole cost, including the land, was $13,000, of which, through the exertions of Mr. Grimes, $10,000 have already been paid. The engraving is an accurate representation of its appearance.

CHURCH OF THE FUGITIVE SLAVES IN BOSTON.

Page 209

In now devoting himself to the ransom of this last victim of the oppressor, he but added one more to the long list of acts that had given character to his whole life.

Finding the business on his hands, Mr. Grimes proceeded to prompt and energetic action. His first care was to have Mr. McDaniel informed that his terms were accepted; and an appointment was made to meet him with Anthony in Baltimore on the twenty-seventh of February, and there complete the negotiation. He then laid the subject before the Baptist clergy of Boston at their weekly meeting. Most of them entered warmly into his plan and engaged to take up collections in their several churches. The same course was pursued toward the clergy of other denominations with various degrees of success. From these sources, about three hundred dollars were obtained. Three of the old subscribers redeemed their pledges by the payment of one hundred dollars each; and smaller sums were obtained from other persons of less means. When the day for his departure for Baltimore arrived, Mr. Grimes had succeeded in collecting only six hundred and seventy-six dollars. At the last moment, it seemed likely that the plan would fall through. The whole sum must be taken to Baltimore, and Mr. Grimes had no means of his own to make good the deficiency. The time bad been fixed, McDaniel would be on the spot, and finding no purchaser, would depart in a state of irritation and sell Anthony to go south, as he

Page 210

had already threatened in one of his letters. In this emergency, the friendly cashier of a Boston bank stepped in to Mr. Grimes's relief. He received the amount already collected, accepted the note of Mr. Grimes for the balance, and placed in his hands a cheque on a Baltimore bank for thirteen hundred dollars. Thus furnished, Mr. Grimes took his departure for the Monumental city. it had been agreed that he should be accompanied by Mr. Stockwell, but, through some misunderstanding, the latter failed to appear at the place and time appointed. Mr. Grimes proceeded alone, and at eleven o'clock on the twenty-seventh of February arrived at Barnum's Hotel in Baltimore.

Meanwhile, McDaniel had broken the subject to Anthony. On receiving the first letter from Mr. Stockwell, he asked the slave if he had been writing letters to the North. Anthony evaded the question. McDaniel then informed him of Mr. Stockwell's proposition to purchase him, and inquired if he would like to have his freedom. Burns hesitated to answer, fearing that he should be entrapped. He asked permission to look at the letter, which was readily granted. Finding that McDaniel had truthfully represented the matter, he then frankly avowed his desire to be free and go to the North. Nothing more passed until the letter was received which announced the acceptance of McDaniel's terms and fixed the day of meeting in Baltimore. Soon after, Anthony drove his master to the railroad station for the purpose of taking the train to Richmond.

Page 211

On alighting, Mr. McDaniel paced the ground to and fro, absorbed in thought. At length he addressed Anthony:

"I am going to tell you a secret; you must communicate it to no one, not even to my wife; what do you think it is?" continued he, after a pause.

Anthony professed that he could not imagine, unless it was that some news had come from the North. McDaniel then informed him of the happy prospect before him, and, directing him to be in readiness to depart for Baltimore on the following Monday, once more repeated his injunction of secrecy. It was at no small risk to himself that he was about to set at defiance the public sentiment of the South by sending Anthony back to the North.

Monday morning found master and slave on their journey northward by rail. Before they had proceeded ten miles, McDaniel's apprehensions were realized. Through the carelessness or treachery of a friend whom McDaniel had made a confidant, it became known that the obnoxious fugitive was on board. The passengers were quickly in a tumult, and it was proposed to stop the train and put the "boy" out. The conductor protested that had he known in the outset who Anthony was he would not have permitted him to enter the cars at all. The firmness of McDaniel, however, held the mob spirit in check, and Anthony was at length suffered to proceed without further molestation.

On arriving at Norfolk, they immediately went on board the steamer bound for Baltimore. Leaving

Page 212

Burns in the vessel, McDaniel went back into the city to transact some business. Meantime, the mischievous passengers of the railroad train had circulated the news of Anthony's presence. The waspish little city was at once thrown into angry commotion and forthwith swarmed in a body on board the vessel. There, on returning soon after, McDaniel found his man Anthony surrounded by the chivalry of Norfolk, and half dead through fear of their threatened violence. Sending him below deck, McDaniel faced the excited throng. They demanded that he should forego his purpose, and offered him fifteen hundred dollars for his slave. He declined the offer. They then pressed him to name his own price. His reply was that he had agreed to take Burns to Baltimore, and he intended to keep his word if it cost him his life. They then attempted to move him by intimidation, but this only roused his spirit. For an hour and a half, with pistol in hand, he kept them at bay. At last, he was allowed to depart on giving assurance that if the Massachusetts purchasers failed to keep their appointment, he would immediately return and dispose of Burns at Norfolk.

Without further molestation they pursued their way to Baltimore, and arrived at Barnum's Hotel about two hours after Mr. Grimes. The latter was absent at the moment, but, returning shortly after, was immediately ushered into the private apartment where the two travellers were secluded. Anthony greeted him with a face all radiant with

Page 213

happiness, and then, turning to his owner, exclaimed, "I told you it must be Mr. Grimes." In explanation of this, McDaniel said that Burns had constantly maintained, notwithstanding the correspondence had been conducted by Mr. Stockwell, that Mr. Grimes would be found at the bottom of the efforts for his liberation.

