The Dreyfus Affair Trials

The Court-Marial of Alfred Dreyfus

by Douglas O. Linder (2020)

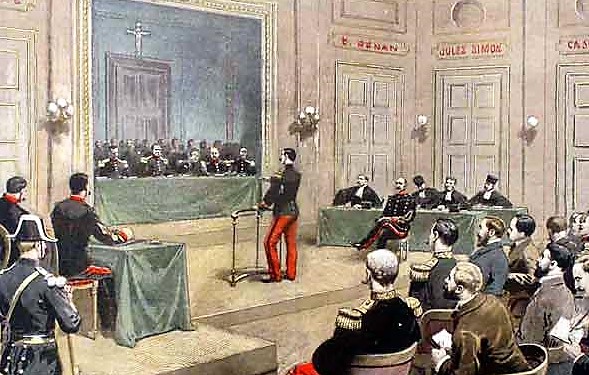

Scene from Dreyfus's 1899 court-martial in Rennes

Madame Marie Bastian became the most important cleaning woman in history by simply doing her job—as an agent of the Statistics Section, the intelligence unit of the French Army’s General Staff. Bastian worked at the German Embassy in Paris, where one of her duties was to empty the wastebasket of the German military attaché, Lieutenant Colonel Maximillian Von Schwartzkoppen, and throw the contents in the furnace. Instead, Bastian delivered whatever she gathered from the wastebasket to Major Hubert-Joseph Henry in the Statistics Section, who would sift through the papers for anything of potential interest to French intelligence.

