The Court-Martial of Alfred Dreyfus: An Account of the Dreyfus Affair

by Douglas O. Linder (2020)

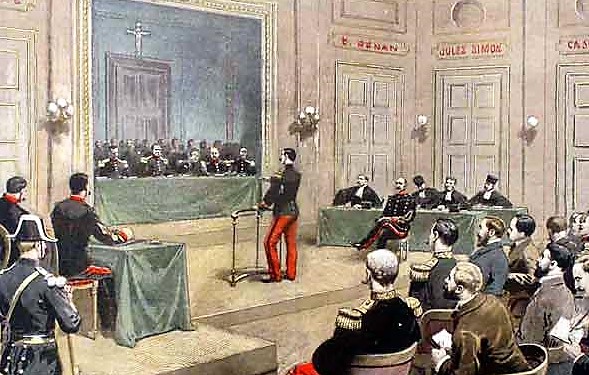

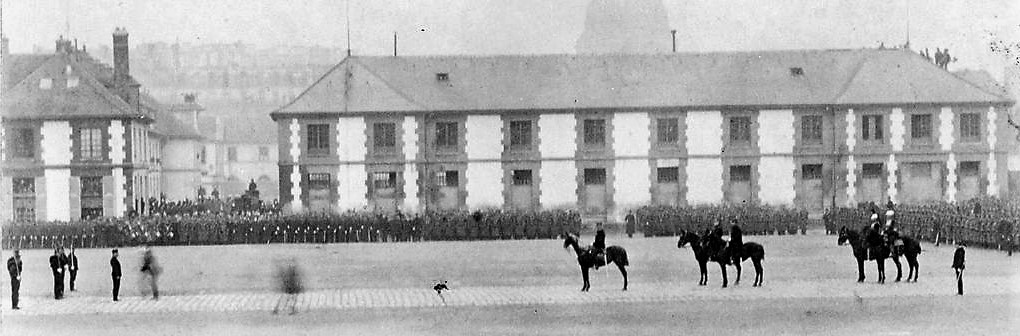

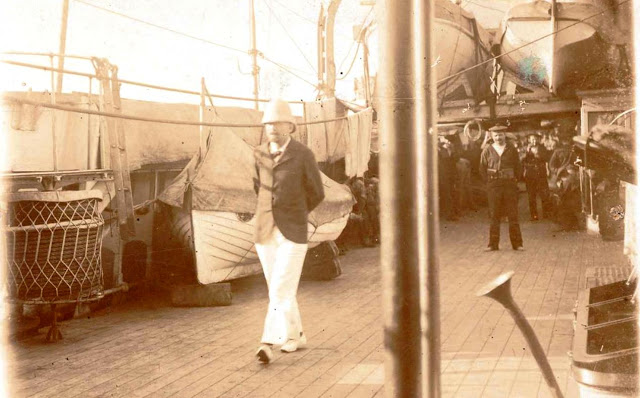

Scene from Dreyfus's 1899 court-martial in Rennes

Madame Marie Bastian became the most important cleaning woman in history by simply doing her job—as an agent of the Statistics Section, the intelligence unit of the French Army’s General Staff. Bastian worked at the German Embassy in Paris, where one of her duties was to empty the wastebasket of the German military attaché, Lieutenant Colonel Maximillian Von Schwartzkoppen, and throw the contents in the furnace. Instead, Bastian delivered whatever she gathered from the wastebasket to Major Hubert-Joseph Henry in the Statistics Section, who would sift through the papers for anything of potential interest to French intelligence.

On September 26, 1894, Henry noticed that the writing on six various pieces of torn paper in Bastian’s latest delivery were written in French, rather than the usual German. Henry and a colleague reconstituted the document, which revealed a number of French military secrets. French intelligence had suspected someone in the war ministry had been leaking secrets to the Germans—and now here was a damning document written by the hand of the traitor.

