Alfred Dreyfus in His Own Words:

Chapter 3 "The First Court Martial of 1894"

(Source: Five Years of My Life: The Diary of Captain Alfred Dreyfus)

WHEN MY EXAMINATION by Commandant du Paty had been closed, the order was given by General Mercier, Minister of War, to open a "regular instruction" (a general investigation, chiefly conducted by the secret military police, of my past life). My conduct, however, was beyond reproach: there was nothing in my life, actions, or relations on which to base any ignoble suspicion.

On the 3rd of November General Saussier, Military Governor of Paris, signed the order for an official preliminary investigation of the case for the Court.

This preliminary investigation was entrusted to Commandant d'Ormescheville, rapporteur, or Examining Judge, of the First Court Martial of Paris. He was unable to bring an exact charge. His report was a tissue of allusions and lying insinuations. Justice was done to it even by the members of the Court Martial of 1894; for at the last session the Commissaire du Gouvernement (Judge Advocate) wound up his speech for the prosecution by acknowledging that there remained no charge of any kind, everything had disappeared, except the bordereau. The Prefecture of Police, having made investigations concerning my private life, handed in an official report that was favorable in every respect; the detective, Guenee, who was attached to the Information Service of the Minis try of War, produced, on the other side, an anonymous report made up exclusively of calumnious stories. Only his last report was produced at the trial of 1894; the official report of the Prefecture of Police, which had been entrusted to Henry, had disappeared. The magistrates of the Supreme Court found the minutes of it in the records of the Prefecture and made the truth known in 1899.

After seven weeks of the investigation, during which I remained, as before, in the strictest solitary confinement, the Judge Advocate, Commandant Brisset, moved, on the 3rd of December, 1894, for an indictment, "the presumption being sufficiently established." These presumptions were based on the contradictory re ports of the handwriting experts, two of whom - M. Gobert, expert of the Bank of France, and M. Pelletier - pronounced in my favor. The other two, MM. Teyssonnieres and Charavay, decided against me while admitting the numerous points of dissimilarity between the handwriting of the bordereau and my own. M. Bertillon, who was not an expert, pronounced against me on the ground of pretended scientific reasons. Everyone knows that, at the trial at Rennes in 1899, M. Charavay publicly and with solemnity acknowledged his error.

On the 4th of December, 1894, General Saussier, Military Governor of Paris, signed the order for the trial.

I was then in communication with Maitre Demange, whose admirable devotion remained unchanged to the end.

All that time they refused me the right of seeing my wife. On the 5th of December I at last received permission to write her an open letter:-

"TUESDAY, DECEMBER 5, 1894.

"My DEAR LUCIE, -

"At last I can send you word. I have just been told that my trial is set for the 19th of this month. I am denied the right to see you. I will not tell you all that I have suffered; there are not in the world words strong enough to give expression to it. Do you remember when I used to tell you how happy we were? Everything in life smiled on us. Then of a sudden came a thunderbolt which left my brain reeling. To be accused of the most monstrous crime that a soldier can commit! Even to-day I feel that I must be the victim of some frightful nightmare....

"But I trust in God's justice. In the end truth must prevail. My conscience does not reproach me. I have always done my duty; never have I turned from it. Crushed down in this sombre cell, alone with my reeling brain, I have had moments when I have been beside my self; but even then my conscience was on guard. 'Hold up thy head!' it said to me. 'Look the world in the face! Strong in thy consciousness of right, rise up, go straight on! This trial is frightfully bitter, but it must be endured!' "I embrace you a thousand times, as I love you, as I adore you, my darling Lucie.

"A thousand kisses to the children. I dare not say more about them to you; the tears come into my eyes when I think of them.

ALFRED."

The day before the trial opened I wrote her the following letter, which expresses the entire confidence I had in the loyalty and conscientiousness of the judges:-

"I am come at last to the end of my sufferings. Tomorrow I shall appear before my judges, my head high, my soul tranquil. I am ready to appear before soldiers as a soldier who has nothing with which to reproach himself. They will see in my face, they will read in my soul, they will know that I am innocent, as all will know who know me. The trial I have undergone, terrible as it has been, has purified my soul. I shall return to you better than I was before. I want to consecrate to you, to my children, to our dear families, all that remains of life to me. Devoted to my country, to which I have consecrated all my strength, all my intellect, I have nothing to fear. Sleep quietly then, my darling, and do not give way to any apprehension. Think only of our joy when we are once more in each other's arms.