Negotiations were at once commenced. Mr. Grimes produced his cheque on the Baltimore bank, but the cautious slave trader required the cash. Accordingly, Mr. Grimes went to the bank to get the cheque cashed, but found to his annoyance that, by a rule of the institution, some citizen of Baltimore was required to certify that he was the person named in the cheque. He was unknown to a single individual in the city. From this dilemma he was relieved by the kindly aid of the landlord, Barnum. The cheque was indorsed to McDaniel, Barnum made the necessary certification in his behalf, and the cash was obtained. Before signing the bill of sale, the thrifty slave trader required an additional sum of twenty-five dollars to defray his expenses. Remonstrance was unavailing, and it was paid. The transaction being completed, Mr. Grimes pleaded with McDaniel to make Anthony a present of a hundred dollars with which to begin his new life; but the plea was met by the reply that twice that amount had already been sacrificed in keeping the engagement.

By this time a rumor of Burns's presence had got into circulation, and some feeling began to be displayed

Page 214

among the people in the hotel. Mr. Grimes, in consequence, decided at once to leave the city. As he and Burns passed out of the hotel, they met, upon the threshhold, Mr. Stockwell, who had that moment arrived. Finding the business completed, he turned and accompanied them back to the railway station. There they encountered another of the thousand safeguards erected by slavery, for its protection, at the expense of perpetual vexation to freemen. This was a regulation of the railroad company requiring a bond of one thousand dollars to hold the company harmless for carrying negroes. Through the friendly offices of Mr. Barnum, who signed the instrument, this obstacle was surmounted; the train then whirled off, the land of bondage was forever left behind, and that night Anthony Bums slept in Philadelphia, a free man upon free soil.

From this period he entered upon his career as a citizen of the United States, equal in the eye of the law to his former owners, and entitled to all the immunities and privileges which they could claim. But, though invested with this high title, it was practically of little or no avail to him throughout one half of the Union. It was true that the Constitution more unequivocally guarantied his protection as a freeman than his restoration as a slave; but all experience had shown it to be also true that this guaranty was for him, and such as him, worth absolutely nothing. With a solemn constitutional pledge that he should be protected in the enjoyment

Page 215

of all rights of citizenship while sojourning anywhere within the domain of the Union, he yet could not venture to set foot again upon the soil of his native state. Henceforth the only home for him was in the North.

On the day following his manumission he proceeded to New York, and, in a public assembly which was gathered to welcome him, narrated his story. Early in March he repaired to Boston, where preparations had been made to give him a public reception and congratulate him on the recovery of his freedom. A large meeting was held in Tremont Temple, and there, surrounded by many clergymen, and others of note, Burns stood forth upon the platform and repeated his tale of outrage and suffering. His manly address, the sobriety of his speech, and the degree of intelligence which he manifested, took his audience by surprise and won for him increased respect. "Burns is more of a man than I had supposed," said the Rev. Mr. Kirk in his address on the occasion; "he has spoken to my heart to-night like a man. He has the true oratorical ring in him, like that of some of the Indian orators."

This meeting was followed by others of a like character in various parts of the Commonwealth. The people were eager to see the man whose enforced return to slavery had so convulsed the State. Nor did they fail to accompany the gratification of their curiosity with substantial tokens of their sympathy. It was far from Anthony's wish or intention,

Page 216

however, to gain a livelihood by making merchandize of his wrongs.1

1 Immediately after Burns recovered his freedom, the great showman, Barnum, addressed a letter to one of his friends offering him $500 if he would take his stand in the Museum at New York, and repeat his story to visitors for five weeks. When Burns was made to comprehend the nature of this proposal, he rejected it with indignation. "He wants to show me like a monkey!" said Burns.

The calling to which he had devoted himself while a slave, he was more than ever bent on pursuing now that he had become a freeman. He still felt it to be his duty and desire to preach the gospel. This decision received the approval of his friends, and they took measures to promote his design. To qualify him for the sacred office, it was necessary that he should pass through a complete course of study. A lady of Boston, who held a scholarship in the Institution at Oberlin, offered to place him on that foundation. This offer was gratefully accepted, and early in the summer of 1855, he entered upon his studies in that Institution.

Soon after taking up his residence at Oberlin, he addressed a note to his old pastor in Virginia, requesting a letter of dismission and general recommendation from the church of which he had been a member while in bondage. To this request no direct answer was ever returned. But it served, apparently, to remind pastor and church of the great neglect of duty toward the institution of slavery of which they had been guilty; and they proceeded to repair that neglect by excommunicating Burns, for "disobeying both the laws of God

Page 217

and man by absconding from the service of his master and refusing to return voluntarily." Four months after, he received a copy of a newspaper containing a communication signed by the pastor and addressed to himself. It included the sentence of excommunication, and a defence of slavery drawn from the New Testament by the pastor, together with a rebuke of all christian anti- slavery men. To this communication Burns published an answer, which showed not only his ability to cope with the Virginia pastor in argument, but also his progress in a sound interpretation of the Bible.

Thus by the hand of unchristian rudenesss was severed the last tie that connected Anthony Burns with the land of bondage.