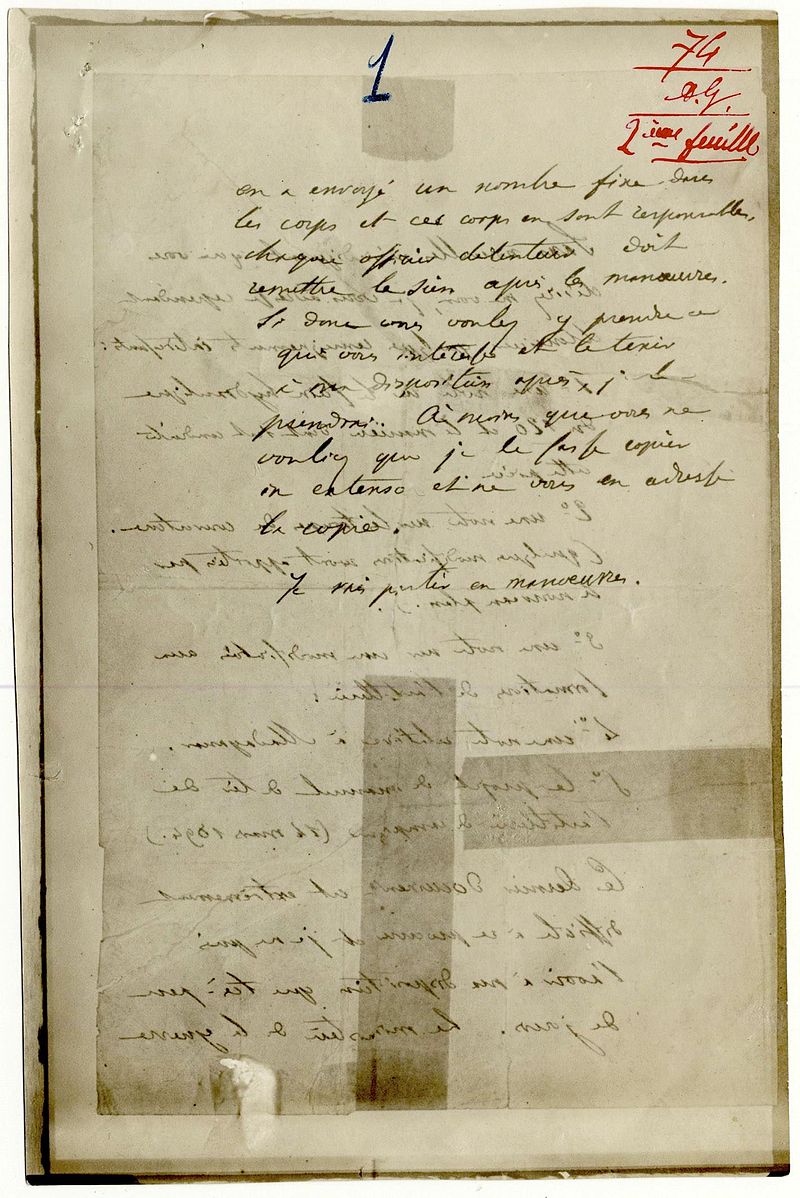

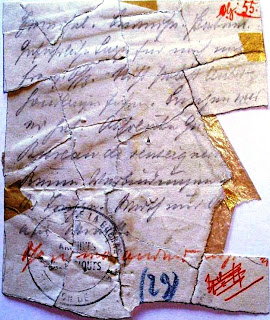

Page of the bordereau, the key piece of evidence used to convict Dreyfus

The document pieced together that September day in Paris, called “the bordereau,” would launch a criminal process that would divide and convulse France for decades. The events set in motion would become known as “the Dreyfus Affair,” after the Jewish artillery captain who would be wrongfully convicted not once, but twice, as the result of misguided assumptions, anti-Semitism, prosecutorial misconduct, and a massive military cover-up. The Dreyfus Affair revealed deep divisions in French society and changed the course of the nation’s history.

The Arrest and Investigation of Captain Dreyfus

Who might be the author of the bordereau? When the director of the bureau, Jean Sandherr, inspected the pieced-together document he instantly assumed that the General Staff had a spy in its midst. The bordereau referenced, among other secrets, a 120 mm cannon, a firing manual for the field artillery, and modifications in artillery formations. To Sandherr, this suggested the spy had to be an artillery officer. Moreover, the range of other topics referenced suggested a broad knowledge of the entire spectrum of the General Staff’s work. In Sandherr’s mind, this pointed to the crop of officer trainees, because their training caused them to rotate from department to department.

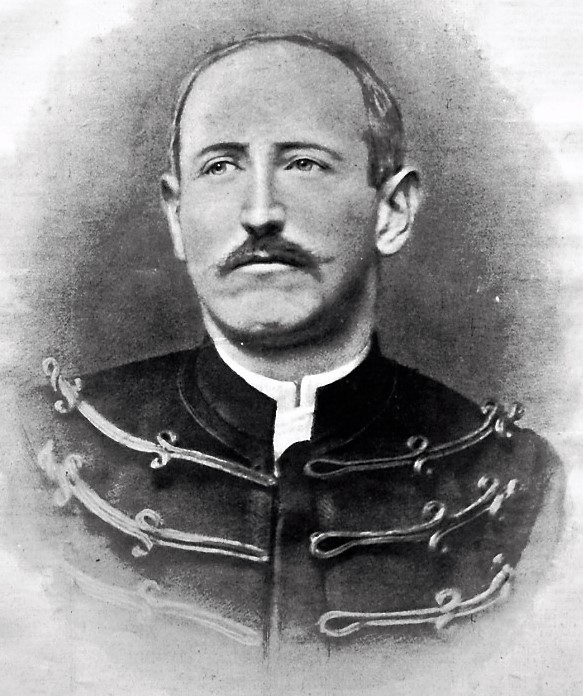

Captain Alfred Dreyfus

When the list of officer trainees was examined, one named jumped out: Alfred Dreyfus. Dreyfus was a thirty-five-year-old artillery officer trainee. Though widely acknowledged to be competent and intelligent, he was unpopular with some of his superiors for the simple reason he was Jewish. And, according to Louis Begley in his book, Why the Dreyfus Affair Matters, “anti-Semitism—of the traditional religious sort, as well as economic and racial—had reached an intensity never before experienced in France.” Frequent complaints were heard about the Jewish “stranglehold” on the French economy or its perverse influence on French intellectual and artistic life. (This despite the fact that Jew’s constituted less than 0.3% of the French population of 39 million.) Director Sandherr’s comments on the case, as reported by Maurice Paleologue of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs after a visit by Sandherr, suggest the degree to which anti-Semitism influenced his thinking about Dreyfus’s guilt. Sandherr pointed to “his indiscreet curiosity, his constant snooping, his air of mystery, and finally his false and conceited character, in which one recognizes all the pride and ignominy of his race.”

Jean Sandherr, Director of the Statistics Section of the War Ministry

Dreyfus, objectively, was an unlikely candidate as the spy. He was happily married with two young children. He had no debts or significant vices. He was a graduate of France’s two most elite institutions, including the equivalent of the U.S. Army War College. He had earned his spot on the General Staff under a program that guaranteed positions to war college graduates finishing among the top twelve in their class. (Dreyfus finished ninth in the class. He would have finished third, but for the fact that one of the generals who would later be a member of Dreyfus’s jury, who had Dreyfus as a student, gave him a 19/20 score for technical knowledge, but 0/20 for personality. General Pierre de Bonnefond, who gave Dreyfus the “zero” for personality was well-known for his rabid anti-Semitism.) His military record, since beginning service on January 1, 1893, was spotless. Dreyfus seemed to love the military life. He had no known association with either right-wing or left-wing causes, and no significant connection with Germany. Besides all this, Alfred Dreyfus was a rich man, with a wife shoes family had made a bundle in the diamond business. He and his wife, Lucie, had a large apartment and saddle horses—Dreyfus was hardly the most likely recruit to be bought off with a modest pot of German marks.