ALFRED."

On the 19th of December, 1894, began the trial which, in spite of the strong protests of my lawyer, took place behind closed doors. I ardently desired that sittings should be public, in order that my innocence might shine forth in the full light of day.

When I was brought into the court-room accompanied by a Lieutenant of the Republican Guard, I saw hardly anything and understood nothing. Unmindful of all that was passing around me, my mind was completely taken up with the frightful nightmare which had been weighing on me for so many long weeks, - with that monstrous accusation of treason, the inane emptiness of which I was to prove.

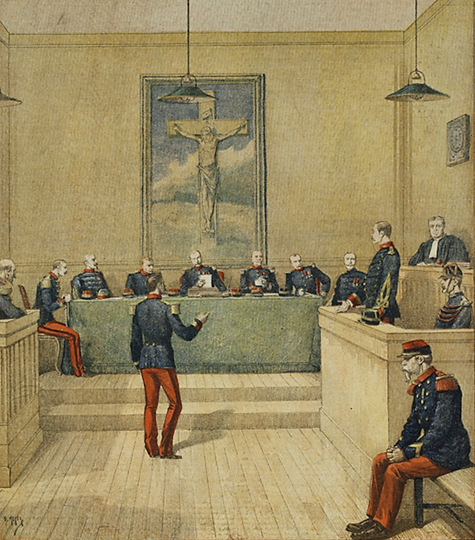

My only conscious impression was that on the platform at the end of the room were the members of the Court Martial - Officers like myself - comrades before whom I was at last to be able to make plain my innocence. Behind them against the wall stood the substitute judges and Commandant Picquart, who represented the Minister of War. M. Lepine, Prefect of Police, was there also. And facing the judges on the opposite side of the room from me sat Commandant Brisset, Judge Advocate, and the clerk, Vallecalle. After taking a seat in front of my counsel, Maitre Demange, I looked at my judges. They were impressive.

Maitre Demange's fight to obtain from the Court a public hearing, the violent interruptions of the President of the Court Martial, the clearing of the court-room, - all these first incidents of the trial never turned my mind from the sole aim to which it was directed. I wanted to be brought face to face with my accusers. I was on fire with impatience to defend my honor and destroy the wretched arguments of an infamous accusation.

I heard the false and hateful testimony of Commandant du Paty de Clam and the lies of Commandant Henry in regard to the conversation we had on the way from the Ministry of War to the Cherche-Midi Prison on the day of my arrest. I energetically, though calmly, refuted their accusations. But when the latter re turned a second time to the witness-stand, when he said that he knew from a most honorable personage that an officer of the Second Bureau 1 was a traitor, I arose in indignation and passionately demanded that the person whose language he was quoting should be made to appear in Court. Thereupon, striking his breast with a theatrical gesture, Henry added: "When an officer has such a secret in his head he does not confide it even to his cap." Then, turning to me, "As to the traitor," he said, "There he is!" Notwithstanding my vehement protests, I could obtain no explanation of his words; and consequently I was powerless to show their utter falsity.

I heard the contradictory reports of the handwriting experts, two testifying in my favor and the other two against me, at the same time bearing witness to the numerous points of difference between the handwriting of the bordereau and my own. I attached no importance to the testimony of Bertillon, for his so-called scientific mathematical demonstrations seemed to me the work of a crazy man.

All charges were refuted during these sessions. No motive could be found to explain so abominable a crime.

In the fourth and last session, the Judge Advocate abandoned all minor charges, retaining for the accusation only the bordereau. This document he waved aloft, shouting:-

"Nothing remains but the bordereau, but that is enough. Let the judges take up their magnifying glasses."

Maitre Demange, in his eloquent speech for the defense, refuted the reports of the experts, showed all their contradictions, and ended by asking how it was "possible that such an accusation could have been built up without any motive having been produced."

To me acquittal seemed certain. I was found guilty.

I learned, four and a half years later, that the good faith of the judges had been abused by the testimony of Henry (he who after wards became a forger) as well as by the communication in the court-room of secret documents unknown to the accused and his counsel; documents of which some did not apply to him, while the rest were forgeries.

The secret communication of these documents to the members of the Court Martial in the Council Chamber was ordered by General Mercier.