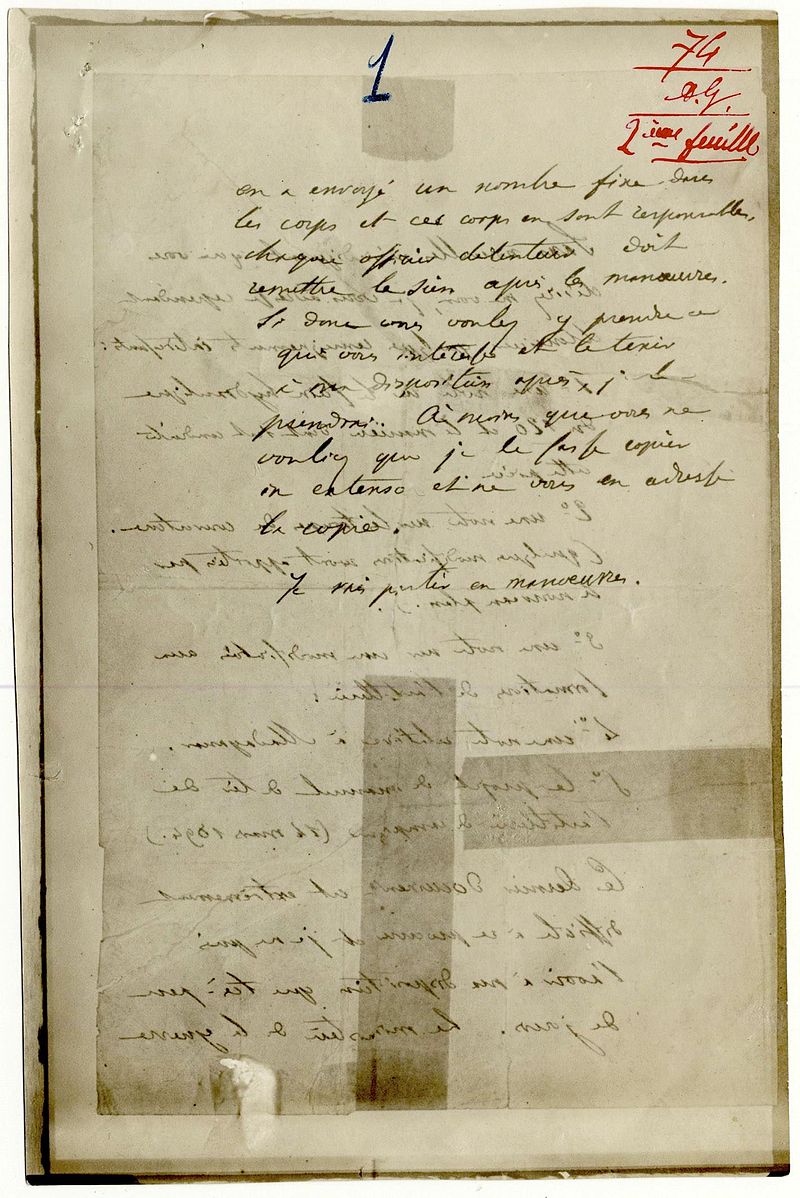

On September 26, 1894, Henry noticed that the writing on six various pieces of torn paper in Bastian’s latest delivery were written in French, rather than the usual German. Henry and a colleague reconstituted the document, which revealed a number of French military secrets. French intelligence had suspected someone in the war ministry had been leaking secrets to the Germans—and now here was a damning document written by the hand of the traitor.

Page of the bordereau, the key piece of evidence used to convict Dreyfus

The document pieced together that September day in Paris, called “the bordereau,” would launch a criminal process that would divide and convulse France for decades. The events set in motion would become known as “the Dreyfus Affair,” after the Jewish artillery captain who would be wrongfully convicted not once, but twice, as the result of misguided assumptions, anti-Semitism, prosecutorial misconduct, and a massive military cover-up. The Dreyfus Affair revealed deep divisions in French society and changed the course of the nation’s history.

The Arrest and Investigation of Captain Dreyfus

Who might be the author of the bordereau? When the director of the bureau, Jean Sandherr, inspected the pieced-together document he instantly assumed that the General Staff had a spy in its midst. The bordereau referenced, among other secrets, a 120 mm cannon, a firing manual for the field artillery, and modifications in artillery formations. To Sandherr, this suggested the spy had to be an artillery officer. Moreover, the range of other topics referenced suggested a broad knowledge of the entire spectrum of the General Staff’s work. In Sandherr’s mind, this pointed to the crop of officer trainees, because their training caused them to rotate from department to department.

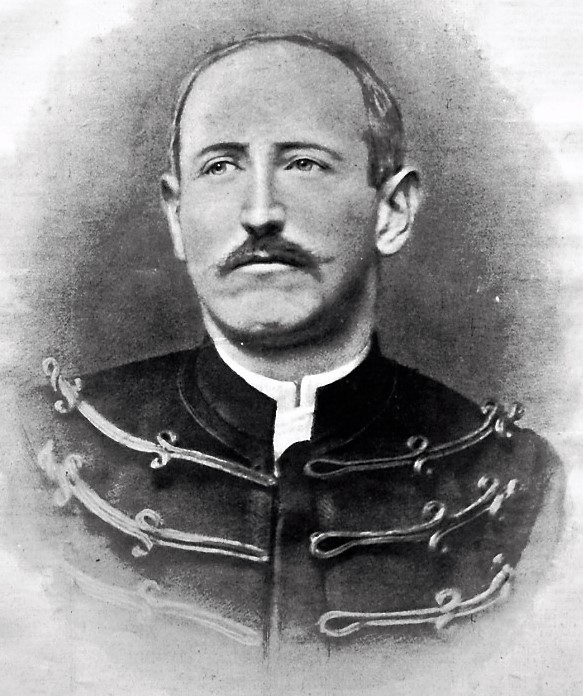

Captain Alfred Dreyfus

When the list of officer trainees was examined, one named jumped out: Alfred Dreyfus. Dreyfus was a thirty-five-year-old artillery officer trainee. Though widely acknowledged to be competent and intelligent, he was unpopular with some of his superiors for the simple reason he was Jewish. And, according to Louis Begley in his book, Why the Dreyfus Affair Matters, “anti-Semitism—of the traditional religious sort, as well as economic and racial—had reached an intensity never before experienced in France.” Frequent complaints were heard about the Jewish “stranglehold” on the French economy or its perverse influence on French intellectual and artistic life. (This despite the fact that Jew’s constituted less than 0.3% of the French population of 39 million.) Director Sandherr’s comments on the case, as reported by Maurice Paleologue of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs after a visit by Sandherr, suggest the degree to which anti-Semitism influenced his thinking about Dreyfus’s guilt. Sandherr pointed to “his indiscreet curiosity, his constant snooping, his air of mystery, and finally his false and conceited character, in which one recognizes all the pride and ignominy of his race. . .”