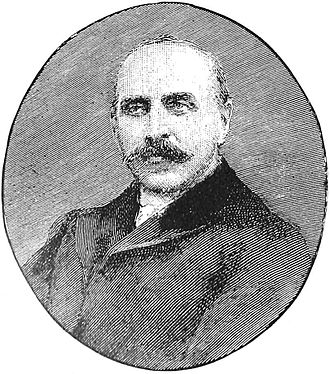

Minister of War Auguste Mercier

But Dreyfus was without any protector in high places—and his life of wealth privilege status might have worked against him. Top staff thought they had their man and ordered a sample of Dreyfus’s handwriting. Confirmation bias (the strong tendency to believe what supports are existing beliefs), as well as the fact that Dreyfus and the real author of the bordereau both were taught the same slanted, very cursive style of writing, led them to believe that Dreyfus was the spy. General Auguste Mercier, the minister of war and a longstanding fan of graphology, compared the bordereau and the sample of Dreyfus’s writing over the weekend and reached the same conclusion. Dreyfus was their traitor.

On Saturday October 13, Dreyfus received a note ordering him to report to the Ministry of War the next Monday morning. He considered the matter to be unimportant. Taken to a room where three men, including Commandant Armand du Paty de Clam and the chief of the secret police and his secretary, Dreyfus received a strange request. As Dreyfus describes it in his diary, du Paty asked him, “I have a letter to write, and as my finger is sore, will you write it for me?” Dreyfus proceeded to write the letter as du Paty dictated it. As soon as Dreyfus completed the task, du Paty “arose, placed his hand on my shoulder, and cried out in a loud voice: ‘In the name of the law, I arrest you; you are accused of the crime of high treason.” Dreyfus writes, the infamous accusation was like a “thunderbolt falling at my feet.” Dreyfus was searched and taken to a nearby military prison, where he was placed in solitary confinement and denied all forms of communication. Dreyfus, crazed with grief, walked back and forth in his narrow cell knocking his head against the wall.

Over the course of the next two weeks, Dreyfus, while still ignorant of the pieced-together document that was the basis of the charge against him, was interviewed several times by du Paty. According to Dreyfus, the relentless questioning almost caused his “brain to fail” and left him “struggling in a void.” Only after fifteen days was he shown a photograph of the bordereau.

The official preliminary investigation began soon thereafter. The seven-week investigation turned up nothing in Dreyfus’s private life that could provide a motive for his alleged spying. Nonetheless, on the basis of the conclusion by two handwriting experts that Dreyfus was the author of the bordereau, Judge Advocate Brisset moved for an indictment. Alphonse Bertillon of the Judicial Police, conceded there were marked dissimilarities between Dreyfus’s writing samples and the bordereau, but suggested that they were the result of “self-forgery,” and that Dreyfus altered his usual handwriting in various ways on the bordereau. (One of the two experts who identified Dreyfus as the author would admit his error five years later. Two other experts consulted in the investigation, including one from the Bank of France, had concluded that Dreyfus’s handwriting did not match that of the bordereau.)

The 1894 Court-Martial

The decision whether to prosecute belonged to Minister of War Mercier. Against the advice of his highest ranking army officer, who suggested it would be easier to send Dreyfus to Africa in the hopes that he might be killed in the ongoing fighting there, Mercier decided to go forward with a prosecution. Mercier did agree, however, at the urging of Premier Charles Dupuy and others concerned with the flimsiness of the evidence against Dreyfus and the utter lack of any motive for his crime, to drop the prosecution if no additional proof of guilt could be found.

For those committed to seeing Dreyfus punished, the lack of evidence against him produced on need on their part to create it. Major Henry, a man of few scruples, was up to the task. With the assistance of an archivist, Henry assembled what became known as “the secret dossier.” The collection of documents included forged, altered, and embellished letters, exchanged between Schwartzkoppen and other foreign military officers. Together, they suggested Dreyfus was up to no good. The most damning of the letters was one from the Italian military attaché Alesandro Panizsardi to Schwartzkoppen about French plans for a new military installation at Nice that “cette canaille D. [that swine D] has given me for you.” Accusers would insist, of course, that “D.” was Dreyfus, but it later was shown that the actual supplier of the information was Jacques Dubois, a civilian who worked in the War Ministry’s Cartography Section.

Dreyfus's defense lawyer Edgar Demange (L), and Fernand Labori (R)

The Dreyfus court-martial opened on December 19, 1894. The prosecution moved almost immediately to close the sessions to the public. Dreyfus’s defense attorney, Edgar Demange, objected strenuously to the move. Well aware of the bias against his client within the War Ministry, Demange’s trial strategy largely depended on making the public aware of the preposterously weak evidence of his client’s guilt. The presiding judge ordered the proceedings closed, most likely sealing Dreyfus’s fate.

Two days of witness testimony added little to the prosecution case beyond that offered by their handwriting experts. Witnesses testified that Dreyfus had associated with women of allegedly loose morals and had gambled on occasion. They told the court that Dreyfus has an unpleasant personality and was too curious for his own good. Hardly the stuff that proofs guilt, or even supplies significant evidence of a possible motive.

The only new evidence, damning if true, came from Major Henry, who testified that as early as last February he had been warned by an honorable person that a traitor was lurking in the Ministry of War. Moreover, the person said, the traitor was assigned to the Second Department of the General Staff, Dreyfus’s specific posting. Henry dramatically pointed his finger at Dreyfus and shouted, “Le traitre, le voici! [The traitor! Here he is!] The testimony and accompanying theatrics caused Demange to leap to his feet and demand the name of Henry’s alleged informant. Henry replied, pointing to his officer’s cap on his head, “There are things in an officer’s head that even his kepi [cap] isn’t allowed to know!”

Even with Henry’s testimony, the case against Dreyfus seemed very weak. Top French officials thought an acquittal seemed likely. Dreyfus described himself as highly confident that he would be cleared. Fully aware of the potential for an acquittal General Mercier played his trump card. He gave the secret dossier to du Paty and sent him to the hearing. His instructions were to deliver the dossier to the president of the tribunal in secret. Dreyfus and his counsel were to be given no opportunity to challenge the dossier’s contents or even learn of its existence. Despite being a clear violation the military code, the plan worked as intended. The dossier convinced the wavering military judges of Dreyfus’s guilt.

In the hour or so of deliberations, the judges read aloud and debated the meaning of the contents of the secret dossier. Then they voted unanimously to convict Dreyfus. He was ordered to suffer a military degradation and imprisonment for life in a fortified enclosure. It was the most severe punishment allowed under French law.

The Degradation, Appeals, and Five Years on Devil’s Island

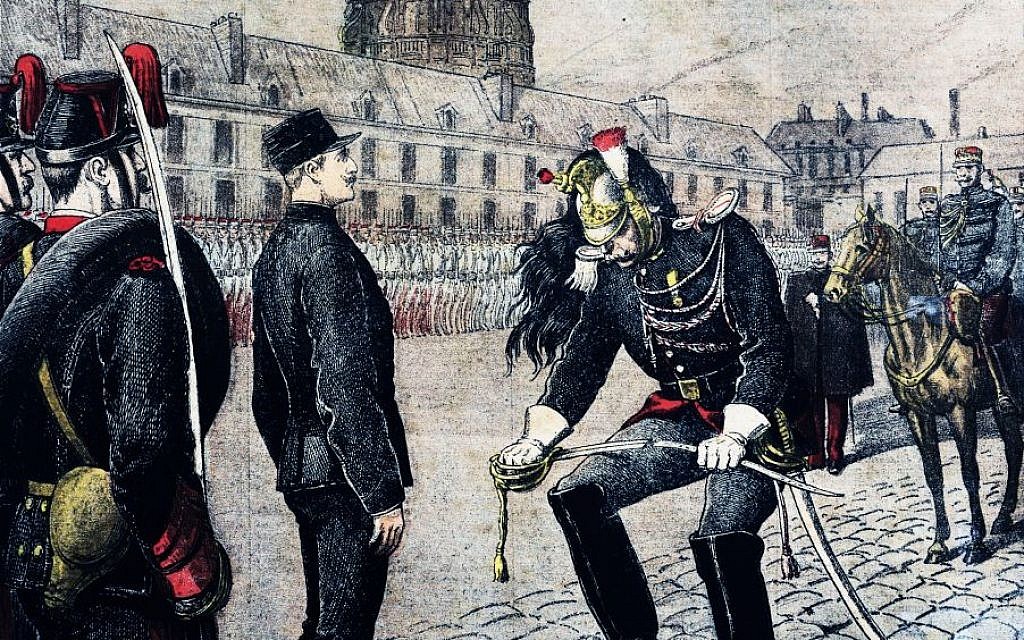

Photo of Dreyfus's Degradation at the Ecole Militaire (Dreyfus is the fourth figure from the left in the foreground).

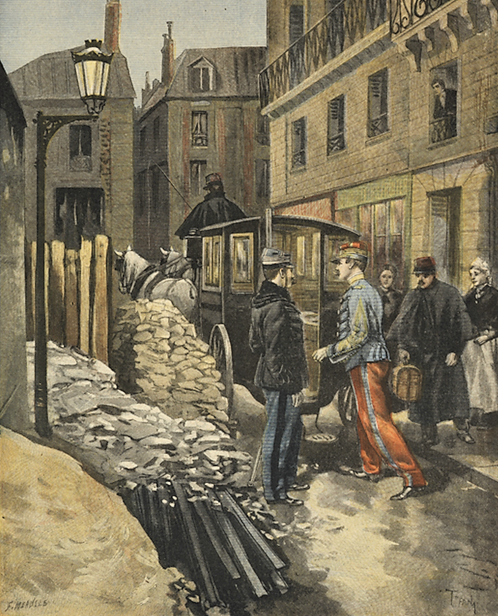

At nine o’clock on January 5, 1895, the bells of the clock at the Ecole Militaire sound in the courtyard and General Darras lifted his sword and shouted, “Portez armies!” All eyes turn to a corner of the square where Alfred Dreyfus, between four artillerymen, marches toward the General. The group halts, trumpets blow, drums beat, and then silence.

The General announces, “Captain Dreyfus, you are unworthy to wear a uniform. In the name of the French people, we deprive you of your rank.” Dreyfus lifts his hands to the air and says loudly, “I am innocent. I swear I am innocent! Vive la France!” From the soldiers comes the clamor, “Death to the traitor!” The crowd hushes as the adjutant begins tearing stripes from Dreyfus’s hat, ripping the embroideries off his cuffs, and numbers from his collar. He grabs the sabre from Dreyfus’s scabbard and breaks it across his knee. The two portions of the sabre are thrown to the ground. Dreyfus has been officially degraded. He again raises his voice and says, “You are degrading an innocent man!” To the cries “Traitor!” and “”Judas!” and “Dirty Jew!”, Dreyfus is marched by his former comrades and led to a waiting prison van.

Dreyfus watches as his sabre is broken during his degradation ritual.

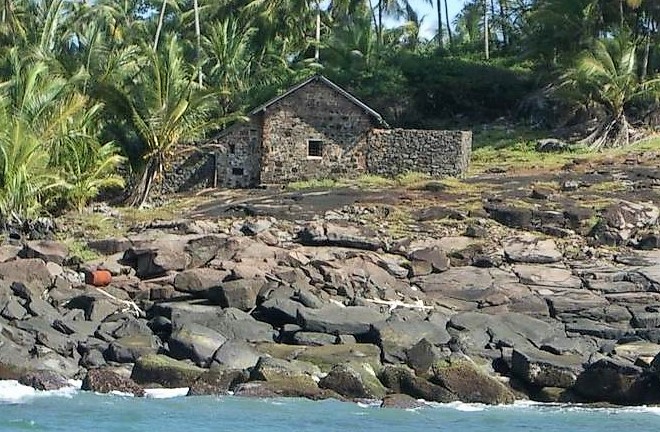

The humiliating degradation ceremony was a dramatic prelude to what would become five years of tedium, suffering, and mental challenges in the most godforsaken, malaria-infested corner of the world French authorities could offer: Devil’s Island. Located six miles off the coast of French Guiana, Devil’s Island, at less than one square mile, was the smallest of three Salvation Islands. Before becoming a prison, the arid and rocky island had been home to a leper colony.

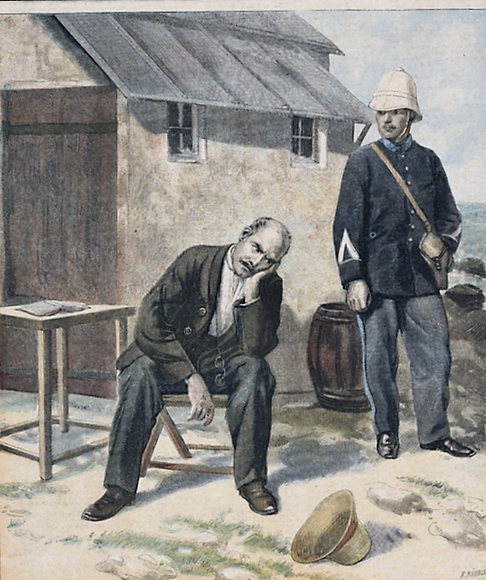

After fifteen days at sea, the Saint-Nazaire anchored on March 12, 1895 in the Salvation Islands. Dreyfus was taken to a small stone hut. Its two windows were grated. In an ante-room a guard was always on duty, replaced by another every two hours. Dreyfus was allowed, during the day, to walk—accompanied by an armed guard—in a treeless space of about one-half acre. Daytime temperatures often exceeded 100 degrees, but Dreyfus had no means of taking a shower. He was subject to frequent random body searches and deprived of all news from the outside world. He was told not to speak to anyone.

Dreyfus on Devil's Island

Beginning in April, on the first day he was able to obtain paper, Dreyfus kept a diary (which was later published and dedicated to his children). It opens with the line: “Today I begin the diary of my sad and tragic life.” In his first entry, Dreyfus revealed that he first intended to kill himself rather than carry on what seemed like a hopeless mission of obtaining justice. He said that he had lost his faith in human justice and was “broken in body and spirit.” He called his degradation “a punishment worse than death” and that every hope he held has met “with a new deception.”

Dreyfus’s health deteriorated. He suffered from malaria, dysentery, insomnia, a fever diagnosed as “cerebral congestion,” and infected insect bites. For a two-month period (following a false rumor about his escape that led to calls for even stricter confinement), Dreyfus was shackled at night to his metal bed by two iron buckles around his ankles. Unable to move, he spent nights enduring biting ants, mosquitoes, and swarms of spider crabs. Devil’s Island was indeed as close to hell as one could get.

But he valiantly fought to retain his sanity. He translated Shakespeare into French, learned English, and reconstructed from memory essential elements of integral and differential calculus.

Dreyfus's prison hut on Devil's Island

The last entry in the Devil’s Island diary is dated September 10, 1896. It begins: “I am so utterly weary, broken down in body and soul, that today I stop my diary, not being able to foresee how long my strength will hold out, or what day my brain will succumb under the weight of so great a burden.” He ends the diary with a plea to the President of the Republic, declaring “once more that I am innocent of this abominable crime” and asking for only “one thing”—“that the search for the culprit who is the real author of this base crime be diligently prosecuted.”

Dreyfus would remain on Devil’s Island for another three years. He barely survived. A government report noted that he had difficulty completing sentences. A September 1899 report called him “a finished man.”

The Dreyfusards and the anti-Dreyfusyards: Innocence Debated

By 1898, the Dreyfus Affair was threatening to tear France apart. On the one side, in the pro-Dreyfus camp, were centrist and left-wing politicians, as well most intellectuals, writers, artists, and academics. Some members of the clergy also threw themselves in with the Dreyfusards. Outside of France, diverse figures including Queen Victoria, the explorer Henry Stanley, and Mark Twain all had spoken out in opposition to the Dreyfus verdict. In addition to the troubling lack of a motive, Dreyfusards pointed to trial irregularities that had been revealed in the years since the court-martial.

On the other side, in the anti-Dreyfus camp, were a coalition of army officers, nationalists, anti-republicans, royalists, members of the conservative bourgeoisie, and anti-Semites. Some took their position out of bigotry, some out of blind trust of the military and its process, and some out of a belief that the honor of the military was far more important than the issue of Dreyfus’s guilt or innocence.

One of the most important defenders of Dreyfus was his brother, Mathieu, who left military service to throw himself virtually full-time into the cause of clearing Alfred’s name. An early ally of Mathieu was Ferdinand Forzinetti, the commander of the military prison where Dreyfus was held between his arrest and his conviction and removal to Devil’s Island. Forzinetti was convinced that the behavior of Alfred that he observed at the prison was wholly inconsistent with that of a guilty man. He gave Mathieu a copy of the prosecution’s act of indictment which would be key to efforts to exonerate Dreyfus.

Another person whose support proved critical was Dr. Gibert, a physician troubled by the lack of motive and Dreyfus’s insistence on his own innocence, was connected enough to have actually raised the Dreyfus conviction in a conversation he had with the Felix Faure, president of the republic. Gibert reported to Mathieu that the president had told him that his brother was not convicted based on the bordereau, as almost everyone but the military insiders supposed, but rather on the basis of a highly incriminating secret dossier that not even Dreyfus’s defense attorney was aware of. Mathieu immediately understood that this information could be the basis for a challenge to Alfred’s conviction.

Following first rumors and then more solid leads, Dreyfus’s defense lawyer Demange established the existence of a letter from one foreign attache to another that made reference to “that swine D.”, a spy that might have been the key basis for his client’s conviction. On September 18, 1896, Lucie Dreyfus, Alfred’s wife, sent a letter to the Chamber of Deputies urging that Alfred’s conviction be overturned on the ground that the judges’ reliance on the secret dossier was “a denial of justice.” Less than two months later, after the bordereau found its way into print in a right-wing newspaper, Mathieu was able to retain numerous handwriting experts willing to assert with confidence that the author of the bordereau was not Alfred. Still, despite these defense efforts, it came as no surprise when the Chamber of Deputies refused to act on Lucie’s petition.

Major Georges Picquart

No man deserves more credit for turning around Dreyfus’s fortunes than Major Georges Picquart, the very same officer who greeted Dreyfus when he arrived at the Ministry of War on the day of his arrest and who, through the court-martial process, felt certain Dreyfus was the spy. In his book Why the Dreyfus Affair Matters, Louis Begley describes Picquart as the “model officer, incarnating all the traditions of the army and the General Staff” who became Dreyfus’s “champion and savior,” not out of any personal ambition (in fact, his efforts were career-threatening in the extreme), but simply because he believed in justice and doing right.

Picquart took on his role of championing Dreyfus’s cause after he became convinced he had found the real spy, and he was not named Alfred. The evidence that would ultimately save Dreyfus was a letter written by the same German officer, Schwartzkoppen, who was the recipient of the bordereau. The March 1896 letter, referred to in the Dreyfus Affair as “the petit bleu” because it was written on a special blue paper that was whizzed through Paris pneumatically on a series of pipes, expressed unhappiness with his French spy and ended with the note that without some additional information from the spy he might have to discontinue “my relations with the house of R.” The envelope was addressed to Esterhazy, and included his home address and rank. The letter, found in the wastebasket at the German embassy by the dutiful Madame Bastian, had been torn into pieces, and apparent draft that Schwartzkoppen decided to discard.

"The petit bleu"

The letter was assembled at the Statistics Section, where Picquart was now the new man in charge. Picquart launched an informal investigation of Ferdinand Esterhazy. He established that Esterhazy had been asking many questions of fellow officers and, more importantly, that Esterhazy’s handwriting seemed a clear match with that found on the bordereau. Picquart then examined the secret dossier and determined, in light of the new evidence, that it had little or no probative value. He then wrote a report urging a formal investigation of Esterhazy.

You might expect, based on Picquart’s filing of a report, that the massive injustice suffered by Dreyfus would soon be corrected. But you’d be wrong. From the standpoint of Picquart’s superiors, what mattered most was the honor of the army. Dreyfus was a pawn who must be sacrificed in the political chess game. General Arthur Gonse, upset with Picquart’s continuing insistence that the Dreyfus case be reopened, put the matter bluntly: “What do you care if that Jew rots on Devil’s Island?”

General Arthur Gonse

Picquart was not easily dissuaded from his efforts by the argument that the reputation of the army would suffer. He told Gonse, “What you are saying, General, is abominable. I will not in any event take this secret with me to the grave.” With that remark, Picquart’s military fate was sealed.

Picquart’s willingness to put principle over the over military discipline rankled senior officers. The generals also worried that Picquart knew too much. Doctoring documents not only constituted a gross violation of Dreyfus’s right to due process; it was a crime under French law. The solution to the Picquart problem they settled on was to send him off on faraway missions. Picquat was ordered first to northeast France, then to the Alps, then to Tunisia and Algeria. Sometime during these diverse intelligence missions, Picquart drafted a letter including everything he knew about the Dreyfus Affair cover-up and gave it to his lawyer, with instructions that it be delivered to the president of the republic in the event of his death.

And what to do to ensure Dreyfus never was vindicated? Henry went back to his old tricks, fabricating a new piece of unrebuttable evidence against Dreyfus—a piece of evidence that came to be called la massue (the club). (Two years later, after his latest forgery was discovered, had this to say: “I saw my chiefs were worried. I wanted to calm them; I wanted to put minds at ease.”) The text of the club, allegedly a letter between an Italian official and Schwartzkoppen, suggested Dreyfus was also feeding French military secrets to the Italians.

Major Hubert-Joseph Henry

Henry’s forgery was crude. More damningly, on close inspection the lines on the two papers he put together (one using text from a genuine letter sent by an Italian military attache and one adding text of his own creation) were different shades of blue and gray. Once the forgery was uncovered it took on a new name. No longer the club, it became the faux Henry (the Henry forgery).

Henry’s deviousness did not stop there. (Henry was very much an Iago-like character.) Henry sought about trying to convince his superiors that Picquart was leaking secrets to “the Jewish Syndicate” and needed to be arrested. In November 1897, he went a step further and forged two cables to Picquart, allegedly from foreigners using the names “Speranza” and “Blanche,” intended to incriminate Picquart. One cable warned Picquart “everything has been revealed,” while the other suggested there was proof that Picquart had authored the “petit bleu” in an attempt to frame Esterhazy and, thereby, help exonerate Dreyfus. Henry also addressed an anonymous letter to Picquart advising him to flee, and then showed the allegedly intercepted letter to a superior, General Billot. (Are you readers following all this? It’s complicated!) The letter finally convinced Billot to appoint Henry to investigate Picquart.

Commandant Ferdinand Esterhazy, the real traitor

All this might have worked—except for a securities trader named J. de Castro. Castro had professional dealings with Esterhazy for many years. When he saw a published copy of the bordereau, he immediately identified the handwriting of that of his client. Castro discussed his discovery with friends, who eventually put him in touch with Mathieu Dreyfus. On November 15, 1897, Mathieu denounced Esterhazy to General Billot as the real traitor.

The High Command knew it was facing a crisis. They might have to free Alfred Dreyfus, or at least provide a new trial. But they worried about their own criminal liability and careers—and about the honor of the army as a whole. One lie had led to another, and now, it seemed, they might be trapped. Perhaps doing nothing was the best approach. Perhaps the problem will fade away? Predictably, about the only thing the generals could agree upon was the need to punish the whistleblower, Picquart. Esterhay, meanwhile, was court-martialed, but acquitted—a move seen by some as an attempt to head off a reopening of the Dreyfus case based on a claim of Esterhazy’s alleged authorship of the bordereau. General Billot, after all that had been revealed and all that he knew, still declared, “The Dreyfus case has been regularly and justly decided.”

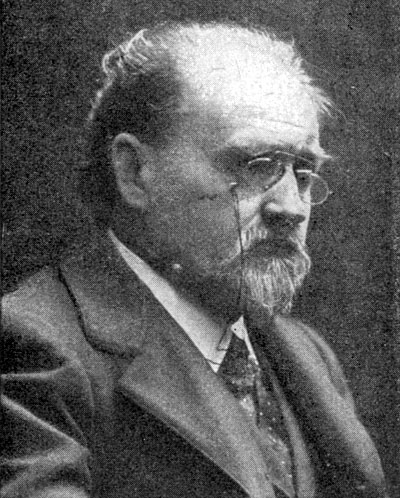

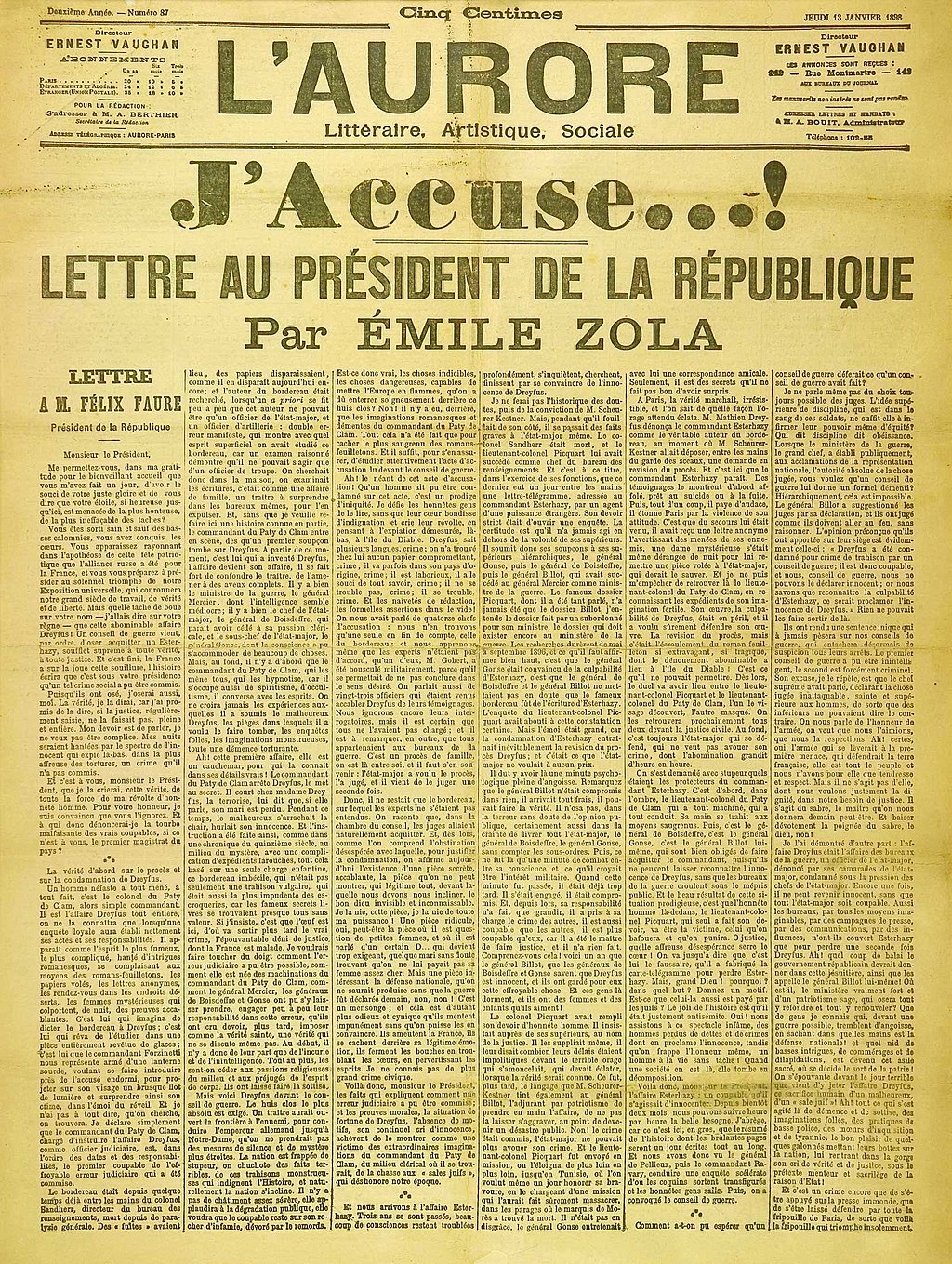

Novelist and ardent support of Dreyfus, Emile Zola

Whatever hopes the High Command might have had that the public would lose interest in the Dreyfus Affair were dashed by France’s best-known novelist of the time, Emile Zola, who became a fearless crusader for Dreyfus’s cause. Zola realized early on that the fight to free Dreyfus could not be won it the courts alone; it first had to be won in the court of public opinion. He wanted to deliver, he said, “a hard punch.” He did that by publishing multiple pieces in the popular publication Le Figaro. On January 13, 1898, Zola followed up by publishing an open letter to President Felix Faure with the title “J’accuse!” (I Accuse). “J’accuse!” was a masterpiece of political literature, laying out in compelling fashion the case for Dreyfus’s innocence: the reliance on a single piece of evidence, the myth about secret incriminating evidence that dare not be revealed, the complete lack of any evidence of motive, Dreyfus’s sterling record, and, finally, the strong evidence that Esterhazy was the real author of the bordereau. Zola also suggested that top military officials were engaging in a cover-up and that the military was afraid of the consequences of admitting its mistake in the Dreyfus court-martial.

Zola understood that is speaking out put him at risk of prosecution for criminal libel. He said he was ready for it: “Let them dare bring me before the assizes, and let the inquiry take place in the light of day! I am waiting!” (A criminal libel complaint on behalf of the military judges of the Esterhazy court-martial was filed against Zola. The prosecution made the libel case a choice between siding with Zola and the Dreyfusards or supporting the army. Zola was convicted and sentenced to a year in prison, but the Court of Cassation overturned the conviction on the ground that General Billot, who filed the suit, lacked standing to sue on behalf of the judges. Zola was retried, again found guilty, and fled to England to avoid imprisonment.)

Under French law, Dreyfus’s only hope for reversal of his conviction was review by the Court of Cassation, and only the government itself could request review in that court. The wheels of justice finally began turning in Dreyfus’s favor after national elections in 1898, when a new government headed by Henri Brisson, more receptive to the notion of review, took power in late June.

But Brisson’s Minister of War, Godefroy Cavaignac, was a determined opponent of judicial review. Cavaignac ordered a review of the evidence used to convict Dreyfus, including the secret dossier, as well as confession Dreyfus supposedly made on the eve of his degradation. The Minister fully expected the review to find provid support for Dreyfus’s conviction. Indeed, he thought it did just that. He delivered a major speech in which he read the full text of the faux Henry, as well as the text of letters from the secret dossier. When Picquart answered with a letter to the prime minister calling those documents forgeries, Cavaignac ordered his arrest.

The arrest of Georges Picquart

Brisson would later say his Minister of War was “hypnotized” by his hatred of Dreyfus. But after Henry confessed on August 30 to his forgery, then slit his throat with a razor the next day, even Cavaignac came around. Dreyfus would finally get judicial review of his conviction. The government filed a petition in the Court of Cassation on September 16, 1898, asking for just that. On June 3, 1899, the Court overturned Dreyfus’s conviction and ordered a re-trial.

A Second Court-Martial and Finally Exoneration

Ten days after the reversal of his conviction, Alfred Dreyfus started his voyage from Devil’s Island back to France on a naval cruiser. He was provided with a new suit and hat for the occasion. The same day, all criminal charges against Georges Picquart were dismissed.

Photograph of Alfred Dreyfus in 1899

Dreyfus’s second court-martial opened in Rennes beginning on August 7, 1899. Tensions ran high and police presence was high. Even so, one of the members of the defense team was shot and wounded by an assailant. As the indictment was read, Dreyfus’s eyes filled and tears ran down his cheek.

A month later, the military judges rendered their decision. By a vote of 5 to 2, they found Dreyfus guilty, but with extenuating circumstances. The sentence imposed was ten years imprisonment. Dreyfus heard the sentence read without the least show of emotion.

Photo of court martial in Rennes (2899)

With the now ample evidence of Dreyfus’s innocence, what explanation was there for the tribunal’s verdict? Perhaps the best answer was provided by Britain’s Lord Chief Justice, Lord Russell, in his report to Queen Victoria on the court-martial: “The explanation of the erroneous judgment. . . I take to be this: they were unversed in the law, unused to legal proceedings, with no experience or aptitude to enable them to weigh the probative effect of testimony; they were steeped in prejudice and concerned for what they regarded as the honor of the army and thus, impressed or overawed by the heads of their profession, they gave weight to the flimsy rags of evidence which alone were presented against the accused man.” Russell also noted that Dreyfus was a terrible witness, “mean-looking” with “a hard, unsympathetic face.” Moreover, his testimony, in a dry, monotone voice, lacked “frankness” and “nobility in his expression.”

Dreyfus, in his memoir, called the verdict against the “plainest evidence” and “all justice and equity.” He did, however, commend the two judges who “rose above the party spirit” and clove “to the higher ideal . . . of man’s inalienable right to justice.”

The Rennes verdict was not well-received outside of France. Anti-French rallies took place in New York, Milan, Naples, and London. French embassies around the globe needed police to protect them from mob violence.

An appeal would take time and, at best, result in a remand and yet another court-martial that could well produce the same result. So after filing his appeal, Dreyfus was persuaded to withdraw it and seek a presidential pardon. Dreyfus issued a statement accompanying his withdraw of his appeal in which he said, “My heart will know no rest until not one Frenchman is left who holds me responsible for a crime that was committed by someone else.”

The pardon was signed by President Emile Loubet on September 19, 1899. Loubet, to avoid embarrassing the army, framed the pardon as a humanitarian gesture justified by Dreyfus’s poor health. The army issued a statement saying that while it supported the decision of its military judges, it “bowed to the sentiment of profound pity that has guided the president of the republic.” Army officials pushed for, and won, enactment of a law that covered all crimes committed in connection with the Dreyfus Affair.

Emile Zola died in 1902, the victim of carbon monoxide poisoning caused by a blocked stove in his bedroom. Foul play cannot be ruled out. Dreyfus attended Zola’s burial at a Paris cemetery. A riot at the cemetery, stoked by the anti-Semitic press, had to be broken up by mounted police. (Six years later, when Zola’s remains were transferred to the Pantheon, Dreyfus was injured at the ceremony when the bullet fired by a would-be assassin pierced his arm.)

In the years following the pardon, political forces in France shifted in a republican direction. And there were new revelations about the extent of the military cover-up, as well as a confession by Schwartzkoppen that Esterhazy, not Dreyfus, was indeed his French Army source of intelligence.

In 1906, the Court of Cassation unanimously reversed Dreyfus’s conviction. It also voted not to remand the case for a new court-martial. Dreyfus was declared innocent and the incident was closed. By then, most of the public energy on the Dreyfus Affair had been spent, and the decision was greeted with relative calm.

Dreyfus was given the rank of major and inducted into the Legion of Honor. But he was by now age 47, and many of his superiors were younger men. Dreyfus retired from the army the next year, but returned to active service with the outbreak of World War I.

Picquart was made a brigadier general, and then promoted to minister of war. When Dreyfus congratulated Picquart on his new position, Georges said he owed his post to Dreyfus. Dreyfus responded, “No, it was because you have done your duty.”

Years later in his masterpiece, Remembrance of Things Past, Marcel Proust noted how the controversy that so convulsed France for a decade gave way to other concerns including the international tensions that would soon lead the world into war: “Dreyfus was rehabilitated, Picquart became minister of war, and nobody said boo.”

Dreyfus died at his home on July 12, 1935. His wife Lucie died ten years later.